Prologue

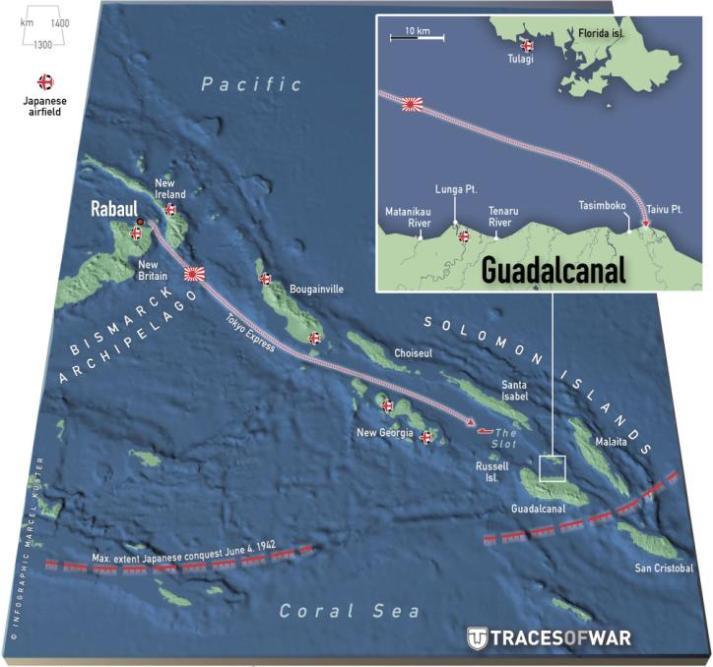

Many historians consider the Battle of Midway, fought from June 3 to 8, 1942 by Japanese and American aircraft carriers, as the major turning point of the war in the Pacific. In this battle, the US Navy did indeed achieve its first major victory at the expense of the Imperial Japanese Navy, but the tipping point had already been initiated by the Doolittle Raid and the Battle of the Coral Sea. Moreover, after Midway, Japan's drive for expansion was far from curbed. The Japanese relentlessly continued to conquer islands in Micronesia and Melanesia. Although the Allies had succeeded in averting the conquest of New Guinea, they could not prevent the Japanese from massively fortifying their naval base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain, now part of Papua New Guinea.

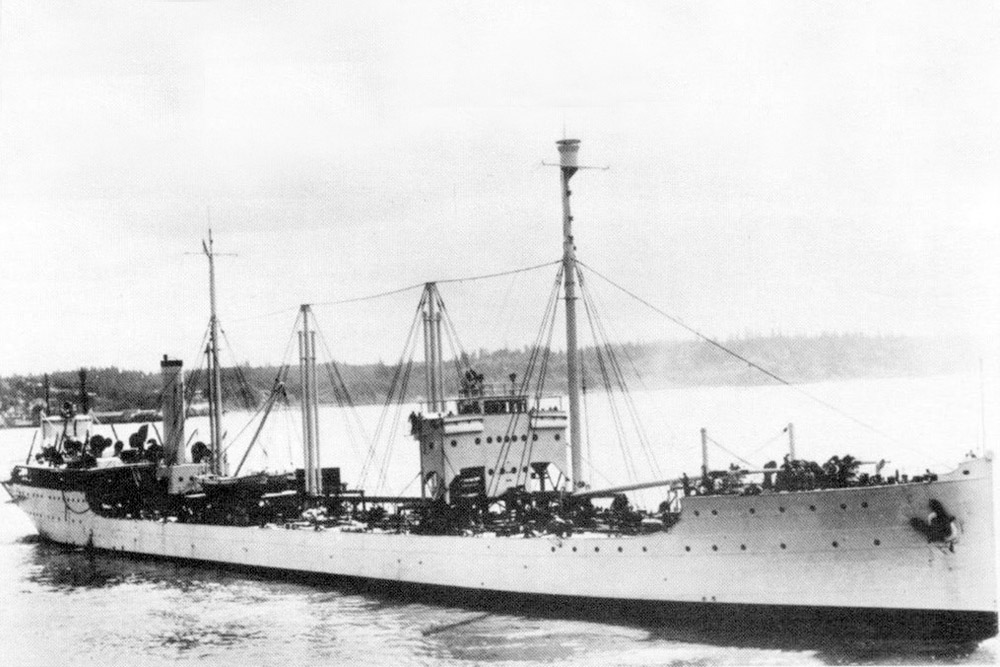

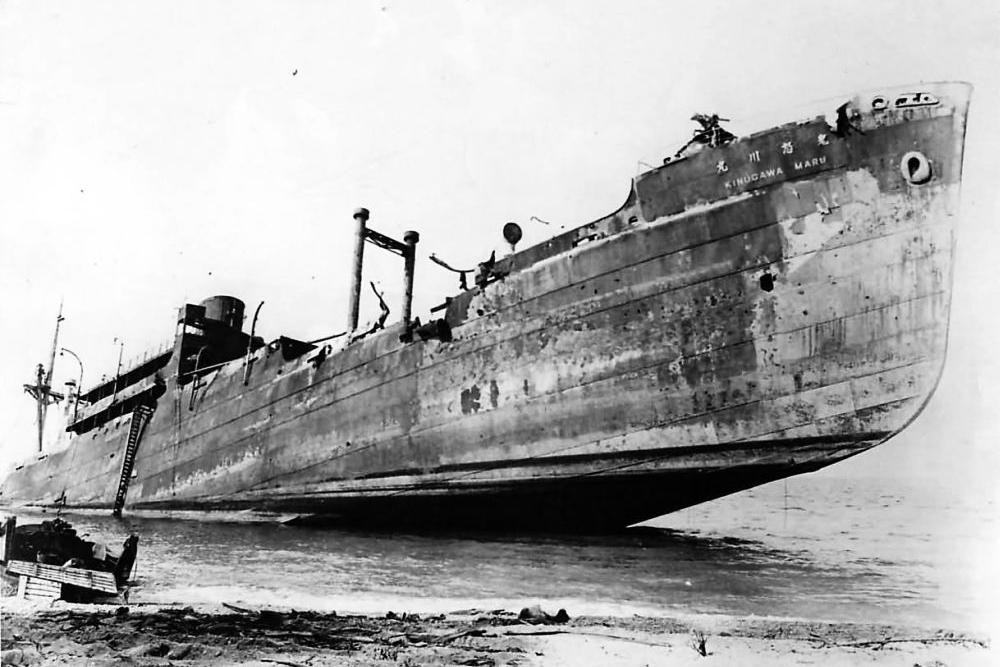

The wreck of the Japanese troopship Kinugawa Maru on the north coast of Guadalcanal. Source: World War Photos

Admiral King ordered US Marines Major General Alexander Vandergrift, the commander of the 1st Marine Division, to capture and occupy Tulagi and Guadalcanal. On August 7, 1942, 19,000 American Marines conquered the islands and the island of Florida near Tulagi without any significant issues. The Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, responded immediately and ordered a fleet of cruisers to engage the Allied amphibious forces. The Japanese achieved a major victory, putting the supplies to the Marines on Guadalcanal in great danger. This was followed by repeated attempts by the Japanese to regain control of the island and the strategically important airfield on the island, which the Americans had renamed Henderson Field. The Battle of Guadalcanal ended in a war of attrition in the scorching heat and stifling humidity of the tropical island itself while mutual supply attempts provoked several naval engagements. After the Battle of Guadalcanal, so many ships had sunk in the sea between Guadalcanal and Florida Island that it was named Ironbottom Sound by the Allies.

Although the Japanese were militarily a match for the Americans and Australians and suffered equal losses during the Battle of Guadalcanal, they were unable to recapture the island. At the end of 1942, the Japanese army and navy leadership had to admit that they had lost the battle. This gave the Allies their first land victory over the Japanese and marked the turning point in the war in the Pacific, which had started with the Doolittle Raid, the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway. After the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Japanese were forced onto the defensive. This was mainly because they could hardly compensate for their losses while the American war machine was just starting to run at full speed.

Guadalcanal The island was discovered in 1568 by a Spanish fleet led by Alvaro de Mendana de Neira. Pedro de Ortega Valencia, a subordinate commander of Mendana de Neira, named the island Guadalcanal after his native village in Andalusia. In the 18th and 19th centuries, European whalers, settlers and missionaries began to settle on the island. At that time, most of the 60,000 original inhabitants were taken as slaves to Australia. In 1893, the island became a British protectorate as part of the British Solomon Islands. In the early 20th century, Guadalcanal was home to large copra plantations run mainly by Australians. Furthermore, there were a few small villages on the sheltered north coast and along the main rivers. After World War II, tourism boomed on Guadalcanal, although agriculture and fishing remained the main economic pillars. In 1978, the Solomon Islands became an independent nation. |

Definitielijst

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Midway

- Island in the Pacific where from 4 to 6 June 1942 a battle was fought between Japan and the United States. The battle of Midway was a turning point in the war in the Pacific resulting in a heavy defeat for the Japanese.

- Raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Japanese plans and American arrangements

From late 1941 onwards, the Japanese had gone on the offensive to conquer areas rich in resources such as oil, tin and rubber. They viewed the US Navy as their main obstacle and tried to eliminate it in advance by attacking their fleet stationed in Hawaii. During the air raid on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese crippled the American Battleships but missed the opportunity to hit the American aircraft carriers because those were out at sea. Moreover, they failed to destroy the American submarine base and oil supplies at Pearl Harbor. This enabled the Americans to counterattack swiftly, leading to the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway. In the intervening months the Japanese conquered the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, Burma, the Dutch East Indies, Wake Island, the Gilbert Islands, Guam and New Britain. They established a large naval base in the capital of the latter archipelago, Rabaul. Despite the setbacks in the Coral Sea and at Midway and the failed attempt to seize New Guinea, the Japanese continued to establish the so-called defensive belt around their greatly expanded territory. In May 1942, several southern islands of the British Solomon Islands were occupied, and the conquests of New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa were planned.

Initially, the Allies only wanted to conquer the southern Solomon Islands of Tulagi and the Santa Cruz Islands, but after pilots of American reconnaissance flights reported that the Japanese were building an airfield on Guadalcanal, this island was included in the campaign. Operation Watchtower would start on August 7, 1942. In June and July 1942, the 75 Allied war- and transport ships gathered at Fiji. The fleet consisted mainly of American vessels assisted by Australian cruisers. The commander of the war fleet was Admiral Frank Fletcher, who flew his flag on the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga. The transports and their protection fleet of cruisers and destroyers were commanded by Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. General Vandegrift commanded the 16,000-strong amphibious force, which consisted largely of U.S. Marines. The Marines were armed with M1903 Bolt-Action rifles with M1905 bayonets, Browning Automatic 80-G-20683 rifles, mortars, Browning .50-cal water-cooled machine guns and hand grenades.

The troops of the 1st Marine Division could land undisturbed on the beaches of Guadalcanal. Source: Britannica

Due to bad weather during the night of August 6 to 7, 1942, the Allied invasion troops were able to approach the southern Solomon Islands unnoticed. The Japanese defenders of Tulagi and the nearby islands of Gavutu and Tanambogo were therefore surprised by 3,000 American Marines who conquered the islands relatively quickly. Almost all 900 Japanese defenders were killed in this attack because they fought to the last man. The 11,000 Marines who landed on Guadalcanal on August 7 encountered virtually no opposition. The Japanese occupation on the island consisted of some 600 engineers and construction workers and 2,200 Korean prisoners of war, all of whom fled into the hills when the Americans landed from Rear Admiral Turner's transports. The Japanese left behind all their heavy equipment and supplies. On August 8, the airstrip under construction was firmly in Allied hands. The US Marines used Japanese bulldozers and excavators to expand and complete the airfield.

