Introduction

"Don't listen to anyone who tells you that you can't do this or that. That's nonsense. Make up your mind, you'll never use crutches or a stick, then have a go at everything. Go to school, join in all the games you can. Go anywhere you want to. But never, never let them persuade you that things are too difficult or impossible."

This quote comes from an interview Douglas Bader gave after the war. The statement gives a good impression of this special British pilot of Fighter Command. Douglas Bader is one of the best known R.A.F. pilots of World War Two. He earned this reputation partly for the number of enemy aircraft he shot down during the war but also because he achieved all this without legs.

Images

Childhood years

Douglas Robert Steuart Bader was born February 21st, 1910 in St. John’s Wood, London. His parents were Frederick Robert Bader and Jessie Bader. He had an older brother, Frederick (Derick) who would die in an accident in 1935. Shortly after his birth, Douglas contracted measles from which he recuperated quickly though. A few months after his birth, his parents returned to India where his father was employed as an engineer. As his parents thought the local climate would be unhealthy for Douglas, he was left behind with familiy members on the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea.

At the age of two, his parents had him come to India after all but his stay in this former British colony was of short duration. In 1913, Douglas’ father decided to return to England in order to study law. The familiy settled in Kew, a suburb of London. In 1914, Frederick Bader was drafted into the British army. As an officer in the Royal Engineers, he left for France. During World War One he fought on the Western Front. After the war, Major Frederick Bader stayed in France due to his work for the War Damage Commission. He died in 1922 in a hospital in St. Omer of complications of previous injuries from shrapnel he had sustained in Arras in 1917.

People who knew him at that time described his character as lively and impulsive, he could not resist any challenge. Assumably he had a bad childhood. Bader often quarelled with his older brother and his mother often placed him at a disadvantage. During his years at boarding school in Oxford, Douglas displayed a talent for sports. He played rugby and cricket, practised boxing and regularly belonged to the best. He also did well in the rest of the subjects although he never exerted himself overmuch. His school records often stated his results were not bad in themselves but that he would achieve more if he would perform better.

After the death of her husband, Jessie married the priest William Hobbs and the family settled in Sprotborough near Doncashire in Yorkshire. Hobbs never managed to play the role of father to Douglas. His mother showed little interest in raising her son and often shoved him off to family. In 1923, Douglas stayed with his aunt Hazel Bader and her husband Flight Lieutenant Cyril Burge, at that time adjutant at the R.A.F. College in Cranwell. Douglas Bader was very much impressed by the cadets whose sportmanlike attitude he admired. From that moment on, he also showed a keen interest in aircraft.

After primary school, Bader attended St. Edward’s School, a boarding school in Oxford, from the fall of 1923 onwards. Here, sports appealed to him very much as well. He played on the rugby and cricketteam of the school and excelled in athletics as well. He had more trouble with the other subjects. He did show interest in Greek, Latin and history and he did rather well in those. He had much trouble with mathematics and did little to earn higher marks in this subject.

Images

Training in the R.A.F.

Early 1928, Bader thought long and hard about what to do after graduation from St. Edward’s. Finally he decided to join the R.A.F. To this end he had to attend R.A.F. College in Cranwell, Lincolnshire. There was a problem though. To be able to take the two year course, a fee of 150 pounds per year had to be paid. His mother and stepfather could not afford such a large amount. Luckily for Bader, St. Edward’s offered a solution. Each year, the school granted a limited number of scholarships to those boys who wanted to become cadets in the army, the navy or the air force. To be eligible for this, Douglas had to study more intensively as there were dozens of boys who were interested in a military career and only the top six were eligible for the R.A.F. scholarship.

Partly because he was given extra coaching in mathematics, enabling him to pass the final exams at St. Edward’s, he managed to get his scholarship. The entrance examination for the R.A.F. also posed few problems. Only the medical examination seemed to be an obstacle. Due to the fact Douglas had suffered from reumatic fever, his blood pressure was rather high. The doctors on the examination board considered disqualifying him but eventually they gave him permission to start at Cranwell.

In the spring of 1928, Douglas reported at Cranwell. He did very well in the practical side of the training. He soon mastered flying the training aircraft, the AVRO 504 and within a very short time he started experimenting with aerobatics. He had more problems with the theoretical part of the training. Douglas had never really liked to study and again he could set himself to it with difficulty. He also frequently violated the rules of the course. He arrived later at the base than permitted, he possessed a car which was forbidden and he was even apprehended once by the military police for recklessly riding his motorbike.

