Index

The assassination attempt on Hitler and the subsequent coup of July 20th, 1944 are among the best known events of the Second World War. The history of the German Widerstand (resistance) is pretty well known meanwhile and the men involved have earned their recognition. Best known of them all is Schwabian aristocrat Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg. He was late in joining the resistance but he managed to inspire and stimulate the conspirators once more by his will power. It was Von Stauffenberg who took the initiatives, it was Von Stauffenberg who drafted the concrete plans for the coup, it was Von Stauffenberg who made the attempt and it was Von Stauffenberg who was in charge of the coup.

Considering the enormous consequences the attempt and the coup would entail, it was extremely remarkable how much depended on one man. Von Stauffenberg actually had to be in Rastenburg to make the attempt and simultaneously be in Berlin to take charge of the coup. Even more remarkable was the fact that Von Stauffenberg was disabled as a result of the grave injuries he had sustained in North-Africa in 1943 but Von Stauffenberg’s presence was essential as he possessed an exceptional personality. No one fostered any hope: the chance of success was slim but it had to be tried. Von Stauffenberg said himself: "I could not look straight in the eyes of the wives and children of the fallen soldiers if I would do nothing to put an end to this senseless slaughter."

As Generalmajor Henning von Tresckow said in the summer of 1944: "The attempt must be made, whatever it takes. Should it fail, action must be taken in Berlin anyway. Then it does not come down to practical issues any more but to the fact that the German resistance has taken it upon itself to cast the first die before the world and history. Apart from that, anything else is unimportant"

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Resistance against Hitler

Adolf Hitler became Germany’s "legal" chancellor in 1933. After the failed coup in 1923 he had chosen a road to power which at least had a semblance of legality. As early as 1933 though, there were those who actively resisted Hitler, mostly as individuals. A focal point was needed which could function as a nucleus around which the resistance could take shape as a single person cannot lead a coup d’état. Just eliminating the leader is insufficient in this case. The ground should be prepared meticulously within the army and the country’s leadership in order to make the entire country accept the transition of power as a fact. A small circle of confidants must be formed. They must establish a provisional government that can take over the military and civil administration as soon as the time came.

During the 12 years under the Nazi regime, the resistance in Germany would revolve around the army. This was the only armed power within the state that could oust the Führer forcibly. Hitler was aware of this, hence all members of the armed forces were obliged to pledge an oath of alliance to him on August 2nd, 1934. Yet this oath was to pose a perennial obstacle to the establishment of a wide spread resistance within the army. Many men felt like a double traitor, to the chosen leader of the fatherland as well as to Hitler. Those who did join the resistance did so because they were convinced of Hitler’s illegal seizure of power being a more serious act of treason than bringing down the Führer.

One of the first military conspirators was naval officer Wilhelm Canaris. As Kapitän zur See he had been appointed chief of the military intelligence service – the Abwehr - in January 1935. His deputy was Oberstleutnant Hans Oster, an army officer. They liked each other and agreed that Hitler had to be removed as soon as possible. In the 30s, the army expanded and the Abwehr expanded with it but in the meantime, Canaris and Oster secretly formed a small group of followers. Both within and outside the army, they found men in influential positions whom they could trust.

One of them was General der Artillerie Ludwig Beck, since July 1935 Chief of the General Staff. He was a highly gifted and educated man but unable to make decisions swiftly and by intuition; moreover his health left much to be desired. He discovered he could not support Hitler’s plans for a war of aggression and took the view that Germany was not yet ready for a large scale conflict. Outside the army, followers were recruited as well. Ulrich von Hassell, former Ambassador to Rome, came from the Corps Diplomatique. After his discharge he had little to do and had frequent contacts with various members of the resistance. He was a courageous man but no real conspirator. With the arrival of Dr. Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, former Mayor of Leipzig, a different sort of man joined the conspiracy. He was intelligent but could fly into an enormous rage when, in his opinion, something went wrong. His overt criticism of Hitler sometimes made other members shudder. He became the roving ambassador of the resistance.

Other prominent men who were won over to the resistance in this period, were lawyers Hans von Dohnanyi, Johannes Popitz, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, former Reichsbankpräsident Hjalmar Schacht, diplomat Adam von Trott zu Solz, politician Julius Leber, reverend Dietrich Bonhoeffer and various high ranking army officers.

In 1938 however, Beck retired. In consequence, only Canaris still had an influential position although he had no authority over the army either. Beck was succeeded by General der Artillerie Franz Halder. He did not oppose the resistance and provided useful information.

There were now two possibilities to get rid of Hitler: arrest and try him for treason or eliminate him by murder and commit a coup. Halder came up with the idea to arrest Hitler and immediately take him to court but a legal indictment proved too difficult to realize. Therefore, a command of armed officers was formed in 1938 which was to provoke an incident in the Reichstag during which Hitler would be shot. At the same, the army would commit a coup using the threat of war caused by Hitler’s aggressive policy as an official excuse.

September 15th, 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arrived in Berchtesgaden in order to discuss the growing Czech crisis with Hitler. Everything had been made ready for a coup. Chamberlain would reject Hitler’s ridiculous demands, Hitler would not be satisfied and according to the conspirators, the threat of war would be more than sufficient to intervene. Chamberlain let it be known however, he wished to discuss this first with French President Edouard Daladier. This robbed the conspirators of their excuse but another chance emerged. On September 30th, 1938, the Munich Conference was held. Again contrary to the expectations of the conspirators, Chamberlain and Daladier acceded to Hitler’s demands this time and in so doing, gave him a free hand in fact for an unimpeded invasion of Czechoslovakia. Most historians agree, this had been the best chance for the German resistance to commit a coup.

The German military successes in the field and the stranglehold by the SS and Gestapo at home caused so much support among the population that it became extremely difficult for a coup to succeed. Yet, the plotters did not remain idle. Halder devised a plan to arrest the better part of the Nazi top and – very probably – eliminate them. Things went wrong almost immediately however: on November 8th, 1939 a bomb was placed in the Bier Halle in Munich (Assault 08-11-1939) which had nothing to do with the conspiracy. Consequently all explosives and material the plotters needed were being guarded more severely.

