Introduction

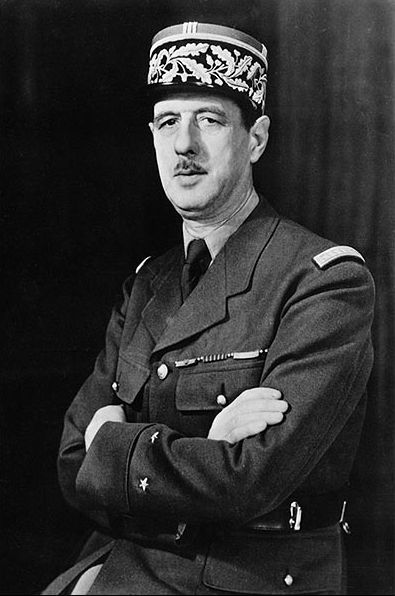

He was one of the few French military who was not discouraged by the capitulation of France. Initially, he and just a few followers decided to continue the struggle from England. Later on he received more and more support; as the leader of the Free French he managed to free the colonial empire from the Vichy regime and he made France one of the larger Allied powers.

After World War Two, he was elected President of France and he just managed to prevent civil war from breaking out. Numerous attempts on his life were made but he died of natural causes in 1970. The French population named him the greatest Frenchman of all time. His name: Charles de Gaulle.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

Images

Prior to World War Two

Childhood years

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was born 22 November 1890 in the industrial town of Lille in northern France. He was the third child of Henri de Gaulle and his wife Jeanne Maillo. His father taught classical languages at a Jesuit college. His parents were Catholic. He grew up in a right-wing conservative environment. He attended the primary school run by the monks. He received his secondary schooling from the Jesuits. He also attended Stanislas College in Paris after his parents had moved to that city in 1901.

Charles de Gaulle read a lot and possessed a good memory. Writing was embedded in the genes of the De Gaulle family. This also applied to young Charles who wrote poems and a few plays. He was a great admirer of authors such as Charles Maurras and Maurice Barrès. The works of these nationalistic writers were typified by a militaristc undertone and strong feelings of revenge against Germany which had scored a crushing victory over France in 1871. De Gaulle would be strongly influenced by these writers. Maurras in particular was also known for his anti-Semitism; he supported the idea that all alien elements, Jews, Protestants and Free Masons be removed from French society. His biographers agree that Charles did not share these notions. De Gaulle did agree however with other ideas of these writers. In his own books, he would frequently refer to them by using quotes.

At an early age, De Gaulle dreamt of a brilliant military career. At the age of 18, he wrote: "If I am to die, let it be on the battlefield.". On 7 October 1909, De Gaulle entered military service. On 6 April 1910, he was promoted to Caporal (corporal) and on 27 September to Sergeant. On 14 October 1910, he was admitted to the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint Cyr (Special military school), a military academy for future officers. He was a fine and devoted pupil. He ended his final year as 13th out of 210 students. After graduation, he was posted to the 33ième Regiment d’Infanterie de Ligne (33rd Infantry Regiment) commanded by Philippe Pétain (whose name will appear more often in this article). 1 October 1913 saw De Gaulle promoted to Lieutenant.

De Gaulle and the First World War

The assassination of the Austrian pretender to the throne Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 by the Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip led to World War One by a system of alliances. France, Russia and Great Britain (the Entente) took on an alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary. De Gaulle would surely have welcomed the First World War. It offered him the chance to expand his military career and revenge on Germany could finally be taken.

The war did not progress for De Gaulle as he had wished however. On 15 August 1914 he sustained a knee injury by a riflebullet. For this, he was treated in Paris and Lyon and returned to the front as late as October 1914. In January 1915, he was mentioned in dispatches for having crossed the no mansland between the front lines and had eavesdropped on discussions in the enemy trenches which yielded extremely useful information. 15 March 1915, he was wounded again, this time an exploding mine caused an injury on his left hand. In June he again returned to the front. Later that year, on 30 October, he was promoted to Capitaine (Captain).

On 2 March 1916, the end of World War One came for De Gaulle however. During the battle for Verdun he led a charge to break up an enemy encirclement. He was wounded in his left buttock by a bajonet and was rendered unconscious by an exploding grenade. When he regained consciousness, he discovered he had been taken prisoner by the Germans. He was to spend the remainder of the war in a prison camp.

De Gaulle was very upset about his imprisonment. Whereas his fellow officers got the chance to earn decorations and be promoted, he was pining away in a prison camp near Ingolstadt. On 12 May 1916, he wrote to his sister: "You will understand my sorrow for having had to leave the battle in this way." De Gaulle made several attempts at escape but was caught each time by the Germans. His conspicuous height of 6 feet 4 was his disadvantage, it made him easily recognizable. De Gaulle would be released from imprisonment after the capitulation of Germany in 1918.

Following this, he fought in the Russo-Polish war (1919-1921). This war broke out when the newly established Polish state attempted to move her border further to the east. The Poles received military support from the French army. De Gaulle was employed as an instructor for the Polish army and later commanded an infantry battalion in action, enabling him to gain some wartime experience. He received a Polish military decoration, the Order Wojenny Virtuti Militare - Kryz Srebrny (Silver Cross of the Order of Miltary Courage). In January 1921, he returned to France. On 18 March 1921, the war ended with the Peace Treaty of Riga. Both parties claimed they had defeated the other (today, the general notion is that the Poles had won the war). At the end of the war, De Gaulle returned to France.

Interbellum

On 7 April 1921, Charles de Gaulle married Yvonne Vendrou (1900-1979). Yvonne came from a wealthy family which possessed, among other things, a biscuitfactory in Calais. Together they would have three children: Philippe (1921) probably named after De Gaulle’s mentor, Philippe Pétain; Elisabeth (1924) and Anne (1928-1948) who was born with the Down syndrome.

During his imprisonment, De Gaulle had already started giving lessons on military strategy and tactics to his fellow prisoners. He discovered he had a gift for it and continued teaching after his return to France. He taught at the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint Cyr. De Gaulle himself attended a course in advanced strategy for senior officiers on the General Staff at the École Superieure de Guerrre. His final marks turned out lower than he had expected though. This was mainly caused by him having had a conflict with the head master of the institution about what strategy should be best followed. His differing view on strategy would get him in trouble more than once.

After the First World War, France embraced a strategy mainly aimed at defence, the best example being the heavily fortified Maginot line. De Gaulle however wanted to pursue an offensive strategy. He dreamt of modern motorized armies that would score quick victories, supported by independent tankregiments and heavy artillery. He also voiced this vison in the books he wrote from 1924 onwards and the lectures he delivered. In France he found little response however and his ideas were considered vague, unattainable and too imaginary. His contradictory view did not do his military career any good either. He only managed to rise with the help of Pétain. On his urging, De Gaulle was posted to his personal staff in 1925. On 25 September 1927, De Gaulle was promoted to Commandant (major). In this capacity, he was part of the force of occupation in the Rhineland from 1927 to 1929 as commander of an infantry battalion. Subsequently he was posted to Beirut for two years which was at that time part of the French mandate of Lebanon. After his return to France in 1931, he became staffofficer at the secretary’s office of the national defence council. He was also introduced to the right-wing politician Paul Reynaud, later on the French Prime Minister.