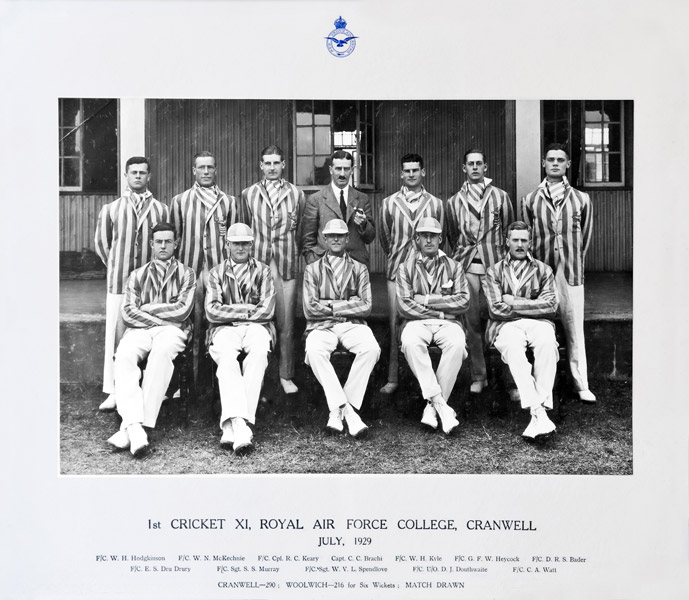

After a year, an interim exam was held and Bader ended third last. He was officially reprimanded by the commander of his training squadron. After a talk with station commander Air vice-Marshall Frederick Halahan, he began to work harder and his marks increased considerably. He even was appointed second in command of his training squadron. After final exams, Douglas came out second best of his class. He was considered: "courageous, skillful and stubborn." His flying skills were valued at above average, the second highest qualification. During his training and service in the R.A.F. , Douglas Bader kept busy in sports. He played on the hockey- cricket- and the rugbyteam representing the R.A.F. . He also was a meritorious pugilist.

Images

Service in the R.A.F. and his accident

On completion of the two-year course, Pilot Officer Douglas Bader was posted to No. 23 Squadron at Kenley Airfield in Surrey on July 26th . This squadron was one of the last units that was still equipped with the Gloster Gamecock. This biplane fighter from 1925 really needed to be replaced mainly because it was very unsafe and a number had crashed. The Gamecock’s advantage was that it was very manoeuvrable and therefore well suited for aerobatics. Douglas still loved aerobatics and he was so good at it that in 1931 he was selected, along with his squadron leader Harry Day, to participate in the Hendon Air Show where the team assumably made a good impression.

In the course of 1931, the Gamecocks of No. 23 Squadron were replaced by Bristol Bulldog fighters. These aircraft were far better technically than the Gamecock but did have the disadvantage of being unstable. It was therefore quite dangerous to perform stunts with this aircraft. Douglas Bader loved to fly low and continued doing aerobatics. For this he was cited by his squadron commander whereupon he promised to be more careful.

On December 14th , 1931, during a visit to the Reading Aero Club at Woodley Airfield in Berkshire, a few pilots challenged Bader to do a few aerobatics. Initially he refused but when it was insinuated that he was afraid, he rose to the challenge. After having performed a few aerobatics, things went dramatically wrong. He struck the ground with his left wing tip and the plane crashed. His legs got trapped and the crumpled cockpit had to be broken open before Bader could be extricated. He was speedily transported to the Royal Berkshire Hospital. Dr. J. Leonard Joyce, at the time one of the best surgeons in Great-Britain happened to be in the hospital and immediately operated upon Bader. His right leg was all but torn off and had to be amputated. His left shinbone was shattered and Joyce hoped this leg could be saved but when the leg became infected and showed signs of gangrene, it had to be amputated as well.

