Introduction

On the eve of World War Two, Great Britain had 12 capital ships and 3 battlecruisers at her disposal. Right after World War One, this number stood at 46. The Washington Treaty, signed in 1921 by the major naval powers at the time in order to prevent a new arms race, stipulated that in the 20s, 28 British warships be dismantled. Four others were converted to aircraft carriers and one was used as a training vessel. The five Queen Elizabeth class vessels and the five of the Royal Sovereign class were retained, just like the battlecruisers HMS Hood, Repulse and Renown (72). HMS Nelson and Rodney were introduced in 1926 as the new capital ships.

Halfway through the 30s though, five new battleships were laid down. This George V class was in the design stage when the fleet treaties expired. These modern vessels could only be commissioned well after the start of World War Two.

In the course of the 30s, the British Admiralty understood that the battleship couldn't always be considered the primary weapon at sea. It turned out more and more that carriers and submarines could be tasked with important offensive actions. The techniques used in these vessels became more and more sophisticated. Moreover, a number of tasks, normally carried out by battleships like coastal bombardments and destruction of enemy surface vessels, could just as well be carried out by the faster and much cheaper heavy cruisers.

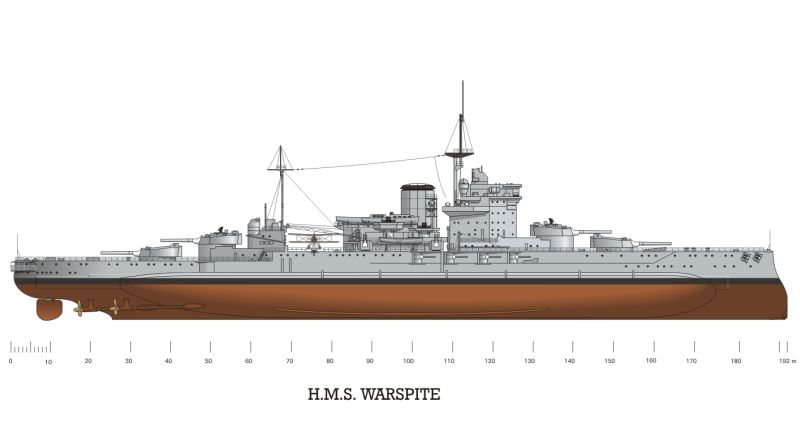

Therefore it was decided to thoroughly upgrade a number of the Queen Elizaberh class vessels instead of laying down more battleships. This class from the First World War had been retained because they were considered the best battleships of their time. With their 38.1cm guns they were more heavily armed than their contemporaries with 34cm guns at their disposal. Furthermore, these vessels were equipped with a good fire direction system, which made their 38.1cm artillery that much more accurate. Finally, they were equipped with oil-fueled boilers instead of boilers partially or even entirely fueled with coal. This not only increased the speed of the vessel - up to 24 knots - but they were also cleaner and more spacious which was very much appreciated by the crews.

The class consisted of HMS Queen Elixabeth, Warspite, Valiant, Malaya and HMS Barham. The Malaya was paid for by the Malayan Federation and therefore named after this country of the British Commonwealth. Actually, a sixth vessels of this class had been ordered which would be named Agincourt but the order was annulled for budgetary reasons.

The entire class was upgraded during the 20s and 30s. HMS Warspite was the first vessel of this class which was fully adapted from 1934 onwards to the modern requirements. HMS Queen Elizabeth and Valiant were being thoroughly upgraded from 1937 onwards. The latter vessel was completed just in time to take part in the first stage of the war. Adaptations of HMS Queen Elizabeth lasted until the end of 1940. HMS Barham and Malaya have never been upgraded in this way.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Commonwealth

- Intergovernmental organisation of independent states in the former British Empire. A bomber crew could include an English pilot, a Welsh navigator, air gunners from Australia or New Zealand. There were also non-commonwealth Poles and Czechs in Bomber Command.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Vessels in this class

Overview of class

| HMS Queen Elizabeth | HMS Warspite | HMS Valiant | HMS Barham | HMS Malaya | |

| Ordered: | June 1912 | June 1912 | June 1912 | June 1912 | 1913 |

| Laid down: | October 21, 1912 | October 31,1912 | January 31, 1913 | February 24, 1913 | October 20, 1913 |

| Built by: | Devonport Royal Dockyard Plymouth | Devonport Royal Dockyard Plymouth | Fairfield, Govan Glasgow | John Brown & Company, Clydebank | Armstrong Whithworth & CO Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne |

| Launched: | October 16, 1913 | November 26, 1913 | November 4, 1914 | December 31, 1914 | March 18, 1915 |

| Commissioned: | December 22, 1914 | March 8, 1915 | February 19, 1916 | October 19, 1915 | 1 February 1, 1916 |

| Number | 00 | 03 | 02 | 04 | 01 |

| First upgrade: | 1926-1927 | 1924-1926 | 1929-1930 | 1930-1933 | 1934-1936 |

| Second upgrade: | 1937-1940 | 1934-1937 | 1937-1939 | - | - |

| End | Dismantled in 1948 | Dismantled between 1947 and 1956 | Dismantled in 1948 | Sunk by three torpedo hits, November 25, 1941 | Dismantled in 1948 |