As it was, during the first phase of the war, the military made various efforts at neutralizing Hitler but without success. Attempts were made to win some field marshals over to the resistance, including Günther von Kluge and Erich von Manstein but they refused. "Field marshals do not revolt" Von Manstein said. Civilians were not idle either. The lawyer Helmuth James Graf von Moltke founded a resistance group which would become known as the Kreisauer Kreis, a name coined by the Gestapo after Von Moltke’s estate where many of the meetings took place. The group consisted mainly of high ranking lawyers, politicians and diplomats, supported by many sympathizers. They maintained various contacts with the military resistance group. This resulted in many members of this group being arrested and executed following the failed coup of July 20th, although the involvement of the Kreisauer Kreis was minor in comparison.

As late as March 13th, 1943, a serious and well organized attempt was made to neutralize Hitler. Generalmajor Henning von Treschkov, Chief of the General Staff of 2. Armee on the eastern front, had devised a plan to eliminate Hitler during one of his visits to Heeresgruppe Mitte’s headquarters in Smolensk. Here a group of officers would draw their guns and shoot Hitler. As early as the Night of the Long Knives, Von Treschkov had alienated himself from the Nazi ideas. He did need the support though of the commander of the army group, Von Kluge but he rejected the plot. In March, Hitler visited Smolensk again and Von Treschkov devised another plan. As Hitler was returning to his aircraft, soldiers along the route would open fire on the Führer but Hitler took another route, evading the soldiers. He devised a third plan with his adjutant Fabian von Schlabrendorff. The latter would put two bombs aboard Hitler’s aircraft, disguised as bottles of liquor, allegedly a gift for a friend in Rastenburg. The freezing cold prevented the bombs from exploding though.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kreisauer Kreis

- Was a group of about twenty-five German dissidents led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who met at his estate in the rural town of Kreisau, Silesia.The circle was composed of men and a few women from a variety of backgrounds, including those of noble descent, devout Protestants and Catholics.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Night of the Long Knives

- Night of 30 June to 1 July 1933 during which Hitler killed many of the demanding leaders of the SA, including Ernst Röhm.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

The Rubicon has been crossed

The prominent members of the Kreisauer Kreis had taken a judicial education and they doubted whether a political assassination attempt, even on Adolf Hitler and his associates, would be legal. As pursuers of judicial solutions they shied away from playing judges themselves and the application of violence. But if violence was rejected, what was the alternative? Some members of the resistance considered arresting and trying Hitler but the circumstances being as they were, this was not feasible. Moreover, Hitler could count on the loyalty of his numerous fanatic followers. But if violence was opted for, it would not be easy to murder Hitler and the entire top of the party. The SS and other state agencies would continue to exist and many German soldiers were brainwashed by National socialism. So, a coup entailed the risk of civil war. This could erupt in the form of a conflict between the SS and the Wehrmacht or a mutiny within the Wehrmacht. In a successful coup, the SS had to be neutralized in some way or other as well.

Another possibility was to negotiate with the Allies and men like Goerdeler had already spent much energy there. However, as Germany’s military situation became increasingly precarious, the western Allies accepted unconditional surrender and nothing else. Moreover, agreements had been reached with Joseph V. Stalin that could not be revoked just like that.

Plagued by these questions, the conspirators felt paralyzed. An important development unfolded in the summer of 1943, when Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg actively joined the resistance. Oberleutnant Von Stauffenberg had just been discharged from hospital where he had been recuperating from the severe injuries he had sustained at the front in North-Africa. Since 1941 he was befriended with men like Von Treschkov and during Fall Weiss and Operation Barbarossa he had witnessed the mass murders of Poles, Jews, Russians and other "inferior" peoples. He loathed the senseless murders and the senseless squandering of soldiers’ lives at the eastern front and had the feeling, so he told his wife, he had to "do something in order to save the Reich." To a friend he said: "I could not look the wives and children of the fallen soldiers straight in the eyes if I were to do nothing to put an end to this senseless slaughter." With his uncle, Nikolaus Graf von Üxküll-Gyllenband he talked about his growing awareness that his rescue had not been a coincidence – that despite his mutilations he had been spared to fullfil a certain task in life. He said about the doubt of the plotters: "Freedom can only be achieved with forceful action."

36 years old, of strong will power and charismatic, Von Stauffenberg managed to inspire and stimulate the conspirators and turn the resistance into a dynamic and active movement again. The unsolvable arguments were replaced by a mutual course and a goal oriented approach. Concrete plans were drafted to take over power in the country. This was not easy because of the complex network of overlapping agencies, each with their own, often vague hierarchy. Coincidentally, a blueprint for the transition of power already existed, drafted by Hitler himself, ironically enough, with the code name Operation Walküre. This operation was meant for internal emergencies such as an uprising among the foreign slave laborers. The Ersatzheer (reserve army), comprising some 4 million men, was to be mobilized and deployed in cases like that. These troops had orders to occupy the cities, declare a state of emergency and impose military law on the population. Only the army was to carry out this operation; the Nazi party and the SS had no knowledge of it whatsoever. In order to secure the cooperation of men, loyal to the Nazis, a attempt at a coup by the SS was used as a justification for this operation. High ranking SS and party officials were to be arrested. Only later it would become clear that the army had committede a coup.

The possible deployment of the Ersatzheer was a stroke of good fortune as most prominent conspirators were serving in it. General der Infanterie, Friedrich Olbricht, a friend of Von Treschkov was Chief of the Allgemeines Heeresamt (general office of the armed forces), part of the Ersatzheer. He offered Von Stauffenberg, just discharged from hospital, the job of his Chief of Staff, something Von Stauffenberg willingly accepted. Supreme commander of the Ersatzheer was Generaloberst Friedrich Fromm. Because of his extremely important position, Fromm had been approached by the conspirators. He tolerated the preparations for Operation Walküre but refused to participate actively. It was clear he would only lend his support if the success of the coup was crystal clear. Another man, closely involved was Oberst Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim, a former class mate of Von Stauffenberg at the Kriegsakademie.