As a result of the intensive operations and loss of blood, Douglas Bader was in a deep shock; the physicians doubted whether he would live through it and his family was warned more than once that Bader was dying. From Christmas 1931 onwards, his condition stabilised though and he began to recover slowly. He continued to suffer from phantom pain which could only be suppressed by large doses of morphine. Notwithstanding, Douglas Bader retained a certain form of British humor. When Joyce told him he was sorry he had not been able to save his legs, Bader is said to have remarked: "That is allright, doctor. I’ll get myself a pair of longer legs. I have always wanted to be somewhat taller"

January 15th, 1932, Douglas Bader was allowed to get out of bed for the first time. Using crutches and a walking aid for his left leg, he managed to walk again. Following a long period of recuperation, Douglas was transferred to R.A.F. Hospital in Uxbridge, West London in April 1932. There he met Marcel Dessoutter, an airplane designer who had crashed during a testflight and had lost a leg in the process. After his accident, Dessoutter and his brother Robert had started a company that developed various protheses. Douglas received two artificial legs from this company. The problem was that Bader had lost both legs, a rare occurrence.

Despite his handicap, Douglas gradually did better, mentally as well as physically. Normally it takes six months for someone who gets a prothesis, to get used to it. To the surprise of everyone, Douglas managed to walk relatively normal within a few weeks. He also managed to drive a car again, albeit in an adapted vehicle. In the middle of June he went on sick leave and left the hospital at Uxbridge. His urge to return to flying was very great. He stated he would rather die than leave the R.A.F.

Images

Return to the R.A.F. and discharge

In June 1932, Bader had a talk at his own request with Sir Philip Sassoon, at that time Undersecretary for Air about a possible return to the R.A.F. Despite his doubts, Sassoon gave in eventually and Bader received permission to make some testflights in an AVRO 504 training aircraft. He felt this training flight went extremely well and he made more flights during the following days. Subsequently he underwent an official examination and was considered medically fit for flying in Europe although he had to take a course at the Central Flying School. Here he flew a number of aircraft including the Bristol Bulldog. The instructors at the C.F.S. were very pleased with his performance. Bader was called up for another medical examination and he was convinced he would be fully qualified again. To his great shock, he was informed he could not be qualified for air service because there was nothing in King’s Regulations that covered his case.

In November 1932, Bader was posted to No. 19 Squadron at Duxford, Cambridgeshire. Here he got a job in the department of motor transport. He thought the job very boring and deadly dull. At the end of April 1933, he was officially discharged from the R.A.F. for bad health. He was totally demoralised. He received a pension and a disability allowance of 300 pounds per year in total which was not too bad. Apart from his studies at Cranwell, Bader had not had any other vocational training though which made him ineligible for many jobs. Moreover there was little work due to the economic crisis of the 30s. He contacted the mediation office for officers. That office found him a job with the Asiatic Petroleum Company (the present Shell). Here he would be employed during the next six years in a desk function in the aviation department, selling petrol and other oil related products.

On October 5th, 1933 Bader married Thelma Edwards, a waitress he had met during his period of recuperation in Uxbridge where she worked in a local tea room, the Pantiles. On October 5th, 1937, this marriage was consecrated officially. Douglas Bader continued practising sports. Playing rugby was no longer possible but he still played cricket and also started playing golf. Despite his new civil job, he retained the urge to go back to flying. He repeatedly wrote letters of application to the Air Ministry but these were steadfastedly rejected.

Images

Back in service

In April 1939, with the threat of war increasing, Air vice-Marshall Charles Portal, head of the personnel department of the R.A.F. wrote:’ ….should a war break out however, you can almost be sure we will gladly make use of your services as a pilot within a short time, provided the physicians give their consent." On September 3rd, 1939, the day Great-Britain and France declared war on Germany, Bader immediately wrote to Portal’s secretary. Early October he received a telegram from the Air Ministry to the effect he had to report to the selection committee. He was declared medically fit but nonetheless he was informed he was eligible for a posting to ground service only. Air vice-Marshall Halahan, commander of Cranwell at the time Bader was stationed there, intervened for him and managed to have Bader examined by the Central Flying School at Upavon, Wiltshire. He reported there on October 15th . At the end of November he was declared capable to execute operational flights. He was posted to the C.F.S. for a refresher course on new types of aircraft.