Definitielijst

- Browning

- American weapon’s designer. Famous guns are the .30’’ and .50’’ machine guns and the famous “High Power” 9 mm pistol.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Midway

- Island in the Pacific where from 4 to 6 June 1942 a battle was fought between Japan and the United States. The battle of Midway was a turning point in the war in the Pacific resulting in a heavy defeat for the Japanese.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Battle of Savo Island

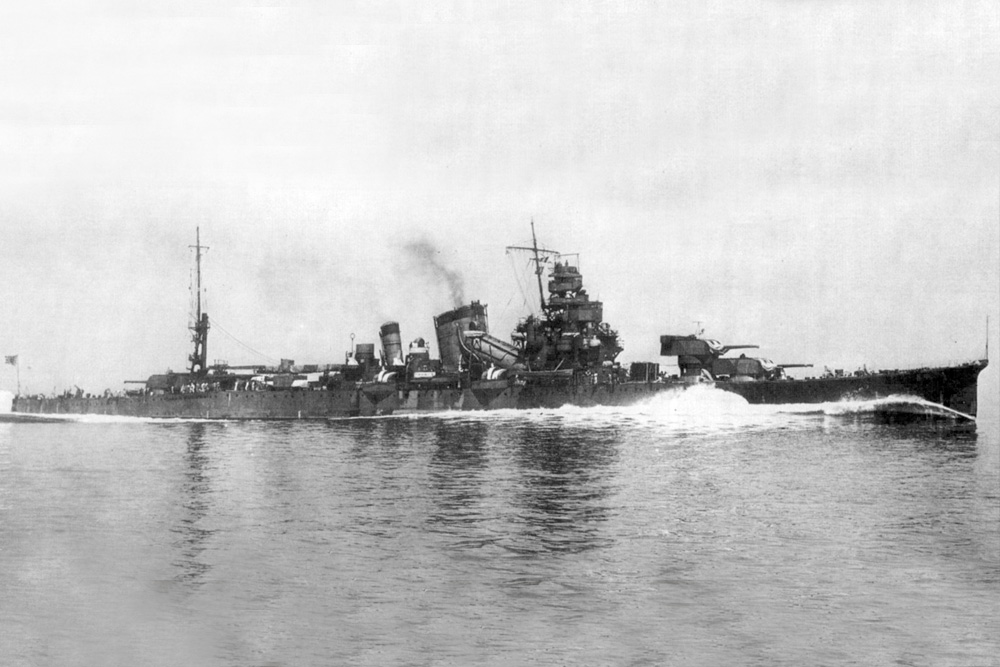

The Japanese responded to the Allied attacks on Tulagi and Guadalcanal by despatching a hastily assembled cruiser fleet. The commander of the 8th Fleet in Rabaul, Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, flying his flag on the heavy cruiser Chokai, left his base with the light cruisers Tenryu and Yubari and the destroyer Yunagi in the evening of 7 August. The 6th Cruiser Division, consisting of the heavy cruisers Aoba, Furutaka, Kako and Kinugasa, joined him. Around noon on August 8, Mikawa entered The Slot, the wide passage between the Solomon Islands, and reached Guadalcanal at night near the tiny island of Savo. The Japanese navy was the only naval force specialized in night operations and Mikawa therefore planned his attack on the night of August 8 to 9.

The heavy cruiser Chokai (1932) of the Takao class was sunk in 1944 during the Battle of Samar. Source: World War Photos

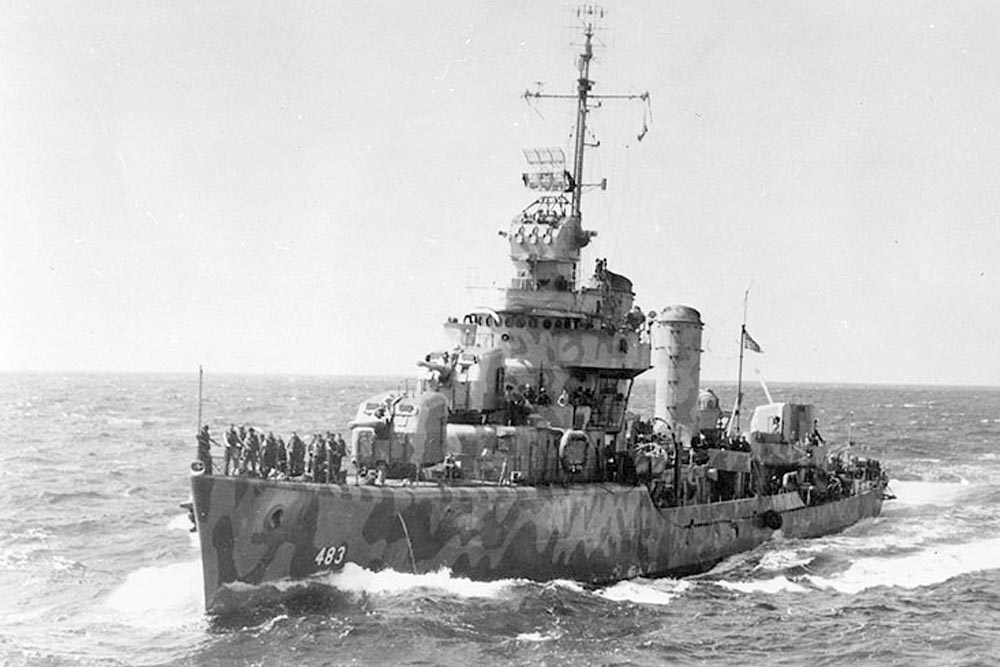

Rear Admiral Turner had divided his warships into three Task Groups. The Northern Force consisted of the heavy cruisers USS Astoria, USS Quincy and USS Vincennes and the destroyers USS Helm and USS Wilson. This fleet was located between Savo Island and Tulagi. The heavy cruisers USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra, together with the destroyers USS Patterson and USS Bagley, constituted the Southern Force, which was located between Savo Island and Guadalcanal. The light cruisers USS San Juan and HMAS Hobart and the destroyers USS Buchanan and USS Monssen made up the Eastern Force between Florida Island and Guadalcanal. The heavy cruiser HMAS Australia protected the fifteen transports at Lunga Point, where the Marines had landed on Guadalcanal. There were also eight transport ships at Tulagi. The destroyers USS Blue and USS Ralph Talbot were in forward positions to the west.

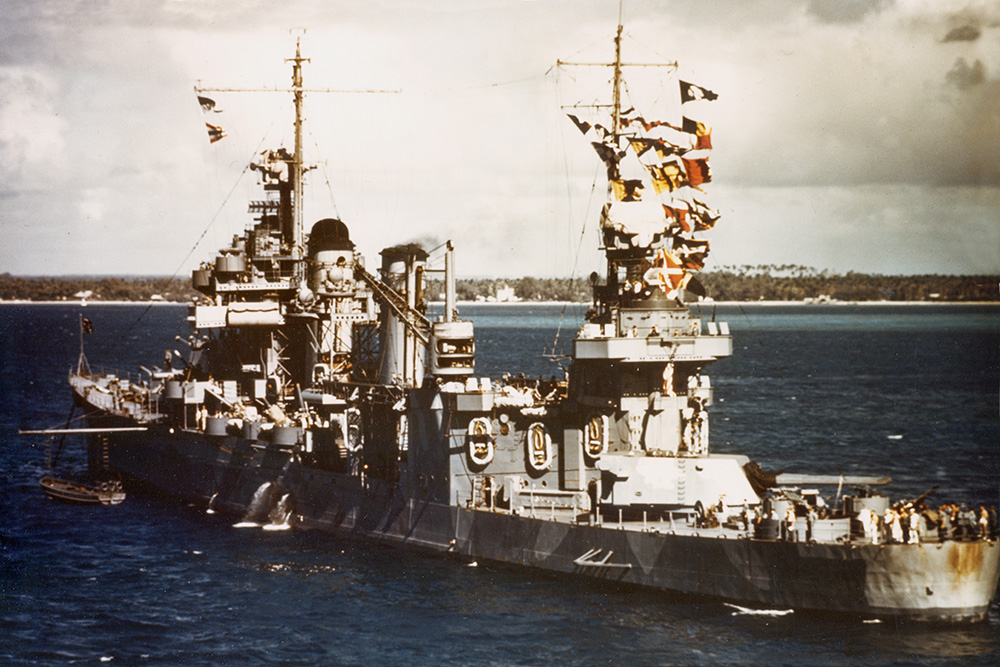

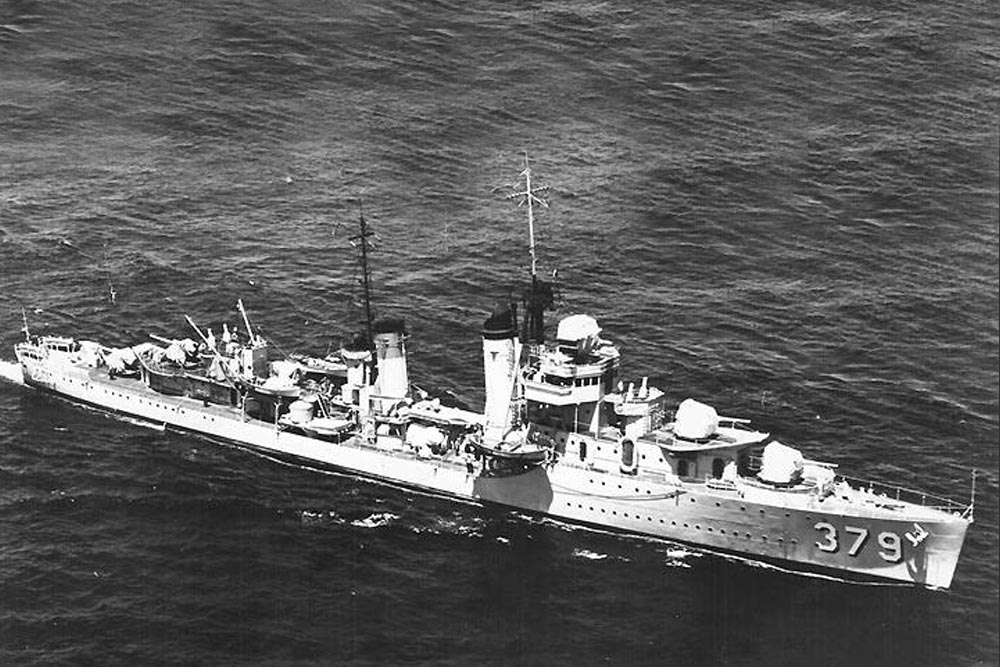

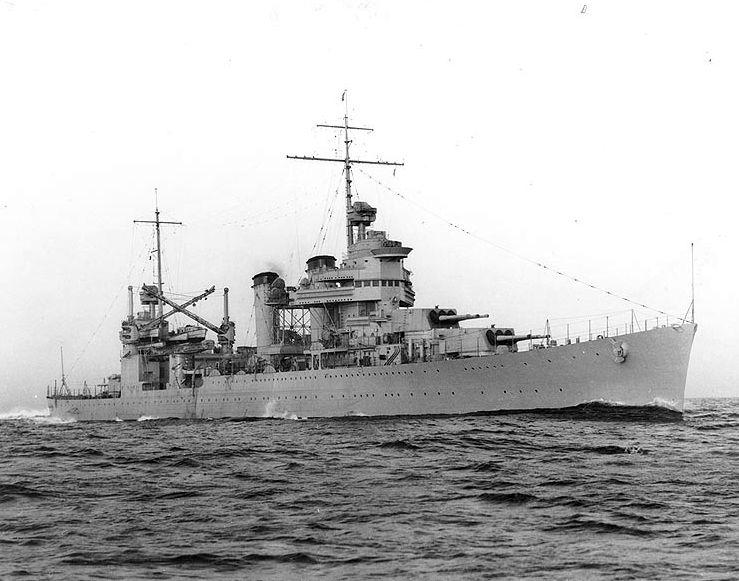

USS Vincennes was a New Orleans-class heavy cruiser and had entered service in 1937. Source: Navsource

Although Mikawa's squadron was spotted by Allied aircraft and a submarine, no action was undertaken on any of the reports. The destroyer USS Blue, equipped with radar, also did not observe the Japanese ships approaching. Also, the Allied warships had entered alert phase II, which meant that half of the crew was given rest after having endured trying days in the highest state of war readiness and under hot and humid conditions. Due to this peculiar mixture of circumstances, the Japanese attack took the Allies by total surprise. At 01:31 Mikawa gave the order: "Every ship attack!"

The Japanese ships each selected their own targets and independently attacked the Allied warships of the Southern Force. The Japanese cruisers had launched their float planes, and they were dropping flares over the USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra. Moments later, the Australian cruiser was hit by Japanese shells, which brought the ship to a standstill. Almost simultaneously the unfortunate vessel was hit by two torpedoes. The bow of USS Chicago was struck by a torpedo from the Kako and the heavy cruiser sailed away from the transports she was assigned to protect. The destroyers USS Patterson and USS Bagley both approached the Japanese ships and fired torpedoes and grenades. The Japanese took a few hits from shells, but none from torpedoes.

At 02:16 the Japanese ships aborted their attack and assembled north of Savo Island, out of range of the Allied ships. Mikawa quickly consulted with his staff and decided to return to Rabaul. The main reasons were that it would take some time to reload the torpedo tubes on board the cruisers, a looming shortage of ammunition and the risk of being attacked by Admiral Fletcher's Allied carrier fleet.

Meanwhile, the crew of USS Quincy and USS Vincennes tried in vain to put out the fires on board of their badly damaged ships. At 02:38, the Quincy disappeared into the waves of Ironbottom Sound and twelve minutes later the Vincennes followed. At 04:00, USS Patterson came alongside HMAS Canberra to assist in controlling its damage, but Rear Admiral Turner ordered the heavy Australian cruiser to be scuttled if the ship could not follow his retreating fleet on her own. The destroyers USS Selfridge and USS Ellet took the survivors of the Australian cruiser on board and sank the heavily damaged ship with 300 shells and five torpedoes. The Astoria was also damaged beyond repair and sank around noon on August 9, 1942. USS Chicago had suffered a damaged bow and was able to divert to Nouméa for emergency repairs and arrived in San Francisco on October 13, 1942, for permanent repairs.

Despite the resounding victory, the Japanese still suffered losses in the aftermath of the Battle of Savo Island. Before the Japanese heavy cruiser Kako could reach her home base in Kavieng, the ship was sunk by the American submarine USS S-44. Mikawa's other ships escaped with minor damage. Rear Admiral Mikawa initially received congratulations from his superiors, but later faced a lot of criticism. His decision to spare his ships and therefore fail to destroy Rear Admiral Turner's unarmed transports, proved to be decisive in the negative outcome for the Japanese forces after the Battle of Guadalcanal.