For the period following the coup, a provisional government was formed and a scenario drafted for the future politics to be pursued. 64-year old Beck would become the new head of state. 59-year old Goerdeler would become Reichskanzler with 52-year old Julius Leber his vice-chancellor. Wilhelm Leuschner would become Reichspräsident and Ulrich Wilhelm Graf Schwerin von Schwanenfeld state secretary. Secretaries of Foreign Affairs, Justice, Finance and War would be Ulrich von Hassell, Dr. Josef Wirmer, Dr. Johannes Popitz and Friedrich Olbricht respectively. Von Witzleben would become the new supreme commander of the armed forces, Von Treschkov would become Chief of Police and Von Stauffenberg willingly accepted the function of State Secretary of War.

Von Stauffenberg saw no good in legal or non-violent methods to neutralize Hitler. In his opinion, there was only one solution, although this went straight against his principles, his code of honor, his military oath and his moral values: to kill Hitler by means of an attempt. To Von Stauffenberg, who considered himself, based on his noble descent and his attitude, a loyal German, a good Catholic, an officer and an aristocrat, this was a painful conclusion. As he said himself, he would be betraying his own conscience if he were to take no action.

The next problem was predicting Hitler’s movements. It was easy to ascertain where Hitler was at any given moment but his plans were difficult to predict. Hitler never stuck to a strict schedule, he wore protective clothing and he was always accompanied by an armed guard. Even his car and his private plane had additional armor plating and protection. Moreover, Hitler hardly appeared in public any more and stayed in Berlin or in his country residence in Berchtesgaden only rarely. Unless they could catch him on one of his rare trips to the outside world, the conspirators had to assassinate Hitler in his headquarters. That was located in Berchtesgaden and from July 14th, 1944 onwards in the Wolfsschanze (Wolves’ lair) in the woods near Rastenburg in eastern Prussia. This military headquarters was surrounded by moors and the Mazurian lakes in what is now northeastern Poland. It was not easy to make an attempt at murder in one of these locations and so, somebody had to be found who could closely approach Hitler.

Von Stauffenberg declared himself willing to take the attempt upon himself although, in his position as Oberstleutnant and his job as Chief of Staff of the Allgemeines Heeresamt, he was no more suitable than most other officers. His co-plotters protested as Von Stauffenberg was severely disabled by the loss of an eye, a hand and two fingers of the other. Moreover, he was the acknowledged leader of the conspiracy, the instigator and he would be in charge of the coup as Von Treschkov was unable to leave the eastern front.

On April 1st, Von Stauffenberg was promoted to Oberst and on June 20th, he was given the high position of Chief of the General Staff of the Ersatzheer. Von Stauffenberg’s direct superior was now Fromm and Von Stauffenberg’s former position as Olbricht’s Chief of Staff was now taken by Merz von Quirnheim. These events shed an entirely new light on the matter: in this function, Von Stauffenberg would be frequently sent for by Hitler. In Von Stauffenberg’s view, fate had given them this opportunity and they had to take it. Time was running out. Shortly before, the Allies had landed in Normany and among the conspirators, Von Stauffenberg had the easiest access to Hitler, hence it had become clear that he was to make the attempt. Fact was also that Julius Leber, vice-chancellor-to-be after the coup, had been arrested on July 5th, shortly after a meeting with other plotters. Von Stauffenberg’s colleagues agreed with aversion but there was no alternative. After the attempt, Von Stauffenberg should return to Berlin as soon as possible to take charge of the coup. He declared: "It no longer concerns the Führer, the country nor my wife and three children but the entire German population." Nobody made any illusions; the chance of success was very slim. All conspirators did agree however that the attempt had to be made whatever the cost. If the attempt should fail, an effort had to be made to commit a coup anyway. Although they all were skeptical, they remained confident the plan would succeed.

On July 3rd, Von Stauffenberg met Generalmajor Hellmuth Stief, Chief of the Organisationsabteilung des Generalstabes des Heeres and co-conspirator in Berchtesgaden. He received two bombs from him for the attempt. Based on his position, Stieff also had easy access to the Führer and had already offered to make an attempt but now he refused. After the long period of waiting and disillusions, it appeared he had somehow lost his courage.

On July 11th, an opportunity presented itself. Von Stauffenberg was called to Berchtesgaden in order to report on the situation of the Ersatzheer. Von Stauffenberg traveled to Berchtesgaden with a bomb. Everything was prepared: a car and a plane were standing by to take him back to Berlin as fast as possible. The plotters had agreed however that not only Adolf Hitler but Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and – if possible – Hermann Göring be eliminated as well. As it was, Himmler was absent and Von Stauffenberg returned to Berlin with the bomb. On July 14th, Hitler moved his headquarters from Berchtesgaden to Rastenburg.

On July 15th, they got a second chance and Von Stauffenberg flew to the Wolfsschanze near Rastenburg. Himmler was absent again, a fact Von Stauffenberg passed on to Berlin in a coded message. Beck and Wagner urged to postpone the attempt again but Olbricht and Merz von Quirnheim convinced Von Stauffenberg to kill only Hitler (all this without Fromm being informed). When Von Stauffenberg returned to the room and Hitler he found that Stieff had already removed his briefcase as a precaution. Von Stauffenberg immediately called Olbricht in Berlin, who had already issued the first order for Operation Walküre. Merz von Quirnheim barely succeeded in countermanding the order on the pretence it had been an exercise.

The Gestapo accepted the story but things could not go on like this. On July 20th, Von Stauffenberg had to come to the Wolfsschanze again and the plotters agreed on Von Stauffenberg carrying out the attempt, regardless of Himmler being present. On July 18th, Von Stauffenberg heard about a rumor, circulating in Berlin, to the effect that the Führerhauptquartier could be blown any moment. "Then we have no more choices," he responded. "The Rubicon has been crossed."