On November 27th, 1939, Bader flew solo in an AVRO Tutor for the first time. During the following days, he flew other types of aircraft including the Fairey Battle, a light bomber and the Miles Master in preparation for the Spitfire and the Hurricane. He graduated at the end of January 1940. His flying skills were judged as excellent. On February 7th, 1940, he was posted to No. 19 Squadron at R.A.F. Duxford near Cambridge. Here he flew the legendary Supermarine Spitfire for the first time. Squadron commander was Geoffrey Stephenson, an old friend of his from his Cranwell period. Between February and May 1940, the squadron was involved in protecting convoys at sea and training attacks. Douglas Bader did not agree with the existing doctrines. He had more faith in simultaneous attacks by two or three aircraft, launched from great height and using the sun as cover. Due to his fine capacities, Douglas was soon appointed section leader.

In this period he crashed his Spitfire at take off because he had forgottten to set the propellor pitch correctly. His aircraft was a total write off and his protheses were severely damaged but physically, Bader was allright except for a head wound. He had to report to the station commander, Air vice-Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory, the future commander of Fighter Command. He expected to be reprimanded and got one but he was also told he was appointed flight commander of No. 222 Squadron R.A.F. and that he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant. 222 Squadron was also based at R.A.F. Duxford and was commanded by Herbert "Tubby" Mermagen, also an old friend of Bader’s. Bader trained his men in his own specific manner, spending much time on individual attacks.

Images

Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain

May 10th, 1940, the Germans launched a massive offensive in the west, Fall Gelb, targeted at the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg and France. Bader was delighted the war had broken out. To his wife, he allegedly had said: "Now we can finally get going." No. 222 Squadron however was not deployed on the European continent yet and continued being involved in convoy protection and training flights for the next few days. May 28th, the squadron was transferred to R.A.F. Kirton-on-Lindsey in Lincolnshire and subsequently to Hornchurch in Essex where it would remain until August 1940. The unit was to fly patrols over Dunkirk and protect the vessels involved in the evacuation of the Allied troops from France (Operation Dynamo between May 27th and June 4th ). During one of these patrols, on June 1st, Bader managed to down a Messerschmitt Bf 109, his first kill. During another patrol he also destroyed a Heinkel He 111, according to some sources.

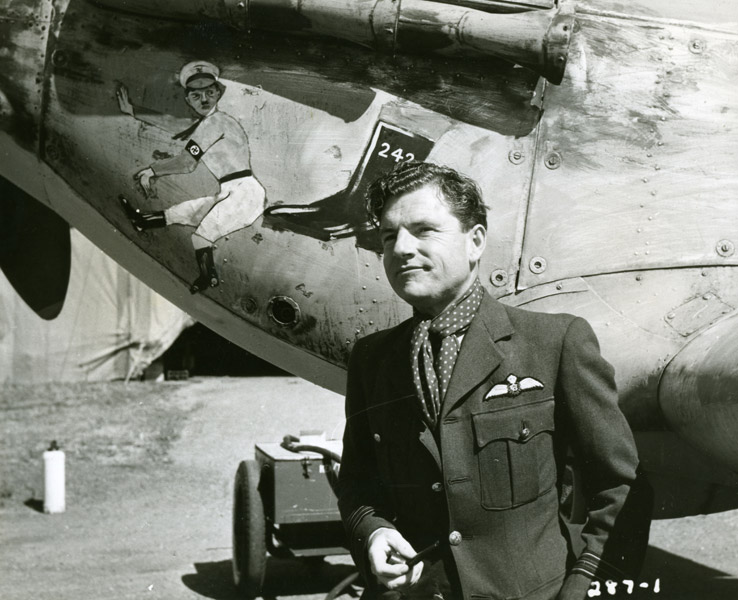

On June 4th, 1940, Bader flew his last patrol over Dunkirk. He crashed with his Spitfire during a landing in bad weather. He was allright himself but his plane was severely damaged. He had to report to Leigh-Mallory again. He feared the worst but instead he was told he was appointed Acting Squadron Leader of No. 242 Squadron, a unit based on R.A.F. Coltishall, Norfolk, equipped with Hawker Hurricanes and mostly consisting of Canadians. The unit had suffered heavy losses during the battle for France and had had to leave all reserve parts and tools behind on the European continent. June 28th, 1940, Bader reported to Coltishall. Initially, the Canadians had little faith in a disabled squadron leader. When Bader showed them he could handle his aircraft very well, they accepted him gradually.