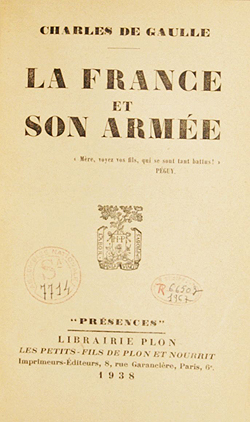

He was promoted to Colonel on 13 July 1937 and appointed commander of the 507ième Regiment de Chars de Combat (tankregiment) in Metz; this unit was part of the 5ième Armée Française (French 5th Army). He enthousiastically set about putting his theories in practice. He had the regiment train so intensively causing the maintenance department to start complaining about the tanks wearing down too much. In this period he also wrote a book on the military history of France. To this end, he used a preliminary study he had made when he was employed on the personal staff of Pétain. Therefore, Pétain took the view he owned the copyright of the book and asked De Gaulle not to publish it. De Gaulle did so nonetheless. The ensuing conflict was the definite split between Charles de Gaulle and Philippe Pétain. It is remarkable that this book, the only pre-war book by De Gaulle, became a success: over 7.000 copies were sold.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Maginot line

- French defence line along the French-German border.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Rhineland

- German-speaking demilitarized area on the right bank of the Rhine which was occupied by Adolf Hitler in 1936 after World War 1.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

France is occupied

The German invasion

Following the German invasion of Poland, Great-Britain and France declared war on the Third Reich on 3 September 1940. The following months, almost nothing happened however. Both parties waited for each other, hence this period was also called the phony war. The French army did not make use of this period to offer the necessary training to its soldiers. Because they had nothing to do, the morale deteriorated rapidly. "

On 20 March 1940, the left-wing government of Édouard Daladier collapsed. Paul Reynaud succeeded him as Prime Minister and Daladier was appointed Minister of War. Reynaud offered De Gaulle the post of state secretary of defense but De Gaulle refused because he did not want to work with Daladier.

On 10 May, Germany went into the offensive. Codenamed Fall Gelb, a co-ordinated attack was launched by the German armed forces against Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg and France. The first attack was launched from the north, this was a diversionary attack however. The real offensive was launched through the Ardennes. French military leadership had not thought it would be possible for large motorised units to advance through the Ardennes because of the dense woods, the mountaineous terrain and the bad roads and it was assumed that massing German troops on the river Meuse west of the Ardennes would take five to seven days at least. The German armoured units advanced quickly through the Ardennes though, assisted by the fact that the French Commander-in-Chief, Maurice Gamelin, did not recognise the danger and refused to send reinforcements into the area. On 13 May tanks led by Generalmajor Erwin Rommel crossed the river Meuse near Dinant and Houx. The same day the tanks of General der Panzertruppen Heinz Guderian did the same near Sedan. The French army was completely overwhelmed and was unable to put up any kind of resistance. The armed forces were severely hindered by poor communication between the troops themselves and headquarters and the lack of equipment and air support. A typical example of progress within the French army was that the artillery in the sector Sedan received orders to limit their fire in order to save ammunition. The idea existed that the actual major German attack would be launched a few days later.

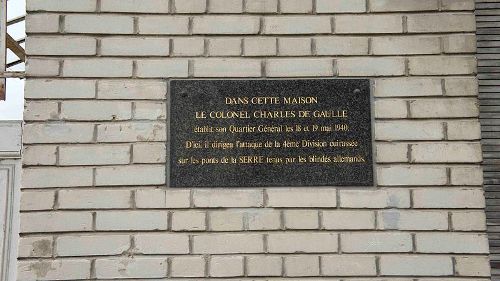

On 11 May De Gaulle was put in charge of the 4ième Division Curassée de reserve (4th reserve armoured division). This division was among the best units of the French army, contrary to what other sources had claimed sometimes. It was equipped with 52 B 1 heavy tanks, 30 D 2 heavy tanks and 39 S 35 Somua medium tanks which were a good match for the German armoured vehicles. The division hardly had any artillery at its disposal though and could call on only a few infantry battalions. Nevertheless Géneral Alphonse George ordered the division to attack. "Carry on, De Gaulle. You, having for so long fostered the ideas the enemy is turning into reality, have the chance to show something." On 17 May, De Gaulle launched a counterattack with his division near Montcornet which was relatively successful. He managed to push back the German infantry temporarily. In the general picture, this action did not amount to much though; it was however one of the few French offensives that were successful. Against stronger opposition and an attack by the Luftwaffe however, de Gaulle was forced to pull back to his starting point.

On 18 May, a change of government took place: Pétain was appointed vice-President and Daladier was fired. On 24 May 1940, De Gaulle was promoted to Général de Brigade (Brigadeer-general) the rank he would retain for the rest of his life. The Germans kept advancing at great speed, on 26 May Boulogne was captured and they stood at the Channell. The Belgian army was forced to surrender on 28 May. Now France lay practically open for the Germans, an attack was launched across almost the entire length of the French frontier (Fall Rot). That day, De Gaulle also launched an attack near Abbéville in order to try and relieve the Allied forces in Dunkirk. This attack too was successful for the time being but had to be aborted due to lack of support from other units.

6 June 1940, De Gaulle was appointed State Secretary of War and National Defense. His main task was to keep in touch with the British government. He asked Great-Britain to deploy the entire R.A.F. to support the French armed forces. Winston Churchill refused though because the Britsh air force was needed to defend the motherland. June 10 he left Paris, being one of the last members of the government; four days later, the city would be captured by the Germans. June 11, negotiations took place between the British and French governments. De Gaulle proposed to evacuate the government to the French colonies in North-Africa and continue the battle from there. For the time being, no attention was paid to this proposal.

June 13, 1940, talks were held again. The French government announced that there was no sense anymore in continuing the battle and an armistice was necessary. De Gaulle was shocked and wanted to resign at first but reversed his decision later. Reynaud wanted to continue the fighting from Algeria. In order to evacuate the French troops, support of the British fleet was needed. To that end, De Gaulle was dispatched to London for talks. On initiative of the French Ambassador in London, Winston Churchill made De Gaulle a counterproposal. This was based on the ideas of Jean Monnet and suggested that Great-Britain and France would merge into one Anglo-French union; this meant having a mutual government and uniting their armies. De Gaulle forwarded this proposal on June 16 by telephone to Reynaud. He presented it to the French cabinet but it was rejected. One of the arguments given was that France was not to become a British dominion. Reynaud subsequently resigned and he was succeeded by Philippe Pétain. The next day (June 17), Pétain asked via the Spanish Ambassador for terms of an armistice. As soon as De Gaulle, who had just returned to France, heard this he drove straight back to the airport and flew back to London in the evening. His suite consisted of an adjutant and one liaison officer. Furthermore he had 100.000 French francs at his disposal. This was the modest start capital of La France Combattante or the Free French.