In the early evening of July 19th, Von Stauffenberg halted near a small church in Berlin-Dahlem, a suburb of Berlin, where a service was going on. He stood in the back, alone, for a long time and afterwards let himself be driven home. He had a lengthy conversation with Adam von Trott zu Stolz, member of the civilian resistance. He spent the rest of the evening with his brother Berthold who was also involved in the plot.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kreisauer Kreis

- Was a group of about twenty-five German dissidents led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who met at his estate in the rural town of Kreisau, Silesia.The circle was composed of men and a few women from a variety of backgrounds, including those of noble descent, devout Protestants and Catholics.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- mutiny

- Revolt of soldiers or sailors against the authorities.

- National socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

July 20th, 1944: on the way to Rastenburg

Around 05:00 hours in the morning of July 20th, Von Stauffenberg awoke in a room of a house on the Wannsee, temporarily lent to him by a relative. Using only his three fingers he shaved and dressed. At 06:00 his young adjutant, Oberleutnant Werner von Haeften arrived in a staff car. Von Stauffenberg got into the car with his briefcase. He was not afraid but calm and cheerful. They drove to the airfield where Stieff was waiting for them. The three officers took off at 07:00 for Rastenburg on a slow Heinkel He 111. This aircraft had been made available to them by General der Artillerie Eduard Wagner, Oberquartiermeister des Heeres and a fellow conspirator. They arrived in Rastenburg airfield around 10:15 and the pilot was ordered to have the plane ready for take off at 12:00 hours. The trip from the airfield to the Wolfsschanze was about 3.7 miles.

In order to get to headquarters, they had to pass three checkpoints, guarded by SS men. The buildings stood in the shadow of tall pine trees and the area was surrounded by mine fields and barbed wire, some of them electrified. The special passes of the three officers were checked at the checkpoints. This proceeded smoothly but after the attempt they had to act fast and cold-blooded to be able to leave the area.

The meeting was to begin at 13:00 hours and Von Stauffenberg still had time on his hands. After he had had breakfast with Von Haeften, he briefly spoke to General der Nachrichtentruppen Erich Fellgiebel. This general was also involved in the plot and had to inform Olbricht if and when the attempt had succeeded and subsequently was to cut all communication between the Wolfsschanze and the outside world. Of all the men in Rastenburg, only Von Stauffenberg, Von Haeften, Fellgiebel and Stieff knew what was coming. At 11:00 hours, Von Stauffenberg had a talk with two generals, followed at 11:30 by a meeting with Generalfeldmarschal Wilhelm Keitel, Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht which lasted 45 minutes. He was already waiting for him as Hitler had decided to forward the meeting for half an hour, to 12:30. He did so because Benito Mussolini, the ousted Italian dictator, was to arrive that afternoon. Von Stauffenberg was worried for a moment but soon reached the conclusion that the attempt would take place a mere half hour sooner.

At the War Department on the Bendlerstrasse in Berlin, Olbricht was dealing with routine matters. He expected a phone call from Fellgiebel at 13:30 at the latest. Then he would send for Beck immediately, who was at his home in a Berlin suburb, in order to kick off Walküre. They would do so together with discharged Generaloberst Erich Hoepner who was to arrive at the end of the morning. As soon as the troops of the Ersatzheer had arrived, the War Department was to be occupied, as well as the radio stations and other important centers. Numerous commanders in the Reich and in the occupied areas had been asked for help who subsequently would have to be informed in order to immobilize the SS. SS-Obergruppenführer Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf, chief of the Berlin police, as well as Generalleutnant Paul von Hase, military commander of Berlin, would lend their support by keeping a force of their own men in reserve.

In Paris, the only general directly involved in the plot was the military commander of France, General der Infanterie Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel. He was surrounded by a number of young officers who gladly wanted to be involved in the conspiracy, including his adjutant, Oberstleutnant Cäsar von Hofacker, a nephew of Von Stauffenberg. Von Stülpnagel knew that his commander Von Kluge, just like Fromm, was willing to render assistance if and when the success of the coup was crystal clear and the others had done the dirty work but Von Kluge’s HQ was at some distance from Paris. Von Stülpnagel had his HQ in Hotel Majestic on the Avenue Kléber. Here he waited for a phone call from Berlin, authorizing him to deal with the SS and the Gestapo.

Towards 12:30 hours, Hoepner arrived at the War Department. He was to become Commander-in-Chief of the Ersatzheer in case Fromm refused to cooperate. He had lunch together with Olbricht and afterwards they retuned to their office. They could do nothing but wait for Fellgiebel’s phone call.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

The bomb in the chartroom

In the 15 minutes Von Stauffenberg was free before the meeting began, he asked where he could refresh himself and put on a clean shirt, covered as he was in sweat because of the warm and humid weather. An officer showed him to the bathroom. On his way, Von Stauffenberg encountered his adjutant Von Haeften, carrying the briefcase containing the two bombs. Once inside, Von Stauffenberg put on a clean shirt and subsequently he activated one of the bombs with a special pair of tongs, breaking an ampoule containing an acid. The acid would eat through a wire and release some kind of hammer that would hit the detonator. It would take about ten minutes before the bomb would explode but this was a rough estimate and the speed with which the acid ate through the wire depended on various factors. When Von Stauffenberg went to work on the second bomb, he was disturbed by an Oberfeldwebel who had come to fetch him as the meeting was to begin. Von Stauffenberg could not finish his work and Von Haeften took the second bomb with him. With one live bomb in his briefcase Von Stauffenberg went out. Within 10 minutes – or sooner – the bomb would explode.

In the corridor Von Stauffenberg met Keitel again. It was 12:30 already and Keitel was touchy and nervous. He did not like being late for the Führer. Another officer offered to carry Von Stauffenberg’s case. His refusal did not evoke any suspicion; everybody knew and accepted he did not like to be assisted.

