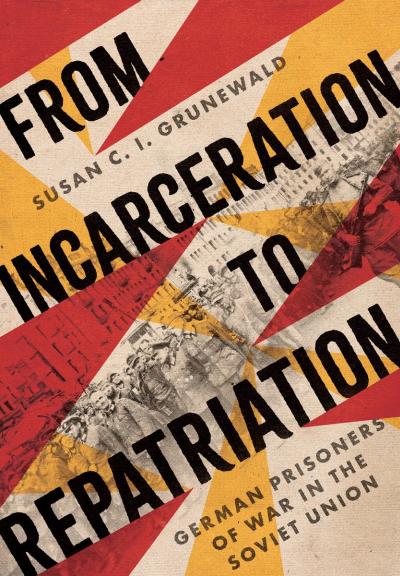

| Title: | From Incarceration to Repatriation - German Prisoners of War in the Soviet Union |

| Writer: | Grunewald, Susan C. I. |

| Published: | Cornell University Press |

| Published in: | 2024 |

| Pages: | 258 |

| Language: | English |

| ISBN: | 9781501776021 |

| Review: | Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich was destroyed by the battles on the Eastern Front. There, the Wehrmacht and SS divisions suffered the heaviest losses, and there the military strength of Nazi Germany was broken. In Eastern Europe, the Nazis also committed their gravest crimes, not only against Jews but also against other Polish and Soviet civilians. In the first year after the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, when Operation Barbarossa still seemed poised for grand success, the Wehrmacht captured huge numbers of Soviet soldiers (estimated at around five million). Horrific crimes were also committed against these prisoners of war – around three million of them perished due to murder, deliberate neglect, and starvation. As the tide of war turned, an increasing number of German soldiers fell into the hands of the Red Army. By the German surrender in May 1945, there were about 3.2 million of them. While there was no mass murder of these prisoners, many German soldiers died in captivity due to malnutrition, disease and exhaustion. The captured Germans were treated harshly, were systematically used as forced laborers (except for officers), and often spent a long time in captivity – the very last prisoners of war only returned to the Federal Republic of Germany (and the GDR) in early 1956. Young American historian Susan Grunewald has written an important book on German soldiers in Soviet captivity, using both German and Russian archival material (the talented Grunewald is proficient in both German and Russian). The relevance of this study lies in its detailed reconstruction of the Soviet Union’s system of detention and the underlying policy objectives. In the first months after the German surrender, large numbers of prisoners were released, followed by a second wave of releases in 1946 and 1947. The release of the remaining prisoners was postponed from the spring of 1947 onwards. Grunewald argues that the (long) retention of German prisoners of war was not primarily driven by a motive of revenge for what Nazi Germany had inflicted on the Soviet Union, but was mainly related to the overriding necessity of rebuilding the devastated country, with the manpower of the many prisoners being urgently needed. This perspective also led – somewhat surprisingly – to the fact that German soldiers were generally adequately fed. Grunewald notes that many German prisoners of war received better food in some periods (e.g., during the 1946 famine) than the average Soviet citizen. She also shows that this policy underwent various changes over time – not only due to shifts in Soviet leadership (after Stalin’s death) but increasingly from 1948/1949 due to the outbreak of the Cold War. The fate of the German prisoners of war became part of international politics. Grunewald correctly points out that this has essentially remained the case in the relationship between Germany and Russia to this day, with the issue now logically focusing on information about the numerous missing Germans and the locations where they are buried. For the Soviet leadership, the last German prisoners of war at the end of the 1940s became a bargaining chip in the pursuit of a Germany that, in the long run, might eventually be reunified, but in any case, should not be part of a Western bloc against the Soviet Union led by the United States. The Soviet Union failed in this (the Federal Republic joined NATO), which led to delays in the release and repatriation of the German prisoners of war. In a very interesting part of her book, Grunewald reconstructs how the uncertain fate of German prisoners of war also influenced the social and political relations in the GDR and complicated its relationship with the Soviet Union. As a loyal satellite of the Soviet Union that wanted to present itself as an ‘antifascist alternative’ to the Federal Republic, it was very difficult for the GDR government to openly advocate for the release of German prisoners of war, especially when those who were still detained in the early 1950s were labeled as ‘war criminals’ by the Soviet authorities. However, the GDR leadership also faced pressure from its own population, who continued to inquire about the fate of sons or husbands who were still being held in the Soviet Union or had gone missing there. A factor in this was that practically every GDR citizen was able to stay informed about news from the Federal Republic. Thus, the initiatives undertaken by the Federal Republic did not go unnoticed by GDR citizens. It came as a shock to the GDR leadership that they were not involved in the agreements that Soviet leader Khrushchev made with Chancellor Adenauer regarding the release of the last German prisoners of war during Adenauer’s visit to Moscow in 1955. The international-political aspects are among the most interesting parts of this highly documented study by Grunewald, which is primarily a policy reconstruction focusing on the extensive system of locations and involved organizational units in the Soviet Union. The book is less about personal stories and the individual experiences of German prisoners of war. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Article by:

- Jan-Jaap van den Berg

- Published on:

- 15-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!