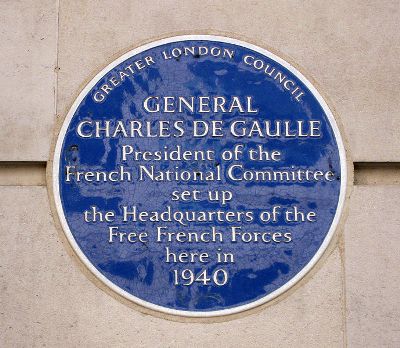

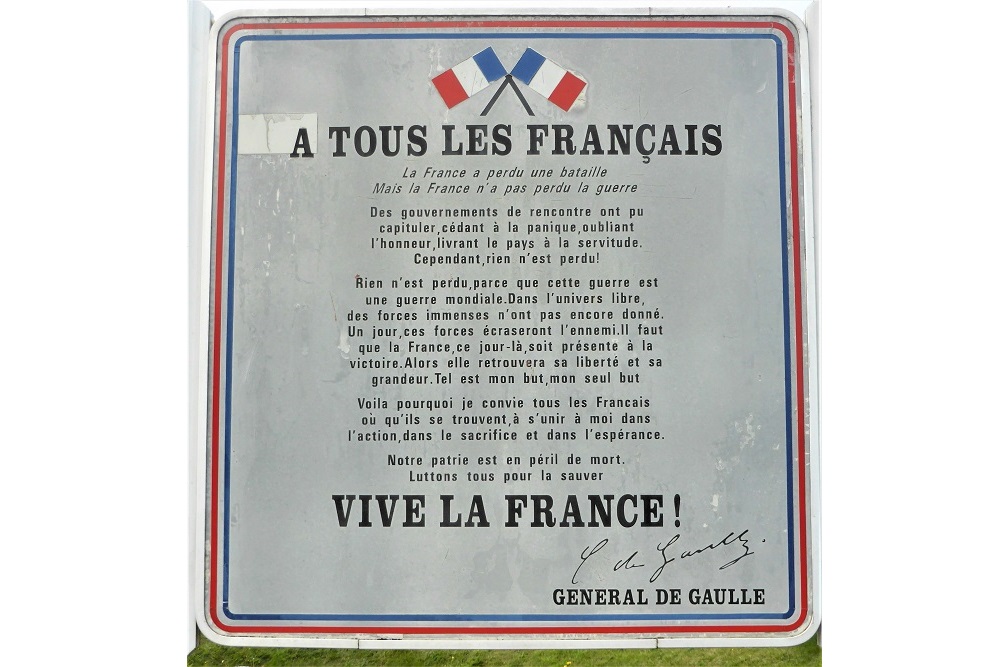

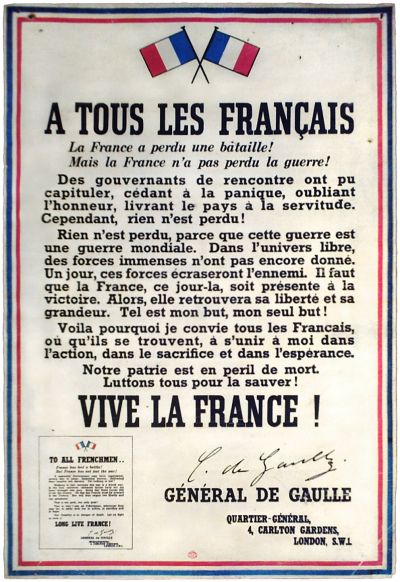

Leader of the Free French

18 June 1940, De Gaulle delivered his first speech by radio to occupied France. (see Speech 18-06). The armisitice was to be effective as from 22 June 1940. In his "Appèl du 18ième Juin" (appeal of June 18) De Gaulle stated that France had been overwhelmed but this defeat was not definite. The struggle could be continued with the support of the British empire. He indicated further that the flame of French resistance should not be extinguished. De Gaulle also announced the establishment of the Free French and he called on French military personnel in England to join him. What impact this speech had is not entirely clear: closer investigation has shown that few French had listenend to it. Moreover, De Gaulle could not yet act as representative of the French population. The democratic governments of the occupied countries which had moved to London, for example the Dutch, could claim that they represented their respective populations. With the De Gaulle this was different because the legitimate government was still located in France. Pétain had formed a government in Vichy that ruled the non-occupied part of France and which collaborated with the Germans.

Hence De Gaulle could not claim he represented the French population. The government even sentenced him in absentia to death later on for desertion and treason. De Gaulle however possesed a boundless self confidence and was highly ambitious. France would and should participate in World War Two again. First however, De Gaulle had to be recognised as the legitimate leader of the French and get himself a territorial base. The Allies recognised De Gaulle as leader of the Free Frech after France had surrendered on June 22, 1940. Churchill recognised De Gaulle on 28 June 1940. More and more people joined De Gaulle, in July 1940, the group numbered some 7.000.

De Gaulle would love to get the French colonies in North-Africa, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, on his side but that was impossible however. The colonial authorities in Algiers were strongly influenced by Vichy-France. Moreover, in French North-Africa, as well as in other French territories, a strong feeling of resentment against the Allies prevailed as they had destroyed the French fleet on July 3, 1940 in Mersh-el-Kébir in Algeria in Operation Catapult in order to prevent the fleet from being captured by the Germans. Besides, De Gaulle rather not wanted to use violence. He hoped to bring these territories under his rule by persuasion. He therefore initially focused on French Equatorial Africa, consisting of French Congo, Chad and Camerun. Chad was the first to join the Free French on 26 August 1940. In the person of Félix Éboué, this territory had a black governor who wanted nothing to do with Hitler’s racial ideas.

Camerun was a former German colony that became a shared French mandate after the First World War. Fear of a return of German rule was so great here that a small group of officers, headed by Jacques-Philippe Leclerc was able to persuade Camerun to quickly join the Free French. French Congo (the present Congo-Brazaville) quickly followed suit. De Gaulle now had territory at his disposal and he could expand his armed forces with military and other persons from the colonies. Strategically, these possesions did not amount to much however. In the conflict with the Axis powers, they were of little value. De Gaulle now focused on French West-Africa, consisting of Senegal, the Ivory Coast and French Sudan (now Mali). French West-Africa was a strategic position. Dakar was of particular importance: the town possessed the best natural harbour in the south Atlantic. If the Axis powers could have that at their disposal, it would have serious consequences for Allied shipping. Therefore the British agreed with De Gaulle it would be better if Dakar came under Free French rule.