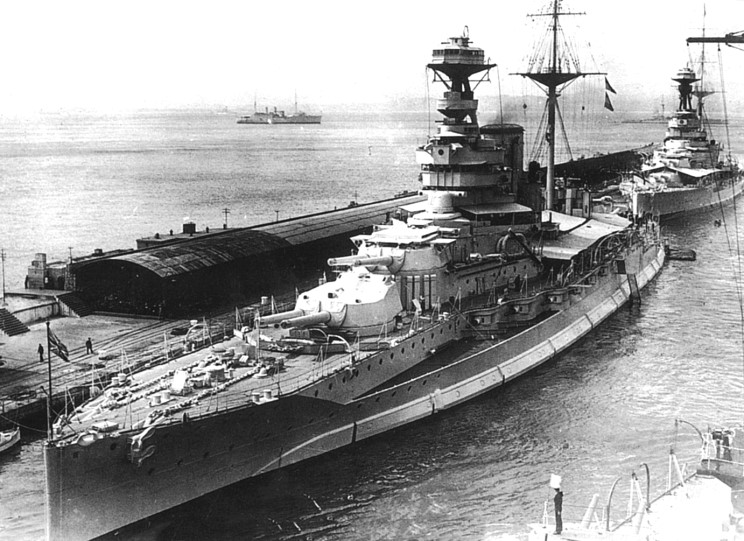

HMS Barham in final assembly at John Brown & Company, Clydebank, Scotland in 1915. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock

Technical data at completion

| Length over all: | 646 feet |

| Beam over all: | 90 feet |

| Draught: | 30 feet |

| Displacement standard: | 27,940 BRT |

| Dsiplacement max: | 33,000 BRT |

| Power plant: | 4 Parsons steam turbines |

| Boilers: | 24 Babcock & Wilcox |

| Power output: | 75,000 hp |

| Propellors: | 4 3-bladed, direct drive axles |

| Fuel capacity: | 3,400 tons of fuel oil |

| Maximum speed: | 24 knots |

| Range: | 8,600 nautical miles at 12.5 knots, 3,900 at 21 |

| Crew: | 950 |

| Main armament: | 4 twin Mk I 38.1cm guns |

| Secondary armament: | 14 Mk XII 15cm guns*1 |

| Air defense: | 2 7.6cm AA guns |

| Torpedo tubes: | 4 53.5cm submerged |

| Belt armor: | 13 inch sloping to 6 at bow and stern |

| Turret armor: | 13 inch, command tower 12 |

| Deck armor: | 1 to 3 inch |

Definitielijst

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

HMS Queen Elizabeth

During World War One, HMS Queen Elizabeth participated in the Battle of Gallipoli but she missed the Battle of Jutland because she was in maintenance. The vessel was present at the surrender of the German Hochsee Flotte (Ocean Fleet) in 1918. Aboard the new vessel, the demands for capitulation were handed over to Admiral Von Reuter. From 1919 the function of the vessel alternated between flagship of the Atlantic and of the Mediterranean Fleet.

In 1926 and 1927, the vessel was upgraded for the first time. Both funnels were replaced by one large funnel and the two 7.6cm AA guns were replaced by two longer range 10.2cm pieces. Furthermore, the fire direction system was improved, meaning adaptations to the bridge structure was needed as well. Finally, the aircraft ramp on Y turret was removed. The most important change however was the installation of anti-torpedo hull reinforcements. These so-called torpedo bulges prevented torpedoes from exploding against the flat hull but made them change direction. The disadvantage of these devices was that the maximum speed of the vessel was lowered to 22.5 knots.

After successful trials, the vessel reentered service in 1928 The vessel was then sent back to the Mediterranean where she remained until 1937. That year, she was selected to undergo a major overhaul at the HMS dockyard of Portsmouth which began on August 11.

The existing 24 boilers were replaced by 8 high pressure versions, leading to a 50% decrease in weight and a 33% increase of space. By replacing the 4 steam turbines as well by newer, improved versions, her maximum speed increased to 24 knots again, notwithstanding the torpedo bulges and the additional deck armor. Another, very important improvement was the changing the elevation angle of the 38.1cm guns. This grew from a maximum of 20 to 30 degrees, increasing the range of the guns to 20 miles as compared to the former 15 miles. The 10.2cm AA battery was expanded with 5 twin emplacements sacrificing part of the 15cm secondary armament.

The AA battery was extended further with a four-barrel 40mm gun, the so-called pom-pom. A hangar accommodating four Fairey Swordfish seaplanes was installed as well, along with the corresponding devices for launching and recovery. In 1939, permission was granted to equip the old vessel with radar in order to improve the fire direction systems. This also meant the entire bridge structure had to be adapted. The vessel was equipped with a type 273 and a 284 Surface Warning (SW) and two type 291 Air Warning (AW) radar units.