The Battle of Savo Island also marked the end of the Australian contribution to the battle for the southern Solomon Islands. The Australian Navy had already suffered major losses and the army troops from Down Under were deployed in North Africa and New Guinea, where the battle overland to Rabaul via the infamous Kokoda Trail was continued by the Australian ground forces.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Battle of the Tenaru River

The 11,000 Marines on Guadalcanal were left to fend for themselves with only half of the planned supplies because of the lost Battle of Savo Island by the US Navy. This allowed them to do no more than erect defensive barricades around the unfinished airport and at Lunga Point. After four days of hard work, all available supplies of their own and supplies left behind by the Japanese were brought within the defensive circle and the airstrip was completed. On August 12, 1942, the airport was named Henderson Field after Lofton R. Henderson, a Navy pilot who was killed during the Battle of Midway. Six days later the airport was already operational, but food supplies had to be rationed. In addition, many Marines suffered from dysentery from drinking polluted water.

On August 20, the escort aircraft carrier USS Long Island (CVE-1) delivered nineteen Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter aircraft and twelve Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers to Henderson Field. From August 22, these aircraft together with five Bell P-400 Airacobras from the army, formed the so-called Cactus Air Force (CAF), the flying group of the new airport on Guadalcanal. In fact, Henderson Field was an unsinkable aircraft carrier for the entire remainder of the Battle of Guadalcanal.

The Japanese army leadership wanted to recapture Guadalcanal and the strategically important Henderson Field as quickly as possible. However, for this purpose the Japanese only had three army units at their disposal. The 35th Infantry Brigade under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, which was stationed in Palau, the 4th Infantry Regiment which was stationed in the Philippines and the 28th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki which was on board transports near Guam. The three units were sent to Guadalcanal via Rabaul, but part of the Ichiki Regiment landed first on the American-occupied island at Taivu Point, east of Lunga Point and Henderson Field, on August 18.

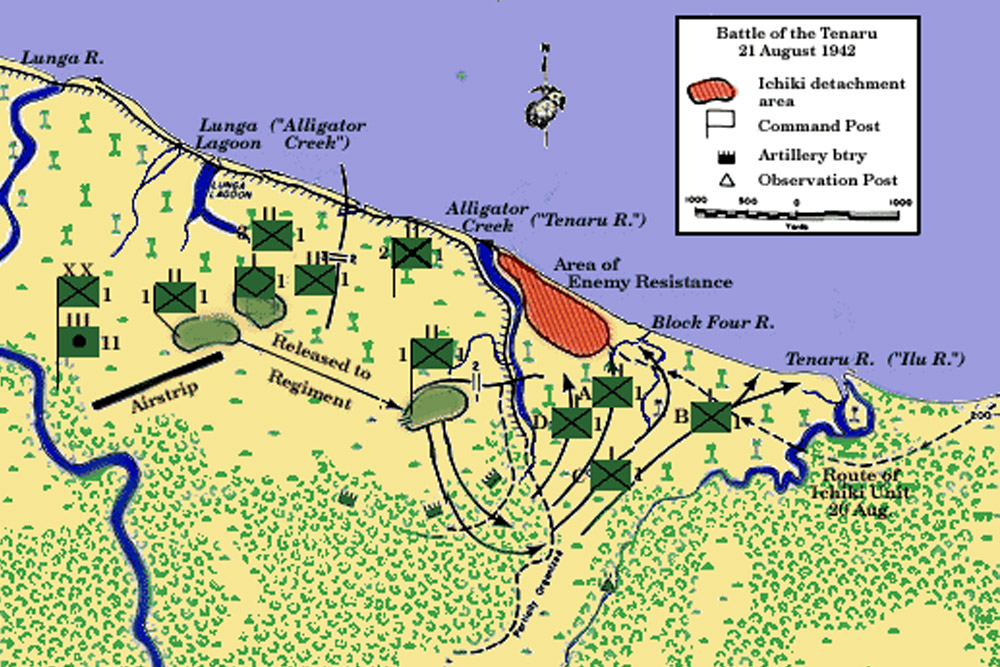

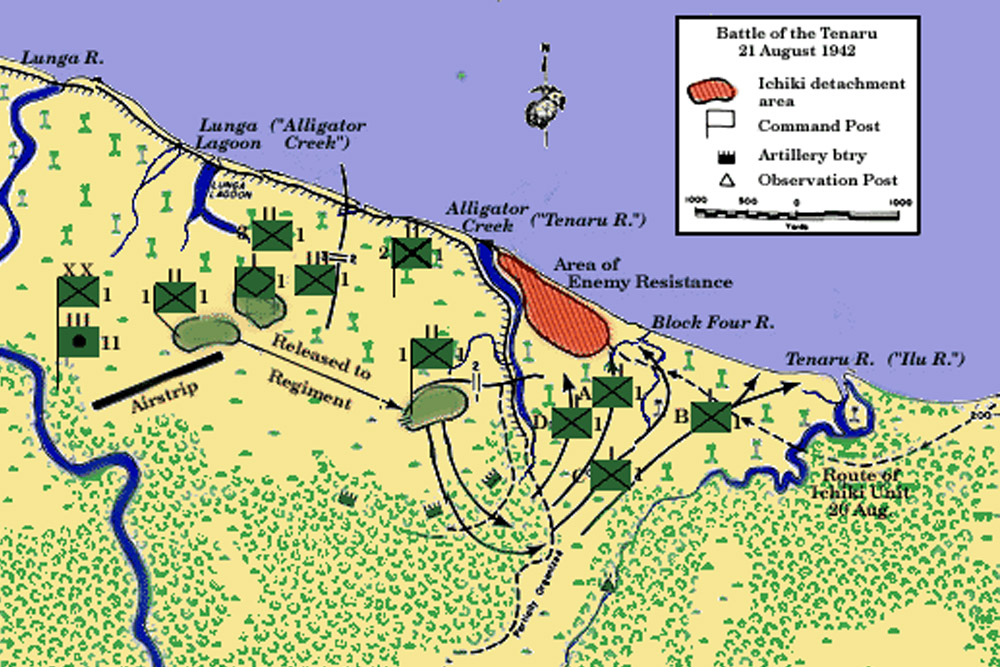

Colonel Ichiki completely underestimated the strength and fighting spirit of the Americans and decided not to wait for reinforcements. He marched fourteen miles through the jungle with his 917 men toward Henderson Field but encountered Marine defensive reinforcements near the Tenaru River in the early morning hours of August 21. Ichiki trusted his own expertise and the superiority of his men over the, in his view, cowardly Americans and ordered his infantrymen to attack. The first wave of Japanese attacks broke down on a wall of American machinegun fire. Ichiki responded with a mortar bombardment, after which he immediately ordered a new assault. This too failed due to a strong American defence. The carnage continued until the sun rose, making it even easier for the Marines to hit the enemy. The Americans counterattacked the remaining Japanese forces, ultimately killing 789 of the 917 Japanese soldiers. The remaining Japanese troops withdrew to Taivu Point and awaited orders after notifying their superiors. Colonel Ichiki committed ritual suicide after burning his regimental flag. Afterwards, the Marines were amazed by the Japanese's primitive tactics and willingness to sacrifice. General Vandegrift wrote: "I have never seen soldiers fighting like this. These people refuse to surrender. The wounded wait until our men come up to help them and blow themselves and the soldiers around them to pieces with a hand grenade.”

Definitielijst

- aircraft carrier

- A warship of large dimensions with the facilities for starting, landing and maintenance of aircrafts.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Midway

- Island in the Pacific where from 4 to 6 June 1942 a battle was fought between Japan and the United States. The battle of Midway was a turning point in the war in the Pacific resulting in a heavy defeat for the Japanese.

- mortar

- Canon that is able to fire its grenades, in a very curved trajectory at short range.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands

Colonel Ichiki would have been better off waiting for reinforcements, as they were already on their way. On August 16, three transport ships had already left Truk, one of the occupied Caroline Islands, carrying 1,411 troops of his 28th Infantry Regiment and 500 Marines of the 5th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force. The three slow transports were escorted by the light cruiser Jintsu, eight destroyers and four patrol boats under the command of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka. The convoy protection was further expanded with Rear Admiral Mikawa's four heavy cruisers sailing from Rabaul. These were the four surviving cruisers from the Battle of Savo Island.

Important reinforcements also appeared for the CAF. On August 22, five Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighter aircraft arrived. More than a week later, another nineteen Wildcats and twelve SDB Dauntless dive bombers from the USS Enterprise landed on Guadalcanal. At the end of August, Henderson Field had 64 fighter aircraft and 86 pilots.

Meanwhile, Commander-in-chief Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had assembled a strong fleet that also sailed from Truk on August 23. This fleet consisted of three divisions. Most importantly, the carrier division consisting of the aircraft carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku, the light aircraft carrier Ryujo (together 177 fighter aircraft), protected by a heavy cruiser and eight destroyers under Midway veteran Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. Furthermore, the vanguard force consisting of two battleships, four cruisers and three destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe and a forward fleet of four cruisers, six destroyers and the seaplane mothership Chitose under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo. This attack fleet would receive air cover from about a hundred fighter planes stationed in Rabaul.

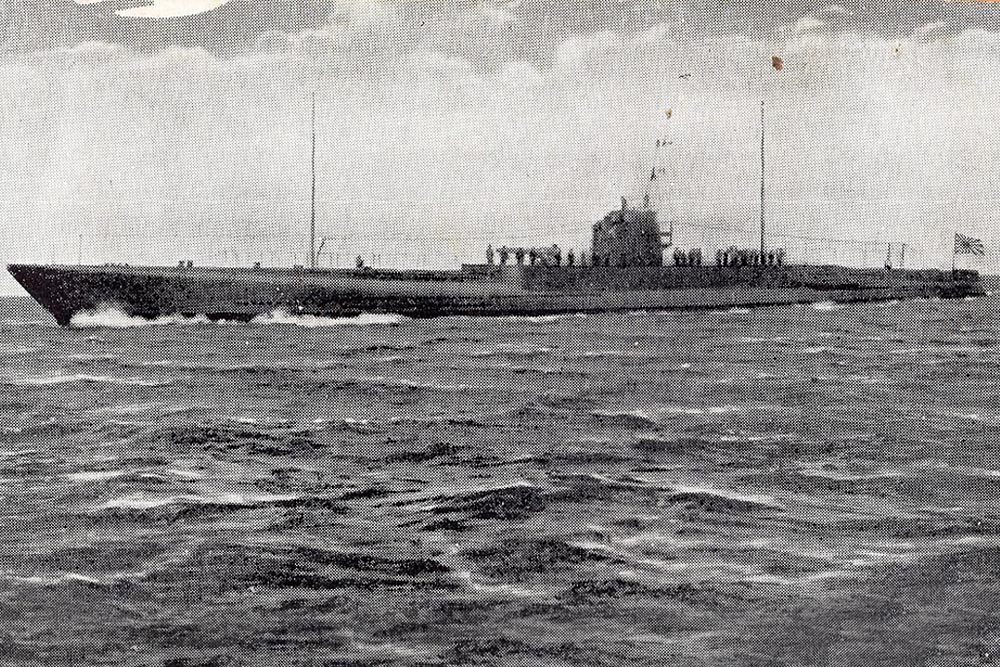

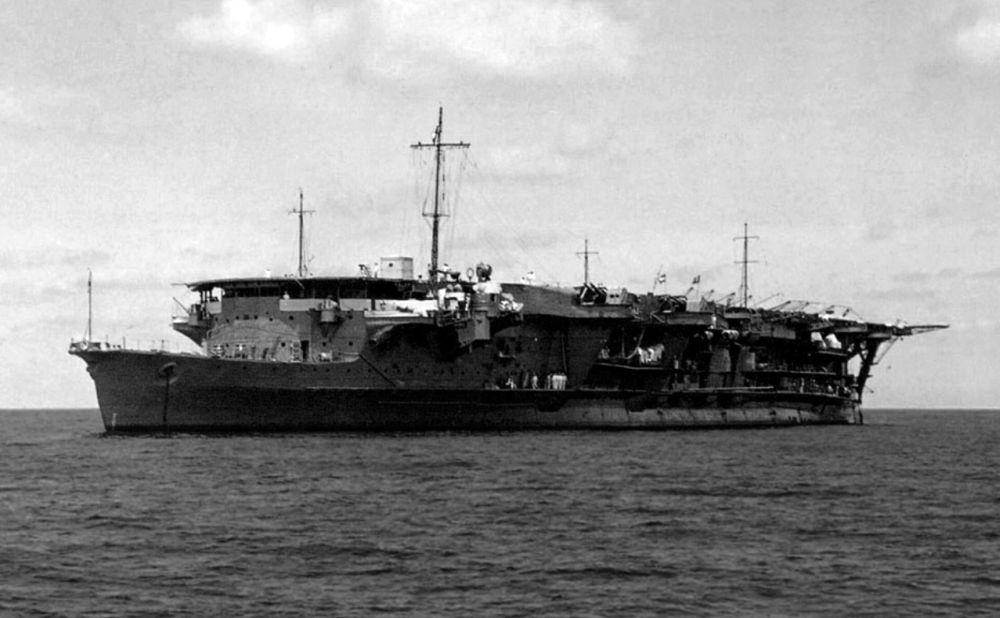

The light aircraft carrier Ryujo was built in 1929/1931 at the Mitsubishi shipyard in Yokohama. Source: World War 2 Database

Nimitz was unaware of the Imperial Japanese Navy's fleet movements but ordered Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher's aircraft carriers back towards the Solomon Islands to protect the Marines on Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Fletcher had the fleet carriers USS Enterprise and USS Saratoga and the light aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-7), which were escorted by the battleship USS Washington, four cruisers and eleven destroyers. The American aircraft carriers jointly had 176 fighter aircraft on board but could also count on the CAF aircraft stationed at Henderson Field.

