Introduction

When we use the term razzia, we usually think of the German occupier's hunt for Jews or the mass roundup of men for forced labour. However, several razzias have also taken place in retaliation for acts of resistance. The most notorious of these was the one in the village of Putten, but there have also been other razzias where large numbers of (young) men were arrested as hostages for that reason.

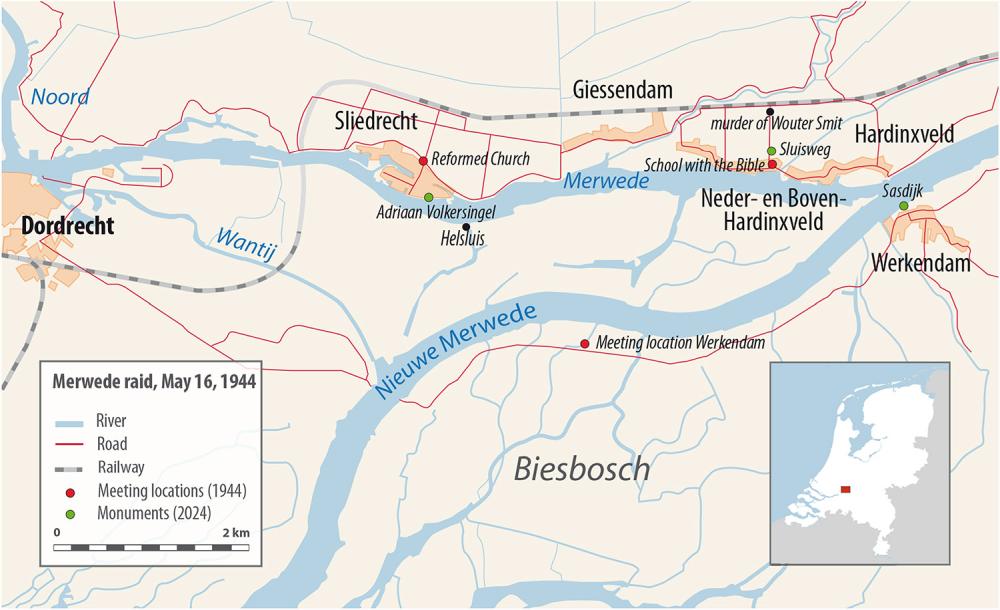

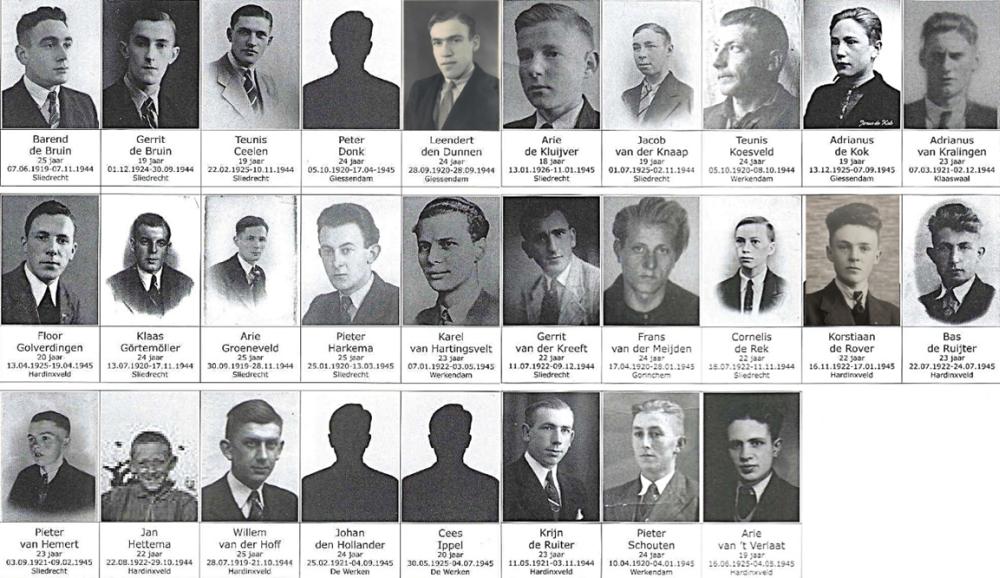

One of those roundups took place on May 16, 1944 in the river area of the Beneden- and Nieuwe Merwede across the borders of the provinces of South-Holland and Brabant. In retaliation for the shooting by the resistance of two Landwacht police officers, around 600 young men between the ages of 18 and 25 were arrested the same day in the villages of Giessendam, Hardinxveld, Sliedrecht and Werkendam and taken to Camp Amersfoort. About half of them were later transported to Germany as part of a larger group. They ended up in camps where conditions were relatively the worst and 28 of them died under appalling conditions in either these camps or shortly after returning home.

This roundup and its victims have gone down in history as The Merwede Razzia and The Merwede Hostages respectively. They provide an example of the far-reaching consequences that acts of resistance sometimes incurred and how long they continued to have an effect after the war.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- razzia

- Organised round-up of a group of people. This could be Jews but also persons in hiding or other groups.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The cause

The murder of Wouter Smit

In the evening of April 14, 1944, 57-year-old baker's assistant Wouter Smit, who was on his way home, was shot dead by a Landwacht policeman near the railway station of Giessendam.

The Dutch Landwacht was a paramilitary organization, established in 1943 by the NSB and which served the occupying forces as a kind of auxiliary police. They were subordinated to the SS and notorious for their brutal actions.