Bader effected a few organisational changes. He also saw to it that the material of the squadron was brought back to normal immediately. In order to achieve this, he sent a terse radio message complaining about the operational status of the unit. He was ordered to report at Fighter Command HQ. He expected serious problems but his action eventually did yield the desired result. Bader showed he lived for his unit. During the first months, he slept in the same barracks with his men and always stood squarely behind them. He also went out with his men (Douglas seldom drank alcohol but he always smoked a pipe). Because of this and by intensive training, he managed to boost the morale of the unit. On July 9th, 1940 he was able to report that No. 242 Squadron was fully operational again.

July 10th, 1940, the Battle of Britain started in earnest. The Germans attempted to gain air supremacy over England, prior to their planned invasion. No. 242 Squadron was part of No. 12 Group R.A.F. In the first phase of the battle, this group was kept in England and deployed to protect the industry in the Midlands. No. 11 Group took on the Luftwaffe. Bader could not stand being kept grounded while the R.A.F. suffered heavy losses.

July 11th, No. 242 Squadron was ordered to scramble because an enemy aircraft had been spotted. Bader refused because he considered it irresponsible to fly because of the dense clouds. HQ kept urging and finally Bader decided to take off himself. After having searched for a while, he sighted a Dornier Do 17, a German bomber over the coast of Norfolk. He fired at the plane a few times but could not judge whether he had placed any hits. Later, the Royal Observer Corps reported a plane had been seen crashing into the sea whereupon Bader was credited with the Dornier after all.

On August 30th, after Bader had shot down another Dornier and two Messerschmitts, 242 Squadron was ordered to move to R.A.F. Duxford south of Cambridge because intelligence had indicated that a German attack was to be expected. Initially, the squadron could not find any enemy aircraft until a group of 14 bombers with about 30 fighters was intercepted that was attacking R.A.F. North Weald. During the ensuing engagement, Bader managed to shoot down two Messerschmitt Me 110s. The squadron as a whole destroyed 12 German aircraft and damaged quite a few more. The squadron suffered no losses itself. In this engagement, Bader had experimented for the first time with the tactic to attack from great height, preferably out of the sun, diving down on the enemy formation and breaking it up whereupon the enemy aircraft had to be destroyed in individual dog fights.

The success of August 30th indicated that his tactic was effective but Bader was of the opinion he could have achieved more if he had had more aircraft at his disposal. Bader talked to Leigh-Mallory and he made two extra squadrons available to him, No. 19 and No. 310 (Czech) Squadron to put his theory to the test. The aircraft were based at Duxford. Bader trained his men accordingly and on September 5th, he managed to get all aircraft in position within five minutes. On September 7th, Bader was offeerd the chance to test his theory again. The Hurricanes and Spitfires took off but he failed to get the formation in position on time, hence the fighters were still flying too low when they intercepted the German formation and their position of attack was unfavourable. Moreover the British formation was widely dispersed. Douglas Bader mananged to shoot down a Messerschmitt Me 110 but his own Hurricane came under fire from a Messerschmitt Bf 109. Bader landed his severely damaged aircraft with great difficulty. Afterwards it became evident that the Wing (a large formation of aircraft consisting of three or more squadrons) had achieved success: 11 enemy aircraft had been destroyed while the Britsh had lost only two.

In the days that followed, the Wing of Douglas Bader launched still more successful attacks, destroying 20 enemey aircraft. On September 14th, 1940, Bader was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Leigh-Mallory also allocated two squadrons to his Wing: No. 302 (Polish) equipped with Hurricanes and No. 611 Squadron R.A.F. equipped with Spitfires. This so called Big Wing saw action for the first time on September 15th, 1940. The Wing intercepted an attack on London and destroyed 52 German planes. The unit postponed its attack until the escorting Bf 109s were forced to return to their bases in France for lack of fuel. The Dorniers, Heinkels and Junkers were then easy prey. On September 18th, something similar happened: the Duxford Wing (the unofficial name of the unit) destroyed 30 bombers. Bader himself shot down a Dornier Do 17 and a Junkers Ju 88.

Afterwards it became evident that at that moment, the Battle of Britain had in fact been won by the R.A.F. After mid September, Hermann Göring (Bio Göring), supreme commander of the Luftwaffe, suspended the massive bombing attacks on London. Henceforth he only dispatched groups of Messerschmitt Bf 109s to Great-Britain. The German bombers only attacked at night from then on.