Both the Japanese and the Americans despatched reconnaissance aircraft and on August 24 the fleets discovered each other. The Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands had started. Aircraft from USS Saratoga hit the Ryujo, which was serving as a decoy in a forward position, with several 1,000-pound bombs and an aerial torpedo. The light aircraft carrier was abandoned and sank during the night of 24 to 25 August. Japanese fighter planes of the Shokaku and Zuikaku aircraft carriers inflicted heavy damage on USS Enterprise. After these mutual air attacks, both fleets withdrew. The battle ended in favour of the Americans, although the Enterprise required repairs that would take months. The Japanese not only lost the Ryujo, but also 75 aircraft as opposed to the enemy who lost only twenty.

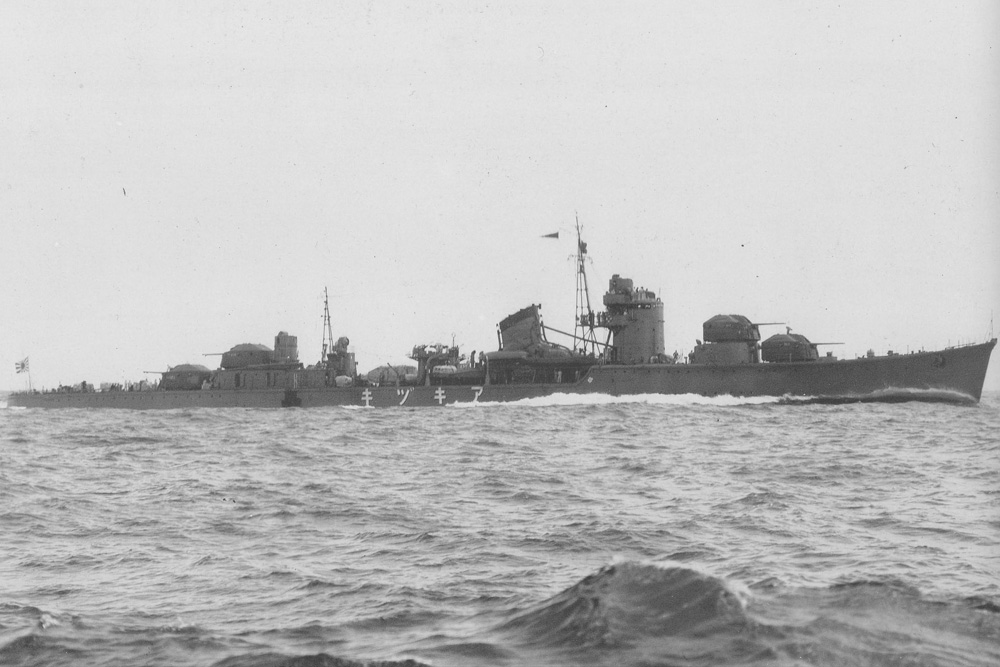

On August 25, Tanaka's convoy was attacked by CAF aircraft from Henderson Field. The Americans succeeded in sinking one of the transports and the destroyer Mutsuki and inflicting heavy damage on the light cruiser Jintsu and the Chitose. Tanaka then decided to withdraw his convoy to the Shortland Islands, the northernmost of the Solomon Islands, where the surviving troops were taken aboard the destroyers that would make another attempt to land the soldiers on Guadalcanal on August 28.

At this stage of the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Japanese had an advantage over the Americans. Among other things, they had more ships and aircraft. However, after the Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands, they withdrew because they believed they had damaged two American aircraft carriers and destroyed one. The latter was supposed to have been the USS Hornet (CV-8), but this carrier had not even participated in the battle. Because USS Enterprise had despatched some of its aircraft to Guadalcanal, the Cactus Air Force had become an air force to be reckoned with. Tanaka's destroyers found out to their cost when they were attacked by the CAF during the night of 28 to 29 August. The Asagiri was sunk and the Jugiri and the Sjirakuma suffered extensive damage during the troop transport towards Guadalcanal.

On September 3, US Marine Corps Brigadier General Roy S. Geiger, commander of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, arrived on Guadalcanal with his staff. He took command of the CAF and thus took some of the weight off General Vandegrift’s shoulders. From the end of August, Japanese aircraft from Rabaul undertook air raids on Henderson Field almost every day. There were aircraft losses on both sides, but the American aircrews were almost always rescued. The Japanese pilots and crew members, on the other hand, were almost always killed. Gradually but surely, the Japanese lost so many experienced pilots, who could no longer be replaced, causing the air raids to have a diminishing effect.

After the Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands, the Americans received reinforcements from the US Marine Corps. Source: Britannica

These reinforcements included LVTs (Landing Vehicle Tracked), nicknamed Alligators and Water Buffalos. Source: World War Photos

Meanwhile, General Vandegrift had expanded his garrison on Guadalcanal by 1,500 troops at the expense of the occupying forces on Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo. This included commandos from the 1st Marine Raider Battalion, commanded by Colonel Merrit A. Edson. In addition, small Allied convoys managed to reach Lunga Point and supply the Marines within the defensive belt. On September 1, one of these convoys landed 392 so-called Seabees. These were members of the US Naval Construction Battalions, tasked with maintaining and improving Henderson Field so that the Marines could focus on defending the airstrip.

Supervised by the Seabees, Henderson Field was reinforced with Marsden Mats, among others. Source: World War Photos

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Midway

- Island in the Pacific where from 4 to 6 June 1942 a battle was fought between Japan and the United States. The battle of Midway was a turning point in the war in the Pacific resulting in a heavy defeat for the Japanese.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Tokyo Express

The damage suffered by Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka's troop convoy during the Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands had made the Japanese naval leadership decide to transport ground troops for Guadalcanal by destroyers only. The two remaining troopships were sent back to Rabaul and some naval bases for destroyers were hastily constructed on the Shortland Islands. Between August 29 and September 4, Japanese destroyers managed to land 5,000 troops at Taivu Point, mostly from the 35th Infantry Brigade under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi. From the Shortlands, Tanaka's destroyers were able to traverse The Slot (the nickname for the New Georgia Sound, the waterway that runs through the middle of the Salomon Islands archipelago) in a single night and drop troops and pound targets on Guadalcanal. At one point this supply of troops and coastal bombardments became so regular that the Americans called it the Tokyo Express.

The biggest disadvantage for the Japanese was that this method of transport prevented them from landing heavy weapons. Furthermore, the Tokyo Express monopolised the available Japanese destroyers so that other convoys could not be sufficiently protected, particularly against submarine attacks. By contrast, the crews of the American naval vessels were still not adequately trained for night operations. So, the Japanese continued to rule the seas around the Solomon Islands at night. During the day, the CAF largely controlled the sky and therefore determined what happened on the surface of these waters. This situation would remain like this for months to come.

General Kawaguchi, who had landed at Taivu Point on August 31, took command of all Japanese forces on Guadalcanal. Like the Americans at Henderson Field, Kawaguchi's Japanese soldiers were bombed almost daily and both sides suffered from a chronic lack of fresh food and clean water. The hot and humid climate made life miserable for both sides and diseases and tropical vermin flourished in equal measure.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

Battle of Edson's Ridge

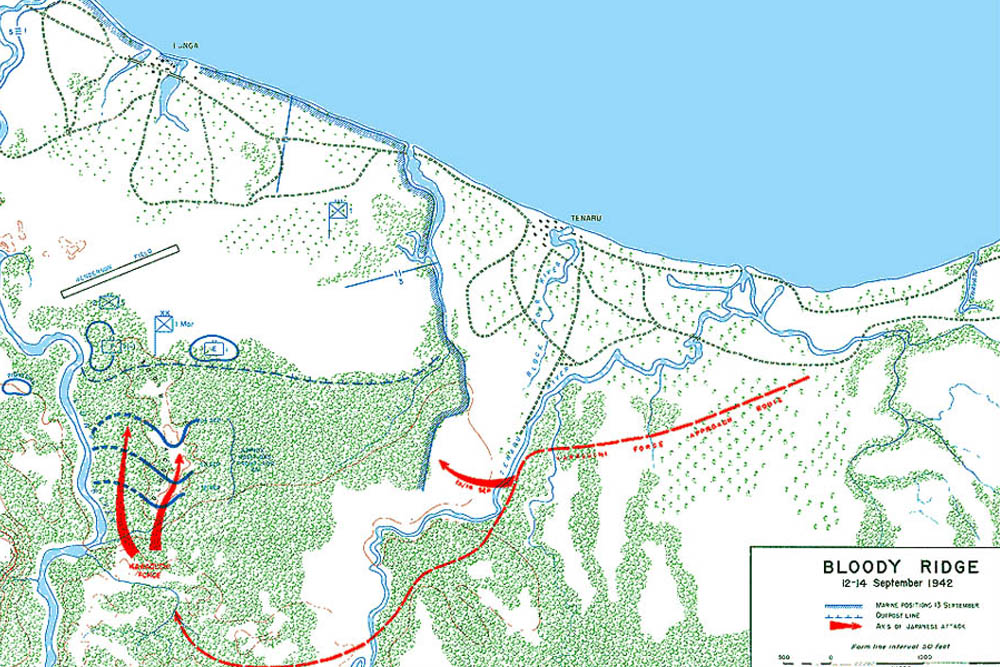

On September 7, General Kawaguchi divided his men into three attack groups. 1,000 troops under Colonel Akinosuke Oka would attack the American defence belt, the perimeter, from the west while the 1,000 troops of the Kuma Battalion would approach from the east. Kawaguchi himself would lead more than 3,000 troops who would then invade the perimeter in its centre. 250 Japanese soldiers remained behind to defend the supply base at Taivu Point.

Meanwhile, native scouts led by Martin Clemens, a coast guardsman of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force, had reported Japanese troop movements to the American defenders of Henderson Field. Colonel Edson decided to launch a commando attack on the remaining Japanese at Taivu Point. On September 8, his 500 Marine commandos landed by boat at the village of Tasimboko near Taivu Point. The Japanese fled into the jungle and the Americans destroyed Japanese supplies and captured their confidential documents. As a result, Colonel Austin Edson became aware that the main Japanese force would attack the perimeter through a narrow, 3,000-foot-long cliff that ran parallel to the Lunga River, nearly six miles south of Henderson Field. The cliff, called Lunga Ridge, was still virtually undefended, but Colonel Edson stationed his entire battalion of 840 Marine commandos on and around the escarpment.

During the night of September 12-13, Kawaguchi's first battalion attacked the leading defenders of Lunga Ridge, forcing them to withdraw. The next night, the 3,000 men of Kawaguchi's main force attacked the US Marines' hill position. The Japanese attack was initially repulsed by the Americans, although the latter had to withdraw again. The battle resulted into direct Japanese attacks on the Marines' positions and even into hand-to-hand combat. The Japanese suffered great losses but continued their attacks. A flanking attack by Japanese troops also failed to subdue the American defence. By morning, CAF air strikes put a definitive end to the Japanese assault. On September 14, Kawaguchi led his remaining troops on a five-day march into the Matanikau Valley, west of Lunga Point near Cape Cruz, where he encountered the remnants of Oka's battalion. During the Battle of Lunga Ridge, 850 Japanese soldiers and 59 American Marines had died. The cliff was then named Edson's Ridge but was called Bloody Ridge by the Americans.

After the Japanese naval and army leaders received the news of Kawaguchi's defeat, they concluded that the Battle of Guadalcanal could be decisive for the course of the war in the Pacific. They therefore decided that the recapture of Guadalcanal should take priority over the conquest of New Guinea. The attack on the capital of New Guinea, Port Moresby, (the operating base for the Kokoda trail and the air base of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), was therefore aborted to free up resources for the capture of Henderson Field.

General Vandegrift ordered another Marine regiment from Tulagi to strengthen the defences of Edson's Ridge. On September 18, an Allied convoy put ashore 4,157 troops from the 7th and 11th Marine Regiments, including auxiliary troops, at Lunga Point. The convoy also delivered 137 vehicles, aviation fuel, ammunition, food supplies and spare parts. These reinforcements allowed Vandegrift to establish a continuous line of defence around the Lunga perimeter. However, the supply of American reinforcements had come at a high price. The light aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-7) had been torpedoed and sunk by the Japanese submarine I-19 while protecting the convoy on 15 September.