An operation was prepared. De Gaulle wanted to prevent the French from fighting each other and he hoped he could have his way by persuasion. On September 23, 1940, an Allied fleet appeared off Dakar, consisting of two battleships, an aircraft carrier and a number of transport vessels with a total of 8.000 soldiers aboard. The Allies hoped the city would surrender, being faced with this kind of military power but that did not happen and skirmishes broke out between the Allied ships and the defenders of the city. De Gaulle had highly overestimated the number of his followers in the city. On September 25, he ordered an end to the fighting as he wanted to avoid more fighting among the French themselves. The operation had failed. The material consequences might have been worse although the British battleship H.M.S. Resolution was severely damaged by the shorebatteries in Dakar harbour and the Vichy-French lost two submarines. Politically however, it was a sharp blow for De Gaulle with the result that West-Africa would remain Vichy-French for a long time to come.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

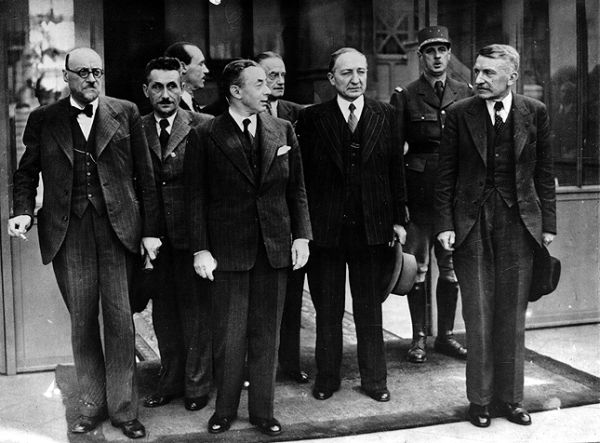

Premier Paul Reynaud and members of his government on 6 Juni 1940. De Gaulle is the man in uniform on the rear right. Source: Assemblée nationale.

Premier Paul Reynaud and members of his government on 6 Juni 1940. De Gaulle is the man in uniform on the rear right. Source: Assemblée nationale. Pamphlet in which De Gaulle announces to the French population that the battle has not yet been abandoned. Source: Assemblée nationale.

Pamphlet in which De Gaulle announces to the French population that the battle has not yet been abandoned. Source: Assemblée nationale.The battle for the French colonies

Conflict with Churchill

Prior to the outbreak of World War Two, France possessed two mandates in the Middle East: Syria and Lebanon. De Gaulle knew the region well as he had been stationed there for two years. He hoped to bring these two countries under Free French rule. Initially he tried this by negotiating but the colonial authorites proved to be unwilling to cut themselves loose from Vichy-France.

On May 2, 1941, in the British mandate of Iraq an armed revolt erupted which was supported by Germany. The Vichy government permitted the Germans to use an Iraqi air base. De Gaulle suddenly had a sound reason to plead for the capture of Syria and her neighbouring country of Lebanon. He now also received military support from the British. The operation was launched on June 8, 1941, 20.000 Allied soldiers, including 7.000 Free French, took up the fight aganst 30.000 Vichy-French. De Gaulle fostered the hope that the Vichy-French would soon surrender. This did not materialise however and heavy fighting ensued, the British were even forced to bring in reinforcements. This time, the offensive was successful; on June 21, 1941, Damascus was captured and on July 14, the British and the Vichy authorities agreed to a cease fire. De Gaulle was kept out of the negotiations and the Vichy-French soldiers were hardly offered any opportunity to join the Free French. Churchill also declared that free elections were to be held in the mandates. De Gaulle was very upset about this and also made it very clear. He made a few anti-British statements. He said for instance that the British did not set up free elections in Egypt either and that there were other more important issues, needing higher priority such as countering the advance of Erwin Rommel in Africa. He also threatened to dissolve the alliance between the Free French and Great-Britain. With these statements, he evoked Churchill’s anger.

The relationship between De Gaulle and Churchill had always been stormy. Early in the war, De Gaulle had said to one of Churchill’s advisors: "You think I consider it important that England wins the war. I do not. I am only interested in the French victory." De Gaulle was characterised by contempories as an unpleasant man: he was cold, aloof, reserved and sometimes rude. When De Gaulle returned to England after the campaign in the Middle East, Churchill gave orders that no one was allowed to meet De Gaulle and that he had to be avoided. Nonetheless, a meeting took place on September 12, 1941 between the two. It began somewhat uneasily but ultimately came to a positive end. De Gaulle apologised for his behaviour and the sky was cleared for the time being.

On September 24, 1941, De Gaulle also estabilshed the Comité National Français (French National Committee or C.N.F.). This committee acted as the French government in exile and possessed legislative powers. It was however not acknowledged as such by all other Allied powers. A few countries, such as the United States would continue to acknowledge the Vichy government as the legitimate French government and they spoke of the C.N.F. as the National Free Committee.

Battle in North-Africa

On 10 June 1940, Italy had declared war on Great-Britain. On August 6, the Italian army had invaded British Somaliland and on September 13 an attack was launched against Egypt. The Italians were pushed back by the British though and they were forced to ask their German ally for assistance. In March 1941, the Deutsches Afrika Korps or D.A.K. commanded by Erwin Rommel arrived in the region. A seesaw battle ensued in which Rommel made great progress, especially in the beginning. De Gaulle meanwhile had 70.000 Free French at his disposal although it must be said that only half of them were ready for battle.

North-Africa would witness the first military triumph of the Free French. The 1ième Brigade of the Free French, in co-operation with a battalion of Jewish volunteers (some 4.000 men all told) and commanded by the French general Marie-Pierre Koenig, managed to hold out against Rommel’s army near Bir Hakeim in Lybia for ten days. During the battle, heavy losses were inflicted on the German and Italian troops. On 10 June, the French were forced to abandon their positions however but two thirds of them managed to reach British lines. Moreover, French military honour was saved. When De Gaulle heard about the fights at Bir Hakeim, he was overjoyed. He wrote in his memoirs: "Oh, the heart thumping with emotion, cries of pride, tears of joy." Rommel’s delay also enabled the Allies to assemble a large concentration of troops at El Alamein where the Afrika Korps would suffer a major defeat in November 1942.

Conflict between De Gaulle and Giraud

On 8 November 1942, the Allies launched an amphibious operation in North-Africa. During this Operation Torch, more than 100.000 Allied troops came ashore on the coasts of Morocco and Algeria. De Gaulle was kept away from the invasion plans, probably on initiative of the Americans and only heard of them after the landings were completed. He allegedly was furious: "I hope the Vichy people throw them back into the sea," he ranted. "You cannot get France by theft." The Vichy were not thrown back into the sea however and Churchill managed to calm De Gaulle down during a personal conversation.

For a few days, battles were raging between the Allies and the Vichy-French. On November 11, 1942, after negotiations with the Allies, Amiral (Admiral) François Darlan, Supreme Commander of the Vichy troops, ordered the Vichy followers in North-Africa to lay down their arms. This order was obeyed by most of the troops, although they failed to take over the French fleet, as Churchill had hoped. As Germans troops threatened to capture the fleet, it was scuttled in the port of Toulon by order of Contre-amiral (Rear admiral) Jean de Laborde. The Allies lost 2.225 men, about half of them killed. The Vichy-French had some 3.000 victims to mourn. On November 14, the American general Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in North-Africa, appointed Darlan French High Commissioner for North and Northwest-Africa. This was done mainly to prevent a revolt by the Vichy French and because of the speedy manner in which Darlan had achieved the armistice in Africa.