In 1940, the upgrading of HMS Queen Elizabeth was not yet completed but because of the regular air raids over southern England, the vessel had to be relocated to HMS dockyard of Rosyth near Edinburgh, Scotland. In December that year, all work was done and trial runs could begin. The vessel was commissioned by Captain C.B. Barry.

Trial runs and training period lasted until March 1941 and thereafter, the modernized vessel was dispatched to the Mediterranean. Here, she was mainly involved in escorting convoys and coastal bombardments in support of British actions in North-Africa.

On December 18, 1941, HMS Queen Elizabeth was berthed in Alexandria, Egypt, where Italian divers managed to place explosives on her and her sister ship HMS Valiant. Both vessels settled on the bottom of the shallow harbor. The attack claimed nine dead aboard the Queen and considerable damage was inflicted.

The vessel was taken into dry dock in Alexandria for emergency repairs. On June 27, 1942, most of the urgent repairs were completed and she was prepared to cross the ocean. An agreement was reached with the US Department of the Navy to have definite repairs made in Norfolk Virginia. One day later, the damaged battleship departed and set sail by way of Durban and Cape Town, South-Africa and Freetown, Sierra Leone to the east coast of the US where she arrived on September 6.

As late as June 1943, reparation had proceeded to such an extent that the battlecruiser, commanded by Captain H.G. Norman could make trial runs again. During this period, preparations had been made enabling new British radar to be installed and the AA battery had been expanded. July 9, the vessel arrived in Devonport, southern England where the radar equipment was installed. In August, she joined the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow in order to test the new systems.

Early January 1944, HMS Queen Elizabeth and other British warships set sail for the Indian Ocean. By way of the Suez Canal, the fleet arrived in Trincomalee, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), on January 28 where the vessels were assigned to the Eastern Fleet. Here, exercises were held during the next months to prepare the fleet for war. HMS Queen Elizabeth became the flagship of the fleet which included her sistership HMS Valiant, the French battlecruiser Richelieu, the Dutch cruiser Hr. Ms. Tromp and the destroyers Hr. Ms. Van Galen (2) and Tjerk Hiddes.

The Eastern Fleet shelled Japanese targets in Sabang on north Sumatra and Burma (now Myanmar). Early 1945 the artillery of the fleet supported the invasion of Burma. Later that year, Sabang was shelled once more and preliminary bombing of the Nicobar Islands was carried out. In July, HMS Queen Elizabeth was relieved by the battlecruiser HMS Nelson and returned to Great Britain where she arrived on August 15.

After the victory over Japan, the vessel was assigned to the Home Fleet once more. In February 1946, the new battlecruiser HMS Howe took over. The Queen Elizabeth was given the reserve status and remained in Portsmouth with a skeleton crew on board.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

HMS Warspite

HMS Warspite did participate in the Battle of Jutland on May 31 and June 1, 1916 and got severely damaged by direct hits of 15 enemy shells. As her rudder was jammed, she could do nothing else but sail in circles and she would have been destroyed by German guns if other British warships hadn't come to her assistance. They drove the German attackers away so she could escape to Rosyth near Edinburgh, Scotland where she could be repaired. During the battle, 14 crew members were killed. On August 24 the same year, she was damaged again after a collision with her sistership HMS Valiant.

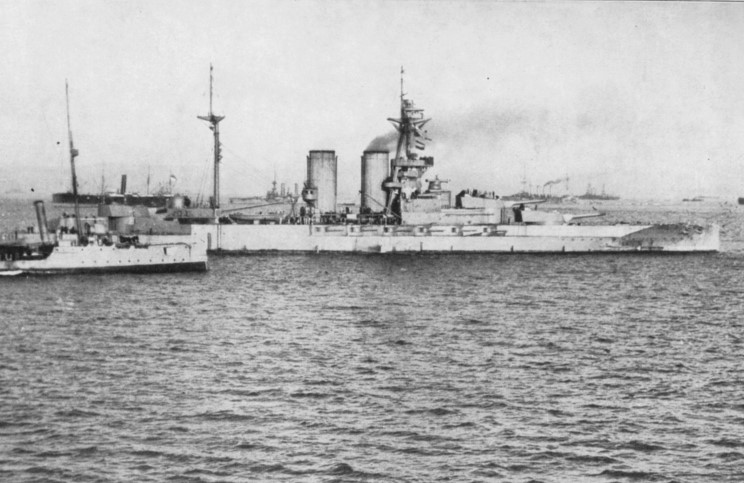

From 1924 until the end of 1926, she was the first vessel of her class to be upgraded. She was the first to be fitted with the torpedo bulges, albeit an experimental version which could be improved later on. The funnels were replaced by two exhausts ending in one large pipe so more deck space was freed which would be filled with low caliber deck guns. After the refit, she became the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet. From 1930 to 1934, she was part of the Atlantic Fleet.

