Introduction

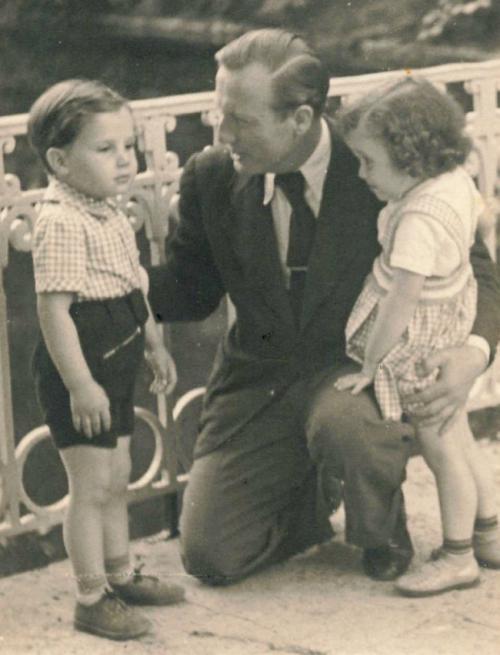

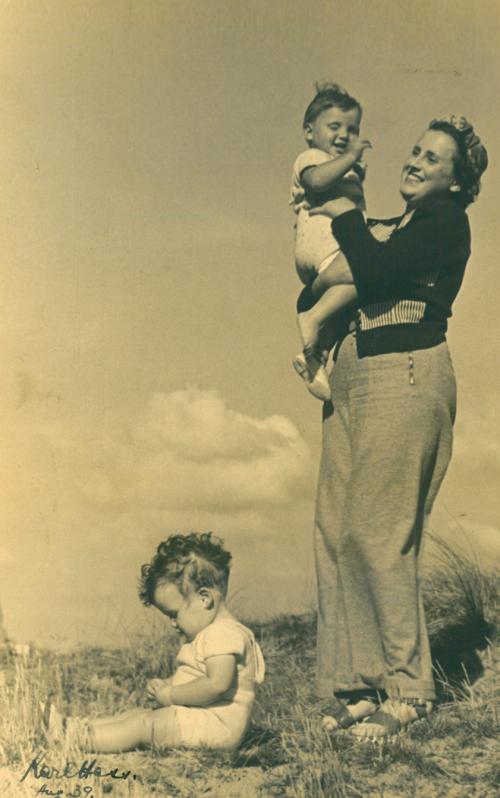

The following is the account Charles (Karl) Hess wrote in 1946 of how he and his wife Ilse Hess-Hirschberg and their twins Stefan and Marion survived the Holocaust. In 1935, the Jewish couple fled Nazi Germany to live in the Netherlands. Here the twins were born in Amsterdam on January 14, 1938. The family failed to flee the country when Hitler invaded the Netherlands in May 1940.

During the German occupation, Charles Hess went to work for the Jewish Council, which temporarily exempted him and his family from deportation to the death camps. In 1943, they were finally deported to transit camp Westerbork in the Dutch province of Drenthe. From there, they were deported to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany in February 1944. They survived the deprivations here and in the spring of 1945 were part of what came to be called the Lost Transport, a train of Jewish prisoners stranded in the German town of Tröbitz. On April 23, 1945, they were liberated here by the Red Army. Steven Hess explains:

In late 1944-early 1945, as the Soviets advanced from the east, the Germans started moving surviving prisoners from eastern concentration camps (Auschwitz, etc) to camps within Germany and western areas. This was most probably an attempt to hide the Nazi's murderous activities, impossible as that was. As a result, western camps, especially Bergen-Belsen became impossibly overcrowded from these "death marches" The camp became unsurvivable due to Typhus, starvation, exposure and mistreatment. The SS made a decision to move the so-called "exchange Jews" from the Sternlager. (Star Camp) to make room for those being driven west in death marches. The Nazis had planed in the early years of the war to keep, rather than murder, some Jews seen to have value for possible exchange for German POW’s , equipment, resources and, later, as pawns for possible better surrender terms.. Only a few hundred Jews were "traded" and thousands of others were murdered anyway.

In March 1945, with Bergen-Belsen one large graveyard, the Nazis planned to move about 7,500 half dead Jews west to Theresienstadt on three cattle car trains in the period April 6-9/10 (I write 9/10 because the last train left in the middle of the night and could have departed on the 9th or the 10th).

The first train was liberated by US troops in a few days. The second train arrived at its destination on April 23. The last train, "The Lost Transport" meandered through Nazi Germany back and forth trying to find useable tracks, while being strafed by allied fighter aircraft (it was still Nazi Germany and Allied pilots had no idea the cattle cars were filled with 2,500 dying Jews). We were on that train for 14 days and 13 nights. Several hundred died on the trains and many more later The train was finally stopped at the Black Elster River because the bridge was destroyed. The Soviets were already there and we were liberated.

After the war, in 1947, the family immigrated to the United States, where Charles passed away in 1981 and Ilse in 2003. Steven graduated from Columbia University and served in the United States Navy. He then worked in the photographic equipment industry until his retirement. His twin sister Marion worked in health care and public policy. We thank Steven Hess for giving us permission to publish the following account. We have left the text unchanged, but have added some endnotes.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

German occupation

Dear parents, dear sisters and brothers;

This is but a part of what we experienced while separated from you. It is meant for you, dear parents, and sisters and brother, and for a few good friends. It does not claim to be anything special; it deserves, however, to be remembered.

After we had spent a few happy years in Holland, the first days of may 1940 turned more and more grave and full of suspense.

On the night of May 10, 1940, Ilse, who had been aroused from sleep by the continuous drone of airplanes overhead, awakened me. It was about half past three in the morning. From our balcony we saw huge formations of German planes flying over Amsterdam.

War had broken out, and Holland was attacked.

We learned about military developments only from the radio. It was immediately announced that no Germans, which included us, were allowed to leave their houses. For three days we sat home in great suspense.

A Jewish neighbor who lived opposite us left with his family and with luggage in the direction of the coast. Other vehicles followed in the same direction. I had left my automobile standing in front of the door. After short deliberation, we put our twins, two years old at the time, in the car and tried like the others to reach IJmuiden in order to escape to England. We had to pass through repeated controls and barricades. There were eight air raids, so that all of us had to get out of the car and find shelter with the children. Either the children were lying in a ditch or we were standing with them, squeezed together in a huge crowd in some bakery or factory.

Only seven miles before our destination, we were stopped by Dutch guards. Since we were not Dutch, we were sent back to Amsterdam.

The following day the Germans marched into Amsterdam and that night we felt more miserable than ever before in our lives. We were trapped.

At first nothing unusual happened to give us cause for concern. The Germans were satisfied to pick up and lock up those Jews they had on their list.

Then came the Jewish laws. They were exactly the same as those that had been enacted in Germany itself. Everything was forbidden to Jews. Only a few stores were kept open for Jews from three to five in the afternoon. There one could buy what the others had left – which was nothing.

With more or less excitement, the years 1940 and 1941 passed. At the beginning of 1942, the Germans ordered a "Joodsche Raad" (Jewish Council) to be organized. This organization was supposed to act as the representative of the Jews for the Germans; the Germans did not want to have anything to do with the individual Jew but, according to the National-Socialist system, only with a few leading Jews.

This was the opening phase of the deportation. We had to be at home by eight o’clock in the evening; we had to wear Jewish stars on all our clothing, and we had to keep with us identification cards with a "J" (Jew) stamped on them.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Begin of the deportations

In July 1942, the Jews were informed that all men, eighteen to forty years of age, and their families had to go to Germany for the industrial effort. It is not clear who made the decision at the time that all German Jews were to be "called" first. It is my personal opinion that this was the way the Dutch Jews tried to throw a calf to the crocodile, in the hopeful attempt to be spared themselves. The calls to this unfortunate group came within one week, by mail. We received our call one Friday evening at half past five.