On September 27th, the Duxford Wing intercepted a German formation consisting of fighters attacking in daylight. The unit managed to destroy 12 Bf 109s, two by Bader himself. The Wing lost three airplanes. The Duxford Wing is said to have destroyed 152 German aircraft, the unit itself lost 30 pilots and more than 30 planes. Yet the principle of the Big Wing was not undisputed. The supreme commander of Fighter Command, Air vice-Marshall Keith Park for instance opposed the idea and had more faith in smaller formations. One of the disadvantages of the Big Wing was that it took a long time before all the planes were airborne and in position. Although there was discussion about the size of formations, there was no doubt whatsoever about Douglas Bader’s qualities as a fighterpilot and a leader. On January 1941, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and on September 9th, 1941, he would be awarded a Bar to his D.F.C.

At the end of 1940, Leigh-Malory was appointed supreme commander of No. 11 Group. He took 242 Squadron with him and it was based on R.A.F. March Henton.

Images

After the Battle of Britain

After the Battle of Britain had ended in favour of the R.A.F., the British air force set about attacking targets in France. Because of what they had learned from what had happened to the German bomber formations, the British decided to provide their bombers with a very strong fighter escort. No. 242 Squadron was often involved in protecting the Bristol Blenheim bombers attacking targets in France. Small groups of two or three aircraft were als involved in so called sweeps (hit and run attacks). To this end they crossed the Channell and launched attacks on German vehicles in northern France or shipping in the Channell.

On March 18th, 1941, Bader was promoted to Wing Commander and was given command of the Tangmere Wing. This formation consisted of three Supermarine Spitfire Mk II squadrons: No. 145, 610 and 616 and a Bristol Beaufort squadron. In July, the Spitfires were replaced by the Mk Vb variant. The Tangmere Wing was engaged in bombing attacks on strategic targets including trafiic junctions and power stations in Belgium and France. These attacks had a dual purpose. On the one hand they were aimed at inflicting damage on the enemy infrastructure but another and equally important goal was to challenge the German fighters to battle. On June 21st, while escorting bombers, Bader managed to destroy a Bf 109.

Following the start of the German offensive against the Soviet Union on June 22nd, 1941 (Operation Barbarossa) the attacks were intensified in order to force the Germans to pull their air forces back from the Eastern front. During the following flights, Bader succeeded in shooting down three and possibly four Bf 109s. Due to his fine leadership, he was awarded a Bar to his D.S.O. on July 15th, 1941. While he flew in the Tangmere Wing, Bader introduced the finger four formation. The aircraft flew in an inverted V formation with the first section leader at the tip and his wingman on the left behind him. The second section leader flew behind the leader on his right and his wing man at his right behind him again. This formation has become one of the standard formations of both the British and the American air forces.

In July 1941, Bader destroyed four and possibly even six enemy aircraft within eight days. In addition, he damaged another two Bf 109s. He now had more operational missions on his crerdit than anyone else within Fighter Command. Douglas Bader’s call sign was DB which was soon changed into Dogsbody (jack of all trades). His men had such great confidence in him and his leadership that they allegedly introduced the line: "The Beehive Bus Service. Prompt and regular service. Return tickets only."

Douglas Bader began to show signs of exhaustion and his fellow pilots and Leigh-Mallory urged him to take a rest. He did not feel like a rest himself. After continuous pressure he gave in and agreed in early August that he would go on leave in September. At that monent, Bader had more than 20 confirmed kills to his credit. According to his own count that number was even higher.

Images

Prisoner of war

By his demeanor and attitude, Douglas Bader seemed invincible but that came to an end in the summer of 1941. On August 9th, 1941 he and his Wing flew a patrol over France. He got separated from his section and came face to face with six Bf 109s. He managed to shoot down two of them but his plane (according to the general theory) collided with another Bf 109 causing the tail of his Spitfire to be torn off forcing him to bail out. Other theories suggest that Bader had been shot down by another German fighterpilot or that he had fallen victim to the friendly fire of another R.A.F. pilot who mistook Bader’s airplane for a Bf 109. What happened exactly will probably never be known, more so because the wreckage of Bader’s Spitfire has never been examined after the war. After the crash, the Germans took the wreckage away and it was probably scrapped later for spares.