Starting in 1934, HMS Warspite underwent her second upgrade in Portsmouth which was very drastic and would last three years. Her entire superstructure was removed and replaced by a structure taken from the design of HMS Rodney and Nelson. This structure and the construction of the bridge enabled the new fire control systems of the primary, secondary and AA battery to be installed. The new Low and High Angle Director control towers were installed above the bridge. In the last stage of the upgrading, the vessel was equipped with type 285, 286, 271 and 284 radar units connected to the various fire direction systems.

The adaptations to her power plant, deck armor, aircraft and armament were comparable to the later upgrade of her sistership, HMS Queen Elizabeth. After having been put back in service by her commander, Captain V.A.C. Crutchley, she was made flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet once more.

After Great Britain had declared war on Nazi-Germany, HMS Warspite was called back to the Home Fleet to take an active part in hunting down German surface vessels. Over a period of six months though, she never spotted a single large German warship. As late as April 9, 1940, she became actively involved in the war when the Germans invaded Norway. As Sweden was neutral, the invasion had to be launched from the sea. The Royal Navy attempted to prevent this and landed troops on the territory of this Scandinavian country. Meanwhile, Captain D.B Fisher had relieved Captain Crutchley as commander of the vessel.

The British ground forces couldn't prevent the German invasion of Norway though but Churchill's warships did inflict considerable damage to the Kriegsmarine. One of the most important British victories was the Battle of Narvik where HMS Warspite and nine destroyers sank no less than six enemy transports, ten destroyers and a U-boat which had been trapped in Otofjord.

Following this success, the vessel again became the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet, commanded by Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham. On April 17, Captain D.B. Fisher took over command of the battlecruiser. In connection with Operation Catapult, (July 3 to 8, 1940) Admiral Cunningham chaired the successful negotiations about the neutralization of the French fleet in Alexandria. After the capitulation of France, Winston Churchill was afraid that the French warships would fall into German hands and the fleet would either surrender to the British or be destroyed. Aboard HMS Warspite Admiral Cunningham was able to persuade his French opponent, Amiral René-Emile Godfroy to surrender his vessels.

Since the French surrender, Italy had joined the battle and the Royal Navy was faced with another formidable enemy. Escorting convoys to and from Gibraltar, Malta and Alexandria became highest priority for the navy in the Mediterranean. The Italians however were afraid to enter into a direct confrontation with the British who always attacked immediately and were never afraid of losses. The more or less coincidental clashes between capital Italian and British surface vessels usually ended therefore to the advantage of the latter

On July, 1940, an Italian fleet, consisting of the battleships Giulio Caesare, Conte di Cavour and 16 cruisers set sail to escort a convoy to Libya. Admiral Cunningham took the opportunity and attacked the Italians. During an artillery exchange between HMS Warspite and both Italian battleships, the Caesare received the only hit of the skirmish. The hit from the Warspite claimed 115 Italian dead and damage was so severe, the Italian vessel could steam at no more than just 18 knots. The Italians aborted the fight immediately but the British did not dare pursue them as they were afraid of running into a trap set by submarines or land based aircraft.

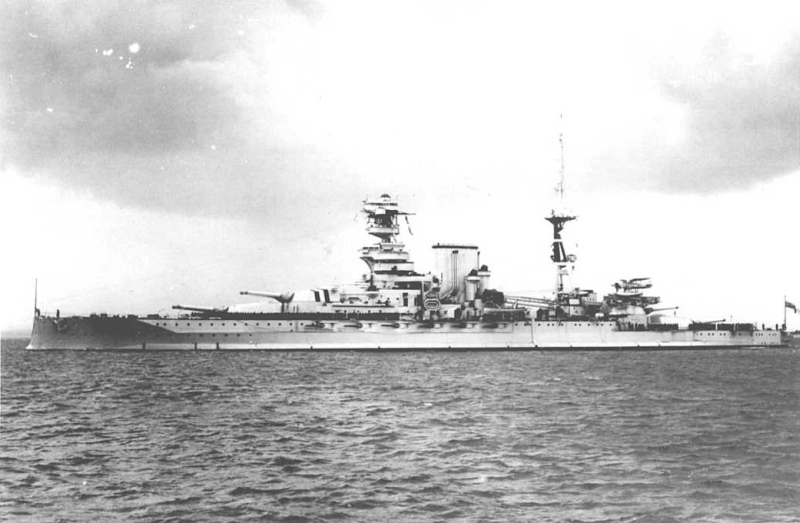

HMS Warspite, after the second overhaul, enters Valetta harbor, Malta. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock

During the Battle of Cape Matapan on March 28, 1941, Warspite and her sisterships HMS Valiant and Barham managed to sink three Italian heavy cruisers and two destroyers.