At the railway crossing there were four Landwacht policemen who had been instructed by their commander to check identity cards of passers-by. When Wouter Smit passed the first policeman, he continued walking and allegedly did not respond to the command "Stop Landwacht". This particular policeman, the 17-year-old Joop Westdijk from Sliedrecht, then shot Wouter Smit in the back without any further warning. Bystanders took him to a nearby coffee house but failed to stop the bleeding and when the doctor arrived, he had already died.

It is a mystery why Wouter Smit did not respond. It was said he was somewhat deaf, but according to his son Piet, who was 15 years old at the time, his father was not deaf at all but more likely happened to be lost in thought at that fatal moment. The last thing Wouter Smit managed to say was ‘I didn't hear it’

This brutal murder caused great dismay and indignation among the people of Giessendam and surrounding villages and when Wouter Smit was buried on April 19, many citizens walked behind the funeral coffin in a show of silent defiance.

Revenge, the shooting at the Helsluis

After the murder, the population wondered whether the resistance would retaliate. The KP Sliedrecht was furious about Smit’s murder. For some time now, people had been angered by the rude actions of the Landwacht and, moreover, Joop Westdijk's father was a widely hated man. He was also a fanatical member of the Landwacht and lived with his family in the house of the deported Jewish family Den Hartog. Westdijk already acted on behalf of the occupier as Verwalter (agent) of Den Hartog and after the deportation of the family in 1942, he bought their house and the shop from ANBO (The General Dutch Management of Real Estate), charged with the sale of real estate stolen from Jews. So, the KP was certainly keen to teach the Landwacht a lesson.

On the night of May 9 to 10, 1944, a firefight started between members of the KP Sliedrecht and the Landwacht at the Helsluis – a river lock and today a national monument that still provides access from the Beneden Merwer river to the Biesbosch tidal area. This event - as would soon become apparent - had disastrous consequences for the population of the surrounding villages.

The resistance from Sliedrecht had received information that the Landwacht would look for people who were hiding in the Biesbosch area that night. The lock keeper of the Helsluis and the farmer Kadijk - whose farm was close to the Helsluis and where people in hiding regularly stayed - had been informed in advance that this action would take place. They were also aware that the KP would be waiting at the lock for the Landwacht. The son, Rent Kadijk, who was 12 or 13 years old at the time, later said in an interview that his father had warned of the possible consequences and was therefore opposed to this scheme.

That night, six members of the KP Sliedrecht waited in their canoes at the Helsluis for the arrival of the Landwacht. When they had not appeared around 1 a.m., they prepared to return home. At that moment the boat with the officers arrived and entered the lock. The encounter in the lock chamber resulted in a shooting. On the Landwacht’s side, Westdijk Sr. (the father of the young policeman Joop Westdijk) from Sliedrecht and Okkerse from Hardinxveld were seriously injured and both died a day later. Two of the KP members were also injured. Sometime later they knocked on the door of Kadijk's farm from where they were picked up the following day. The others managed to escape and returned to Sliedrecht in their canoes or by swimming.

Various stories are circulating about the extent to which this action was really intended as revenge and especially whether it was provoked and planned by the resistance by spreading false information. The generally accepted view is that this was indeed the case and that the Landwacht policemen were deliberately lured into the trap.

In 1994, one of the resistance members who had been involved in the shooting told his story for the first time, which he had recorded by the Historical Society of Sliedrecht.[1] According to his version, it was only intended as a response to the Landwacht's plans to arrest people in hiding. However, Anja van der Starre from Sliedrecht, who conducted a lot of research into the roundup and its consequences, writes in the preface to her booklet Merwedegijzelaars (Hostages of the Merwede) that this claim can be refuted on the basis of facts. The others involved have consistently remained silent about the event and carried the truth to their graves.

Understandable perhaps, but the decision to seek an armed confrontation was a huge risk. A few weeks earlier, assaults in the towns of Beverwijk/Velsen-Noord and Groningen had already resulted in major razzias and the taking of hostages; the repression by the Germans increased every day. After all, the question was not if, but how the Germans would respond.