Between September 14 and 27, the airspace above the Solomon Islands remained quiet due to bad weather. Both sides took advantage of the breathing space to expand their air fleets. On September 20, Brigadier General Geiger had 71 fighters available at Henderson Field. This provided him the upper hand when the Battle of Guadalcanal resumed on September 27 due to a Japanese air attack on the airstrip and the CAF was able to repel it before any major damage could be inflicted.

In this phase of the battle the Japanese began to prepare their next attack on the heavily contested airfield. The 3rd Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment had already landed on Guadalcanal on September 11, but too late to participate in Kawaguchi's failed attack. The battalion then joined the remnants of Oka's troops near the Matanikau River. The Tokyo Express dropped off supplies and ammunition and 280 troops at Kamimbo on September 14, 20, 21 and 24. From September 13 onwards, the 2nd and 38th Infantry Divisions were transported from the Dutch East Indies to Rabaul. 17,500 men from these divisions should constitute the vanguard for the next assault on the Lunga perimeter.

During the Battle of Lunga Ridge, mortars were both an important defensive and offensive weapon. Source: World War Photos

This captured Japanese Type 92 Howitzer also served the American Marines well. Source: World War Photos

Definitielijst

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

Battle of Cape Esperance

The area between Lunga Point and the Matanikau River was infested with small groups of Japanese soldiers and General Vandegrift had his Marines launch several attacks to prevent these groups from joining together. A more intense battle followed between October 6 and 9, when the Americans crossed the Matanikau and attacked newly arrived Japanese troops. They inflicted significant losses on the 2nd Infantry Division and the 4th Infantry Regiment.

Next to continuously attacking the Japanese, the Americans responded to the Japanese troop buildup by sending in their own reinforcements. On October 8, the 2,837 troops of the 164th Infantry Regiment of the US Army's Americal Division embarked on New Caledonia. Task Force 64, which consisted of the heavy cruisers USS San Francisco and USS Salt Lake City, the light cruisers USS Boise (CL-47) and USS Helena (CL-50), and five destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Norman Scott, was ordered to cover the landing of the army troops. Meanwhile, the Japanese planned a Tokyo Express run on the night of October 11 to 12. Two seaplane tenders and six destroyers had to unload 728 soldiers with artillery and ammunition on Guadalcanal. At the same time, three heavy cruisers and two destroyers, led by Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto, would bombard Henderson Field. Because the US Navy had not yet made any attempt to stop the Tokyo Express, Goto and Tanaka did not expect any intervention from American ships.

Just before midnight, Scott's ships spotted Goto's force on their radar screens near the passage between Savo Island and Guadalcanal, off Cape Esperance. The Americans attacked their opponents in a so-called ‘crossing the T’ tactic in which a line of warships crosses in front of a line of enemy ships (the two lines then forming a ‘T’). This enables the crossing line to bring all their guns (both forward and aft) to bear while it can only receive fire from the forward guns of the enemy.” The US Navy ships soon exploited this tactical advantage and almost immediately struck the heavy cruisers Aoba and Furutaka and the destroyer Fubuki.

Furutaka and Fubuki sank while the Aoba was severely damaged. Rear Admiral Goto was severely wounded and aborted his attempt to bomb Henderson Field. The ships of the Tokyo Express were able to complete their mission in relative peace, but four of the destroyers returned early on the morning of October 12 to assist Goto's battered task force. Later that day, the Natsugumo and the Murakumo were sunk by CAF aircraft. The next day, the American army convoy was able to safely reach Guadalcanal and put all men and supplies ashore.

After the Battle of Cape Esperance was won, American reinforcements were able to land relatively easily. Source: World War Photos

Definitielijst

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

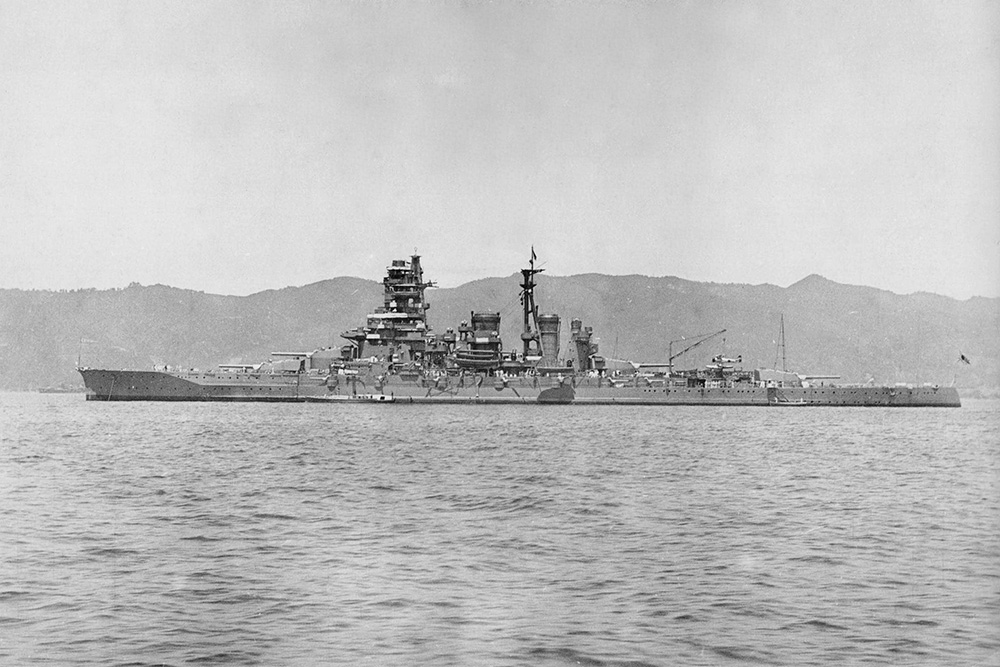

Battle of Henderson Field

The American victory at Cape Esperance did not deter the Japanese from pursuing their invasion plans of Guadalcanal. They even decided on an all-or-nothing effort by landing 4,500 troops at once using six transports. On October 13, the transports, protected by eight destroyers, left the Shortlands. On board were men from the 16th and 230th Infantry Regiments, Marines, two batteries of heavy artillery and a tank company. To prevent the CAF from stopping the convoy, Yamamoto despatched the two battleships Kongo and Haruna (1915) to Guadalcanal and had Henderson Field bombarded with more than 970 14-inch shells on the night of October 14 to 15. Fired from 10 miles nearly all of the shells hit Henderson Field destroying the two airstrips, 48 fighter planes, virtually all of the aviation fuel, and killing 41 men, including six CAF pilots.

Immediately after the bombardment, the Japanese battleships withdrew and, together with their accompanying cruiser and eight destroyers, sailed back to Truk. Despite the extensive damage, the Seabees at Henderson Field were able to temporarily repair one of the two runways within a few hours. The remaining 42 aircraft were refuelled with gasoline siphoned off the damaged aircraft and from hidden supplies that were quickly recovered from tanks buried in the ground. Transport planes with aviation fuel were sent from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal, but before they arrived the CAF aircraft had already gone airborne to launch an attack on the Japanese convoy which had landed at Tassafaronga, ten miles west of Lunga Point, on midnight October 14. The Japanese had had almost two days to put their men and materials ashore, so the Americans sank two transport ships that were already empty and damaged two others.

The Japanese had succeeded in their objectives. Army General Harukichi Hyakutake, who had been put in charge of all Japanese forces on Guadalcanal, now had 20,000 troops, tanks, heavy and light artillery, and sufficient ammunition and food supplies at his disposal. Because the Americans were driving their enemies from their positions on the Matanikau River and attacking along the coast was considered too dangerous, Hyakutake decided to attack Henderson Field from the south, out of the jungle, just as Kawaguchi had done previously. 7,000 soldiers would move through the jungle and attack from the eastern bank of the Lunga River. To distract the American troops defending the airbase, 2,900 Japanese infantrymen, supported by tanks, would attack from the coastal strip to the west of the airport. The Japanese estimated the American strength at about 10,000 men, but in fact there were about 23,000.

As of October 12, Japanese engineers had already begun to clear a strip of jungle from the Matanikau River to the south of the Lunga perimeter. The fifteen-mile stretch crossed rivers, went through muddy ravines and swamps, over cliffs and across dense jungle. The strip was called the Maruyama Road, named after the commander of the 7,000 men who would follow the trail, General Masao Maruyama. The attack was planned for October 23.

However, on October 23, Maruyama's men were still struggling on the trail through the jungle. Hyakutake was unaware of this and allowed the distractive attack at the mouth of the Matanikau River on the defensive positions to the west of the air base, to proceed on the 23rd. However, the ten tanks and many of the Japanese soldiers were quickly neutralized by American artillery, mainly 75mm pack howitzers. By the end of the day on October 24, Maruyama's forces had finally reached the southern fringe of the Lunga perimeter. Maruyama had his exhausted men attack the American defensive positions almost immediately, but they were caught in a barrage of machine gun bullets, mortar shells and 37mm anti-tank grenades. Some small groups of Japanese were able to break through the defensive lines but were hunted down over the next few days and all the soldiers were killed. After several direct attacks, Maruyama had to withdraw his troops into the jungle. About 1,500 of his men had been killed.

Meanwhile, the remaining CAF fighters were busy repelling Japanese air attacks and naval bombardments. During these battles, the Americans shot down fourteen enemy aircraft and sank the light cruiser Yura. The CAF's successes were largely due to the fact that the Japanese naval leadership assumed that the ground forces would succeed in capturing Henderson Field.

Further Japanese attacks at the Matanikau River were also repulsed by the Americans, with many Japanese killed. On October 26, General Hyakutake halted all assaults and ordered his men to withdraw. It was not until November 4 that the first Japanese survivors reached the base camps west of the Matanikau River and Koli Point, east of the American line of defence. The battalions were severely depleted by hunger and tropical diseases. All the wounded had been left behind. In total, the Japanese lost between 2,200 and 3,000 men, while the Americans only suffered eighty deaths. The remaining Japanese could no longer take the offensive due to lack of material and were forced to fight defensively during the remainder of the Battle of Guadalcanal. This Japanese attempt to retake Henderson Field had also failed miserably.

SBD Dauntless dive bombers at Henderson Field. Because the airfield remained intact throughout the Battle of Guadalcanal, the CAF was able to continue to inflict decisive losses on the Japanese. Source: Britannica

Yet Henderson Field regularly suffered heavy damage, such as shown here during the battle for the air strip. Source: Public domain

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- mortar

- Canon that is able to fire its grenades, in a very curved trajectory at short range.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

While General Hyakutake's Japanese forces were conducting their overland attacks on the Lunga perimeter, the Japanese fleet aircraft carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku and the light carriers Zuiho and Junyo arrived in The Slot with four battleships, eight heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and 25 destroyers, commanded by Admirals Nagumo, Kondo and Abe. Yamamoto hoped that the ground forces' attack on Guadalcanal would draw out the American aircraft carriers and thus enable him to deal with them once and for all.

Meanwhile, on October 25, American Task Groups with the aircraft carriers USS Hornet (CV-8) and USS Enterprise (CV-6) searched for Japanese surface ships north of the Santa Cruz Islands, New Hebrides. By October 26, the two fleets had come within about 200 nautical miles of each other, and both were aware of each other's presence. Dozens of fighter planes were launched from the six flight decks, but the Japanese aircraft were the first to spot the Task Force around USS Hornet. The Japanese launched a massive attack on the American aircraft carrier and the Hornet was hit by three bombs and two torpedoes. In addition, two Aichi D3A dive bombers deliberately crashed into the US aircraft carrier after being hit by anti-aircraft fire. The carrier came to a standstill and the heavy cruiser USS Northampton towed the badly damaged aircraft carrier away from the battle. The Hornet's crew managed to restore power to some of the Babcock & Wilcox boilers just as the aircraft carrier was attacked by nine Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers. Eight of these Japanese aircraft were shot down or failed to score any hits, but the ninth aircraft placed a torpedo hit on the Hornet's starboard side. The hit dashed all efforts to repair the damage to the boilers and caused the aircraft carrier to list fourteen degrees.

Japanese dive bombers attack USS Hornet during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, October 26, 1942. Source: Public domain

Halsey ordered the USS Hornet, considered lost, to be sunk so that the wrecked ship could not fall into Japanese hands. The destroyers that had escorted the aircraft carrier took the Hornet's crew on board and launched a total of nine torpedoes and fired more than 400 12.5cm shells at the abandoned ship but failed to sink it. The American destroyers had to divert as the Japanese surface fleet approached. The Japanese destroyers Makigumo and Akigumo finally sank the aircraft carrier with four torpedoes. USS Hornet sank at 01:35 on October 27, 1942. The aircraft carrier had been in service for only a year and six days.

Hornet aircraft had meanwhile hit the Zuiho with four 500-pound bombs. The flight deck of the light Japanese carrier could no longer be used and the Zuiho played no further role in the naval battle. The Shokaku was also hit by several American bombs and the flight deck of the Japanese fleet carrier was soon ablaze. On October 26, the USS Enterprise also suffered several bomb hits; however, her flight deck remained intact and the carrier was able to take on board the remaining aircraft from USS Hornet. The Americans had lost 81 planes and only a fraction of the pilots had been rescued.