During the defense of Crete against the German invasion of the last Greek bulwark, HMS Warspite was struck by an enemy 500lbs bomb. The inflicted damage couldn't be repaired in Alexandria and the battlecruiser left for the Bremerton Naval Yard, Seattle where she was repaired and refitted. This lasted until December 28 after which the vessel was put back in service. By way of Sydney, Australia, the vessel steamed to Trincomalee, Ceylon. On arrival, she became the flagship of the Eastern Fleet commanded by Admiral Sir James Sommerville. She also welcomed a new commander, Captain F.E.P. Hutton. She remained in the Indian Ocean for no less than 11 months and returned to Great Britain in Mach 1943. Two months previously, Captain H.A. Packer had taken over from commander Hutton.

In this stage of the war, battlecruisers were not seen any more as the most important units within a battle fleet. This role had been taken over by carriers and submarines. Battlecruisers such as HMS Warspite could for instance still be deployed as convoy escorts but especially as gun platforms in support of amphibious landings. In July 1943, HMS Warspite and her sistership HMS Valiant were deployed in support of the invasion of Sicily and in September, they shelled enemy strongpoints during the Allied landings near Salerno. September 9, they escorted Italian warships to Malta after Italy had surrendered and had defected to the Allied side.

HMS Warspite firing at German positions in Normandy, June 1944 (X-turret shut down). Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocockh

September 16, HMS Warspite was struck by a German FX 1400 armor piercing bomb. This weapon, dropped by the new, very fast and high-flying Dornier Do 217 bomber, had a very destructive effect on the old battlecruiser; she was hit in the boiler room and came to a dead stop immediately. Moreover, the entire fire direction was cut off and the aft X turret was damaged. A small armada of tugs towed the severely damaged vessel to Malta and later on to Gibraltar where emergency repairs were carried out. The crippled vessel arrived in Rosyth, Scotland as part of a convoy. It was considered unprofitable to make full repairs to the cruiser and it was considered sufficient to partially fix the boilers, enabling the vessel to steam at just under 21 knots. Damage to the X turret wasn't repaired. Captain M.H.A. Kelsey had been named her new commander on March 17.

The old vessel was still very useful to be part of the Allied fleet that carried out preliminary shelling of the Normandy coast on D-Day. Even after June 6, she saw action with her remaining six 38.1cm guns to lend artillery support to the Allied landings by shelling German positions. The vessel would play the same role near Brest where American troops were being held up, near Le Havre in September and near the Dutch island of Walcheren in November. After she had fired her last shell at the island, the war was over for HMS Warspite. She returned to England and berthed in Portsmouth where the old cruiser was mothballed on February 1, 1945 after more than 30 years of service.

Definitielijst

- caliber

- The inner diameter of the barrel of a gun, measured at the muzzle. The length of the barrel is often indicated by the number of calibers. This means the barrel of the 15/24 cannon is 24 by 15 cm long.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

HMS Valiant

During the First World War, HMS Valiant did participate in the Battle of Jutland. Contrary to her three sisterships also taking part, she didn't receive a single hit. The only damage worth speaking of that she suffered during this war was the result of a collision with her sistership HMS Warspite.

She was upgraded for the first time between 1929 until the end of 1930. This vessel was also equipped with a single funnel and anti-torpedo hull reinforcements. The aircraft ramps on B and Y turret were replaced by a single catapult. Furthermore, a 40mm eight-barrel AA gun, a so-called pom-pom was fitted. Due to the alterations, her maximum speed was reduced to some 21 knots.

In 1937, a second upgrade was started in Devonport near Plymouth. Her powerplant was adapted in the same way as her sistership, HMS Queen Elizabeth, raising her maximum speed to 24 knots. Her main armament was likewise upgraded. In contrast to her sistership the Queen, her entire secondary battery of 15cm guns was replaced by 10 twin emplacements of 10.2 AA guns. The AA battery itself was expanded with another three eight-barrel 40mm pom-poms. These weapons were grouped around the funnel. She also was equipped with radar equipment (same as HMS Queen Elizabeth) connected to the various fire direction systems so the entire bridge structure had to be adapted drastically.

Modernization lasted until November 1939 and after that trial runs and training period could begin. As from August 26 that year, Captain Sir H.B. Rawlings was appointed commander of the battleship. In February 1940, HMS Valiant was assigned to the Home Fleet; initially deployed as convoy escort and later on tasked with hunting down German surface raiders. In April and May, she joined in the fighting against the Germans occupying Norway. The British scored a few victories off the coast and in the fjords but couldn't prevent the strategically important Scandinavian country from being occupied.

On June 15, HMS Valiant was assigned to Force H, commanded by Admiral Sommerville in the Mediterranean. On July 30, 1940, the cruiser played a main role, together with HMS Hood and Resolution in the attack on the French fleet in Mers-el-Kebir in Algeria. In connection with Operation Catapult, a number of French warships in this French colony were severely damaged as Winston Churchill was afraid these vessels would fall into German hands after France had capitulated on June 22. During the rest of the year and the first months of the next, she mainly protected convoys. On October 30, 1940, Captain C.H. Morgan was named commander of the vessel.