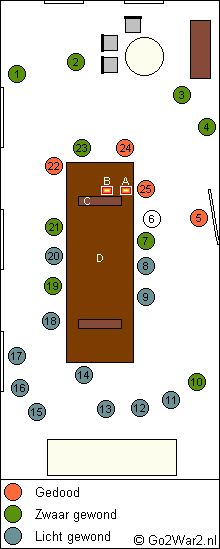

Von Stauffenberg hoped they were going to the visitors' bunker. The concrete walls of this complex would reflect the blast of the explosion mostly inwards. Since July 15th, however meetings were held in the adjacent chartroom, a wooden hut measuring some 16.4 by 39 feet with three large windows. This building was lightly re-inforced with concrete but an explosion here would be far less effective. Because of the heat, the windows were wide open. Once inside, Von Stauffenberg requested to be placed as close to the Führer as possible, probably because his hearing had been impaired by the injuries he had sustained.

The meeting had already started as the officers entered the room. Neither Himmler nor Göring was present. Generalleutnant Heusinger reported on the situation at the eastern front. Most of those present stood bent over a massive oak chart table. Keitel introduced Von Stauffenberg to Hitler. Hitler shook his hand. They had met before. Von Stauffenberg placed his briefcase on the floor and with his boot he shoved it under the table. Keitel suggested Von Stauffenberg be allowed to report on the status of the Ersatzheer as soon as Heusinger had finished. The Führer nodded approval. It was near 12:39. Von Stauffenberg only had a few minutes left before the bomb would explode. He turned to the officer next to him, said he had to make an urgent phone call to Berlin and left the room. Keitel made a meddlesome effort to catch up with him but changed his mind. Von Stauffenberg walked past the office of the telephone operator, through the corridor and out the door. Here he passed the inner checkpoint and traversed a lawn on his way to the bunker at the far end where Fellgiebel was waiting for him.

| The positions in the chart room, Thursday, July 20th, 12:37 - 12:39 | |

A: First position of the case with the bomb B: Second position of the case with the bomb C: Massive oak leg of the table D: Massive oak chart table | 1. Konteradmiral Karl-Jesko von Puttkamer, naval adjutant of Hitler 2. General der Infanterie Walther Buhle, Chief General Staff Heer in OKW 3. Oberstleutnant i. G. Heinz Waizenegger, adjutant of Keitel 4. General der Flieger Karl-Heinrich Bodenschatz, liaisonofficer supreme command of the Luftwaffe to Hitler 5. General der Flieger Günther Korten, Chief General Staff Luftwaffe 6. Oberst i. G. Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, Chief Generale Staf Ersatzheer 7. Generalleutnant Adolf Heusinger, deputy Chief General Staff Heer 8. Adolf Hitler 9. Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel, supreme commander Wehrmacht 10. Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, Chief General Staff Wehrmacht 11. General der Artillerie Walter Warlimont, deputy Chief General Staff Wehrmacht 12. Ministerialrat Franz Edler von Sonnleithner, representative Foreign Affairs to Hitler 13. Major i. G. Herbert Büchs, adjutant Jodl 14. Heinz Buchholz, stenographer 15. SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, representative Waffen-SS to Hitler 16. Oberst i. G. Nikolaus von Below, Luftwaffe-adjutant Hitler 17. SS-Hauptsturmführer Otto Günsche, adjutant Hitler 18. Konteradmiral Ing. Hans-Erich Voss, representative supreme command Kriegsmarine to Hitler 19. Generalmajor Walter Scherff, writer war diary 20. Major Ernst John von Freyend, adjutant Keitel 21. Kapitän zur See Heinz Assmann, Admirality officer in OKW 22. Heinrich Berger, stenographer 23. Oberstleutnant i. G. Heinrich Borgmann, adjutant Hitler 24. Generalleutnant Rudolf Schmundt, chef-adjutant Wehrmacht to Hitler 25. Oberst i. G. Heinz Brandt, deputy of Heusinger |

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Heer

- German army or land forces. Part of Wehrmacht together with “Kriegsmarine” and “Luftwaffe”.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Return to Berlin

At 12:42 an ear shattering explosion was heard. Von Stauffenberg and Fellgiebel pretended to be frightened and saw smoke bellowing from the chartroom. Von Haeften halted near the bunker in a loaned car. Von Stauffenberg got in and the two left immediately. They had to get out of Rastenburg before the area was completely sealed off. The car drove at 55 yards past the chartrooom. Security people ran around haphazardly. Persons were being carried out but from that distance it could not be seen whether they were dead or injured. The chartroom itself seemed to be utterly destroyed and so Von Stauffenberg was convinced that nobody could have survived the explosion.

Von Stauffenberg was able to pass the first and second checkpoint easily. At the third, the car was stopped however by an Oberfeldwebel. General alarm had been sounded and no one was allowed to leave the area. Von Stauffenberg got out, grabbed the telephone in the guardhouse and called the adjutant of the Rastenburg commander. Incidentally, this Rittmeister knew Von Stauffenberg from their lunch earlier that day. He gave Von Stauffenberg permission to pass. The Oberfeldwebel wanted to hear the order himself and then raised the barrier. The car drove to the airfield at high speed. On the way, Von Haeften disassembled the second, unused bomb and threw the parts out of the car. Around 13:15 hours, the Heinkel with Von Stauffenberg and Von Haeften aboard, took off for Berlin. Von Stauffenberg had no official confirmation of Hitler’s death but he did not doubt a second. The Führer could never have survived the blast. The coup had begun.

Von Stauffenberg could not know that an officer in the chartroom, Oberst i.G. Heinz Brandt, ironically enough a sympathizer of the resistance, had stubbed himself on the briefcase. He had shoved it further under the table behind one of the legs. This massive, vertical board, together with the massive, 4 inch thick tabletop, had shielded Hitler from the explosion for the most part. The Oberst, two generals and a stenographer would succumb to their injuries. Nine others were taken to hospital and the rest was only slightly injured. Hitler’s hair had been scorched, his right arm was temporarily paralyzed, his right leg was badly burnt, his eardrums were ruptured and he was in complete shock. The vibrations he suffered, a symptom of his neurologic disorder (Parkinson) grew even worse. Moreover he had some superficial burns and his trousers were torn. His first reaction was anger as his new trousers were torn. His second reaction was to order the SD to cut all communication with the outside world: nobody was to know what had happened.