I want to point out here that it had been my opinion for many years previous that not even five percent of the European Jewry would be left alive. I knew at that moment that our own fight for life had started. The Dutch Jews – as well as, by the way, most the Dutch in general – were filled with a ridiculous optimism. They believed the war would be over in a few weeks.

Whoever had received such a call had to be at the end stop of the trolley which made this run only at one o’clock at night; that was, with his family and with his knapsack, the contents of which were written out. The nights before our call, we spent standing at the window. The city was veiled in darkness. Ghostlike figures walked out of their houses by the faint light of flashlights. One could hear the crying of little children and the tearful farewells of the old ones who had to stay back. By half past one, the trolley was crowded.

Living hardly thirty yards away from the end stop, we watched this whole drama, filled not only with the thoughts of those unfortunate ones, but also imagining ourselves being forced to walk this last road with our children. The trolley would start and the squeaking of the steel wheels taking the curves went right through our bones. Once again, good friends and acquaintances were on their way to the unknown.

According to our call, I had to report to the Germans at eight o’clock Saturday morning in order to pick up our "travel certificate". It was all done "legally", meaning that the Jew was deported even with official certificates. This evident ploy turned into a ridiculous farce. We had two hours left in which to arrange something because at eight o’clock there was curfew.

I went to the President of the Jewish Council, Mr. Asscher, the owner of the world-famous diamond house, Asscher & Co., whom we had known well for years.

At my suggestion, he made me his secretary, charged with the duties of an interpreter. This was, of course, a phony kind of position which had never existed before and would never exist in the future.

With a letter stating this, I went to the German authority called "Zentralstelle fűr Jűdische Auswanderung" (Central Administration for Jewish Emigration) and saw the head of the group, the Hauptsturm-fűhrer Aus Der Fuenten. He put a note on my call card – based on that letter – to the effect that the start of my work service had been postponed for six weeks. This way I had won the first round. Once more we could take a deep breath and consider what could be done next.

The following week it was the Dutch Jews’ turn. Now the stream of Jews broke forth in the direction of Germany.

After some time, however, those who had been called refused to gather at the trolley and, later on, at the train. The Germans saw themselves forced to get the Jews out of their houses. They were dragged from their beds at night and were hardly given time to take essentials.

In preparation for their final departure, the Jews were taken to a theater that had been turned into a detention facility by the Germans. It was the Hollandsche Schouwburg. The name was officially changed to "Joodsche Schouwburg" (Jewish theater).

One afternoon, our whole street was occupied and all the Jews were taken out of their houses. Among them, Ilse and me. When I asked a German solder – a huge fat hulk of a man – what was to happen to our children, he barked that the children had to stay in the house. "You and your wife, march-off-down the stairs!" You can imagine the horror we felt at the thought of having to leave our children alone in the apartment and being deported. In the street, all the Jews were standing in line, their backs to the row of houses. I asked a German guard if I could talk to the officer in command of this action ("Aktion"). The guard yelled at me and said that he would shoot anybody who dared move from his place. I said, "Go ahead, shoot." and calmly walked another fifty yards to where the officer stood. I asked him if it was his intention to have small children left alone in the apartment. He had watched the scene with the guard and said, "You have guts – send your wife back up to the children." So I was taken alone. I waited until the truck was filled and sat down next to the chauffer. The truck took us to an assembly point, from where the deportation was supposed to start. Getting off, I slipped to the side that was not watched by the Germans; they did not expect a Jew would dare to just run away. That night I spent in an office of the Jewish Council, and in the morning I was home again.

Often I sneaked out of the house at four in the morning and kept myself hidden in the bushes. Sometimes I hid in the beams of our house, or I slept away from our apartment, in hiding with Gentile friends.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Working in the Schouwburg

One day, the Jewish Administration picked a few men out of hundreds to work in the Jewish Schouwburg. As I mentioned, that was the building where the Jews were taken to wait a few days for another deportation transport.

The Hollandsche Schouwburg in Amsterdam, deportation center for Jews during the war. Source: Jan de Jager, TracesOfWar

I was picked for the work with a few others. It consisted of giving out food to the prisoners, to help them where possible and to alleviate the suffering during their stay in this building as best possible. We wore white armbands on our right arm, which had been inscribed with numbers by the Germans.

In the year I worked there, I witnessed the deportation of approximately 50,000 Jews.

As part of my routine, I left my house at six thirty in the evening and by seven o’clock, I was at my place of work. The shift was always twelve hours with no break. For weeks, night duty; rarely daytime work. The theater was guarded by the SS and the Dutch SD (Sicherheitsdients – security service). In general, the whole deportation was carried out by the Dutch SD – people who acted as helpers, spies and bloodhounds of the Germans.

At seven o’clock I took over from my predecessor. I was group leader of the night shift, consisting of approximately twelve to sixteen colleagues. At seven thirty, the food arrived, that was prepared by a Jewish restaurant in the city. We carried the huge buckets from the delivery van into the Schouwburg, passed out plates and fed the people.

Usually at nine thirty, the nightly round-up was started and at ten o’clock sharp the first truck would arrive with the arrested Jews. I had arranged the work in such a manner that the same three people would always go to the trucks. These men had the needed tact and calm when helping the unfortunate ones out of the truck. We helped carry the luggage of the people into the building and received the little children who, mostly crying, had been taken from their beds, not comprehending what was going on. For the next hours, one truck after another would come rolling in. This inhuman work would take until about half past tow in the morning. It is beyond description – how many tears of despair were shed there, what countless superhuman attempts were made to escape the claws of the persecutors at the very last moment.

At 2:30 a.m., we dragged about three hundred mattresses into the hall where the prisoners could get some rest. There they would be laying with their belongings, the women on the right, the men on the left. On the floors of the upper hallways would be lying the ones for whom we had no mattresses. Sometimes we had a thousand Jews a night in this prison.

I can well say that I, and the others, did our utmost to help each and every one, even if sometimes it was no more than with a comforting word.

The lights were put out. I made my rounds every hour in order to check if everything was all right, or if somebody needed a doctor. The most trouble I always had was with the ones who were unable to sleep, but would, with their babbling, disturb the sleep of those who, thank God, could forget their misery for a few hours.

In time we found out that it was possible to help some individuals to escape. The building was laid out in such a way that it was difficult for the Germans to watch it. At the head of our group was Walter Süsskind who had always lived in Germany, despite the fact that he was born Dutch. He was married to a woman from Giessen. He was quite a man, intelligent, courageous to the extreme, and ingenious in outwitting the Germans time and again. Of his case I have to make special mention because otherwise, in the following passages, it might appear that I was the hero, whereas in fact, (1) I did nothing but my duty and (2) in the beginning I acted on his initiative and, later on, at my own discretion.

It started with the fact that the small children, those who were still infants, were not kept in the building itself, but in a children’s home opposite the building. The women prisoners who were nursing mothers were allowed to leave the prison two or three times a day to nurse their children. On these occasions, I discovered that the Germans were casual in checking how many of the women returned. So, we started to let a few women disappear, and later on, we brought their children to where they were staying. At that time, we raised the age of "nursing mothers" as high as eighty years. Once in awhile, when the Germans found out, we just lied and said that this was the grandmother who had wanted to see her grandchild once more.

Later on, we turned this "helping to escape" into a whole illegal organization. No matter how exaggerated these figures may sound: in the course of a year, we secretly smuggled thousands out of the Schouwburg. Most of these people succeeded in hiding out with Gentile friends in the provinces. Others, unfortunately, were picked up again because they had been careless enough to return to their own homes.