On April 20, 1941, the Libyan capital and port of Tripoli were heavily shelled by HMS Valiant and her sisterships HMS Warspite and Barham, protected by the other vessels of Force H and another Mediterranean Fleet, Force C. Libya was an Italian protectorate and the Italians used Tripoli as transit port to supply their forces in North-Africa. That day, severe damage was inflicted on the harbor facilities and the supply was blocked for months.

On November 25, 1941, her crew was witness to the sinking of their sistership HMS Barham. The unfortunate vessel was struck by three torpedoes, launched from close range by U-331. There was a camera operator aboard HMS Valiant who recorded the dramatic event on film.

At the same moment as HMS Queen Elizabeth the Valiant fell victim to Italian divers who attached explosives to both vessels lying at anchor in Alexandria, Egypt, on December 18, 1941. Damage to HMS Valiant wasn't as extensive as to her sistership but it took over three months nonetheless before repairs had progressed to such an extent that the vessel could set sail to Durban, South-Africa for final repairs. Furthermore, the vessel received a new commander in the person of Captain L.H. Ashmore. In July, the vessel could start her trial runs and afterwards she saw action in the Pacific for six months before being called back to Devonport, southern England for maintenance. During this period, the fire direction radar for the 38.1cm guns was replaced and a number of 20mm Oerlikon AA machineguns were also fitted.

During the Allied landings on Sicily of July 1943, she provided cover from off shore by shelling German positions. She was given the same task in August and September during the Allied landings on the Italian mainland. On September 9, she and HMS Warspite escorted Italian warships to Malta after Italy had surrendered to the Allies. On October 15, Captain G.E.M. O'Donnell took over command from Captain Ashmore.

In 1944, the vessel was dispatched to the Pacific to join the Eastern Fleet, taking part in the shelling of Japanese targets in Sabang on Sumatra. On August 8, she was severely damaged in Trincomalee, Ceylon when the dry dock in which she had been taken, collapsed. Her two inner propellors and her rudder were blocked. As the vessel had already gained steam (the dock was being filled with seawater to enable the vessel to leave it), she escaped further damage. It was decided to send the vessel to the necessary dock facilities in Alexandria in order to repair the sustained damage. The crippled vessel could no longer hold course and therefore couldn't cover more than 8 miles an hour. She did reach the southern entrance of the Suez Canal due but due to her condition, she couldn't pass through it. Hence she was forced to sail around Africa. By way of Durban and Cape Town, South-Africa and Freetown, Sierra Leone the crippled vessel dropped anchor in Plymouth, southern England on February 2, 1945.

Reparations to HMS Valiant took over 18 months and as from August 1946, the vessel, renamed HMS Imperieuse was used as a training ship for engineers in Devonport, Plymouth.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- surface raiders

- Heavily armed and fast merchant vessels, mostly used by the Germans in the early years of both World Wars.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

HMS Barham

Just like her sisterships HMS Warspite, Valiant and Malaya this vessel was involved in the Battle of Jutland. During this fight, she fired 337 shells and suffered five enemy hits that caused little damage though. In the 20s, both funnels were replaced by a single one with two exhausts and torpedo bulges were fitted just like her sisterships.

In the interbellum, she was upgraded only once. This period lasted from 1930 to 1933 and mainly entailed an expansion of her armament. Next to the funnel, two eight-barrel 40mm pom-poms were fitted and eight .50 machineguns were mounted near the forward control tower. The bollard masts were replaced by tripod masts to accommodate both High Angle Director control towers. During the war, another two eight-barrel 40mm pom-poms were fitted.

In September 1939, she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet commanded by Captain Sir H.T.C. Walker and mainly served as convoy escort. In December, she was called back to the Home Fleet in order to protect convoys in British waters. On December 12, during one of these voyages, a serious accident occurred. Nine miles west of Mull of Kintyre, between Scotland and the northeastern tip of Ireland, the vessel collided with the destroyer HMS Duchess. Due to the impact, the destroyer capsized and sank, claiming the lives of 124 out of the 147 crew members.

Two weeks later, while on patrol with the battlecruiser HMS Repulse and a number of destroyers, the vessel was struck by a torpedo from the U-30. Damage was extensive and four men lost their lives, Despite the list to port, she was able to reach Liverpool harbor on her own power where she was taken into Gladstone Dock to be repaired. This would take six months.

In September 1940, she participated in Operation Menace. The goal was to capture the port of Dakar, Senegal from the Vichy-French and hand it over to the Free French fighting on Allied side and commanded by Genéral Charles de Gaulle. The Allied fleet consisted of the battleships HMS Barham and HMS Resolution, the carrier HMS Ark Royal and some 13 cruisers and destroyers. The Vichy-French had the modern battleship Richelieu at their disposal and a number of cruisers and submarines. Their main defense however were the heavy coastal batteries on Cap Manuel and Ile de Gorée.