Shortly after Von Stauffenberg had left, Fellgiebel walked towards the chartroom. He stood thunderstruck when he saw Hitler emerge, supported by Keitel. Fellgiebel knew Von Stauffenberg was convinced of Hitler’s death and called Berlin urgently to report the attempt had failed. He said: "Something terrible has happened: the Führer is alive!" This vague message brought no clarity in Berlin. After his phone call, Fellgiebel discovered the entire communication network was already under control of the SS. Stieff, who was with him, was of the opinion that a coup was no longer an option now and that the conspirators better had to try and save their own skins.

Meanwhile, Hitler had sent for Himmler and charged him with the investigation. His headquarters were nearby and so Himmler was at Hitler’s side quickly. It soon became clear that the bomb had not been dropped by an aircraft, as was briefly assumed, but that Von Stauffenberg was behind it, who had left in a hurry. Meanwhile, Hitler had the visit by Mussolini continue as planned.

In the course of the morning, the lawyer Hans Bernd Gisevius, a fellow conspirator, went to Von Helldorf’s office. They could not stand the insecurity any longer and called SS-Brigadeführer Arthur Nebe, a sympathizer of the resistance. He had found out an explosion had occurred in the Wolfsschanze and that Himmler had started an investigation. He agreed to meet Gisevius somewhere in order to talk undisturbed. They erred however about the meeting place so they sat waiting for each other on different locations.

At the War Department, the afternoon proceeded without any message from the Wolfsschanze. Von Stauffenberg was to arrive late in the afternoon and there had still not been a phone call from Fellgiebel. The only person in Berlin who knew of the explosion was Joseph Goebbels. He was the sole high ranking Nazi in Berlin and he heard about the explosion around 13:00 hours but no more than that.

As late as 15:30 hours, the lines of communication were temporarily restored. Generalleutnant Fritz Thiele, chief of Olbricht’s communication department, heard a vague story from Rastenburg to the effect that an attempt had been made on Hitler. There was no mention of Hitler being dead or alive. Thiele went to see Olbricht in a hurry. The latter faced a difficult decision. Von Stauffenberg was not expected to be back before 16:45 at Rangsdorff airfield. He could provide certainty but it would be disastrous for the coup if Walküre be postponed that long. The forces supporting Hitler could not be given the opportunity to take counter measures. Due to the absence of Von Stauffenberg and Von Treschkov, Olbricht had only Hoepner to advise him but he was indecisive and nervous. Towards 15:45 Olbricht reached the conclusion he had to make a decision. Without consulting Fromm, he decided to issue the orders for Operation Walküre. Five minutes later, the orders were transmitted to all units of the Ersatzheer.

Around 16:00 hours, Von Stauffenberg and Von Haeften arrived at Rangsdorff airfield, much earlier than expected as the meeting had taken place earlier. There was no car standing by, as had been agreed before and he made a worried phone call to the department. He was told the orders for Operation Walküre had just been issued and he shouted: "but Hitler is dead!" He drove to the Bendlerstrasse as fast as possible In a commandeered car.

After having heard Von Stauffenberg’s voice, Olbricht took the courage to simply confront Fromm with the situation as it was. Olbricht asked Fromm for permission to issue the orders for Operation Walküre to all units of the Ersatzheer although that had already been done without Fromm’s knowledge. Fromm however wanted confirmation by Keitel of Hitler’s death first. Keitel was called and he stated an attempt had been made but it had failed. Fromm told Olbricht brusquely there was no reason anymore to issue the orders for Walküre. Olbricht did not understand at all and assumed Keitel had been lying. The coup had to continue anyway. Von Witzleben and Beck, who could arrive at any moment, were to deal with Fromm.

Soon Beck entered, closely followed by Von Stauffenberg and Von Haeften. Von Witzleben had not arrived yet. Other officers came in too, including Gisevius and Von Helldorff. Von Stauffenberg displayed great energy and was eager to get to work. He called his nephew Von Hofacker in Paris who informed Von Stülpnagel that Hitler was dead so he could take steps against the SS and the Gestapo.

After having heard Hitler’s statement, Beck doubted if Hitler was dead but Von Stauffenberg said: "It was like a 15cm shell had struck. It is impossible anyone could have come out alive," He could not explain the fact that Keitel was still alive but the conspirators were going to act on the presumption that Hitler was dead. A lot of things still had to be done. Gisevius considered it wrong the radio stations had not yet been occupied and that Fromm should be shot if he did not support them. Von Stauffenberg did not want any of this and at 17:00 hours, the conspirators went to see Fromm. He was furious when he heard the orders for Walküre had already been issued. When he heard that Von Stauffenberg had placed the bomb, he said Von Stauffenberg could do best to commit suicide. When Von Stauffenberg refused, Fromm had all conspirators arrested. Subsequently, Olbricht said they were in power now, not Fromm. "We’ll arrest you now," he said. Fromm resisted but was locked up in an office. The supreme command of the Ersatzheer was subsequently transferred to Hoepner.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

The end of the coup

In Rastenburg, various high ranking Nazis had come to pledge their support to Hitler: Heinrich Himmler, Hermann Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Karl Dönitz and others, except Joseph Goebbels who stayed in Berlin. At 16:00 hours, Benito Mussolini arrived at the Wolfsschanze. He solemnly told Hitler: "Heaven has stretched its protective hand over you,". At 17:00, the company went to have tea.

Meanwhile, Himmler had ordered to arrest Von Stauffenberg at Rangsdorff airfield. He assumed the attempt had been made by a single, insane officer. SS-Oberführer Piffräder – charged with Von Stauffenberg’s arrest - passed the latter’s car on its way to the Bendlerstrasse. It had also become clear that orders for Walküre had been issued, making it obvious the attempt had not been the work of one man. As Fromm, in his capacity of supreme commander of the Ersatzheer, was apparently deeply involved in the coup, Hitler appointed Himmler the new commander of the Ersatzheer. He left for Berlin by plane.