De Gaulle was furious about this decision however; he wanted to have the territories in North-Africa ruled by the Free French and not by a collaborator. In December 1942, Darlan was shot in Algiers, probably because of his former collaboration with the Vichy regime, by Ferdinand Bonnier de la Chapelle, a 20 year old resistance fighter and monarchist. Darlan was succeeded by Henri Giraud, who had served under the Vichy regime as well but who had also contacted the Allies in connection with Operation Torch and who was in command of more troops than De Gaulle. The Americans in particular had more confidence in Giraud than in De Gaulle. De Gaulle temporarily accepted Giraud as the leader in North-Africa although there was much tension between the two.

At the Casablanca conference from 14 to 24 January 1943, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt forced De Gaulle and Giraud to negotiate in order to solve their differences. Definite agreements were not reached however. De Gaulle refused to serve under Giraud. He blamed Giraud for his initial support of Pétain, as he said himself: "There are no good French who have not followed me." The famous picture that was made of the two, shaking hands was taken under pressure from Churchill and Roosevelt.

During this conference, De Gaulle also had a conversation with the president of the United States. De Gaulle hoped to persuade the President to acknowledge the C.N.F. as the provisional government of France. Roosevelt had always mistrusted De Gaulle for his egoistic behaviour and he also assumed he was not fully backed by public opinion in France. Roosevelt argued he could not acknowledge De Gaulle’s committee because it had not been formed in a democratic way. To this De Gaulle answered that Jeanne d’Arc had not been elected in a democratic manner either. When Roosevelt complained later that de Gaulle did identify himself very strongly with this medieval heroine who had supported the French armies during the Hundred Year War (1337-1453) with divine intervention, Churchill is said to have remarked: "Yes but unfortunately my Church does not permit me to have the virgin burned.."

On 30 May 1943, De Gaulle arrived in Algiers. He moved the seat of the C.N.F. from London to this North-African town. He also changed the name, henceforth it was called Comité Français de la Libération Nationale (French National Liberation Committee or C.F.L.N.). It was intended that De Gaulle and Giraud would lead this committee jointly but in practice, this proved not to work. De Gaulle was far more popular than Giraud; he was supported by a large section of the resistance in France. A week after the establishment of the C.F.L.N., De Gaulle resigned, arguing he could not co-operate with the Vichy followers on the committee. Under pressure from public opinion, Giraud reluctantly agreed to a sharp increase of followers of the Gaulle on the committee in order to persuade him to return. By this and other political moves, the general managed to gradually sidetrack Giraud, aided by the fact that Giraud was highly incompetent politically and that he had made a few blunders. For instance he did not consult with the C.F.L.N. prior to launching an invasion of Corse on September 11, 1943 (although this operation had been approved beforehand by the United States). On October 2, 1943, Giraud officially resigned as vice-President. When the Allies found out Giraud still possessed his own spy network, De Gaulle forced him to resign as Commander-in-Chief of the French armed forces as well.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Casablanca conference

- Conference between the leaders of Great Britain and the USA (Churchill and Roosevelt). The conference took place from 14 to 24 January 1943.

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Vichy government

- Government in the unoccupied part of France, seated in Vichy. This government collaborated with the Germans. In 1943 France was completely occupied by Germany.

Images

Charles de Gaulle with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The two had a difficult relationship. This picture was taken on 13 January 1944 in Marrakesh, Morocco. Source: The National Archives UK.

Charles de Gaulle with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The two had a difficult relationship. This picture was taken on 13 January 1944 in Marrakesh, Morocco. Source: The National Archives UK. Général Marie-Pierre Kœnig, his brigade of the Free French managed to hold out against Rommel’s Afrika Korps near Bir Hakeim, Lybia for ten days.

Général Marie-Pierre Kœnig, his brigade of the Free French managed to hold out against Rommel’s Afrika Korps near Bir Hakeim, Lybia for ten days.  The Allied Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower (left), next to him François Darlan, the Commander-in-Chief of the Vichy-French armed forces. Source: U.S. National Archives.

The Allied Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower (left), next to him François Darlan, the Commander-in-Chief of the Vichy-French armed forces. Source: U.S. National Archives.The liberation of Western Europe

The Italian campaign

The Allied campaign in Italy was launched with the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943. On July 14, the first units of the French armed forces were deployed. These mainly consisted of Goums, Moroccan auxiliary troops who came from the Chaouia region in Central-Morocco. Before the war they had been deployed as police forces in the Atlas mountains. These soldiers could therefore operate well in mountaineous areas and they were also known for their resilience and marksmanship. In the Sicilian campaign, the Goums would distinguish themselves in a positive sense by their fighting spirit and because they could cope well with the difficult terrain.

The attack on the Italian mainland began with the Allied landings at Salerno. Initially the invasion progressed sluggishly and the Allies even risked being pushed back by the Germans. The Allies stood fast however and managed to make some progress later. Naples was captured on October 1, 1943 but subsequently, the Allied advance was stopped in its tracks on the Gustav line. This line (83.89 miles south of Rome) ran through mountaineous terrain, was heavily fortified and partly because of the beginning of winter, it formed an insurmountable barrier for the time being.

De Gaulle argued that French troops be deployed in the Italian campaign and this was granted by Great-Britain and the United States. On November 25, a French expeditionary force commanded by Général de Brigade Alphonse Juin came ashore. The Corps Expeditionaire Français, which was to form part of the American 5th Army commanded by Lieutenant-general Mark Clark, would ultimately have a complement of 65.000 men. Clark had asked for deployment of the French troops and in particular the North-African units. These operated well in this area where mechanised warfare was all but impossible and they proved themselves as good soldiers in Sicily. The C.E.F. was deployed on the right flank of 5th Army.

On 24 January 1944, the Allies launched a massive attack on the Gustav line. The French managed to cross the river Rapido and won some miles of ground at the cost of thousands of dead and wounded. The Americans could not force a breakthrough however. Mid February, the attack had to be aborted due to the heavy losses and the fact that the troops were near exhaustion. The armies were being reorganised and reinforcements brought in. The C.E.F. was granted a temporary respite but it did not last long though. The French expeditionary corps was transferred to another sector of the front, south of the Liri valley. On May 11 they took up the offensve again. This attack was part of a massive operation involving American, British and Polish (the Polish 2nd Corps) forces besides the French. The operation was successful and the German defensive line was finally breached. The Allied offensive progressed rather well from then on and Rome was liberated on 4 July 1944.

Preparations for D-Day

Roosevelt had given orders that De Gaulle was not to be involved in the preparations for D-Day. One reason was that the Free French were using an obsolete coding system that had been broken by the German intelligence service. Churchill did argue that De Gaulle should be informed just before the invasion of Normandy. This was done but it was also made clear to De Gaulle that the captured French territory would not come under his rule for the time being. Until elections could be held, all occupied areas would be ruled by a temporary military adminstration. De Gaulle was very upset about this: "Imagine me having to submit my candidacy for authority in France to Roosevelt or to you (Churchill). The French government exists all right. Politics and administration are our business."