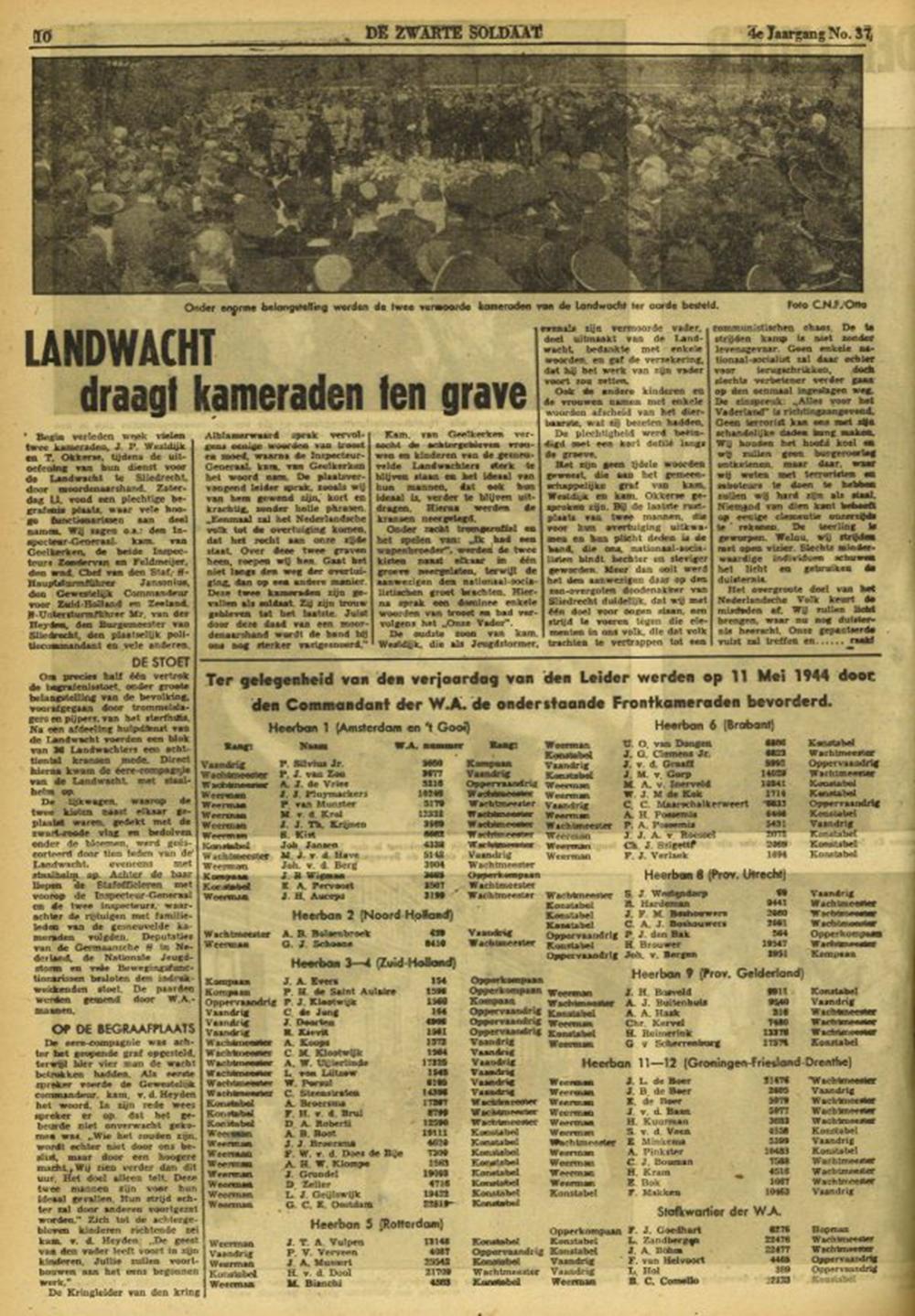

The funeral of Westdijk and Okkerse

On May 13, Westdijk and Okkerse were buried in Sliedrecht with much NSB display. Numerous prominent representatives of the NSB and the Germanic SS were present at the funeral, including Inspector General of the Landwacht Cornelis van Geelkerken and Henk Feldmeijer, the leader of the Germanic SS in the Netherlands. This indicated how serious the matter was taken. Meanwhile, there was a tense atmosphere in the region. Hardly anyone mourned the death of the hated Landwacht officers, but what would be the reaction of the occupier? Immediately after the shooting, people had already been rounded up as hostages and what was to follow next? The NSB weekly magazine De Zwarte Soldaat (The Black Soldier) quoted the following from Cornelis van Geelkerken's speech:

No terrorist can frighten us with his shameful actions. We will keep a cool head and do not intend to spark a civil war, but when we know we are dealing with terrorists and saboteurs, we will be as hard as steel. No one on that side can count on any leniency from us. The die has been cast.[2]

This statement did not bode well!

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The reaction

21 men are arrested

The Germans were furious about the death of their accomplices and especially because the perpetrators had managed to escape. As early as May 11, a total of 6 men were arrested in Giessendam and 4 in Hardinxveld (then separate municipalities), respectively. A few days later, on May 16, another 11 mostly older men from Sliedrecht were arrested. The choice of each of the individual men was not entirely coincidental. A notorious NSB member from Sliedrecht had given the Germans a list of names of people known as "anti-German" or whom he personally disliked.

The arrested men were taken to the headquarters of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD German security police) located at the Heemraadsingel in Rotterdam and, after being interrogated, transferred to the police prison on Haagseveer. A few days later they were incarcerated at the River Police at Parkhaven.

On June 13, they were woken up early and the remaining group of 20 men (one had meanwhile been released for health reasons) were transported by train to concentration camp Vught. Even though – as hostages - they were incarcerated without formal charges, they endured a tough time in Vught. In a statement published shortly after the liberation they testified about their experiences in the camp.

Upon arrival, they received the same treatment as other prisoners. They were shaved and had to wear the striped camp clothes. Every day there were long roll calls, little food and of bad quality and 6 days a week of heavy labour in the aircraft scrapyard where they were beaten for the slighest thing by the kapos. As an example of the traumatic events, the survivors also described how during the final weeks prior to the evacuation of Camp Vught, the blasts of the firing squad were heard every day at the execution site after which prisoners counted the single shots from the firing squad leader as he made sure each of the executed was dead. Due to the approaching Allies, the camp was evacuated on September 5 and 6, 1944 and the almost 3,500 prisoners were transported elsewhere; the men went to Sachsenhausen and the women to Ravensbrück.

The hostages from Giessendam, Hardinxveld and Sliedrecht were not officially released yet, however, and had to remain in the camp for a while longer. During the night of September 13, they were transported to Camp Amersfoort in cattle wagons, where they were finally released on September 19 through mediation and at the insistence of Mrs. Loes van Overeem of the Red Cross and returned home.