The tea break turned into an crazy scene. Hitler’s guests competed with each other giving him credit, cursing the conspirators and blaming them for this stab in the back. In a hysterical reaction, without bothering about Mussolini, they started blaming each other bitterly. It even went so far that Göring got into an argument with Von Ribbentrop about the right to have ‘von’ in his name. Then Hitler rose. Furious, he shouted: " I will crush and destroy these criminals who have dared to stand up against me and Providence." Mussolini was the only one who retained his dignity. He rose and said goodbye.

Around 17:30, phone calls started coming in at the War Department from all corners of the Reich and the occupied areas. Beck, Olbricht and Von Stauffenberg could hardly handle them all. Beck talked to Von Stülpnagel who assured him the conspirators could count on his support. Piffräder and two SS men also arrived at the War Department. It had not taken him any trouble to enter. He said he wanted to talk to Von Stauffenberg. Von Stauffenberg, accompanied by a few officers had the swearing Piffräder arrested.

Meanwhile, Gisevius grew increasingly worried as the units had not arrived yet that were to seal off the government quarter. The radio stations had not yet been occupied and the high ranking Nazis in Berlin not yet arrested or murdered either. Towards 18:00 hours the Walküre units arrived at the Bendlerstrasse. Apart from other units from various schools, these also included the Wachbattalion Gross Deutschland commanded by Major Otto-Ernst Remer. Remer’s superior was Paul von Hase, the military commander of Berlin and fellow conspirator but Remer was a fanatic Nazi. There was an abundance of troops but no one was ordered to occupy the radio stations. The entire occupation of Berlin was sloppily and poorly coordinated. Von Helldorf’s police units did nothing at all as the conspirators wanted the coup to be a military affair. Von Stauffenberg and Olbricht were far too busy to deal with it all and presumed that their plans were being carried out.

Due to the bad coordination, Remer was ordered to arrest Goebbels. Towards 17:00 hours, Hitler had called Goebbels telling him that in Berlin a coup was brewing. He also ordered him to draft a radio bulletin in order to kill all rumors that Hitler was dead. Goebbels did so together with Albert Speer who told him troops were assembling on the street in front of his house. Meanwhile, Oberleutnant Hans Hagen came in, who had delivered a lecture to Remer’s troops that afternoon. He suggested to Goebbels to see Remer immediately as he was still loyal. Goebbels agreed and Hagen left to look for Remer. Von Hase meanwhile had countermanded Remer’s order to arrest Goebbels as on second thoughts, he did not trust him anymore. But Hagen had found Remer and convinced him to ignore Von Hase’s orders and to go talk to Goebbels.

At 18:45, the message drafted by Goebbels and Speer, that Hitler was still alive, finally went on air and it could be heard all over Europe. At the moment Von Kluge, who did not yet support the coup, was convinced over the phone by Beck to support the coup, he read a copy of the radio bulletin. Beck acknowledged the situation in Rastenburg was unclear. Von Kluge, not wanting to take any chances, said he would discuss the matter first with his officers. Beck knew Von Kluge well enough to realize he was lost to the resistance.

At the Bendlerstrasse, the conspirators had also heard the bulletin. Their unease increased and they sent the following denial to all agencies they were in contact with: "The message just transmitted by radio is incorrect. The Führer is dead. The measures that have been ordered are to be carried out as soon as possible." The phones at the Bendlerstrasse were ringing steadily now and kept Beck, Olbricht and Von Stauffenberg continuously busy. The conspirators had too much to explain. It was obvious that whatever had happened to the Führer, the Nazis still held a tight grip on the situation. Only in Paris, everything proceeded smoothly.

At 19:30, Von Witzleben finally arrived at the War Department. He was in a very bad mood. Everybody rose but Von Witzleben talked only to Beck who was the only one outranking him, being the new head of state. "A big mess, all this," Von Witzleben fumed. The security units began to disappear from the streets as it became clear that Hitler was still alive and various officers at the War Department, led by Oberleutnant Franz Herber and a certain Von der Heyte wanted to take counter measures.

Meanwhile, Remer had arrived at Goebbels’ house. He was asked if he was absolutely loyal to the Führer and Remer confirmed without hesitation. Subsequently, Goebbels called Hitler and had Remer talk to him. Hitler placed Remer under his personal command and promoted him to Oberst on the spot. Awaiting Himmler’s arrival, the safety in Berlin was now in Remer’s hands. He left in a hurry in order to rally his men for an attack.

In the meantime, Von Kluge was worried about what he had gotten into. The dangerous phone calls to the conspirators disturbed him. Von Stülpnagel however was under way to Von Kluge with Von Hofacker and others to persuade him to authorize the measures taken in Paris without his consent. Von Hofacker told him about the importance of the action in France and Von Kluge’s power. "Gentlemen," Von Kluge said, "the matter has gone wrong." Von Stülpnagel now also understood Von Kluge was lost to the cause of the resistance. Only then was Von Kluge confronted with the fact that Von Stülpnagel had had SS and Gestapo officers arrested on his own accord. Von Kluge trembled with rage and ordered the men to be released. After his rage had died down, he suspended Von Stülpnagel and advised him to disappear.

Himmler arrived in Berlin after midnight. He did not show up in the Bendlerstrasse, although that was his new headquarters now, but preferred to direct events from Goebbels’ house.

Meanwhile at the Bendlerstrasse, despair prevailed. On radio it was announced that Hitler would address the nation later that evening. It had also become obvious in the meantime that the security troops had left and that they would have to defend themselves. The officers at the War Department who wanted to take counter action had managed to smuggle arms inside and decided to release Fromm.

At 22:50 Herber, Von der Heyte and their followers launched their attack on the offices of the conspirators. They went to Olbricht first, accused him of events happening aimed against the Führer and wished to see Fromm. A secretary witnessed this and went to see Von Stauffenberg. He and Von Haeften went to Olbricht to help him but were received with a hail of bullets and turned around fast. Von Stauffenberg had been hit in his left arm and was bleeding profusely. A short fierce fire fight ensued between the officers remaining loyal to the conspirators and those loyal to the Hitler.