In the end, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands remained inconclusive once the Japanese decided to withdraw their powerful fleet due to a fuel shortage. They may have achieved a tactical victory by sinking an enemy carrier and a destroyer and damaging some other ships, but their own loss of 99 aircraft fighters and their experienced pilots could not be replaced. Admiral Nagumo was relieved of his duties shortly after the battle and was posted ashore. He noted: "The Naval Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands was a tactical victory, but a crushing strategic loss for Japan...Given the tremendous superiority of our enemy's industrial capacity, we had to win every battle decisively. This last battle, though unfortunately perceived as a victory, it was not a conclusive one." Once again, the Imperial Japanese Navy had failed to deal with a weaker and exhausted enemy fleet.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

The Americans on the offensive

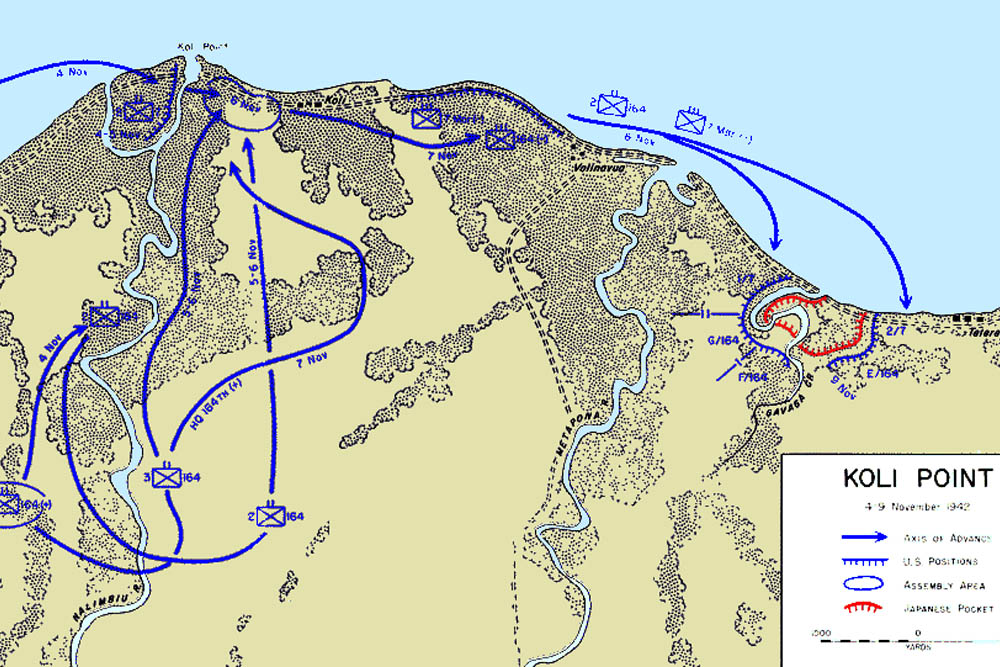

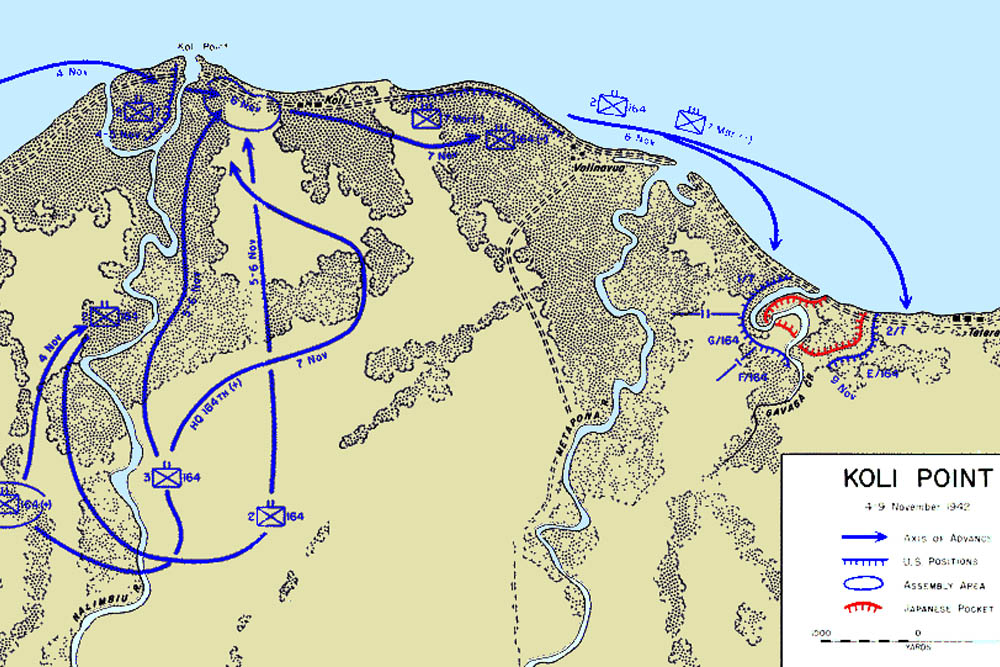

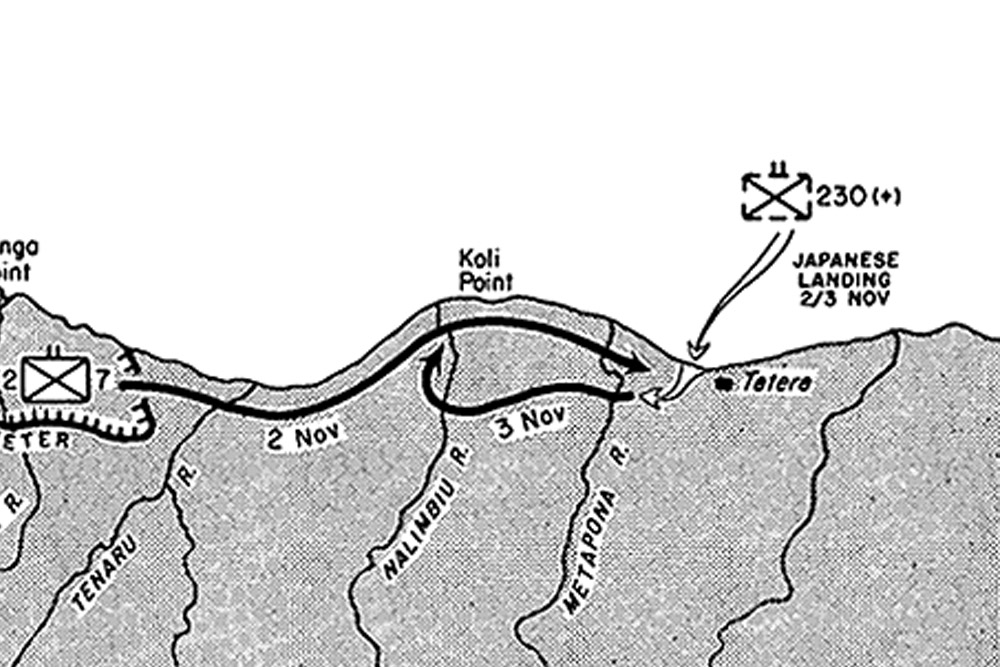

To take full advantage of the victory at the Battle of Henderson Field, General Vandegrift, on November 1, deployed six Marine and one Army battalion west of the Matanikau River to expel the Japanese forces. This offensive was commanded by Colonel Merrit Edson. The Japanese had already been defeated at Point Cruz on November 3. The Americans then shifted their attention to Koli Point where 300 fresh army troops had landed to assist their exhausted compatriots. After some fighting between November 9 and 11, 2,000 to 3,000 Japanese fled into the jungle. The remaining 450 soldiers were overrun by the Americans and almost all Japanese fought to the bitter end. In the following weeks, the Marines entered the jungle and hunted down the enemy. The Japanese were defeated in every battle or skirmish. Of the approximately 2,500 troops, only about 800 survived, who, after a harsh journey through the jungle, joined the remaining soldiers at the mouth of the Matanikau River and Mount Austen, a Japanese stronghold at a higher altitude. The Tokyo Express delivered small numbers of fresh troops on November 5, 7 and 9, but they could no longer make a difference. The frontline alongside the Matanikau River remained in a stalemate until the end of 1942.

Although the Japanese had lost the Battle of Henderson Field, they did not yet consider the war on Guadalcanal to be finished. They once again made plans to recapture the strategic airfield, for which more troops were required. Admiral Yamamoto arranged for eleven transport ships to transfer the remaining 7,000 troops of the 38th Infantry Division and their supplies from Rabaul to Guadalcanal. He further assigned the battleships Hiei (1914) and Kirishima (1915) to bombard Henderson Field with fragmentation grenades during the night of 12 to 13 November. Once the CAF had been eliminated, the landing of the Japanese ground forces should take place the next day. Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe was given command of the battleships and the accompanying light cruiser Nagara and eleven destroyers. Rear Admiral Tanaka commanded the transports and twelve accompanying destroyers.

After the Battle of Henderson Field, the Marines searched the jungle looking for Japanese snipers and remaining machine gun nests. Source: World War Photos

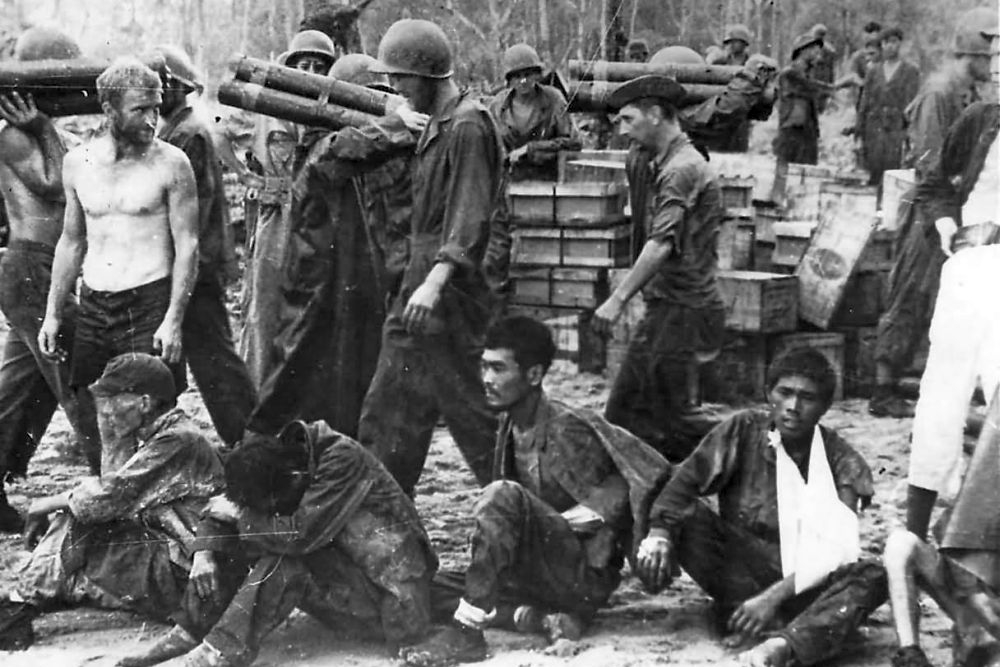

Japanese prisoners of war were not taken often; most Japanese soldiers fought to the end. Source: World War Photos

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Battle of Guadalcanal

American code breakers had already intercepted Japanese radio messages in early November and concluded the enemy was preparing for a new attempt. In response, the US Navy command despatched a supply convoy to Guadalcanal on November 11 under the command of Rear Admiral Turner. The convoy was protected by two task groups of warships, commanded by Rear Admirals Daniel J. Callaghan and Norman Scott respectively. Callaghan and Scott had at their disposal the heavy cruisers USS San Francisco and USS Portland, the three light cruisers USS Juneau, USS Helena (CL-50) and USS Atlanta (CL-51) and eight destroyers. On November 11 and 12, the American convoy was regularly attacked by Japanese fighter planes but was able to land men and supplies with relative ease. During these skirmishes the Japanese lost a further nine aircraft.

After this American success, there remained the objective of preventing the Japanese battleships from bombarding Henderson Field with the fragmentation grenades. The American ships were assembled under Rear Admiral Callaghan. On the night of November 12 to 13, 1942, Vice Admiral Abe's Japanese battle fleet approached Guadalcanal from the northwest, keeping Savo Island to starboard. Callaghan's ships approached from the east. The Japanese expected no significant resistance, and the inexperienced Callaghan misinterpreted his enemy's positions, which were beyond their original formations due to bad weather and an exceptionally dark night. What followed was a nighttime clash between unequal task groups, one of which was armed with fragmentation grenades instead of armour-piercing ammunition. However, the Japanese were adept at fighting at night and placed some American ships in brightly illuminated beams with their searchlights. Both Abe and Callaghan hesitated to open fire. The Japanese admiral because he had a task other than destroying enemy ships and the American admiral because he was overwhelmed.