The razzia of May 16, 1944

The taking of 21 hostages proved not to be enough for the Germans. The KP members responsible for the shooting had not come forward. In the early morning of May 16, between 2,000 and 2,500 troops from the Grüne Polizei (nickname, due to their green uniforms), the SS and the Wehrmacht, assisted by the Landwacht, were assembled in the villages on the Merwede. They closed off Giessendam, Hardinxveld, Sliedrecht and Werkendam and went chasing for young men between the ages of 18 and 25.

No one in that age group was safe. Men who were often on their way to work early were arrested on the street. Houses, trains and buses as well as the surrounding polders were thoroughly searched. A few men managed to hide successfully, but hundreds were taken to the assembly points.

Years later, various testimonies about the razzia were recorded. This is what one of the men said about his arrest:

In May 1944 I lived with my pregnant wife and son on the Rivierdijk in Sliedrecht, close to the water-tower. On Tuesday, May 16, I cycled with Kees E. to the Lanser shipyard on Baanhoek, where we both worked. On the way, near the Grote Kerk, we encountered the daughter of our boss Gerrit Lanser who told us to get out of there because a razzia was taking place. We then immediately turned around. Kees knew of a hiding place, but I preferred to return back home. Unfortunately it turned out that I was not safe there, because some time later the door was kicked open in and I had to go with them. This happened despite the fact I had an Ausweis which should have exempted me from employment in Germany: I had been rejected during a previous inspection among Lanser employees for employment in German. I was taken to the Dutch Reformed Church in Sliedrecht, after which the journey continued via Baanhoek to Hardinxveld, where the Protestant school’s playground served as a point of assembly. Late that evening, all the young men were loaded into police vans and taken to Amersfoort.

The places where the men were assembled were in Sliedrecht at the Dutch Reformed Church, in Beneden-Hardinxveld on the playground of the protestant school on the Rivierdijk and in Werkendam at the forge of Jaap de Kreek on the Bandijk. Parents, wives and other relatives tried to speak to their kin and slip clothing, food or other things into their hands. The Germans did not allow this and brutally kept anyone at a distance who tried to do so. In total, approximately 600 young men were arrested that day within the four municipalities and in some cases elsewhere.

After sometimes having spent a day at the assembly points, the first group left in the early evening in trucks for Camp Amersfoort, as it turned out. A second group left around 21:00 with the same destination.

Definitielijst

- Ausweis

- Ausweis: a specific work permit ID, issued by the German occupation authorities, which stated where exactly where and when one was authorized to work.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Grüne Polizei

- Green Police, nickname – due to their green uniforms – for the Ordnungspolizei (Order Policy) and which is the common denominator for local policy units tasked with exercising regular policy responsibilities during Nazi-Germany from 1936 to 1945.

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- razzia

- Organised round-up of a group of people. This could be Jews but also persons in hiding or other groups.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Captivity

Camp Amersfoort

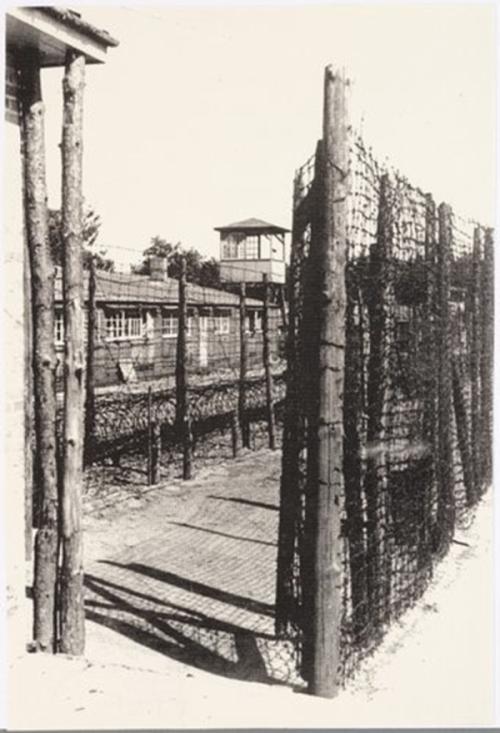

During the first days in the concentration camp, the Merwede hostages were left in relative peace. As hostages in Amersfoort they were treated somewhat milder than the other prisoners and receiving Red Cross packages on Fridays was a welcome addition to the meager and bad food. After a few days, work needed to be done, and they were assigned to the straw- and rush-weaving workshop. They did not have to appear for a rollcall until June 9, more than three weeks after arrival.

These rollcalls, often lasting hours, were a real torment and other bullying and maltreatment also occurred on a daily basis.

In addition to the men from the area around the Merwede, there were also other hostages in Amersfoort. Since April 16, a group of men from Beverwijk/Velsen-Noord had already arrived, and on April 25 another group had arrived, this time from Groningen, Bedum and the surrounding area. These men had also been arrested during razzias in retaliation for resistance actions. In Beverwijk and Velsen-Noord the razzia was a response to several liquidations by the resistance and in Groningen to the shooting and killing of a police officer. Whilst this article is primarily about the Merwede razzia and hostages, it largely applies to these men as well. They ultimately suffered the same fate.

The men had been captured as hostages and would be held until those responsible came forward. This did not happen, but most likely this was also an empty promise and the transport to Germany would have taken place anyway.

In a 2005 interview with the Brabants Dagblad, the son of a Merwede hostage recounts what his father experienced in Amersfoort:

The horrors of Camp Amersfoort stuck in my father’s mind all through his live. In particular, the Rose Garden of SS officer Kotälla haunted him in his nightmares. Kotälla took great pleasure in mistreating prisoners and the Rose Garden was his invention: an elongated punishment place with a sand surface and surrounded by poles connected with barbed wire. Prisoners were forced to stand still in the Rose Garden for 24 to 48 hours without any food or water.