With all due modesty, however, I can say that there is a rather large number of people who have survived deportation this way, and whose lives I have saved.

Whenever the Schouwburg was more or less filled, the prisoners were taken – on Friday afternoons, between two thirty and seven o’clock – to the Borneokade. This is a solitary railroad spur where truck after truck kept arriving, and where the train to Westerbork was waiting. At the Borneokade, I had a group of about eight people who gave food to the ones who were leaving on their journey.

Among our group were two women who walked through the train with a typewriter so they could take down messages for friends and relatives.

The train was barricaded by SD and Green police. Still, even there, we succeeded in letting people escape, partly through utter daring, partly under the protection of the winter darkness.

We ourselves always had one foot in a transport, but we kept at it. The fact that I had a wife and children at home, and that many of my colleagues had already been shipped off with these punitive transports, did not keep me from continuing my work for this great human cause.

How often have I, in the dark of night, led into freedom a person whom I had never seen before. I never had the idea that I was doing anything that would bring thanks. It was a tremendous satisfaction to have saved another fellow Jew from the hands of the tyrants. On the contrary, whenever somebody, almost delirious with happiness, would ask my name, I never told him – but implored him never to discuss his escape. Regrettably, the people who were saved this way only too often told of their liberation, and the Germans learned of it in round-about ways. That is why we were often put in situations I can recall only with a beating heart. As if by a miracle, we were always spared. That things like this happened may have been sheer luck, or the fact that the Germans themselves did not think it possible.

That year Ilse was sitting home with the children. She was a tremendous support for me during this difficult time. Sometimes at night, I sent a colleague to her to get me some food. Everyone of these colleagues returned, telling me that I had a very brave wife who not only did not get a shock if the bell rang at three o’clock in the morning, but who even offered him a cup of coffee.

In between, there were terrible raids, and the city would be blocked off in the mornings. On such an occasion, I worked right through for two days and two nights. Unfortunately, this experience left me with severe insomnia. That year I had to make do with four hours sleep in twenty-four hours, at best.

During the biggest raid that occurred, I realized the danger that Ilse and the children might be taking while I was working. I took our crew van to our apartment, quickly loaded Ilse and the children and tried to get them past the blockage. On the way we were stopped. The van was confiscated, the driver was arrested. On a brutally hot day in July 1943, Ilse, the children and I were standing at a street corner and seized by the Germans. No luggage, no food. Thus we stood for two hours. Again and again, I tried to influence the guard with the most fantastic lies that he should let us go, but to no avail. On the contrary, he wanted to put the whole family and me in jail because I had attempted to smuggle us through the blockade. For us, that would have meant direct transportation to Poland as punishment. We were loaded into a truck and my identification papers were handed to the driver. After the truck had started, I happened to recognize him. He was an executive sergeant of the "Green police". I told him a story that, against orders, my family had gone into the street, and I had happened to meet them. I, myself, had a pass for that day and was working. The trick worked. He stopped the truck, returned my papers to me and let us get off. On the way home, Stefan could not walk any more and, on top of it all, we were stopped about eight more times by police patrols. They did not arrest us, though, since we were within the blockade. Only one Dutch SD man wanted to seize us anyway, despite the fact that he knew me and was aware that I worked in the Schouwburg. Just as we were approaching our house, out came the SS who had gone there to pick us up. They had found the apartment empty, thanks to our escape attempt, and thought we had already been picked up. This way, we once more escaped immediate deportation.

Due to my work in the Schouwburg, I am one of the few surviving witnesses of those horrible deportations and mass expulsions of old people who were dragged out of the Amsterdam old age home. I was at the train when four hundred and fifty orphans arrived, who had been pulled from their beds in an orphanage. Those poor little children were all excited because they thought they were going on an outing. Only a few realized that they were being deported.

The old and weak were hauled into the train on stretches. How often we had to intone the "Sch’ma"[1] when one of these people, advanced in years or sick, died in our arms.

On Tuesday nights, the transports went to Vught, another Dutch concentration camp. The train left at two thirty a.m. We went with the people to the station. Pitch-dark, often raining, and above us the humming of the English bombers. Little children crying. The banging of the drinking cups which the people had tied to their knapsacks sounded like a continuous mournful accompaniment for this march.

In the meantime, Ilse and I made whatever preparations we could for our own escape. We got false identity cards, and we had found a hiding place for the children in the country. For ourselves, we had considered living in a small town as non-Jews. The dresses and clothes were out of the house, in hiding places, and everything was ready for the flight.

On the night of July 23, 1943, our bell rang at two o’clock. The "Green ones" came to pick us up. I showed them my pass, but, as we found out later, during this night all those who had a pass were being picked up. Under the pretext that our passes were supposed to be checked at the Schouwburg, we were taken along. We had to get our poor little ones out of bed and had hardly ten minutes to get ready. I, myself, was completely calm, because I was absolutely sure that we would either be released or that I would smuggle my family and myself out of the Schouwburg. My dear wife was less confident. Despite the fact that I did not think it necessary, she took at least some luggage along and that proved to be our luck.

We were transported in a truck to a large square which usually served as a stockyard. With another four hundred and fifty Jews, we stood there all night, until eleven o’clock the next day, in the open air, without food. The children were lying on the ground or running around between the pieces of luggage in the dark.

Our experience was this: If a family was transported to Westerbork with the one who worked in the Schouwburg staying behind, there was a small chance that the family could return or, for the time being, be released from the transports to Poland. For hours, Ilse and I deliberated if I should stay back so as not to miss this chance. My colleagues advised me to stay in Amsterdam, and I was uncertain until the last moment what I was to do. You see, in this place there was another group from the Schouwburg working. The moment I put on my white armband, which I always carried with me, nobody could tell if I was a prisoner or one of the Jews on duty.

However, I found it impossible to let my wife and children go by themselves. Ilse herself – who, to be sure, wanted nothing but the best for me – advised me to stay back. But I did not do that. I did give Ilse one last suggestion: to "faint" in the hall of the station and to simulate a seizure. She fell to the ground, screaming. The children cried with excitement and sat down next to their Mammi. Nothing worked. I asked the company commander to give me at least two days’ time to get my luggage in order. I pointed to my wife who was lying on the ground, supposedly unconscious. Nothing worked. We were put on the train. There we sat. The only treasure we had with us was a bottle of milk which somebody had given to us.

During the trip, we were outwardly calm, but desperate on the inside. Now we were really caught. The train rolled along, and in the evening we arrived at the camp Westerbork, from where the final deportation to the east took place.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Westerbork

On the evening of July 25, 1943, we arrived at Westerbork.

By name, we had known of the Westerbork camp for a long time because, before the war, it had been a Dutch detention camp. Approximately two thousand German Jews had been confined there. They had come to Holland, partly illegally, to escape from Germany.

The camp consisted of approximately twenty to twenty-five barracks located to the right and to the left of the camp street. The original camp inmates mostly lived in different barracks which were subdivided into small two-room apartments. Each room was occupied by one family or by several individuals. A railroad track ran through the camp street.

On arrival, we had to wait for hours, with our children, in the dense crowd, until it was our turn to be registered. After registration, we passed through one room where they took the rest of our money from us. I remember this situation very vividly. An SS man stood behind a desk where an SD official sat. This official called just one word to each new prisoner who filed past him – "Money!" There you got rid of your last penny, unless you wanted to take the risk of hiding it, which, on discovery, would have meant an immediate trip to the punishment barrack.

After having been subjected to quarantine, from where you emerged dirtier than you had entered, we stumbled, late at night, into the barrack assigned to us.