The Japanese battleship Hiei was built in 1913 and modernised for the last time in 1939. Source: Public domain

01:48, the battleship Hiei (1914) and the destroyer Akatsuki opened fire on the brightly lit USS Atlanta. Several times shots were exchanged between ships that had visual or radar contact with each other. The Japanese fragmentation grenades were not very effective against the American ships, however, their long-range torpedoes proved ever so successful. USS Atlanta took the first hits and soon began to drift. The cruiser ended up in the line of fire of USS San Francisco and shells from the cruiser hit the bridge of the Atlanta. All crew members on the bridge of the American cruiser were killed, including Rear Admiral Scott.

USS Atlanta was the namesake of a class of eight light cruisers and was commissioned on December 24, 1941. Source: Public domain

In the meantime, the Hiei (1914) was hit from very close range by gun shells and machine gun fire from three American destroyers. Taskforce commander Abe suffered injuries. The San Francisco was hit in the steering engine room and could only maintain a circular course. Moments later, the bridge of the heavy cruiser was struck, killing both Rear Admiral Callaghan and Captain Cassin Young, commander of USS San Francisco. Outnumbered and without commanders, the American ships were destroyed one by one by their superior Japanese enemies. The destroyers USS Cushing, USS Laffey, USS Barton, USS Monssen and USS Aron Ward were sunk. Four of the five cruisers were severely damaged while several more destroyers suffered minor damage. In fact, only the light cruiser USS Helena and the destroyer USS Fletcher had emerged from the battle unscathed.

The Japanese lost the destroyers Akatsuki and Yudachi, while both battleships, the light cruiser Nagara and another eight destroyers were damaged. Despite the resounding victory, Abe decided to withdraw his fleet without bombarding Henderson Field. Tanaka's troop transport ships were also sent back. The reasons for this are still not entirely clear. Perhaps the Japanese commander’s decision was influenced by his own wounds and the deaths of some of his key staff officers, but he may also have been uncertain about the extent of loss on the American side. Furthermore, his ships were hopelessly scattered, and it might take until the next morning to regroup during which they could be attacked by the CAF still present.

To make matters worse for the Japanese, the damaged battleship Hiei was sunk by American fighter planes on the evening of November 13. Although USS Atlanta disappeared under the dark water surface of the Iron Bottom Sound that same evening because of the damage it had suffered and USS Juneau was sunk by the Japanese submarine I-26, the Battle of Guadalcanal became a strategic American victory. Because Abe had decided to withdraw his fleet at a time when the Americans were in dire straits, Gallaghan and Scott's sacrifice had bought the Americans enough time to leave Henderson Field and the CAF undamaged. Admiral Yamamoto removed Abe from his position and had him replaced by Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo. He was immediately ordered to bomb Henderson Field with his Second Fleet and the battleship Kirishima (1915) on the night of November 14 to 15.

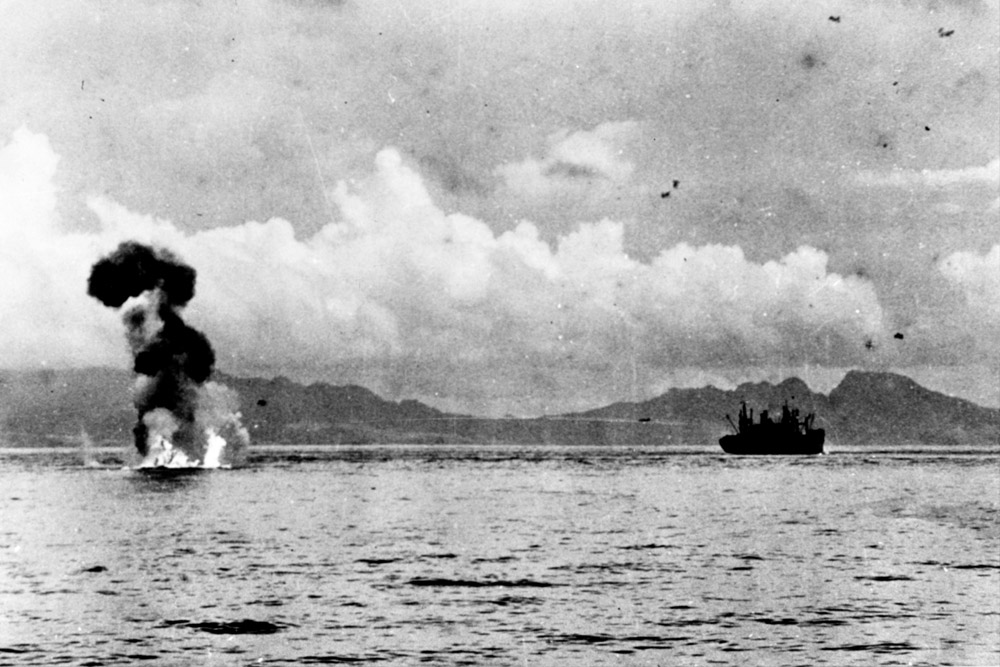

Before Rear Admiral Kondo's Second Fleet could come into action, Rear Admiral Mikawa attempted to bombard Henderson Field with the heavy cruisers Chokai, Kinugasa, Maya, and Suzuya, the light cruisers Isuzu and Tenryu, and six destroyers. Because the Americans were still in dire straits, Mikawa was able to reach Guadalcanal almost undisturbed and he had the heavily contested airfield bombarded for 35 minutes on the night of November 13 to 14. The airfield suffered heavy damage but continued to be operational. At first light, both Mikawa's cruisers and Tanaka's transports were attacked by American fighters from the CAF, the USS Enterprise and Espiriti Santo. The heavy cruiser Kinugasa was sunk and the Maya suffered heavy damage. Even worse for the Japanese, American pilots sank seven of Rear Admiral Tanaka's eleven troopships, killing hundreds of Japanese soldiers. The accompanying destroyers picked up as many survivors as possible but were themselves attacked by American aircraft.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Second Battle of Guadalcanal

Rear Admiral Tanaka received orders on November 14 to sail back to Guadalcanal with the remainder of his fleet of troop transports. The same night he was joined by Kondo and his attack fleet. This consisted of the battleship Kirishima (1915), the two heavy cruisers Atago and Takao, the two light cruisers Nagara and Sendai and nine destroyers. Admiral Halsey was forced to despatch several battleships from the protection group of the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise to Guadalcanal to defend it. These were the USS Washington and USS South Dakota, escorted by four destroyers. This small task group was commanded by Admiral Willis Augustus Lee. By midnight on November 14, the two enemy fleets were in the vicinity of Savo Island.

Rear Admiral Kondo instructed several groups of light cruisers and destroyers to patrol around Savo Island. These small groups were soon fired upon by the American battleships but escaped undamaged. They were then attacked by the four American destroyers, but the Japanese ships defeated these quickly and efficiently with gun shells and torpedoes. The USS Walke and USS Preston were immediately sunk, and the USS Benham and USS Gwin were severely damaged. Whereas the destroyers had completed their mission to absorb the initial impact of the Japanese attack, Admiral Kondo, however, was convinced that the American fleet had been defeated. He ordered the Kirishima, Atago and Takao to carry out the bombardment of Henderson Field.

Shortly after midnight the Japanese fleet gained visual contact with the USS South Dakota. The battleship was illuminated by the burning wreckage of the Benham and moments later was hit by 26 shells, mostly from the Kirishima. However, the American battleship also placed several hits on her Japanese opponent. Kondo, however, had not taken the USS Washington into account. The American battleship was able to approach the Japanese undetected up to 9,000 meters and opened fire on the Kirishima. The Japanese battleship was badly hit and put out of action. Before Kondo could give chase, the Washington disappeared towards Russell Island. At 01:04, Kondo ordered his ships to withdraw.

The Kirishima (1915) capsized and sank at 03:25 on November 15. Less than half an hour later, Rear Admiral Tanaka's remaining four transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal. At 05:55 they were attacked by CAF aircraft and came under fire by artillery from the American ground forces. In the ensuing chaos, the destroyer USS Meade approached the Japanese who were trying to land and fired on the transports. These joint attacks resulted in the four transports catching fire and destroying virtually all Japanese supplies, ammunition and heavy equipment. Only 2,000 to 3,000 Japanese troops of the 38th Infantry Division managed to land unscathed.

The Japanese battleship Kirishima was involved in both naval battles off Guadalcanal but was sunk during the second one. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock

After the Second Battle of Guadalcanal, the Imperial Japanese Navy depended on the Tokyo Express to deliver reinforcements and supplies to the hard-fought island. This forced the Japanese to abandon their November attempts to retake Henderson Field. Moreover, the Japanese army had to set priorities because the Allies started a major offensive in New Guinea. Because Rabaul, the most important Japanese naval base outside Japan, was much more directly threatened from New Guinea than from the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal received less and less attention.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Battle of Tassafaronga

From mid-November, Rear Admiral Tanaka had been ordered to supply the remaining troops on Guadalcanal. With his ships constantly under attack by the CAF, his staff had devised a plan. This plan consisted of delivering supplies through cleaned oil drums, which were half filled with ammunition, medicine, food and clean water. Tanaka's destroyers from the Tokyo Express would approach Guadalcanal at Tassafaronga at high speed, turn sharply and jettison the drums. The barrels connected with rope and equipped with buoys and floats, would then have to be picked up from land and brought in.

On November 30, 1942, Tanaka was ordered to make the first of five drum deliveries. However, the Americans had intercepted communications regarding the Japanese resupply attempt and Admiral Halsey despatched the newly formed Task Force 67. This TF consisted of the heavy cruisers USS Minneapolis, USS New Orleans, USS Pensacola and USS Northampton, the light cruiser USS Honolulu (CL-48) and six destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright.

USS Northampton was the namesake of a class of six heavy cruisers and was commissioned on May 17, 1930. Source: Public domain

At 10:40, Tanaka approached the coast of Guadalcanal with his eight destroyers. Wright's destroyers soon spotted the Japanese on their radar screens and opened a massive torpedo attack. Miraculously, all American underwater projectiles missed their target while the cruisers opened fire on the Japanese ships with their guns. Tanaka's ships aborted their resupply attempt and fired 44 long-range torpedoes at the American cruisers. The four heavy cruisers suffered heavy damage after being hit by several Japanese torpedoes. The Japanese destroyer Takanami was the only Japanese ship damaged by American cruiser fire. The destroyer was abandoned burning fiercely and sank after a heavy explosion at 01:30 on 1 December. The USS Northampton was abandoned at the same time after the crew reported being unable to control the fires and further listing of the ship. The cruiser sank an hour and a half later.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Japanese surrender and evacuation

After the failed resupply action of Rear Admiral Tanaka on November 30, the Japanese were unable to make another attempt to supply food and medicine to the exhausted troops on Guadalcanal. In early December, the Japanese garrison on the island was losing about fifty men every day to malnutrition and disease. On December 12, the Imperial Japanese Navy proposed to the Japanese military leadership that Guadalcanal be abandoned.

By December 1942, the American infrastructure had been significantly improved using the resourceful Seabees. In this photo a bridge supported by amphibious tractors. Source: World War Photos

A lot of Japanese equipment was also captured, such as this 75mm cannon that was used in the defence of the Lunga Perimeter. Source: World War Photos

On December 9, 1942, US Army Major General Alexander Patch took over command of the American occupation forces from General Vandegrift. By this time, the 1st Marine Division had also been relieved by the 2nd Marine Division, the US Army's 25th Infantry Division and the 23rd Americal Division. By January 1943, the American force numbered more than 50,000 men. The first order General Patch gave to his army troops was the attack on Japanese positions on Mount Austen, which would take weeks to complete.