As early as May 19 and in subsequent weeks, many of the arrested men were released. In most cases this happened at the request of their employer. There were many shipyards and other companies in the region, such as the 'Aviolanda' aircraft factory, that were important to the Germans and where they could not be missed. An estimated 250 men were released in total, but an exact record of who was arrested and/or released no longer exists.

On June 28, 1944, the remaining Merwede hostages, together with those from the IJmond region and Groningen, were earmarked for transport to Germany. They had to send a pre-printed note to their relatives asking them to provide a suitcase with clothes and toiletries. The suitcase was not allowed to contain any food, money, letters or identity papers and had to be handed in at the Public Employment Office in Amersfoort before July 5. The family did not get an opportunity to see or speak to their relatives. During the night of July 6 to 7, 1944, the men had to arrive at 02:30. Then they had to walk with their suitcase to the Amersfoort railway station. At 04.30 the train with regular passenger carriages containing 624 hostages left the Amersfoort railway station for Germany.

The suitcase of Gerrit Verhoeff, on display at the memorial centre of Camp Amersfoort. Source: Jan de Jager

Germany

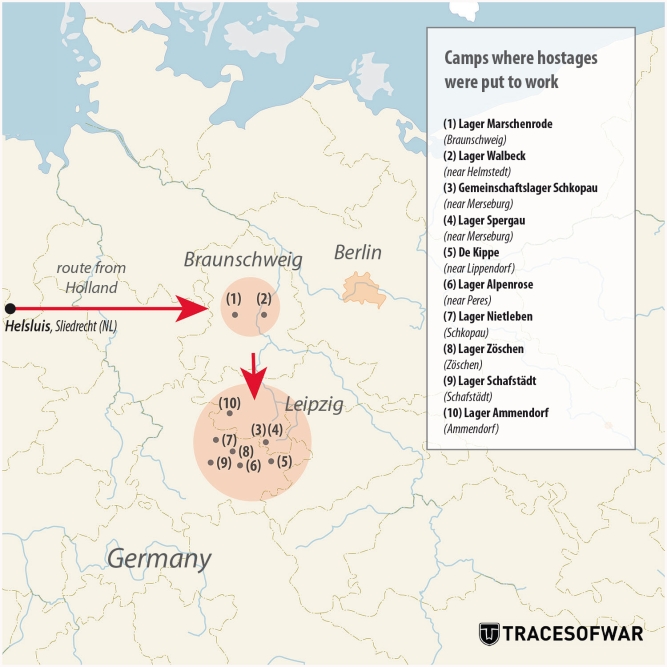

The first stop in Germany was Braunschweig where the devastation caused by Allied aerial bombings was clearly visible. The men whose surnames started with the letters S to Z had to get off here and the train continued with the other hostages via Magdeburg to Halle and further to Schkopau near Leipzig.

As far as is known, they ended up in the following camps (in German: Lager), all located in central and eastern Germany:

- Lager Marschenrode in Braunschweig

- Nieder Walbeck north of Helmstedt

- Gemeinschaftslager Schkopau and Lager Spergau near Merseburg

- Die Kippe near Lippendorf

- Nieder Alpenrose near Peres

- Nieder Nietleben

- Nieder Zöschen

- Lager Schafstädt

- Nieder Ammendorf

Most of the hostages were held in several of these camps. Some other hostages were held in other camps.

The locations of the camps where the Merwede hostages were employed. Source: Bert Heesen, TracesOfWar

In the 'regular' Arbeitseinsatz, the men (but also women) involved usually fell under the responsibility of the companies where they were employed and they also enjoyed a limited degree of freedom outside working hours.