Such a barrack held sleeping places for about seven hundred people. The room for the men was separated from the women’s by a narrow entrance hall. The iron frames which served as beds were three high. All night long there was a continuous procession of those who suffered from diarrhea, which was a common camp illness. Most of the barrack-inmates wore wooden shoes – you can imagine the "nightly rest" where hundreds of people passed the long gangway past the beds. The gangway measured about thirty yards in length. In the washroom at the end of each dormitory, there was one toilet that could be used only at night. Besides that, in each washroom there was a long drain made of stone with about fifteen water faucets on each side. In this drain, you washed yourself, your clothes, eating utensils, etc. However, it was mostly used to dump the food leftovers and the contents of chamber pots, so that it was usually stopped up and unusable by the early morning hours.

Little red houses, the latrines, were our "quiet little places" for the day. They were located outside the barracks and consisted of approximately twenty-four holes, on which one sat, or rather stooped, one rear end next to another. In the seven months we spent in Westerbork, we did not once succeed in finding a "clean seat". The Westerbork latrines were the breeding place of sickness and disease.

The food was disgusting slop prepared in huge kettles and mostly arrived cold in the barracks. Personally, we did not mind this so much since we were permitted to receive packages. We did not starve in Westerbork. For this we had to thank, partly, Hermann Israel, Gottfried’s brother. Hermann was one of the old camp inmates who had been in the camp four years. He had a job in the potato kitchen and once in awhile he gave us potatoes, vegetables and milk for the children. In his unassuming way, he took care of us extremely well. With his old camp colleagues, he stayed in the so-called bachelor barrack, a barrack where only men were living. In this barrack, we could sometimes cook something for the children. Then, in the evening we would hurry into our own barrack, which was about a hundred and fifty yards away, with the huge cooking pot wrapped in old, filthy rags to keep the food warm. You are going to laugh about this: a few times we even prepared a gigantic potato schalet, and twice Hermann invited us for noodle schalet.

It was a burning hot summer. Countless flies were buzzing in the air. They would sit on every little piece of bread. These flies often made life unbearable. In addition, the sewerage was so poor that if the wind came from the south, the stench from the latrines filled the camp and turned your stomach.

Women and men had to work. Ilse worked as a children’s nurse. This way she could always be with Stefan and Marion. Through connections, I got myself a not too demanding job. Mornings and afternoons I had to sweep out a small barrack and twice a week I had to scrub it with water. I also had to clean latrines. The children played between the barracks in sand a foot high. This turned to thick mud with every rainfall. They looked it too, and Ilse had to fight the dirt continuously.

On Friday afternoons the mood in the camp would start sinking lower and lower. From that moment on, the weekly transports out of the camp were being readied. On the average, there were eight thousand to thirteen thousand Jews in the camp. The weekly number in the transports varied from one thousand to three thousand. From Friday to Monday there was this guessing game – who would be among those unfortunate ones? A desperate clandestine fight started, in which any and all connections were being sought so one would not be among them. Thus, Saturday, Sunday and Monday passed – under terrible strain and despair. Parents with small children were favorite "material for transport" because the children "filled" the lists. Monday, at ten a.m. like clockwork, the train would appear on the camp street tracks. It consisted of the oldest cattle cars a person could possible imagine, partly with hatches, partly all closed.

In the night from Monday to Tuesday, normally at two o’clock, the completed transport lists arrived at the barracks and were read aloud by the barrack leader. Per barrack, there were sometimes fifty names, sometimes one hundred, even two hundred names. It seemed to take an eternity for the last name to be read. Heart pounding and temples hammering, you would wait to see if your name was next. Then, those who were called jumped from their plank beds to pack their wretched belongings. We who remained helped those in complete despair to ready their luggage. We gave or collected foodstuff or other things for the selected ones. In the greatest rush, blankets were sewn together, all pieces of clothing were put on the children, one on top of the other – always hoping that this way, on the children, one on top of the other – always hoping that this way, one or the other thing might be salvaged. The atmosphere of these horrible nights of the transports can hardly be described. Even more miserable than the ones who were wailing and screaming seemed those who took their fate with total apathy. At seven o’clock in the morning, those who were to go had to step out in front of the barrack in order to be loaded into the cattle cars. Among them was always a large quota of very sick people who were included by the SS commander.

We witnessed fourteen such transports. In retrospect, I think that this was more gruesome even than Bergen-Belsen, since the emotional tortures were at the time much worse than the physical ones we had to endure later on.

In glaring contrast to all this suffering were the artistic events in the camp. The SS commander had a grandiose stage built where he allowed operettas, cabarets and musicals to be performed. The actors and musicians were Jewish camp inmates and, strange as it may sound, the orchestra of fifty men was absolutely first rate. Every night the theatre was filled to capacity. Unbelievable as it seems, on Tuesday evenings, after the transport had gone, there was not a seat to be had, despite the fact that most people in the audience had, only hours before, lost a loved one or a friend. For us, too, this contradiction of emotions was not to be explained. Perhaps one can possibly explain it by the fact that everybody was happy to have gained another week’s respite.

Meanwhile, we personally had added worries. Stefan, who had already undergone a mastoid operation in Amsterdam for a severe inflammation of the inner ear, had a recurrence and had to be taken to the Westerbork sickbay. The poor little fellow was lying there in a room with approximately twenty children. We were allowed to see him for only one hour a day. Medical care was so inadequate that Ilse once found out that the cotton wad was in the ear that was all right, instead of in the infected ear. Stefan hardly ate anything and got very weak.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Intermezzo in Amsterdam

For all these weeks, the Jewish Council in Amsterdam kept on trying to get the four of us out of the camp. Daily, hourly, we waited to be released. On September 18, 1943, we were overjoyed to learn that we were to be part of a small group of those who were permitted to return to Amsterdam.

At half past one at night, we lucky ones – few as they were – got together to start on their way back. Stefan was taken to the train from the hospital on a stretcher and was lying underneath all our blankets. In the morning, we were back in Amsterdam.

We had learned in Westerbork that a few days after our deportation, our apartment had been completely looted by the Germans and that other people were living there. Since we had no home on our return, Ilse went to the house of an acquaintance with the children. I stayed across the street with friends. On the following day, Ilse took our belongings to tailors, laundries and cleaners to try to restore our things that were utterly filthy and torn. We planned to wait for all these things to be fixed and for Stefan to recover completely and then go underground at the house of Gentile acquaintances.

A few days later, a good friend warned me of a massive raid that was to take place, so that the last remaining Jews would be deported from Amsterdam.

I immediately tried to get further information from Abraham Asscher and the other leaders of the Jewish community. They, however, knew nothing about it. We had our certificates of release from Westerbork and were relatively calm. In any case, I went to the center of the city to see what I could learn. That night, all the Jews were dragged from their houses. Three times I was in imminent danger of being taken and avoided arrest only by presence of mind. I tore my Jewish star off my coat and had myself thrown out of a building of the Jewish Council as an "Aryan", by a German trooper. He yelled at me and asked me what I, as an Aryan, had to do with the Jews.

When I came home in the morning looking for Ilse, the whole house was cleaned out and my dear wife and children were once more sitting in the train for Westerbork. Like a desperado, I rammed the locked door. Then I climbed, via a neighbor’s house, into the apartment which I found empty.

I stayed in Amsterdam for three more days. I forced my way into all the Jewish shops where our things were supposed to be cleaned or repaired. At night I roamed the streets like a criminal or looked for a hiding place. Our friends took care of me in a most devoted manner, trying every possible thing so I would not have to return to hell. However, after I had collected all our things on the third day – a job almost beyond human possibilities because the owners of those shops had been picked up as well – I could not stay in Amsterdam any longer. Hunted like a dog, I ran through the city, voluntarily surrendered to the Germans to be "permitted" to go to Westerbork. This was the smallest transport ever – one Jew wanted to join his wife and children, accompanied by two "volunteers", on a local train.