On September 24, Genéral De Gaulle executed a landing with 2,400 men of the Free French supported by 4,270 British soldiers, hoping his fellow countrymen would receive him and defect to the Allied side. When he and his troops were fired at, he had the French troops break off the attack as he didn't want French blood to be shed by French. The British vessels however returned the Vichy fire and an artillery duel erupted which would last two days with interruptions. On September 25, two Vichy-French submarines sneaked out of the harbor and one of them successfully torpedoed HMS Resolution that was put out of action listing heavily to port. HMS Barham was struck at her bow by a 38cm shell from Richelieu that caused no fatal damage though. Two British cruisers were damaged as well by fire from Richelieu and the coastal batteries after which the attack was aborted. The Barham towed Resolution to Freetown, Sierra Leone for emergency repairs and she left for Gibraltar herself for repairs. Dakar remained in Vichy hands until the French commander of the Marine National, Amiral Darlan was forced to go over to the Allied side in 1942.

From early 1941 on, she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet again. On March 25, Captain G.C. Cooke had taken over command of the old vessel. Three days later, HMS Barham participated in the Battle of Cape Matapan. April 20, he vessel took part in the shelling of Tripoli harbor. Churchill actually wanted to HMS Barham and an old cruiser to be sunk to block the Libyan capital but Admiral Cunningham didn't want to sacrifice the vessel and after consultation, it was decided to a shell the city from the sea instead.

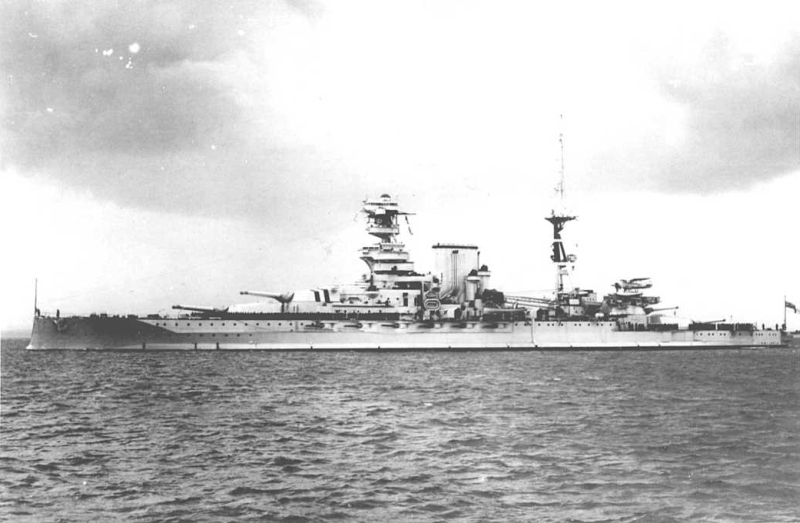

HMS Barham struck by three torpedoes from U-331, November 25, 1941. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock

On November 25, 1941, she was on her way to cover a British attack on an Italian convoy. At 16:29, from a range of just 900 yards, the battlecruiser was struck by three torpedoes from U-331. They hit the vessel simultaneously below X turret on her port side close together below the waterline so only one water column was observed. This made the vessel take in water so fast that only a few of her crew were able to leave the vessel. After she had tipped over to 90 degrees, she exploded and sank within four minutes. 862 crew members went down with her including the commander and 449 men were rescued.

On the vessel closest to the scene, HMS Valiant, a camera operator of Gaumont News, John Turner, recorded the sinking of HMS Barham on film lasting two minutes. The were the most important live images of a sinking vessel during World War Two and later on, the recording was used in various feature films.

The commander of U-331, Hans Dietrich von Tiesenhausen, who remained submerged after having launched his torpedoes, slipped away and wasn't aware of his success. The British Admiralty didn't notice any German message pertaining to HMS Barham having been sunk by a U-boat and decided to withhold the news so as to fool the Germans and to keep British morale high. A few weeks after the disaster, the next of kin were told the news but with the firm request to not talk about it with anyone. As late as January 27, 1942, after the Germans knew about it, the sinking of HMS Barham was officially announced.

Von Tiesenhausen was awarded the Iron Cross for his contribution to the sinking of the British vessel. How he managed to penetrate the screen of destroyers, get so close to the warship and get away unnoticed, the Royal Navy never found out. An investigation by the British navy revealed however that the explosion aboard HMS Barham had been caused by AA ordinance which had been stored in places unsuitable for this purpose. In that phase of the war, British warships carried so much ammunition of that type that shells were stored in any odd possible place. As a result of this investigation, based on recordings, wreckage and theories, British war vessels were prohibited to carry more ammunition than could be stored in the magazines.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- Iron Cross

- English translation of the German decoration Eisernes Kreuz.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

HMS Malaya

During the Battle of Jutland, HMS Malaya suffered no less than eight hits claiming 65 dead. Damage to the vessel was extensive and was repaired on the yard which had delivered her over a year ago, Armstrong-Whitworth of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The single funnel and torpedo bulges were fitted just like her sistership in the 20s.