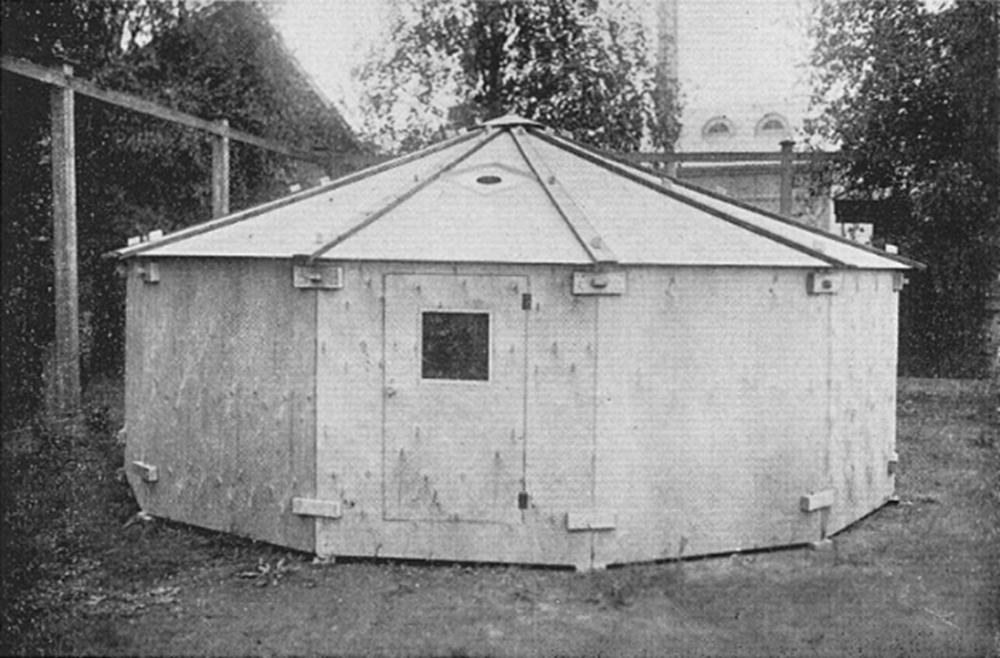

However, the Merwede hostages had to deal with a completely different regime. They were locked up in camps and in most cases these were so-called Arbeitserziehungslager or work education camps. In these types of camps, it was mainly men who had either backed out or escaped from the Arbeitseinsatz that were imprisoned for 're-education' purposes. The conditions were reminiscent of those in the concentration camps. Housing was usually awful, it was generally squalid and filthy, hygiene was lacking and the food and medical care were severely inadequate. Disease and maltreatment were commonplace and there was always a latent risk of becoming a victim of Allied bombings. The factories where they worked were regularly targeted by bombers and often there were either no bomb shelters or prisoners were denied access to these.

The Third Reich had an insatiable hunger for workers who were then deployed for a wide range of tasks. This happened, among others, at the factories of BUNA (Butadiene Natrium), Brabag (Braunkohle Benzin AG) and ASW (Aktiengesellschaft Sächische Werke) where synthetic gasoline and rubber were produced from brown coal.

They were also deployed in (former) salt mines, where engine and aircraft parts were manufactured hundreds of meters underground, or put to construction work or to clear the rubble after Allied bombing or shelling.

Working days lasted 12 hours or more, after which they still had to undertake the return journey to the camp - often on foot. Men fell ill and weakened visibly; it obviously didn’t take long before the first lives were lost. Leendert den Dunnen from Giessendam was the first hostage to die; on September 28, 1944. That day was his 24th birthday.

Later, a Merwede hostage from Werkendam recounted his time in Germany in an interview:

During the night of July 6 to 7, 1944, the Germans deported us to Germany. We were very anxious, because we had no inkling what lay ahead of us. Groups were deposited in various places. Our team fell apart in Brunswick. Piet Schouten from Werkendam died there. We had to spend the night in the future SS camp Schkopau. There they selected the construction workers among us. After we had completed the construction of the camp, we were transported to Böhlen in cargo carriages. There we were put to work at ASW, a factory for synthetic fuels. Our housing in Lippendorf was miserable. Our camp consisted of cardboard huts situated on a hill fenced off by barbed wire. We slept under a single blanket on the naked soil and only had one small tap at our disposal. We had to relieve ourselves in a hole inside the forest. We were barely fed and had to make do with one cup of tea during 14 hours of factory work. We walked back to our camp at, 18:00 totally exhausted. Some Germans in that factory were very cruel. They jeered at us. One of them hit my neighbour Jantje Baelde as hard as he could. There was also often severe beatings in the camp. Many people died.

In November 1944 we were transferred to a camp near Peres. There were twelve of us lying on bunk beds in a single room. We had to dig trenches for water pipes. The food was bad again. A total of 130 people died from malnutrition, exhaustion and other misery. Among them was Cees Ippel from Werkendam.

In order to get hold of food, we took any chance. Brother Co nicked a canister of food. He received a tremendous beating. Thanks to my foreman Schluss, a good guy, I never received any blows from the Germans.

The journey back and homecoming

During April 1945, the first group of hostages were liberated by the advancing Allied armies. Many of them were sick and/or malnourished and only after medical care or nursing they could attempt to return home.

The journey home was not easy because there was hardly any means of transportation available. Sometimes they could ride on buses or on trucks, but others came home on foot and by hitchhiking or even on a stolen bicycle, often taking long detours.

The reception at the Dutch border was often formal and unfriendly. Among the thousands of Dtuch people who returned from Germany there were also collaborators and the wheat had to be sifted from the chaff. One such returned hostage tells how the old German army jacket he was wearing and some German Marks were ruthlessly taken from him.

In the course of June 1945, most hostages had returned home and by then some sad conclusions could be drawn. Of the total group (including the hostages from Groningen and North-Holland) that had been transported on July 7, 1944, approximately 100 appeared to have died.

Of the Merwede hostages alone, there were 26 deads of which 2 died a few months after the liberation from the effects of tuberculosis they had contracted in Germany.

Many surviving relatives were not even aware at that time their son or husband had died. They sometimes only learned this from returning hostages whereas the official death notifications from the Red Cross often only arrived months or more after the liberation.

It is known where most of the hostages who died are buried. With the assistance of the Dutch War Graves Foundation, 15 of their remains (or their ashes) were later reburied in their own hometown or on the Dutch War Cemetery in Loenen. One hostage is buried at the Dutch War Cemetery in Osnabrück and one rests in a communal grave at the public cemetery in Müglen. The names of 7 hostages appear on the Ehrenmal in the park at the former cemetery of Zöschen. In Peres-Lippendorf and Zöschen, among others, monuments commemorate the Dutch who died there.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- razzia

- Organised round-up of a group of people. This could be Jews but also persons in hiding or other groups.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

After the war

After home coming

After returning home, the men had to try to get their lives back on track. Reconstruction of the ruined country took precedence and there was little room for discussing past events. They started a family and/or threw themselves into work and tried to put the painful experiences behind them or suppress them altogether.