A few week after the invasion, De Gaulle was permitted nevertheless to visit Bayeux, one of the first French cities that had been liberated. Notwithstanding the Americans, he established a provisional government, answerable to him and headed by a local resistance fighter. The British and Americans now became fully aware of De Gaulle’s popularity among the French population. The entire French resistance supported the general and the Americans could do little else but permit the provisional French government, headed by De Gaulle, to seize power in the liberated French regions. On 15 August, a second Allied landing (Operation Anvil) took place in southern France between Toulon and Cannes. Soldiers of the Free French also took part in this operation, namely the 1ième Armée commanded by Général Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. The operation was a success and Toulon and Marseille were liberated.

After the Allied breakout from Normandy at the end of July 1944, the advance progressed very rapidly. Meanwhile, the Free French could call on a force of 500.000 men in total. It must be said however that these troops were equipped by the Americans only. De Gaulle acknowledged that the French troops were totally dependent on the benevolence of the United States. Unfortunately, in his opinion the Americans were not always so generous, causing the French troops to revert to all kinds of tricks such as fraude and theft in order to receive the supplies needed.

De Gaulle had demanded that Paris be liberated by French troops and as the city was of little military importance, Eisenhower agreed. After the Paris resistance had unleashed a revolt at the end of August 1944, the 2ième Division Blindée commanded by Jacques-Philippe Leclerc de Hautecloque was ordered to liberate the city. Heavy fighting ensued but the German troops surrendered on August 25.

On August 26, 1944 De Gaulle made his triumphant entry into the city although German snipers were still active. A victory mass was celebrated in the Notre Dame and De Gaulle delivered a speech which would become famous: "Paris outragé, Paris brisé, Paris martyrisé, mais Paris libéré" (Paris has been dishonoured, Paris has been broken, Paris has been tortured but Paris has been liberated). The provisional government was moved from Algiers to Paris. On 9 September 1944, De Gaulle presented his new government including many resistance fighters but also a number of Vichy officials who had defected to the Free French at the last moment. On October 21, 1944, this new government was officially acknowledged by the United States. De Gaulle’s reaction was rather sober: "The French government is pleased to note that she will now be called by her own name."

Further progress of the battle

After Paris had been captured, the problems for France were far from over. The country’s infrastructure had been severely damaged, supply of foodstuffs was a problem, there was an enormous shortage of raw materials and the high inflation caused serious problems. By increasing the wages with no less than 40% and limiting the circulation of banknotes, the government headed by De Gaulle attempted to stabilise the economy and to put a halt to inflation. The government also issued a large state loan to which French citizens could subscribe. This was done in masses. In his memoirs, De Gaulle mentions a yield of 165 billion francs. In this way, the government received the necessary financial means.

Meanwhile, fighting continued on French soil like in the Vosges and in the Alsace. The war seemed to be already won but the Germans still put up a fierce resistance. De Gaulle himself did not mind though. He wrote in his memoirs: "The time that would pass until the end of hostilities would enable us to attain in time what is rightfully ours." On November 23, 1944 Leclerc and his 2ième Division Blindée captured Strassburg, the capital of the Alsace.

Following the Ardennes offensive and a German counterattack in the Alsace (Operation Nordwind), Eisenhower wanted to regroup his forces however and he orderted 6th Armygroup commanded by Lieutenant general Jacob Devers to retreat to the Vosges. This would mean though that Strassburg would have to be evacuated again. De Gaulle refused to accept this and ordered the French troops to ignore Eisenhower’s order. This resulted in a fierce argument between De Gaulle and Eisenhower. Eisenhower threatened he would no longer supply the French army if his orders were not obeyed. De Gaulle reacted by indicating that the British and the Americans would no longer have access to the French railways and the communication network. Churchill had to be flown in from England to mediate between the two adversaries. The British Prime Minister realised the symbolic value the city had for the French and he sided with De Gaulle. Moreover, the front had been stabilised early January 1945 and therefore evacuation of Strassburg was no longer necessary.

Colmar fell on February 9, 1945, heralding the last phase of the battle on French soil. At the end of March 1645, French army units crossed the river Rhine and set foot on German soil for the first time. The German cities of Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, Freudenstadt and Ulm were still occupied before Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945.

Definitielijst

- Ardennes offensive

- Battle of the Bulge, “Von Rundstedt offensive“ or “die Wacht am Rhein“. Final large German offensive in the west from December 1944 through January 1945.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- Gustav line

- German defensive line in the south of Italy to prevent the advance of the Allies.

- inflation

- An economic process of sustained increase in general price levels and devaluation of money.(loss of purchasing power)

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Mid

- Military intelligence service.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Alphonse Juin, commander of an expeditionary force of Free French which landed in Italy on 25 November 1943.

Alphonse Juin, commander of an expeditionary force of Free French which landed in Italy on 25 November 1943.  Charles de Gaulle addressing the population from the balcony of the cityhall in Cherbourg in Normandy on 20 augustus 1944. Source: U.S. National Archives.

Charles de Gaulle addressing the population from the balcony of the cityhall in Cherbourg in Normandy on 20 augustus 1944. Source: U.S. National Archives.Political career in post-war France

Position of France after the war

De Gaulle dreamt of restoring France’s position as a major power. During the war, this was not possible though. France could only provide ten divisions to the Allied armed forces and that was no more than a trickle. Yet, De Gaulle hoped for France to be designated one of the great Allied powers. During a meeting on September 12, 1944, he declared: "We believe it would be a great mistake to decide anything concerning Europe without us. Each human plan would be arbitrary and transient when La France would not have attached her seal to it."

This hope proved to be vain. Franklin Roosevelt had already dismissed France as a major power in 1940 after the country had capitulated so quickly to the Germans. Joseph V. Stalin declared he did not take a country seriously that had contributed less than 5 million soldiers. Only Winston Churchill felt something for France. Churchill believed it was imperative that a stable balance of power should prevail on the European continent. In his opinion, France played a major role in this. He also saw a guarantee in the strong leadership of De Gaulle that the country would not fall in Commmunist hands. This was a real possibility since the Communists were strongly represented in post war France.

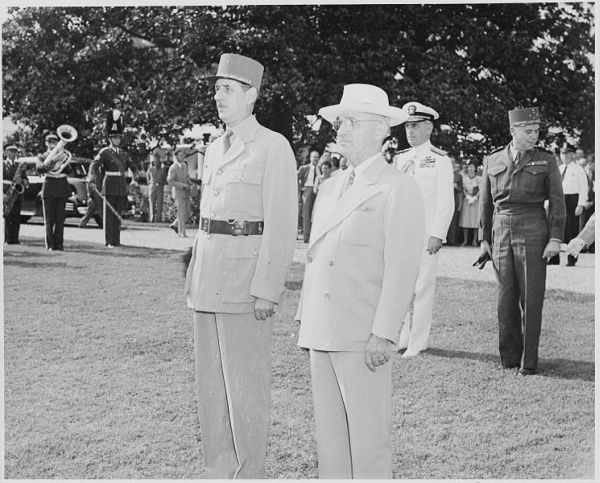

De Gaulle was not invited to the conferences of Yalta (February 1945) and Potsdam (July-August 1945) however. In these conferences, the post war dividing of Europe was discussed. De Gaulle later spoke scornfully about meetings between a cripple (Roosevelt), an alcoholic (Churchill) and a paranoid (Stalin). De Gaulle was obviously hurt he had not been invited to Yalta. When Roosevelt asked De Gaulle to meet him in Algiers after the conference, De Gaulle refused flat out. "If Roosevelt had invited me with good intentions, why then did he not invite me to come to the Crimea," De Gaulle wondered in his memoirs. Another reason he gave for his refusal was that the French President could not be invited by the American President to meet him in France since Algeria was still French territory at that time.