From 1934 until the end of 1937, she underwent her only drastic upgrade. A hangar, cranes and a catapult were fitted to launch and recover Fairey Swordfish seaplanes. Two eight-barrel 40mm pom-poms were fitted next to the funnel. The foremast was reinforced so two High Angle Control (HAC) towers could be fitted. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, fire direction of her main armament as well as the AA battery were expanded with a type 286 Air Warning and a type 284 Surface Warning radar on the Low Angle Control tower. Moreover, two type 285 radar devices were installed on the HAC control tower. The AA battery was expanded with a number of 20mm Oerlikon machineguns.

From the beginning of the Second World War she served, commanded by Captain I.B.B. Tower, mainly as part of the Mediterranean Fleet, escorting convoys. From early 1940 on, these operations were switched to the Atlantic. May 20 of that year, Captain Sir A.F.E. Palliser took command of the vessel and led her back to the Mediterranean Fleet commanded by Admiral Cunningham at the time when the latter opened negotiations with French admiral Godfroy during Operation Catapult.

As her powerplant hadn't been upgraded, she lacked speed and range. Therefore the vessel was hardly deployed on important missions but mainly as a convoy escort. That even these tasks were not without danger, was proved on March 1941 when she was hit by a torpedo from U-106, some 250 miles northwest of the Cape Verde islands. Damage was considerable and a few compartments had been flooded. Listing seven degrees to port, she reached the safe harbor of Pot of Spain, Trinidad. After emergence repairs had been carried out on the Caribbean island, she left for New York, arriving at the Brooklyn Naval Yard on April 6 for final repairs.

On May 3, 1941, Captain Palliser was replaced by Captain C. Coppinger and in July the vessel resumed her duties as convoy escort, protecting an important troop transport from Nova Scotia to Glasgow, Scotland. A few months later, she became flagship of Force H of the Mediterranean Fleet. Admiral Sir James Sommerville wasn't very much impressed by the old battleship but he had to make do with what he had at the time.

In November and December she underwent a drastic upgrade in Rosyth, Scotland. During this period, the aircraft facilities were removed and a number of 20mm Oerlikons was added. Since May of that year, Captain J.W.A. Waller was in command of the vessel. After a short period of training, she was deployed again as convoy escort but now as part of the Home Fleet in the Atlantic.

Six months later in August 1943, the vessel was laid up in Faslane on the Clyde near Glasgow and put in reserve as her powerplant caused too many technical problems. This period was interrupted by a short period, during September and October 1944 when the vessel was deployed to bomb the Brittany coast. In May 1945 the vessel was renamed HMS Vernon II, stripped of her entire armament and deployed as accommodation and training vessel of the Torpedo School in Portsmouth.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Epilogue

Right after the Second World War, it soon became clear that the remaining four Queen Elizabeth class battleships could no longer be retained by the Royal Navy. The old vessels no longer matched the modern requirements and were far too expensive as to maintenance. The tasks as training ships, assigned to the four veterans of both world wars, was taken over by the four remaining King George V class vessels.

HMS Warspite had gained great fame with her excellent service record during World War Two. Out of all British warships, she had been awarded the highest number of Battle Honors. The British population felt close ties to the old vessel and wanted very much to preserve her as a museum vessel. Yet it was exactly HMS Warspite, the first vessel of the Queen Elizabeth class that was sold for scrap to Metal Industries of Faslane. The old lady didn't surrender without a fight though.

In March 1947, The discarded battleship left Portsmouth, towed by a number of tugs on her way to her destination, the river Clyde. In a heavy storm, the towing cables snapped and she ran aground in Prussia Cove, a small inlet in Mount's Bay, southwestern Cornwall. The heavy wreck couldn't be towed off so her entire superstructure and deck were removed on site which took until 1950. Subsequently, the hull was towed free and she was beached on Marazion Beach near St. Michael's Mount where she was demolished. As Mount's Bay is in a rather remote location, it took almost seven years before the last remaining parts of the once mighty vessel had been demolished and taken away.

The three remaining Queen Elizabeth class battleships were sold for scrap in 1948. The former Queen Elizabeth and Valiant arrived at the demolition yard of Arnott Young in Cairnyan on July 7 and August 11 respectively. The former Malaya arrived at Metal Industries in Faslane on April 12.

Despite the excellent reputation of HMS Warspite and to a somewhat lesser extent of HMS Valiant and Queen Elizabeth, the battleships of this class were forced to play a secondary role. The purpose for which the vessels had been designed and constructed had been overtaken since the First World War and despite their upgrading, they still were slower and had a shorter range as compared to modern warships. The main problem though was the vulnerability of the old vessels which resulted in the long periods of repairs of all vessels but especially in the sinking of HMS Barham

Yet, the battlecruisers have earned their offensive value as artillery platforms during the numerous coastal bombardments and shellings of ports and facilities. The defensive power of the old vessels was proven throughout the war by the many convoys that were being protected by these vessels and others. Their presence was usually impressive enough to keep enemy vessels at bay. Despite all shortcomings and failures, the Queen Elizabeth battlecruisers have made an important contribution to the Allied victory.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!