This seemed to work in many cases, but often it was only pretence. The people in their immediate surroundings noticed all too often that something was wrong. Many men appeared to have changed upon their return; they were more often edgy, easily irritated and emotionally less receptive. This also played a role in family relations and many wives and children were directly faced with the psychological and sometimes physical consequences of the war. Asking for help was not the way to go about it, that was unthinkable and, moreover, it was hardly available.

These war experiences have taken their toll on many families. The diagnosis of PTSD is of a later date, but it is evident that many ex-hostages suffered from this condition and had to deal with it.

Later, some family members mentioned the following:

We have no photos, no data, nothing at all from the war period. It was never talked about either. From the age of five or six, my father-in-law had been friends with Pleun den Uil, who had also been arrested. The friendship was for life. The only time it was being discussed was during the 1970s when the Breda Three were to be released from prison, and all of the memories (and hatred) came flooding back. A holiday (32 years after the war) in the Black Forest, Germany, turned out to be traumatic for him.

My husband was arrested when he made his way home after having taken children to their school. He drove a horse-drawn carriage. I gave him a change of clothes before he left.

When he came back, in the summer of 1945, he looked terrible.

Our son – only one year old - obviously didn't recognize him and thought he was a strange guy. My husband had changed quite a bit when he returned.

He never told me anything about the period in Germany, except that he had suffered a lot of beatings. Later, we got another daughter and were married for almost 52 years. He passed away in February 2001.

Over the years, the razzia passed somewhat into oblivion - except for the victims. There were no monuments to commemorate and among the post-war population little or nothing was known about the roundup.

Forty years after the roundup, on April 16, 1984, the former hostages met for the first time as part of a larger group during a reunion in Beverwijk. A few days later, on April 25, there was a similar reunion in Bedum. Hostages from the Merwede area were also welcome at both reunions and this led to the initiative to organize a reunion in Sliedrecht as well. On June 15, 1985, some 100 hostages met and recalled experiences they couldn't share with others. The deceased hostages were also commemorated during a minute's silence.

During the preparations for the reunion, the idea arose to install memorial plaques at the former assembly points. The municipal authorities of Hardinxveld-Giessendam and Sliedrecht supported this idea and covered the costs of both identical bronze plaques. On June 14 and 15, 1985, the plaques on the walls of the former Protestant School in Hardinxveld-Giessendam and the Dutch Reformed Church in Sliedrecht were unveiled by the mayors of both towns. More than 100 ex-hostages were present.

2005 The Digital Monument and the period thereafter

Twenty years after the unveiling of the plaques, a website was created that acts as a second monument. The initiator was Anja van der Starre, herself the daughter of Merwede hostage Bas van der Starre who died in 1995. She developed a desire to learn more about her father's experience during the war after his death and to visit the area where he had been imprisoned.

In 2005, she visited the town of Walbeck in eastern Germany for the first time and descended into the salt mine where her father had worked 1,181 feet underground. It turned out to be an intense experience. There was already a website for the victims of the razzia in Beverwijk and surroundings and she decided to create a similar website for the Merwede hostages.

The website has become a well-organized one, with the victims of the roundup receiving the attention and respect they deserve. The site came online in December 2005 and was still far from complete at that time. The internet was not yet as fast and established as it is now, but a flood of reactions with additional information ensued partly due to the publicity in the local media. There were also responses in which people asked Anja if they could tell their own story. Evidently, the razzia continued to attract people’s interest.

Today, after years of research and conversations with hostages and their relatives, the website is the ideal place to find information about the razzia, the hostages, their workplaces and the camps where they were imprisoned. That information is provided through name lists, texts, photos and other supporting documents. However, the story is never finished. As years go by, new information continues to the urface.

In 2016, the website was awarded the offical status of 'digital heritage' by the Dutch Royal Library. As a result, the website was guaranteed to remain available and accessible for the distant future. Meanwhile, a similar website for the hostages from Beverwijk has been created, followed by one of Beverwijk, and they also received the same recognition.

Anja van der Starre's booklet 'Merwedegijzelaars' was published in 2010 and rewritten and updated in 2020 to commemorate 75 years of liberation. In order to pass on this story to the youth, Judith Brinkman (relative of a victim) wrote the booklet 'Helsluis' in 2018, specifically for groups 7 and 8 of primary education. In this booklet, the story of the razzia is narrated through the eyes of the young girl Anna. It is illustrated by Jesse Boom and encourages young individuals to contemplate the positive and negative aspects of wartime, freedom, and the (downside of the) resistance.

Well-attended exhibitions dedicated to the razzia have been on display in the Sliedrechts Museum and the Biesbosch Museum Werkendam. The story of the Merwede hostages is now well-embedded in the permanent exhibition about the Line Crossers in De Wilgenhorst in Sliedrecht.

Since 2018, Struikelsteinen Sliedrecht Foundation has laid Stolpersteine for the deceased hostages. Pictured here is the stone for Teunis (Teus) Ceelen at Stationsweg number 196. His brother Jos was also arrested but was released from Camp Amersfoort. Teus was transported and ended up in various camps. He died only 19 years old, on November 10, 1944 in 'De Kippe' in Lippendorf. On January 10, 1945, his obituary was published in an emergency edition of the local newspaper, the Merwedebode.Teus was reburied in November 1949 together with three other hostages at the General Cemetery in Sliedrecht.

In 2018, the Dutch public broadcast network NOS decided to make a TV documentary about forced labourers. They came into contact with Anja van der Starre via her website about the Merwede hostages. Subsequent discussions concluded to take the Merwede razzia and its consequences as a starting point for the documentary. Recordings were made in Hardinxveld-Giessendam, Sliedrecht and in Camp Amersfoort. The son of Wouter Smit, the bakery assistant shot by the Landwacht, and two former hostages Marius den Breejen and Kees Mijnster told their story in the documentary and Anja and Heleen van der Starre recounted their father's story in former East Germany. As part of the Remembrance Day commemorations on May 4, 2019, the documentary was aired on national television. It can still be viewed online.