You can surely imagine the happiness of my loved ones on having their Pappi with them once more. As I found out, Ilse had stood her own deportation from Amsterdam most bravely. She had arrived at Westerbork on September 30, 1943.

The situation in the camp remained the same as we have described it to you.

Thus winter came, and in the camp there was an outbreak of infantile paralysis. It lasted six weeks. What we went through during that time cannot be told. Marion never did show the normal reflexes while being examined with the little hammer. We feared that she had contracted the crippling disease. Thank God, this was not the case. It started to get terribly cold and in the barrack there was a little stove that radiated warmth for barely three yards around.

Meanwhile, our friends in Amsterdam worked tirelessly to find a new way of helping us. For the equivalent of eighty thousand Gulden, we received a so-called "blue stamp". This stamp was given to a group of Jews who were slated for exchange.

In January 1944, the most gruesome transport ever left Westerbork, a transport of sick people. Almost the whole hospital was deported, along with all the families of the patients. It just so happened that all of us were healthy that week.

There was then only one way for us to get into a transport that was not going to the east, as fast as possible. We, ourselves, tried everything to get to Bergen-Belsen with the transport that was to leave on February 15, 1944. We had sensed the situation rapidly. To remain in Westerbork was impossible, since we had two small children. No matter how optimistic people were, in general, we were absolutely convinced that Theresienstadt meant Poland. Nobody knew anything about Bergen-Belsen because only one transport had gone there with Jews who had certificates for Palestine, dual nationalities, or, like ourselves, blue stamps.

On the night of February 14/15, our names were called. We were to go on the transport to Bergen-Belsen on February 15, 1944.

On February 16, 1934, the Justice of the Peace had married us. Ten years later, on the same day, we sat on the train to Bergen-Belsen. We will probably remember this miserable anniversary for the rest of our lives.

Definitielijst

- Jewish star

- Star of David on a yellow background which had to be worn by Jews in Nazi Germany and occupied territory during World War 2.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

- trooper

- Short for paratrooper.

Bergen-Belsen

In the afternoon of February 15, 1944, approximately eight hundred Jews left the Westerbork camp in the direction of Germany. The Jewish camp commander[2] made me the leader of the transport. All the doors were locked from the outside, except for the one to our compartment so that I could do my job. At half past two at night, everybody received a quarter of a loaf of bread as their supply for the trip.

We were in Germany. We saw Hannover. We stared at a ghostly city of ruins. In those fairly dark hours of the morning, it probably appeared even more ghostly than it really was. On secondary sidings, we rode towards Celle. At about eight o’clock, we stopped in the middle of a forest. This was the station of Bergen-Belsen. SS guards, rifles at the ready, encircled the train. We were yelled at and commanded to get out of the compartments. The camp itself was about three miles away from this station.

Everybody had to walk – mothers, children, the aged and sick. I stayed back with thirty volunteers to watch over the transport of the luggage. It was hours later when I arrived at the camp. All of our people, including Ilse and the children, were still standing outside in bitter cold, awaiting registration.

The whole camp was a maze of barbed wire. Each barrack, each unit, had its own barbed wire. The whole camp was encircled with high watch towers, approximately two hundred and fifty yards apart, and manned by SS with machine guns.

Since they had not expected our transport, we had to wait until late evening, at which time we were chased like a herd of cattle into empty unheated barracks. Imagine a horse stable (the barracks were, indeed, former stables) with wooden bed stands, always two, one on top of the other, a straw mattress with but little straw, no light. That was to be our "home".

The first four weeks we spent in quarantine, separated from the camp inmates who had been in Bergen-Belsen for some time. During that time, we did not have to work in squads. We had to get up at seven o’clock. Everybody had to get out of the barrack, which we alternated in cleaning with branches. Those who waited stood in the icy cold for hours until they were allowed to get back into the barrack. From ten thirty to eleven o’clock, there was roll call, where everybody, even the sick, had to appear. We did, however, have some physical reserves left, also some foodstuff, which, as by a miracle had not been taken from us. Thus, these four weeks were somehow bearable, despite the terrible cold. Ilse, the incomparable housewife, always managed to prepare this or that on a small stern-type pocket stove. In retrospect, I see her as the "mother" (from the book of Schalom Asch[3]) whose cooking-pot kept on delivering something even when I thought that everything had been eaten up for the longest time.

During the fifth week, we were brought to the camp itself and put to work. At a quarter to five, everybody had to get up, and at a quarter to six, all work units had to appear on the "parade ground". I, myself, worked with the "shoe commando". This unit of about five hundred and fifty men left the camp at six o’clock and marched to different work barracks located outside the camp. There was a circus tent filled with, believe it or not, eight hundred thousand old shoes which had been collected by the Hitler youth from all over Germany, and which we Jews now had to take apart so they could be used over for different purposes.

About one hundred of us sat in an ice-cold horse stable. Each received a shoe knife with which he had to rip apart the shoes just above the sole. It was disgusting work. Aside from the fact that the shoes were stinking and partly decomposed, the physical effort was great. The shoes were wet and the knives were dull. The dust settled in the lungs and our physical strength diminished visibly. The minimum output per day was one hundred pairs. If you did not achieve that, you were either beaten or you had to stand at the camp fence during noon recess instead of eating. For repeaters, there was the bunker as punishment, i.e. that you were locked up in a subterranean cellar for a few days and night without warm food.

Ten minutes before noon, the section leader’s whistle sounded outside. Five hundred and fifty men ran out of the barracks like a herd of wild animals to stand outside in rank and file. Then the call sounded, which we will never forget: "Vordermann und Seitenrichtung" (a German army command to fall into ranks and line up). The Dutch within our group imitated this call of the SS and yelled: "Voddeman en Zijkinrichting". The Germans considered this as a repeat of their command, but in translation, it means "ragpickers and pissoir". As you can see, even under these tragic circumstances, our sense of humor never left us.

At twelve o’clock, we were in the camp, as well as all the other work units, together with several thousand men and women. After the command "dismissed", we had exactly thirty- five minutes left before we had to reappear on the parade grounds. The ground shook from all these starving people running away and rushing into their barracks, each hoping to be the first to catch a pail of cabbage soup. The last one hardly had five minutes’ time to just lap down the food without a spoon and immediately to run back to the parade ground. Of course, we never had time to wash our hands before eating. They were pitch black and stinking, covered with welts.

At a quarter of one, we again left the camp and worked until seven o’clock. Many accidents happened when the shoe knives slipped. Once I cut my wrist and, by a miracle, things went all right that time.

Another unit had to saw tree trunks into pieces. The Germans, in their devilish irony, had formed this group from rabbis and wearers of eyeglasses. There were about fifteen different units for men and women. Almost all of them had to do hard labor, except the few lucky ones who had jobs in the kitchen or the storehouse for foodstuff. At the time I was desperate because I did not succeed in getting into that latter group because those who worked there never starved. Today I am happy about it. I had to thank my unusually bad reputation with the SS for this "failure". So, there was nothing else for me to do but to spend months with the shoe commando. In time, all of us looked the way the SS wanted to have us look – ashen, filthy, our clothes torn, our backs bent. We shuffled to our places of work, but in rank and file. Already we lacked the strength to walk like normal human beings. Our feet just did not carry us any more.