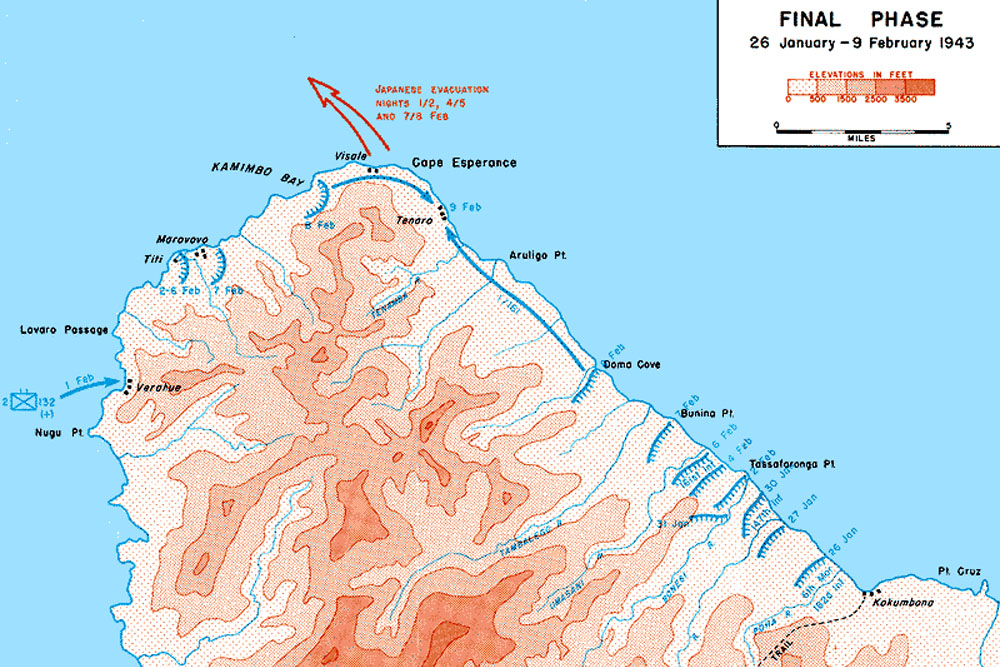

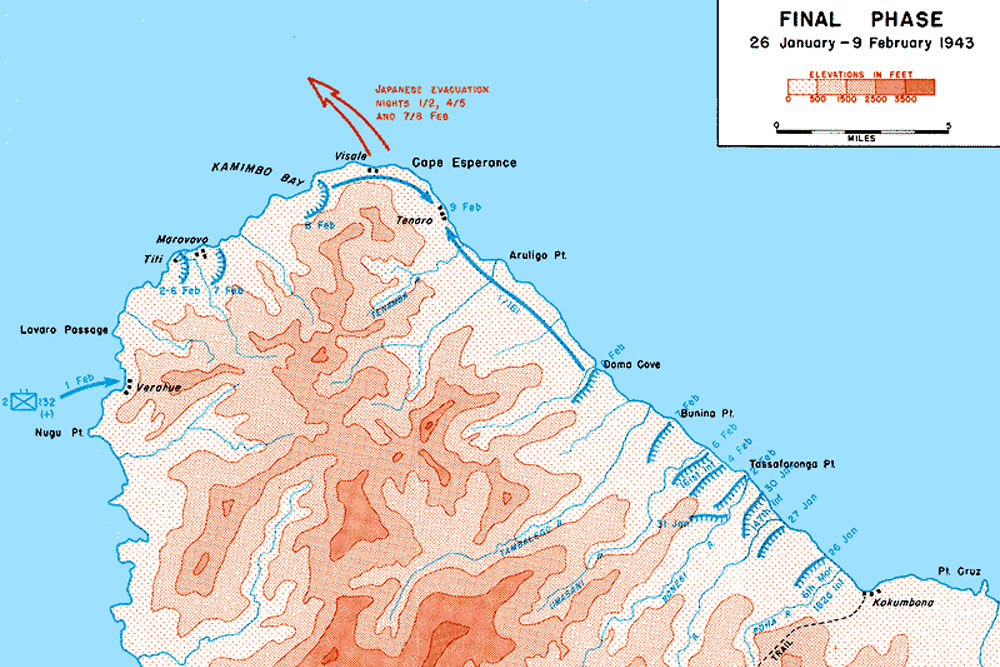

Meanwhile, the Japanese Navy and the Imperial Japanese Army discussed withdrawing troops from Guadalcanal. The army was initially against giving up the strategically located island, but the navy no longer perceived an opportunity to supply the remaining 20,000 troops on the island. On December 28, Emperor Hirohito was personally briefed by representatives of the army and navy. On New Year's Eve 1942, the Japanese emperor formally gave permission to evacuate the troops. The Japanese army and navy leadership immediately began working on plans for the evacuation under the code name Operation Ke.

On January 10, 1943, the American troops on Guadalcanal again opened their offensive against the fortified Japanese positions on Mount Austen and two nearby cliffs, which the Americans called Seahorse and Galloping Horse. On January 23, the three Japanese positions were captured at the cost of 3,000 Japanese and 250 American soldiers. The Marines of the 2nd Marine Division now had a firm grip on almost the entire north coast of the contested island.

On January 14, the Tokyo Express had landed a battalion of troops to cover the retreat as part of Operation Ke. A staff officer from Rabaul conveyed the evacuation message to General Hyakutake. At the same time, Japanese air and naval forces gathered in Rabaul and on Bougainville. They would launch diversionary attacks on Guadalcanal. The American code breakers had noticed the Japanese troop and ship movements but interpreted these as manoeuvres for another combined attack on Henderson Field.

Both General Patch and Admiral Halsey accepted this assumption and on Guadalcanal only a very small part of the American ground forces was deployed to directly combat the Japanese. The rest were put into position to repel the expected attack. Halsey in turn despatched a supply convoy to the island, consisting of four transports protected by four destroyers. Serving as forward protection was Task Force 18, which consisted of the heavy cruisers USS Wichita, USS Chicago and USS Louisville, the light cruisers USS Montpelier, USS Cleveland and USS Columbia, the escort aircraft carriers USS Chenango and USS Suwannee and eight destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Robert C. Giffen. Halsey also maintained a Task Force around the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise approximately 250 nautical miles away from TF 18.

On January 29, 1943, Task Force 18 was attacked near Rennell Island by Japanese fighter planes from the naval base at Rabaul. The escort aircraft carriers were no longer part of the Task Force at that time because they were too slow. At 07:36, both the USS Chicago and USS Wichita were hit by aerial torpedoes. The Chicago suffered heavy damage, but the Wichita was more fortunate as the torpedo failed to explode. The Louisville took the Chicago in tow, but TF 18 could not prevent the damaged heavy cruiser from being attacked again the next day. This time the unfortunate ship was hit by four aerial torpedoes. The destroyer USS La Vallette was also hit and severely damaged. The Chicago was abandoned and sank twenty minutes later. 1,049 people on board the heavy cruiser were rescued, but help came too late for 62 crew members. With the La Vallette in tow, TF 18 returned to Espiritu Santo. The Battle of Rennel Island was the final naval battle of the Battle of Guadalcanal.

Due to the diversionary manoeuvres, Operation Ke succeeded beyond the Japanese Navy's expectations. On the night of February 1, twenty destroyers from Rear Admiral Mikawa's Eighth Fleet evacuated 4,935 Japanese soldiers, mostly from the 38th Infantry Division. On the nights of February 4 and 7, the destroyers took another 5,000 troops from Guadalcanal. A total of 10,652 troops were evacuated. General Patch didn't realize his enemies were gone until the ninth. His message to the US High Command was: "Tokyo Express no longer has terminus on Guadalcanal."

Remaining wrecks of vessels testify to the defeat the Japanese suffered on Guadalcanal. Source: World War Photos

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Consequences of the Battle of Guadalcanal

After the perfectly executed evacuation of Japanese troops from Guadalcanal, the Americans quickly expanded the hard-won island itself and nearby Tulagi into bases for the further American advance in the Pacific. In addition to Henderson Field, three more airfields were constructed on Guadalcanal and naval ports with extensive facilities appeared on Tulagi and Florida. Furthermore, the relentless efforts by the Japanese to retake Guadalcanal had weakened their offensive power in other theatres of war. This became painfully clear, especially in New Guinea, when an Allied counterattack on Buna and Gona resulted in a Japanese defeat. From then on, the Japanese were forced onto the defensive. In June 1943, the Allies launched Operation Carthwheel. The objective of this operation was to isolate the highly strategic naval base of the Japanese in Rabaul. By disrupting or eliminating all lines of supply, removal and communication, the Allies managed to sideline Rabaul without fighting a bloody battle. As a result, MacArthur's land campaigns and Nimitz's Island Hopping campaign had much less to fear from the Imperial Japanese Navy than the Japanese had hoped.

After the Japanese evacuation, the Americans were able to freely put ashore their supplies. Source: World War Photos

The US Navy's aircraft carrier strength was tested to the limit by the Battle of Guadalcanal. Just after the battle, the US Navy could only dispose of the USS Saratoga and USS Enterprise. The latter ship had been damaged so often in early 1943 and had so much overdue maintenance that it would not have been usable for much longer. The gap between the delivery and operational deployment of the Independence-class and the Essex class (1942) aircraft carriers was forced to be filled with escort aircraft carriers of the Bogue class (1941) and the Sangamon class (1942).

Definitielijst

- Island Hopping

- American strategy of conquering island after island to recapture the territory in the Pacific lost during World War 2.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Epilogue

The Battle of Guadalcanal turned out to be an accumulation of superlatives. The battle was a very complicated combination of combat on land, at sea and in the air that the Americans had not yet mastered. Yet the battle on land was the first won by the Americans. The supply of troops and supplies led to major naval battles in which the Imperial Japanese Navy repeatedly emerged as the tactical victor. However, strategically speaking, the Americans always came out on top. Furthermore, the battle required the first large-scale amphibious landings by both the Japanese and their opponents. The American air superiority made these landings much easier for them to carry out, but due to the persistent Tokyo Express, the initiative always lay with the Japanese. Moreover, no seabed was so densely littered with shipwrecks as Ironbottom Sound.

Due to their superior long-range torpedoes and their excellent night fighting skills, the Japanese dominated during the naval battles of the Battle of Guadalcanal. This only changed when the US Navy finally discovered that the many failed attacks by their submarines were caused by torpedoes that often refused to explode. Only when the submarine commanders had demonstrated and proven this did the US Navy resolve this technical deficiency. The US Navy also became increasingly improved their night fighting skills during the Battle of Guadalcanal. Until such time, the Japanese failed to finish off enemy fleets because they feared suffering losses. The Americans were less afraid of this because they knew that hundreds of ships were under construction.

The loss of ships and aircraft ultimately proved not to be decisive for the Japanese's eventual downfall. The loss of experienced pilots, which had already occurred during the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway, was much more decisive. During the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Imperial Japanese Army also lost tens of thousands of experienced and hardened infantry soldiers. Such irreversible sacrifices proved to be the beginning of the end for the expansion of the Land of the Rising Sun.

The developments in the Battle of Guadalcanal were widely reported in the American press. The Americans needed heroes to keep their morale high and the Pacific theatre provided lots of them. Admiral King had shown that the US Navy did not have to play second fiddle during World War II and volunteers back home were lining up to join the proud American naval forces. Thus, the victory of the Battle of Guadalcanal became a huge morale boost for all Americans. This psychological victory could not be measured in numbers of men, ships or aircraft, but it undoubtedly contributed to the eventual outcome of the Second World War.

After the Battle of Guadalcanal was won, various campaigns - such as these Women Appointed for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) - were launched in the United States to recruit all kinds of war volunteers. Source: Public domain

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Midway

- Island in the Pacific where from 4 to 6 June 1942 a battle was fought between Japan and the United States. The battle of Midway was a turning point in the war in the Pacific resulting in a heavy defeat for the Japanese.

Timeline of the Battle of Guadalcanal

| Battle | Allied forces | Allied losses | Japanese forces | Japanese losses |

| Occupation of Tulagi and Guadalcanal, August 8, 1942 | 19,000 Marines and supporting troops | 122 men, 19 aircraft, transport USS George F. Elliot | 1,500 engineers and soldiers | 876 men, 36 aircraft |

| Battle of Savo Island, August 8-9, 1942 | Heavy cruisers USS Astoria, USS Quincy, USS Vincennes, USS Chicago, HMAS Australia, HMAS Canberra, light cruisers USS San Juan, HMAS Hobart, 8 destroyers, 23 transports | 1,007 crewmen, heavy cruisers USS Astoria, USS Quincy, USS Vincennes, HMAS Canberra, destroyer USS Jarvis | Heavy cruisers Chokai, Furutaka, light cruisers Tenryu, Yabari, 1 destroyer | 200 crewman, heavy cruiser Kako |

| Battle of the Tenaru River, August 21, 1942 | 3,000 Marines | 44 Marines | 917 infantry | 789 infantry |

| Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands, August 24-25, 1942 | Aircraft carriers USS Enterprise, USS Saratoga, USS Wasp (CV-7), 1 battleship, 4 cruisers, 11 destroyers, 176 aircraft | 90 crewmen and pilots, 20 aircraft | Aircraft carriers Shokaku, Zuikako, Ryujo, 2 battleships, 12 cruisers, 25 destroyers, 1 seaplane mothership, 4 patrol vessels, 3 transports, 177 aircraft | 290 crewmen and pilots, light aircraft carrier Ryujo, destroyer Mutsuki, 1 transport, 75 aircraft |

| Battle of Edson’s Ridge, September 12-14, 1942 | 12,500 Marines and commandos | 104 troops | 6,217 infantry | 800 infantry |

| Battle of Cape Esperance, October 11-12, 1942 | Heavy cruisers USS San Francisco, USS Salt Lake City, light cruisers USS Boise, USS Helena, 5 destroyers | 163 crewmen, destroyer USS Duncan, 2 seaplanes | Heavy cruisers Aoba, Kinugasa, Furutaka, 8 destroyers, 2 seaplane motherships | 454 crewmen, heavy cruiser Furutaka, destroyers Fubuki, Natsugumo, Murakumo |

| Battle of Henderson Field, 23-26 October, 1942 | 23,000 Marines and infantry troops, artillery | 80 troops, 3 aircraft | 10,000 infantry and 10,000 reserve troops, artillery, 10 light tanks | 2,200 to 3,000 infantry, 14 aircraft, 10 light tanks |

| Battle of Santa Cruz Islands, October 25-27, 1942 | Aircraft carriers USS Enterprise, USS Hornet (CV-8), 1 battleship, 6 cruisers, 12 destroyers, 136 aircraft | 266 crewmen and pilots, USS Hornet (CV-8), destroyer USS Porter, 81 aircraft | Aircraft carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku, Zuiho, Junyo, 4 battleships, 10 cruisers, 25 destroyers, 199 aircraft | 400 to 500 crewmen and pilots, 99 aircraft |