As a result, the razzia in the villages returned into our collective memory, bit by bit. There was a greater need for memory and commemoration, and after the publicity surrounding the documentary, the three municipalities concluded the time had come for a genuine monument.

Upon initiatives of local politicians, a committee was formed consisting of relatives of the victims and representatives of the May 4 and 5 commemoration committees of the respective municipalities. The starting point was that there should be a monument that consisted of three associated parts, each part representing a municipality.

Local media called on local artists to register if they were interested in designing and creating a monument. Out of a total of fourteen applications, three were selected to create a design and present it to the committee.

The committee ultimately selected the design by the artist Richard van der Koppel from Genderen. He explains his design as follows:

It is an image of a young man in work clothes from the 1940s and this young man will be placed at each of the three locations. It's the same man but in different poses. In three steps he looks forward from the right over his shoulder. His fist is clenched, half open and open. The statue is placed on a pedestal and next to the statue are two empty pedestals. The statue is placed on a different pedestal for each municipality.

The monument is about loss and change and about the past, present and future. The empty pedestals symbolize the men who have not returned. The number is a reference to the three locations.

The man's posture is a reference to the statue 'The Stone Man' in Camp Amersfoort.

The relatives who were part of the committee chose to add the following words to the pedestals:

- Fear

- Innocence

- Conflict

- Sorrow

- Recognition

- Compassion

The unveiling of the monuments was to take place exactly 76 years after the roundup, on May 16, 2020, but due to the prevailing Covid measures, this had to be postponed. The three monuments were finally unveiled on October 3, 2020. Due to the newly tightened Covid measures, only immediate relatives could be present.

The monuments can be found on the Sluisweg in Hardinxveld-Giessendam, the Adriaan Volkersingel in Sliedrecht and on the Sasdijk in Werkendam.

Definitielijst

- Breda Three

- Refers to specific German war criminals convicted by a Dutch court to a life sentence in the prison of Breda. Originally there were four, but one of them, Willy Lages, was temporally released in 1966 after being (wrongfully) diagnosed with cancer. He never returned from Germany where he was operated. During the 1970s, discussions pertaining to the early release of any of the remaining three war criminals aroused a widespread and emotional public debate. In the end, Joseph Kotälla died in 1979 a natural death in imprisonment, Ferdinand Aus der Funten and Franz Fisher were released in 1989 and died soon after.

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- razzia

- Organised round-up of a group of people. This could be Jews but also persons in hiding or other groups.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Epilogue

This article explains the complexity and severity of the occupation, the types of dilemmas people faced, and the consequences of (ill-considered) actions. In a flash second, a 17-year-old Landwacht policeman shot and killed an innocent person. Maybe he wanted to act tough or tried to impress. Members of the resitance decided to take revenge. They were warned, but they did it anyway. Did they ever realize and consider the possible consequences? They likely did, but the doings of the Landwacht caused so much frustration and anger that they took this risk for granted. Parents lost a son, wives their husbands, children their fathers. The consequences of the actions of the resistance had an impact on future generations. Of the hundreds of young men who returned, their later wives and children often had to endure the aftermath of these events. Some of the resistance members who were involved in the shooting later became active as line-crosser[3]) during the winter of 1944. They undoubtedly played a heroic role in this and after the war many were decorated for it. However, a father of one of the deceased hostages later cynically said:

Prince Bernhard comes to pin medals on them, but our boy paid the price.

Today, all resistance members involved have deceased. As mentioned, they always kept silent about what had happened, but at the same time they were often just as reluctant to talk about their resistance work at large or experiences as a line-crosser.

One can only speculate as to the reason why they remained silent, but it is clear that they too had to bear the consequences of their actions until their death.

Notes

- Periodiek 56, juli 2012. Hiistorische vereniging Sliedrecht

- De Zwarte Soldaat, vierde jaargang nummer 17

- Members of the Dutch resistance who helped Allied soldiers cross the river to rejoin their units

Definitielijst

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Information

- Article by:

- Jan de Jager

- Translated by:

- Simon van der Meulen

- Published on:

- 09-11-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- BATENBURG, J.A., Sliedrecht in oorlogstijd 1940 - 1945, 1994.

- KORPEL, A., De Waard in oorlogstijd 2, De Klaroen, Alblasserdam, 1984.

- KWANT, DS G.W., Sliedrecht 10 mei 1940 - 5 mei 1945, Fa. De Waard, 1945.

- SIMONS, J., Liniecrossers, Omniboek, 2021.

- STARRE, ANJA VAN DER, Merwedegijzelaars, Historische Vereniging Hardinxveld-Giessendam, 2010.

- Interviews with, quotes and accounts by the hostages and/or their next of kin have been taken with permission either in full or in part from www.merwedegijzelaars.nl and from Merwedegijzelaars, Anja van der Starre.

- Periodiek 56 juli 2012, Historische Vereniging Sliedrecht.

- De Zwarte Soldaat, vierde jaargang, nummer 37.

- Documentaire De Merwederazzia, van gijzelaars naar dwangarbeiders, mei 2019, on the website of the NPO .

- Struikelstenensliedrecht.nl

- Razziabeverwijk.nl

- Groningergijzelaars.nl