Meanwhile, Ilse carried on a superhuman struggle so as not to be placed in a unit that had to work outside the camp. In the beginning, she succeeded, through connections, in working inside the barracks, which was supposed to be reserved for women past fifty-five years or mothers with more than three children. Ilse had to scrub the barracks, scour the wooden stools outside, even in snow and ice, and take care, as best as possible, the children who were aimlessly running around in the barrack. Because she was strong, as well as one of the youngest of the women working in the camp, she had to fetch, together with a few men, the pails of food, carrying twenty-five and fifty liters, from the kitchen gate, about two hundred yards further than the barracks. We were, however, obsessed with the single idea that Ilse had to remain in camp at any price so she could look after the children now and then. They had nothing else to do but play in the dirt that lay several feet high.

All the women and men, the sick as well as little children who were kept inside the camp, had to appear at roll call at nine o’clock to be counted. This roll call cost the lives of thousands. It took from one to four hours. The worse the weather, the longer it took. At times, the SS took pleasure in holding it sometimes twice or three times a day, very often in the evenings, and as an additional treat on Sundays. The children would lie down in the mud because they simply could not stand up any longer. For Ilse, these roll calls for counting purposes meant hours of fear and terror. As a rule, the SS would ferret out young people to make them part of the work commandos, i.e. one had to appear at a quarter of six on the following morning for roll call for work. Ilse disguised herself as an old woman, tried to hide behind tall old women, or surrounded herself with Stefan and Marion so as not to leave any opportunity untried. For awhile this worked, until one day fate caught up with her and she was taken out of the roll call for counting and put into another shoe commando. This was a heavy blow to us.

While it was still dark, she left the children, returned home for half an hour from work, around noon, and used this time to force the disgusting food down the children’s throat. I don’t believe that she, herself, ate at all at that time, since she did not even have time for it. In the evening, she returned in the dark. It was always a guessing game if the children were washed or had something to eat. One day Ilse had to work in the clothing depot, a stockroom for uniforms of the Wehrmacht, shoes, underwear, etc. During an air battle in the afternoon, several barracks of this depot had been hit and caught fire. From an SS man, Ilse learned that several barracks inside the camp had also been hit. You can imagine her fear for the children. No amount of imploring worked, however, and she was not allowed to leave her work. When Ilse came back to the barrack in the evening, she found everything in chaos. A night nurse, who used to sleep three beds away from Ilse, had been killed. Above the beds of Ilse and the children, shell splinters had burst. Fortunately, nothing had happened to the children, but they were still shaking all over. That day Ilse swore to take any risk, as long as she would never again have to leave the camp. She carried on her private war against the SS, and she really succeeded in never leaving the camp again up to the last day in Bergen-Belsen. During roll calls for work, Ilse used to hide in the latrines. Whenever she was gotten out for count out, she simply did not go to work. We accepted the possibility of being punished with bunker arrest or deprived of bread. This would have been nothing as compared to leaving the children without supervision, even for one hour.

One day Stefan had a recurrence of his inflammation of the inner ear. A thick crust of pus had formed on the scar from the operation, and our poor little fellow had to be taken to the hospital barrack with a very high fever. The doctor said that an operation would have to be performed immediately, but the instruments had to be gotten first from outside the camp by the SS. This took several days, during which time nature took its healing course. Like a medical miracle, the infection opened up by itself, the fever dropped, and our little darling revived in spite of total weakness. Visitors were allowed in the sick bay only twice weekly. That is unbearable for a mother. Ilse moved heaven and earth to bring about a change. Finally, with the help of doctors, she managed to be employed as a cleaning woman in the sick bay. This way, she was always admitted to the hospital barrack. When the superior commander caught her in her new job, he fired her, scolded the doctors severely, and gave the order to employ old women exclusively. But one SS orderly, who was quite taken with Ilse’s "cleaning", put in a good word for her and she got a pass from the company commander, saying that she was officially appointed in the sick bay. We were much relieved because Ilse did not have to attend roll call any more, since the sick bay personnel were allowed to remain in the barrack. For Stefan, this meant a piece of well being because Ilse was now able to take care of him. Unfortunately, we had nothing we could have given him additionally, since the patients, too, got nothing but kohlrabi soup. We saved some of our bread rations, which we exchanged for a marmalade jar filled with sugar and a few spoonfuls of oatmeal. With this, we helped our patient get back on his feet.

Ilse’s work in the sick bay was probably the filthiest and most disgusting that anybody can imagine. She had to clean the toilets; I prefer not to describe what they looked like. The wards were in a sickening condition. In the so-called "laboratory", there were the uncovered corpses on the one bench and the bread for distribution on the other. But Ilse saw nothing but "sun", because finally she had a "secure position". Later on, the orderly "promoted" her, and she only had to clean the outpatients’ department and the physicians’ room. Besides that, Stefan and Marion could always reach their Mammi. Even they were shocked seeing Ilse in this unbelievable filth. Often the sick bay was without water and cleaning materials for days, but the mess had to be done away with.

The number of dead mounted daily. One Sunday morning, the orderly asked for the number. There were twenty-six. He said, "Because this is Sunday, I guess I will be satisfied, but tomorrow this will have to improve." This sentence clearly shows the tendency of Bergen- Belsen. They had figured with mathematical precision how long it would take for a human being to perish under the hardest labor and starvation.

Conditions in the camp also turned ever more gruesome. Only spring and summer and the general progress of the war – about which we occasionally learned from the commandos on the outside – gave us a bit of hope and kept us going. The food situation kept getting worse. The soup consisted of no more than water with a few little pieces of kohlrabi and a daily ration of three and a half centimeters of bread. This measurement originated from the fact that always six people together received one loaf about ten inches in length. Added to this was the satanic pleasure the SS took in having us move into different barracks every few weeks. In the beginning, we shared a barrack with approximately one hundred and sixty people, later on with approximately six hundred.

At capacity, the camp could hold approximately six thousand people. Huge transports kept arriving, prisoners from other camps, starved, half dead, mistreated. Finally the camp was crammed with fifty thousand human beings. One day, next to our camp, a group of emaciated, non-Jewish prisoners arrived who were supposed to "recover" in Bergen-Belsen. The first command for those poor people was that they were forbidden "to die in the barrack". If they felt their end, they had to die in the open. In front of this barrack, there were hundreds of corpses lying each morning. They had to be undressed by their fellow-sufferers who had possibly another few hours to live. Then they were dragged, thick ropes tied around their arms and legs, to a collection area and thrown with pitchforks onto a wagon. A sickening sweet stench from all the corpses filled the whole camp. For the children, the view of the corpses was as normal as it should have been of dolls and rocking horses. They were so starved that they were able to eat a little piece of bread that had been lying among the corpses, and eat it calmly.

I, myself, was in a terrible physical condition. Hunger dominated me completely. My face and my legs were twice their normal size from hunger edemas. Only my stomach never betrayed me, and I am convinced that it has saved my life. Ilse and the children together ate one single portion of soup; the very sight of the food pails was so disgusting to them that they preferred starving to eating this fodder. This way, I had, together with my own portion, three lunches all to myself. While my colleagues suffered from dysentery and their bodies were so weakened that they even refused food, I was obsessed with one single thought – how I could obtain another two or three portions. There were days when I was the lucky owner of seven to eight liters of kohlrabi that, unfortunately, did not mean much for me either, because after half an hour, I was just as hungry as before.