Yet, De Gaulle could not feel dissatisfied with the results of this conference. It was agreed that France would be involved in the peace negotiations with Nazi Germany and France was also allocated an occupation zone in Germany and Austria. Moreover, the country became one of the five permanent members of the Security Council of the United Nations, founded in 1945. France (along with Great-Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States) could count herself among the victors of the Second World War and was really designated as one of the greater Allied powers. These merits were mainly attributable to the work of Charles de Gaulle.

De Gaulle as Prime Minsister of France (1944-1946)

After the war, De Gaulle was the all but indisputable leader of the French. November 13, 1945 he became the Premier of the first post war government which also counted Communists among its members. In the elections of October 21, 1945, this party had won most of the seats. De Gaulle wanted to replace the Third French Republic and its continuing political differences that he hated so much, by a form of state in which executive power would be strengthened and the president would have a more important position. When it transpired that the parliament would not include such changes in the new constitution, which had to be drafted yet, De Gaulle resigned from politics in January 1946. He said about this "The absolute power of the parties has been revived. I reject this but apart from the violent establishment of a dictatorship, which I do not wish and which will undoubtedly lead to disaster, I do not possess the means to prevent this experiment. So I have to go. Later today I will address a letter to the chairman of the national assembly in which I will inform him of the resignation of the government."

1946-1958

In his own words, De Gaulle stayed away from politics during the following 12 years (1946-1958). This is not entirely true however. In 1947, he founded the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (Reunited French Population or R.P.F.) This political party represented the Gaullist ideology and resisted the constitution of the Fourth French Republic. Despite the fact that the party won more than 20% of the votes in the parliamentary elections in 1951, the movement never achieved a real position of power. Therefore, De Gaulle left the party in 1956. In the next four years, (1954-1958) De Gaulle retired, in his own words, in bitter resignation, to his villa in Colombey-les-deux-Églises in the Champaign region where he started writing his memoirs.

Definitielijst

- dictatorship

- A form of government where the power in a country is in the hands of one person, the dictator. Originally a Roman regime in case of an emergency where total power would rest with one person during six months in order to face a crisis.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

The return of De Gaulle

1954 was also the year in which a revolt against French colonial rule erupted in Algeria. Earlier that year, French troops had had to pull out of French Indo-China after they had lost the battle of Dien Bien Phu. They did not want to suffer another humiliating defeat like that again and certainly not in Algeria, for the country was not seen as a colony but as an integral part of France. It was therefore unthinkable it would be given up. The war soon escalated to a spiral of violence between the rebels and the French troops. Tens of thousands were killed and although the battle for Algiers was won in March 1957 by the French authorities, it did not manage to suppress the revolt.

In May 1958, French troops in Algeria rebelled against the government because in their opinion the government did not act forcefully enough. They called on De Gaulle and asked him whether he would take over power. At that moment, the outbreak of civil war in France was by no means imaginary. The rebellious French troops even had plans at the ready for an attack on Paris. On 29 May 1958, the French parliament also made an appeal to De Gaulle. He declared he wanted to take over power provided that he would receive special authorisations, rule six months without parliament and draft a new constitution. To the accusations that his proposals seemed semifacist, he countered:"In 1944 I have restored the Republic. Do you really think I will start a career as a dictator at the age of 67?"

On June 1, 1958, De Gaulle was elected President by the French population. Four months later, the French agreed to the amendment of the constitution which was the beginning of the Fifth French Republic which exists until today and which is characterised by a president with extensive executive powers and a modest role for parliament.

The end of the war in Algeria

The rebellious military and colonists in Algeria thought De Gaulle could solve the problems in the country once and for all. On June 4, 1958, De Gaulle visited Algiers and he spoke the famous words: "Je vous ai compris" (I have understood you). The colonists assumed that this meant Algeria would remain French. De Gaulle however gradually became aware that colonialism was a thing of the past and that the war in Algeria could not be won. De Gaulle called the rebellious military to order and transferred a few of them. A year later he announced that the population could decide on the future situation, independency or not, in a referendum. The Algerians voted for autonomy and on 3 July 1962, the country proclaimed its independency.

A large part of the French population agreed to the independency of Algeria. The military who had fought in Algeria did not though. Independency did mean they had fought and suffered in vain for years. As a result, a number of senior French officers founded the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète or O.A.S., the secret army. This terrorist organisation attempted to achieve the continuation of the battle in Algeria by means of bombing raids and assassination of prominent figures. The O.A.S. numbered more than 3.000 members and consisted mainly of (former) military personnel. Because of their experience, the organisations functioned very effectively. It is estimated that between 1961 and 1962 between 3.000 and 12.000 people lost their lives as a result of actions by the O.A.S.

De Gaulle, being the initiator of the Algerian independency , was of course one of the main targets of the O.A.S. He barely escaped two attempts. On September 8, 1961, a bomb exploded at the side of the road as De Gaulle’s car drove past but this bomb did not cause any harm. On August 22, 1962, De Gaulle’s car was fired at as he returned from a cabinet meeting. No less than 187 rounds were fired but the car was hit only 14 times and there were no victims. Hence, De Gaulle’s laconic reaction was: "They can shoot really bad." After a few top members of the O.A.S. had been arrested, including its leader, the former officer Raoul Salan, the organisation disintegrated rapidly.

De Gaulle as President

De Gaulle still fostered hopes he could revive the grandeur which France had enjoyed in previous centuries. He hoped to achieve this by measures such as a strong continental European co-operation (E.E.G.), headed by France and in which there would no place for Great-Britain. The E.E.G. (European Economic Community) was founded on March 25, 1957 and initially consisted of six countries: Belgium, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, France, Italy and West-Germany. The aim of the organisation was to increase prosperity by mutual economic co-operation and to minimize the possibility of conflicts. De Gaulle considered Great-Britain an extension of the United States and he wanted to push back the influence that country exerted on Europe. Therefore he did not permit Great-Britain to become a member of the E.E.G. De Gaulle also wanted France to have her own nuclear weapons at her disposal so she would no longer have to depend on the U.S. for protection in case of a possible war against the Soviet Union. He also tried to arrange that France and the U.S. had equal votes in N.A.T.O. When this proved to be impossible, De Gaulle reacted by leaving the military command of N.A.T.O. in March 1966 and expelling all American military personnel.