When he tried to leave his plane, Bader right leg became entangled in the cockpit. Lucky for him, the straps of the prothesis were torn off so he could bail out in the nick of time. On landing he was immediately taken prisoner by German soldiers. He was transferred to a hospital in St. Omer, the same place where his father had passed away 19 years before. The Germans found Bader’s right leg in a meadow and managed to repair the damaged prothesis. Also, at Bader’s request, the Luftwaffe sent a telegram to England, asking if a new prothesis could be delivered. After some hesitation, the commanders of the R.A.F. approved and on August 19th, a Bristol Blenheim dropped a new artificial leg near St. Omer.

After Bader had both protheses at his disposal again, he made an attempt at escape. He managed to escape from the hospital and went into hiding in the home of a French couple. The Germans discovered him the next day when they were systematically searching all houses in St. Omer. He was put on a transport to Germany. Later it appeared that a hospital nurse had betrayed Bader’s whereabouts.

Bader spent the rest of the war in various PoW camps for officers. Living conditions in such camps were usually good. Also thanks to the frequent distribution of Red Cross parcels, the prisoners ate well. The guards were predominantly Luftwaffe personnel who were by far not as cruel as those of the SS working in the concentration camps. The Geneva Conventions were adhered to, meaning the officers were exempted from work. The disadvantage of this exemption was that the prisoners fell victim to boredom. This applied to Bader in particular because he was unable to participate in the sports activities of his fellow inmates due to his handicap. His main activity would have been goon baiting, badgering and bullying the guards.

Images

Attempts at escape

The first PoW camp where Bader was interned, was Dulag (Durchgangslager or transit camp) Luft in Frankfurt. Despite his handicap, Bader made several attempts at escape. In Frankfurt he participated in digging a tunnel which was to stretch well outside the fence. Before the tunnel was finished though, Bader was transferred to Oflag (Offizierslager, officers’camp) VIb in Warburg. On January 9th, 1942 he made another attempt at escape. The German guards caught him and his fellow escapees even before they had climbed over the fence and Bader was sentenced to ten days of solitary confinement.

In the spring of 1942, Bader was transferred again, this time to Stalag (Stammlager) Luft III in Sagan in Poland nowadays. Here he met his former squadron leader Harry Day again. Bader was determined to escape. Stalag Luft III is known for a number of attempted escapes that took place there during the war, the best known being the Great Escape in March 1944 which was made into a movie. Before he could start something however, he was transferred again, this time to Stalag Luft VIII-B in Lamsdorf in the southwest of Poland. In August 1942, Bader managed to escape from this camp, along with Flight Lieutenant Johnny Palmer and three others. Bader and Palmer succeeded in disguising themselves as regular soldiers and joined an Arbeitskommando that was put to work outside the camp. He hoped to be able to escape from the outer camp in the direction of Poland. The Germans discovered his escape after a few days and five days later, after a massive manhunt, Bader and Palmer were arrested again. The other three did manage to escape though. Allegedly, the camp commander threatened to confiscate Bader’s artificial legs to prevent him from escaping again but this threat was not carried through.

After his last attempted escape, Bader was transferred to Oflag IV-c on August 18th, 1942. This was located in a medieval castle named Colditz near Leipzig. This camp was reserved for senior Allied officers who had made numerous attempts at escape or were otherwise a security risk. Among the inmates were British, French, Dutch and Poles. In this camp, Douglas met his old friend Geoffrey Stephenson again. The camp was heavily guarded and because of its location in an old fortress on top of a hill, the Germans assumed that escape was impossible. Yet Oflag IV-c is known for the high number of escapes that took place there of which more than 30 were successful, according to some sources. Douglas Bader himself made no more attempts to escape from the camp. He assumed his legs would prove too much of a handicap.

The living conditions in this camp were rather good, although Bader did suffer from boredom. Bader managed to persuade the leaders of the camp to permit him to take a weekly walk outside the camp under guard to make his stay a little more bearable. The camp was liberated on April 15th, 1945 by the American 1st Army. Douglas Bader was flown from Paris to London in an AVRO Anson. Presumably, he asked Fighter Command HQ for permission to fly a few more combat patrols, either in Europe or in the Far East against the Japanese. His request was rejected though.