The three and a half centimeters of bread were no more for me than an appetizer. While everyone else considered himself rich with the slices he would manage to get from it (there have been records of up to twenty-two slices), I ate my bread all up the way I got it. Despite the fact that I really suffered terribly from hunger, I was completely unbroken mentally. For hours, I could dream of the beautiful things in life; I saw myself at the theater, listening to good concerts and taking fabulous journeys.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Typhus epidemic and mass starvation

The moral decline in the camp kept pace with the steady worsening conditions of existence. Human beings turned into animals. The lice came. Typhus and paratyphoid fever broke out. The camp was so overcrowded that we slept, two together, on one straw mattress. With any luck, the bedfellow was a close acquaintance. If you were unlucky, you slept next to a stranger. No matter if the other one had a high fever, if he evacuated in the bed, if he suffered from a severe and contagious disease – there was nothing to be done, one had to sleep next to him. At night, I had the worst fights with my bedfellow. In the dark, we fought like animals for every centimeter of mattress. Sometimes I had to leave my bed ten times, since the sphincter muscles did not work, neither the front nor the back ones. Dripping sweat from weakness, one left the mattress and through the darkness stumbled out into the icy winter’s night to go to a latrine that was two hundred yards away and could be found only by groping in the darkness. There, in the open, shivering with cold, one had only one thought – not to sit down, but to do what one had to do in a crouching position. Snow or rain whipped the debilitated body and, finally, in exhaustion, one did fall onto the seat and looked accordingly, since the latrines flowed over at any time. Men and women used the only latrine of the camp together. Paper was non-existent. There was no water. One almost suffocated in filth.

The lice came by the legions. They overran your face; they covered your body; they crawled in the beds, in the underwear and in the clothes.

Everybody fought for himself like a savage. Baseness, egotism, hypocrisy were triumphant. Mothers ate the last little piece of bread out of their children’s mouth. Rabbis stole the last bite from their neighbors. Dante’s Inferno had broken loose. Death was the king of the camp. Families died in terrible maxims; first father or mother, then usually one child after the other. Twenty year-olds looked like old men and small children like emaciated old dwarfs.

Corpses were lying for days, uncovered, on the parade ground, in the barracks, on the straw mattresses, next to their bedfellows who were still alive. Of our Dutch group, which originally had consisted of approximately two thousand people, only forty-two were able still to appear on the parade ground. The rest were lying helplessly on their beds.

Bergen-Belsen, April 1945. Women inmates gaze at the naked body of a child who has died of starvation. Source: Imperial War Museums

There was no more bread, only raw kohlrabi. Like starving little birds, our children sat on their three-tiered beds. No more did they speak, no more did they laugh. They did not complain, they did not cry, they were just apathetic.

More and more transports kept arriving. One day, two thousand prisoners came, arms linked, always five in a row. When this transport halted and the prisoners had to let go of each other, they dropped. Half of them were dead.

I was perfectly aware of the fact that we, too, would have to pay the final price. I had resigned myself to the fact that the four of us would never survive this hell. I prepared for my own death. On the outside, as well as within, I was completely calm. Towards Ilse, I always emphasized that we would have to start on our last road courageously. The fifth of February 1945 was the day of my death.

On orders of the superior section leader, Rau, I was taken out of my barrack and commanded to clean out a filter plant outside the camp all by myself. The filter plant was a basin measuring approximately three and a half by two meters and as deep as a manhole. The basin was filled with human excrement that flowed from a drainpipe out of the camp. Two superior section leaders awaited me and watched the work. First I tried to alleviate the stoppage with a pole. When this did not proceed fast enough for the SS, they ordered me to undress. Thus I stood on a bitter cold day, on the rim of the basin, clad in nothing but my pants. The SS threw me into the excrement and ordered me to dig up the filth with my hands. Since the waste pipe was at the bottom of the basin, I had to dive into the filth while they beat me with their rubber truncheons. Twice I tried to crawl out of the basin. Each time, they threw me back into the nauseating filth. I asked for a short reprieve in my work, which was granted. At that moment, while I was lying on the ground, I was beaten and kicked so badly by the two SS men that I knew my end had come. Calmly I asked section leader Hertzog to shoot me and end this satanic torture. High in the sky a flock of crows was screeching. Diagonally opposite, I saw, through the partly opened door of the crematorium, a heap of corpses. Those were my last impressions of this world. This mistreatment lasted four hours.

I used the coffee break of the one section leader for softening up the other one to give me a break in my work so I could put on dry clothes. How I got back into the camp I don’t know to this day. From the kicking, my head was swollen so badly that it looked like a clown’s head, the kind one puts over one’s face at a circus.. My battered ribs hurt. In the camp, my fellow- sufferers stared at me with shock and horror. Even those who had themselves shared in the most brutal mistreatments had never seen a man so badly beaten about, almost beyond recognition. My eyes were closed, my mouth hung somewhere in my face and not even Ilse recognized her own husband. Ilse decided that I was not going to return to work under any circumstances, come what may. She took care that I got a plank-bed in the hospital, which was a tremendous achievement because a mattress became vacant only after somebody died.

That same evening I had a high fever, pneumonia and pleurisy. As Ilse told me later, the doctors had given up on me. She also told me that I kept asking for a mirror and that she had forbidden everybody to let me have one.

For nine weeks, I was lying in the hospital barrack, never thinking that I would describe my own death. To my right and left, people died like flies. The whining and moaning of those fighting death was our unending night music.

Slowly the whole camp was in a condition of dissolution and decay. Typhus decided on life and death. One single infected louse was enough to transport you to the next world. And everyone had lice. The children played with lice.

For some time, the camp had been under the command of a political prisoner who had been nominated for that post by the SS. He was a professional criminal whose assignment it was to "liquidate" the camp, i.e. to liquidate the people. Fortunately, he picked some girl friends for himself from the female camp inmates, and this diversion slowed down his plans.

Definitielijst

- liquidate

- Annihilate, terminate, destroy.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

The Lost Transport

The allied troops kept coming closer – thirty miles, twenty-five, ten miles. The SS got nervous. The kitchens did not function any more. The corpses were not picked up any more and piled up like mountains, thousands per day. A sudden order: "The camp will be transported." Through secret connections, we learned that we were to take an extended trip, which was to last fourteen days, in cattle cars. I am not proud of the fact that my premonitions were always correct. But, as we later found out, my assumption was right. The trip was supposed to lead to the gas chambers.

The first part of the camp left. A few trucks were supposed to transport the severely sick. When they arrived, the healthy ones stormed them. Without any consideration, women and children were thrown to the ground. Those who found no space on the wagons had to walk the five kilometers. From previous reports, we knew that whoever could not keep up on the way was shot. We let the first transport leave in the vague hope that the English, by then only fourteen kilometers away from the camp, would be able to liberate us. But a bridge was blown up and that delayed their advance.

On April 10, 1945, our transport left. It was the first day that once more I was standing on my legs, i.e. that I practiced walking like a child. Ilse carefully selected a very small part of our luggage. I sold my last suit, practically new, to a prisoner for three quarters of a liter of kohlrabi. We stumbled out of the barracks into the throng of thousands of people who were lying, sitting or standing on the camp road, each ready to jump and grab a seat on the three trucks which were to take us to the railroad station. There ensued a wild melee. The section leader pulled his gun to keep us in check. We had to thank the lucky coincidence that this section leader knew me from a transport commando; this way the four of us were allowed onto a wagon.

When we arrived at the loading station, we noticed a tremendous train consisting of a few very miserable passenger coaches and, for the major part, old cattle cars. Provisions for the trip were put next to the train, i.e. a huge mountain of raw kohlrabi, of which everybody was allowed to take some. We walked along the train – every seat was taken. Finally we found a cattle car in which there were already forty-five Hungarian women. There we found room.

At the end, we were fifty-seven people in this car, i.e. fifty-four women and three men. The accompanying SS nominated a car leader for each car. As if this were an eternal chain in my life, this time, too, I was nominated "leader". There we were, lying and sitting, crowded into this tiny space, without water and without a toilet, with very little bread and raw kohlrabi, and ahead of us a trip of fourteen days.