Definitielijst

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

A great statesman

Resignation and death of De Gaulle

De Gaulle remained in power for almost 10 years. In May 1968 however, massive demonstrations by students erupted in Paris. The students demanded a renewal of what they saw as a corroded system. The protests spread very quickly and resulted in massive strikes. De Gaulle was so shocked he paid a visit to the French troops stationed in West-Germany to convince himself of their loyalty. De Gaulle set up a referendum on a revision of the constitution, aimed at social and economic reforms. He offered the voters the following choice: they could either accept his proposal or he would resign. The voters rejected the revision and De Gaulle did as he had promised. On April 27, 1969 he stepped down as President.

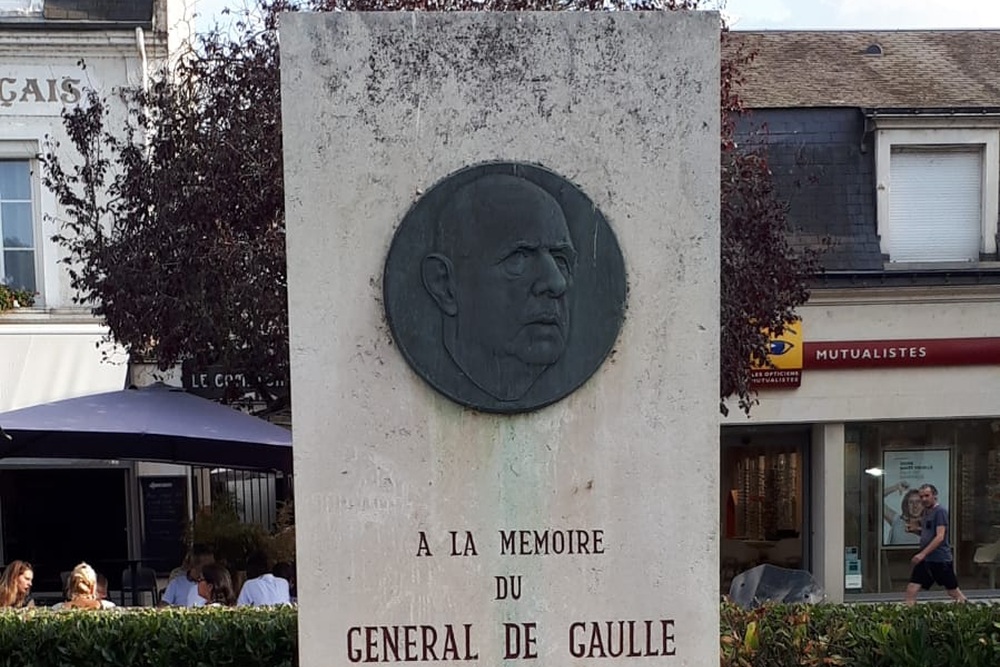

De Gaulle retired to his home in Colombey-les-deux-Églises. There, he passed away unexpectedly on November 9, 1970, due to a ruptured artery. At his own request, he was buried in the local cemetery, next to his daughter Anne who had passed away as early as 1948.

Epiloque

Charles de Gaulle is without doubt the person who has most personified France in the Twentyth century. By his unyielding attitude and his self centered behaviour, he rubbed many people the wrong way. As the story goes, Churchill would have remarked after the war: " I have had many crosses to bear during the war but the heaviest one was the Lorraine Cross." (The Lorraine Cross was the symbol of the Free French). Boris Jonson shows in his book "The Churchill factor" that this statement was not made by Churchill himself but by Major general Edward Spears, a special envoy of Churchil in France.

Charles de Gaulle did manage to save France from ruination twice though. In 1940 he prevented total surrender of the country by continuing the struggle from London and he managed to position France as one of the victors of the Second World War. In 1958 he saved the country from civil war and managed to solve the Algerian question.

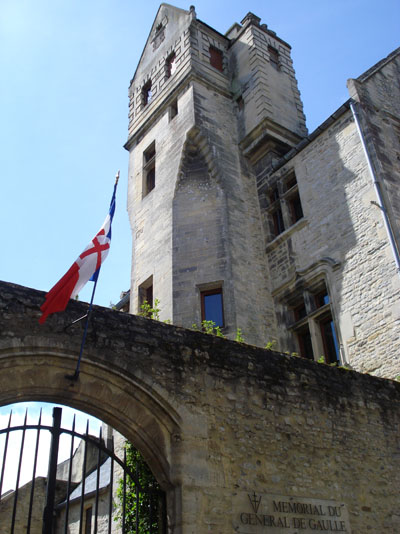

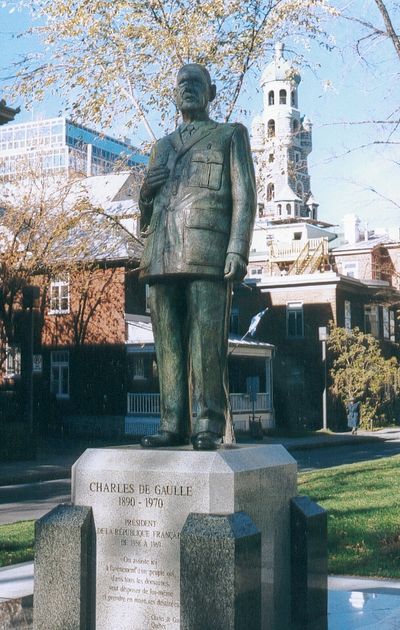

When the population made it clear that his regime was no longer desired, he resigned without protest. He has not been forgotten however. His name lives on in France’s largest airport, l’Aéroport de Roissy Charles de Gaulle and in one of the best known squares in Paris, Place Charles de Gaulle. Near Colombey-les-deux-Églises, a monument in the form of a Lorraine Cross, 144 feet high, has been erected. In France, more than 3.000 streets have been named after him and numerous museums are devoted to him. On 4 April 2005, Charles de Gaulle was chosen as the greatest Frenchman ever.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Wesley Dankers

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 20-03-2016

- Last edit on:

- 17-10-2022

- Feedback?

- Send it!

- 07-'40: How France's Warships Were Saved From Hitler

- 04-'41: Free French 'A.T.S.'

- 07-'44: The War at Sea

- 07-'44: Men of the Maquis are Striking for France!

- 09-'44: Armed Might that Gladdened the Heart of France

- 07-'45: Facts Behind the Syria-and-Lebanon Dispute

- 07-'45: Our Diary of the War

- 08-'45: Thoughts on the Peace of Potsdam

The War Illustrated

Related sights

Sources

- GORMAN, R.F. (Ed.), "Charles de Gaulle", Great Lives from History: The 20th Century, Salem Press, 2008, op: www.salempress.com.

- HAASNOOT, S., "De lotsbestemming van Charles de Gaulle", Historisch Nieuwsblad, nr. 2/2004, op: www.historischnieuwsblad.nl.

- KLINKERT, W., "De Marokkaanse militaire bijdrage aan de strijd tegen Nazi-Duitsland", Artikel 1, 9 mei 2005, op: www.art1.nl.

- SPRANGERS, R., "Aanslagen op Charles de Gaulle", Is Geschiedenis, 16 april 2012, op: www.isgeschiedenis.nl.

- en.wikipedia.org

- nl.wikipedia.org

- www.britannica.com