Images

Retirement from the R.A.F. and civil life

Early July 1945, Bader was appointed commander of the Fighter School at Tangmere. He also was promoted to the temporary rank of Group Captain. After the Second World War, the role of the fighter changed drastically, the emphasise was now far more on support of ground troops. Bader felt uneasy among the new generation of pilots. The highly decorated war veteran blamed them for lacking the efficiency and fighting spirit of the flyers during the Battle of Britain. In turn they blamed him to be old fashioned and unable to handle the modern tactics. On September 15th, 1945, Bader was granted the honour to lead the flypast over London. This was executed by 300 R.A.F. aircraft and served to commemorate the victory of the R.A.F. in the Battle of Britain.

Bader was still homoured by the air force for his achievements during the war. To put an end to the uneasy situation at the Fighter School, Bader was transferred. He was given command over the North Weald Sector of No. 11 Group R.A.F. He was now in charge of 12 squadrons. Bader did not feel at home in the post-war British air force. He also had a hard time accepting the death of his protector and mentor Leigh-Mallory as a result of an aircraft accident in November 1944. In February 1946, Bader was offered a job in Royal Dutch Shell. After having pondered this for a long time, he accepted the offer. On July 21st, 1946, Bader officially left the R.A.F. in the rank of Group Captain. According to his own flight log he had 30 victories to his credit, officially he was credited with 22.5; the half victory meaning that a kill was shared with someone else.

Bader chose Shell because the company had given him a chance after his accident in 1931 and because he was allowed to continue flying in his new job. His official function was chairman of Shell Aircraft Ltd. In this capacity he travelled across the whole world to supervise the actions of this group. In his new civil life he visited numerous hospitals for veterans all over the world. He also delivered many speeches on aircraft related matters. Douglas Bader kept practising sports, in particular golf. He derived much satisfaction from it. A few years after the war he answered the question what had been the greatest sensation of his life with: "That was a few weeks ago when I rounded the golf course at Hoylake (the course of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club) in 77 strokes."

In 1954, Australian writer and fighterpilot during World War Two, Paul Brickhill wrote Bader’s biography, entitled Reach for the Sky. The book turned out a best seller and was made into a movie of the same title two years later. Book and movie granted Bader a veritable celebrity status and were not bad for him financially either. On January 2nd , 1956, Bader was awarded the title Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. In 1976, Bader was knighted by Queeen Elizabeth for services rendered and his dedication to the disabled.

Bader also caused a few controversies, including his defense of Ian Smith, head of the white minority government in the former British colony of Rhodesia (the present Zimbabwe) and because he was a fierce opponent of the independency of Britsh colonies. His preference of re-introduction of the death penalty did not make him popular among many either. He also wrote the introduction to the biography of the famous German Stuka pilot Hanns Ulrich Rudel who had been a dedicated Nazi during the war. During a meeting with Luftwaffe pilots after the war, Bader is said to have remarked: "My God, I had no idea we left so many of you bastards alive."

In 1969, Bader officially retired from Shell. After his retirement he became a member of the Civil Aviation Authority Board. On January 24th, 1971, his wife Thelma died of cancer. Bader married Joan Murray on January 3rd , 1973. The couple took up residence in Marlston, a village in Berkshire. From the end of the 70s onward, Bader’s health deteriorated. On June 4th, 1979, he made his final flight.

During a golf tournament in Ayrshire in August 1982, Bader was struck by a mild heartattack. He recuperated from it rather well. Three weeks later however, on September 5th , 1982 while returning from a banquet in honour of Sir Arthur Harris’ (Bomber Harris, Bio Harris) 90th birthday, he was hit by a stroke again. He did not survive this one and he died at the age of 72.

Images

Epilogue

Douglas Bader has not been forgotten in Great-Britain and beyond. In 1982, family and friends founded the Douglas Bader foundation. In Great Britain, it is dedicated to persons missing one or more limbs.

On August 9th, 2001, the 60th anniversary of his last combat mission, a statue was unveiled in Westhampnett (West Sussex) by his widow Joan in memory of Bader. One of Bader’s artificial legs is part of the collection of the R.A.F. museum in Hendon. Another was sold at an auction in February 2008. In New Zealand, near Auckland International Airport, a street has been named after him. Various schools in Auckland also carry Bader’s name. At his retirement from the R.A.F., Air Marshall James Robb, at the time commander of Fighter Command wrote: "All I can say is that you have set an example that will turn into a legend in the course of the years."

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Wesley Dankers

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!