The War at Sea

By Francis E. McMurtrie.

The War Illustrated, Volume 8, No. 184, Page 102, July 7, 1944.

Though certain of the details have still to be filled in, enough is now known of the Allies invasion of Normandy to make it plain that it is the greatest as well as the most successful combined operation that has even been undertaken. After all their efforts to ascertain where the blow was most likely to fall, the Germans were in the end taken by surprise. Over 4,000 ships of every kind, together with immense numbers of landing craft, were able to proceed across the Channel, breach the enemy coast defences and land large armies where desired, all without appreciable interference by the enemy sea or air forces.

This vast armada must have been collected from ports all over the United Kingdom, thought the greater proportion was concentrated beforehand in southern harbours. To ensure surprise, it may be assumed that the use of wireless was restricted to a minimum; thus communications needed to be severely limited. Everybody concerned seems to have known exactly what had to be done, so that the operation of crossing the Channel and landing the troops was carried through without a hitch.

Superior sea power was the foundation on which this success was based. Not only was ample tonnage available, in the shape of merchant vessels and landing craft, to transport the troops to the beaches, but very strong naval forces were provided for duty as escorts, for the bombardment of German gun emplacements, and to clear the minefields which presented the most dangerous obstacle of all. After the landings had been completed, these naval forces continued to support the invasion by shelling enemy concentrations of tanks and artillery, and protecting the sea supply routes against attack by enemy light craft. In fact, sea power played just as important a part as it did in the North African and Sicilian landings.

In Washington it has been revealed that the contribution of the United States Navy to the operation numbered 1,500 ships, comprising the battleships Nevada, Texas and Arkansas, the heavy cruisers Augusta, Quincy end Tuscaloosa, over 30 destroyers, and large numbers of destroyer escorts, transports and landing craft. It should be explained that “destroyer escort” is the official rating of an American type of escort vessel, corresponding to British frigates of the “Captains” class.

British warships numbered about twice as many as American, and are known from Press reports to have included the battleships Nelson, Rodney, Warspite and Ramillies; cruisers Ajax, Apollo, Arethusa, Argonaut, Belfast, Bellona, Black Prince, Ceres, Danae, Diadem, Enterprise, Frobisher, Glasgow, Hawkins, Mauritius, Orion, Scylla, and Sirius; destroyers Algonquin, Ashanti, Beagle, Brissenden, Eskimo, Haida, Huron, Javelin, Kelvin, Melbreak, Scourge, Sioux, Tartar, Urania, Versatile, Vidette, Wanderer and Wrestler; the monitor Roberts; frigates Duff, Stayner, Tyler and Torrington; and the auxiliaries Glenearn, Glenroy, Hilary, Prince David and Prince Robert. Of these ships, the Algonquin, Haida, Huron, Sioux, Prince David and Prince Robert belong to the Royal Canadian Navy, the growth of which since 1939 has been absolutely phenomenal.

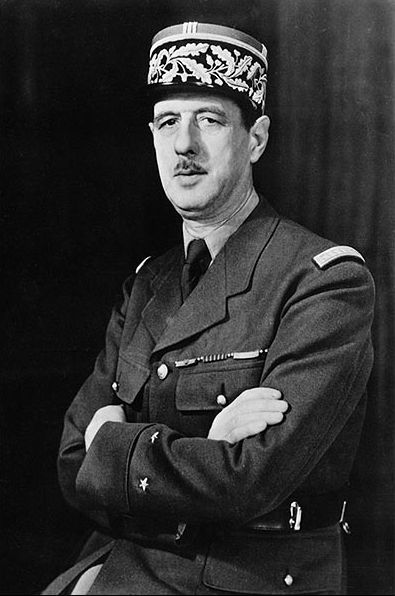

More than 200 minesweepers of various types formed an important element of this fleet, together with a number of warships belonging to our European Allies. There were the French cruisers Georges Leygues and Montcalm, with the destroyer La Combattante, in which General de Gaulle took passage for his visit to Normandy; the Polish cruiser Dragon and destroyers Blyskawica, Krakowiak and Piorun; the Norwegian destroyers Glaisdale, Stord, and Svenner; and the Dutch gunboats Flores and Soemba. Two Italian destroyers are also believed to have been present.

One of the surprises of this operation has been the rapidity with which naval guns have knocked out shore ones. While there is no doubt that fire control methods have improved out of all knowledge since the Belgian coast bombardments of the 1914-18 war, it is still true that a gun mounted in a battery on shore has definite advantages over on in a ship. There is a limit to the amount of armour that a warship can carry, but a fort can be protected to any extent desired. A ship can be sunk, but a silenced battery can be re-established, repaired or re-manned.

Yet in the last few weeks the naval gun has triumphed every time. One reason for this has been the thoroughness of air reconnaissance, enabling the exact position of every gun emplacement to be ascertained, so that it can be wiped out by an overwhelming concentration of fire. Spotting of the fall of shot from the air has been developed till it is almost an exact science, depending largely upon very carefully co-ordinated communication by signal between ship and observer. Previous experience in Italy and elsewhere has also borne good fruit. Having said all this, it still remains a fact that the gunnery of the Allied warships has been exceedingly good, testimony to the keenness and trained efficiency of naval officers and men. That these statements are in no degree exaggerated may be judged from the chorus of praise for the achievements of the naval guns from the Allied armies and from independent Press observers afloat and ashore.

Up to the time of writing, no news has come of Allied naval losses, beyond the statement that two U.S. destroyers were sunk, and reports of landing craft wrecked. Though German claims in this connexion may generally be disregarded as exaggerated out of all proportion to the truth, it is significant that on this occasion they have been unusually modest. Their own losses, on the other hand, have been severe, having regard to the few ships at their disposal. On June 7 three destroyers were attacked by Coastal Command aircraft in the Bay of Biscay. One of these was set on fire, a second slowed down perceptibly, and a third had stopped when last seen. Attacks were also made on the same date upon coastal craft of the type which the Germans call S-boats, but which for no logical reason are commonly referred to as E-boats. Two of these were sunk and a third may have shared their fate.

A day later another enemy m.t.b. was attacked with rockets by fighter aircraft and was almost certainly destroyed. Off Ushant a force of German destroyers was brought to action by six British destroyers; one of the enemy ships was torpedoed and sunk and a second was driven ashore. In other encounters more than a dozen m.t.b.s. and motor minesweepers and several armed trawlers were lost, while air attacks on the harbours of Havre and Boulogne are believed to have accounted for a good many more. Some of these losses have been admitted by the enemy. We lost a motor torpedo boat in one engagement.

Previous and next article from The War at Sea

The War at Sea

There is no doubt the complete success of the Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, was due to thorough preparation and the use of overwhelming force. Lack of these two essentials had much to d

The War at Sea

Finnish insistence on fighting to the last ditch for the benefit of Germany must inevitably affect the naval situation in the Baltic. Already the enemy, in accordance with the pact made by Ribbentrop

Index

Previous article

The Battle Fronts

It is high time to stop using the term Second Front. It has long ceased to be accurate, though it conveniently defined out strategic aims. Now that those aims have taken concrete shape we should, I

Next article

With the 'Suicide Squads' Who Cleared the Way

An 80-mile breach in the vaunted West Wall on the Normandy coast lies at the back of our Armies in France. It can now be revealed how, in fantastic circumstances, British scientists stole the beach