The doors were closed and in the evening of April 10, 1945, a gigantic train started rolling. Twenty-five hundred Jews were its cargo, towards an unknown, new destiny.

None of us knew how to manage at all within these few square meters, since there were neither seats nor any other provision for human beings. We arranged ourselves along the walls so as to leave the middle free for the few pieces of luggage. Ilse, as "the wife of the car leader", enjoyed the small advantage of being able to sit right next to the door with the children, so they got a little fresh air. Despite the fact that we traveled towards an unknown fate, our inner excitement was mixed with a scant joy. For the first time in years, we were outside a barbed wire.

The train went in a northern direction. At first the SS did not permit anybody to leave the car during the short stop, but, in the long run, they could not keep up this restriction because, as I mentioned, there were no toilets in the cars. Inspired by some sadistic baseness, the Germans had loaded people suffering from typhoid fever along with the healthy ones. The train hardly stopped when one of the corpses would simply be thrown out of the car to find his last resting place, unburied, next to the tracks. We mourned one hundred and ninety-five dead on this trip of thirteen days.

The short supply of food was soon used up. Since the trip from Bergen-Belsen had not been prepared for in any way at all, there had been no arrangements made for feeding the prisoners. After a few days, hunger drove us out of the train. Even with the SS shooting off pistols as soon as somebody left the car, one took the risk to get out of the train. Sometimes the train stopped for one minute and sometimes it remained standing in some lonely place for a whole day. This, of course, we never knew in advance. On the fourth day, I left the car and went, as if guided by a divining rod, to a nearby forest, and there I found … a potato field, which I dug up with my bare hands. It was a gold mine. Sixty-four potatoes I stashed in my pockets. I returned to the train like a king. Ilse always had to pull me into the car, since I was too weak to get up there by myself. Under my breath, I told Ilse and the children about my loot, and we decided that each one would be allowed to eat six potatoes to celebrate our good fortune.

Because only a few of the twenty-five hundred people were in possession of matches, the fire had to be gotten by way of relay, with grass or dry leaves, from as far away as sixty meters. Then the cooking could start. We built our "oven" from small stones. We used leaves and small pieces of wood for fuel.

Our bowl from camp, which served for washing, cooking and eating, we filled with water that we sometimes caught from the locomotive, or skimmed up from some dirty puddle. Ilse would lie flat on the ground and fan the fire by puffing for hours, while I had to keep searching for more and more new pieces of wood, and breaking them. Later on, we were the fortunate owners of two bricks on which the bowl stood more firmly. How often, during cooking, a shrill whistle would sound – a sound that the train was going on! Then, we first threw the glowing hot, irreplaceable bricks into the car. Afterwards, we jumped, with the children and the boiling water, onto the train that, in most cases, was already moving.

The train had hardly stopped when we "installed" our ‘kitchen" in front of the car. This way our potato cooking sometimes took one hour, sometimes more than one or two days.

During the whole trip, Ilse had a very high fever. Most of the time she, herself, was not aware of it, but her eyes were so glazed that there was no need for a thermometer.

The nights were horrible. The doors were locked and the people simply could not contain their natural needs any further. A severely ill man in our car evacuated into his eating bowl, and in the darkness he wandered around with his full bowl, trying to reach the hatch of the car. The women screamed because he kept stepping on somebody all the time. Nobody dared remove his shoes, since one never knew what kind of unpleasant surprise the night might bring. Ilse and the children were completely curled up on top of what little luggage we had, so that in case of need, everything would be handy. Stefan and Marion could have been an example for the whole car. They were little heroes. Never a world of complaint. No tears. They suffered quietly through their sleepless nights.

Partly we had to thank the beautiful weather for the fact that no higher count of sicknesses broke out. But other horrors were lying in wait for us. Suddenly airplane formations appeared on the horizon – Americans. Like birds of prey, they attacked our train, assuming it to be a troop transport. At roof level they strafed all cars. I yelled to our people to lie flat on the floor, face down, hands folded in the nape of the neck. Despite the short duration of the attack, it seemed endless. The planes left and I told everybody to rise. Stefan remained lying down. My heart stopped; I thought he had been hit, but one second later, he, too, got up. That one second seemed to me like hours, even today.

The planes returned. Another attack on the train. Twenty-five hundred people, except for six hundred severely ill, jumped out of the car in panic, seeking safety on all sides. Marion was crying and shaking with terror; Stefan was pale as wax but very calm. With both children, we ran cross-country, further and further, no matter where to. Through a backyard we reached a small farmhouse. The children could not even eat the bread the people gave them and hid this wealth under their filthy coats. As if by a miracle, this attack had not caused any casualties. The following train, however, also from Bergen-Belsen lost forty-five persons.

The journey continued in the direction of Berlin. On the way, we stopped at a small station. On the opposite tracks stood a German armored train of the anti-aircraft defense. Driven by unbearable hunger, our people dashed for the field kitchen attached to the train, begging for some food. No success! I crawled underneath the train to the opposite side where nobody was standing. The cook, diverted by the begging masses, did not see me. I stole a can of "K" rations, about two pounds in weight, contents unknown. Back to our train. Secretly we opened the can – meat. Ilse, happy and proud of her thief, and the enthusiastic children kept staring at the loot.

This was a find that today could not be compared even to a shipload of foodstuff. We felt like eating everything right away. Reason, however, and many years of experience warned us, and we rationed it carefully.

Slowly we became aware of the fact that the war had reached its climax. Seven miles behind us were the Americans, as I learned from a railroad worker. We were approaching Berlin-Lichterfelde. At four in the morning, the train came to a stop. As was my habit, I went looking for loot, an old filthy pillow cover under my jacket and an eating bowl in my pocket. After having crossed many tracks, I got to a German food commissary. We had torn off our Jewish stars a few days before and the SS, feeling slowly but surely that their days were numbered, ignored us.

"Do you have anything to eat?! I asked the Red Cross nurse on night duty. "Who are you?" "I am a refugee." "The kitchen is not working yet, we only start at seven o’clock." "Don’t you have anything at all to eat?" "Well, some cold macaroni with ham, but you can’t eat it like this; it has to be heated up first."

You can image how enthusiastically I accepted even the cold food. After having filled my belly so that the macaroni almost came out of my nose, I filled my bowl, too, in order to bring it to Ilse and the children.

This, you see, was our proven procedure. If I ate first, whatever the bowl would hold could be left for my loved ones. Radiant with happiness about the wonderful meal, I ran back to the train – which had left. As if I had been hit over the head, I stared at the lonely tracks, blaming myself. For years, I had never been separated from my family, and now I should lose them like this! For an hour I stood motionless. But the train was gone. What was there to do? I left the freight station and stopped a bus that was going in the direction of Berlin. The driver took me along into the city.

Imagine this – a Jew, a bum, in rags, filthy, without a single cent, without identification papers, in Berlin – a few days before the city was stormed by the Russians. A gigantic heap of rubble. Excited masses of people. Like a beggar I stood in front of an inn. A passerby spoke to me. I told him I was hungry. He took me with him to the inn and ordered food and even beer. Slowly the terrible shock that I had endured with the leaving of the train lessened. I returned to the freight station, Lichterfelde, like a criminal who is driven again and again to the scene of his crime.

I did not trust my eyes; there was a long freight train filled with Jews that was en route from Bergen-Belsen also to the east. Onto the train I went, fervently hoping to once more reach my wife and children. The train kept rolling for hours. Finally, at four thirty in the afternoon, it passed, at high speed, through a small town – and I just caught a glimpse of Ilse, waving to me from her train that was standing still.