Very soon, Beck, Hoepner, Olbricht, Von Stauffenberg, Merz von Quirhheim and Von Haeften were arrested. After Fromm had been liberated around 23:00 hours, he held a short court martial. He had to prove he had nothing to do with the conspiracy. The five officers were sentenced to death and Hoepner was arrested. Beck wanted to commit suicide and was given a gun by Fromm. His first attempt failed as the first bullet only grazed his temple. Herbert’s men wanted to pull the gun out from his hands but the injured Beck begged to have another try and Fromm approved.

Fromm told the others should they want to write something to their wives, they should do so. Olbricht and Hoepner sat down to write. Von Stauffenberg, seriously injured lay back in a chair and was tended to by Von Haeften. Meanwhile, Fromm deployed a ten men firing squad in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock, using Remer’s men. When Fromm returned, Beck made his second attempt at suicide which failed once more. Beck was put out of his misery with a shot in the neck by a Feldwebel. The others were rushed down the stairs to the courtyard. Von Stauffenberg was barely conscious and was supported by Von Haeften.

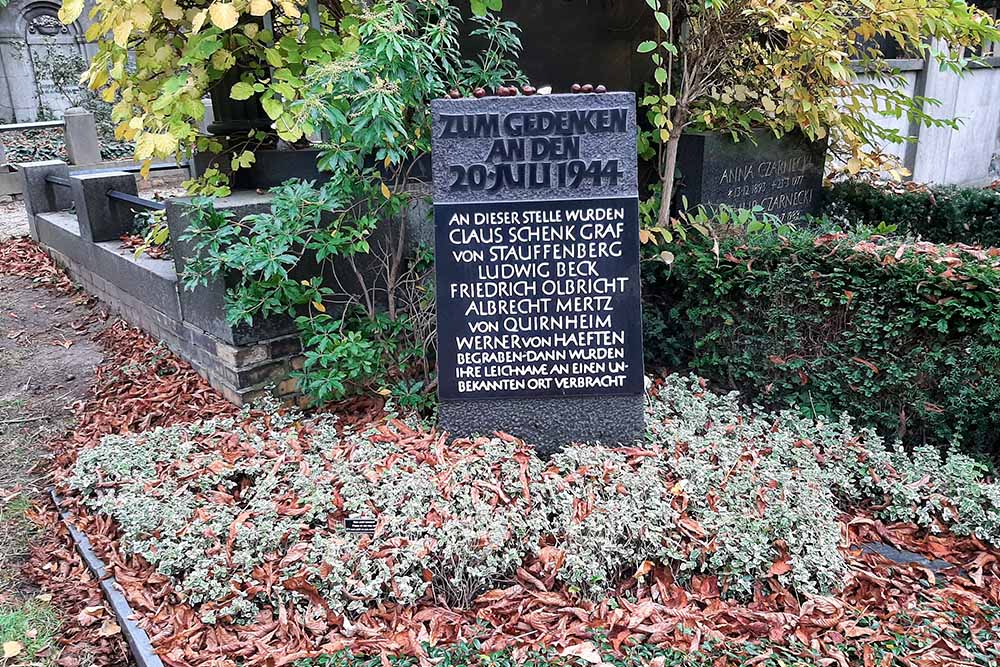

At 00:15 in the morning of July 21st, Von Stauffenberg, Olbricht, Von Haeften and Merz von Quirnheim were placed in front of a heap of sand in the courtyard of the Ministry of War. Illuminated by the headlights of a car, they were to be executed by a 10-man firing squad in sequence of their rank. When the squad took aim to execute Von Stauffenberg, Von Haeften threw himself in front of him to catch the bullets. The squad took aim once more and in the split second before he was mortally hit, he shouted something at his executioners. Due to the echoing noise, his words were hard to understand. According to some, he yelled: "Es lebe unser Heiliges Deutschland" (Long live our Holy Germany). According to others – and that seems more plausible – with his last words, Von Stauffenberg’s referred to his great mentor, the poet Stefan George and the title of the latter’s poem on German resistance: "Es lebe unser geheimes Deutschland" (Long live our secret Germany). Subsequently, the bodies were buried in the old St. Mattheus cemetery in Berlin, dressed in their uniforms with all their decorations. The next day though, Himmler ordered the bodies to be exhumed and cremated. The ashes were dispersed in the fields.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

The aftermath

On July 21st, at 01:00 hours, Hitler’s voice sounded on all German radio stations, hard to hear because of the effects of the shock.

- A very small clique of ambitious, unscrupulous and at the same time treacherous and stupid officers has hatched a conspiracy in order to kill me and simultaneously eliminate the German army leadership. The bomb that has been placed by Oberst von Stauffenberg, exploded 6.5 feet from my right. A number of loyal associates sustained severe injuries. Four of them are dead. I am entirely unhurt myself, apart from some minor bruises, bumps and burns. I consider this a confirmation of the task given to me by Providence to continue my walk of life in the way I have done until now. The clique of these conspirators is very small. It has nothing to do with neither the Wehrmacht nor with, above all, the German people. It is a small band of treacherous elements that will now be ruthlessly eliminated. I therefore order at this moment that first of all, no military authority, no troop commander, no soldier shall obey any order from these criminals but on the contrary, it shall be every one’s duty to arrest anyone issuing or obeying these orders or, in case of resistance, to neutralize them immediately. (…) This time, the matter will be dealt with in the way we National socialists are used to.

In the evening of July 20th, Generalmajor Henning von Treschkov heard about the failed attempt and decided to end his life. The next morning he drove to the front line and entered no man’s land. There he pretended having been killed by Soviet bullets; he fired some shots in the air and them committed suicide with a hand grenade. Generalmajor Hellmuth Stieff and General der Nachrichtentruppen Erich Fellgiebel were arrested in the Wolfsschanze on July 20th. Stieff had soon withdrawn his support to the coup because in his view, the coup had already failed even before it had started. Generalfeldmarschal Erwin von Witzleben had not stayed in the War Department for long: towards 22:00 he was back at home. "Tomorrow," he said bitterly, "the executioners will be here." He was arrested the next day, just like Generaloberst Erich Hoepner. Hans Bernd Gisevius managed to escape to Switzerland with forged papers. He survived the war and testified at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. General der Artillerie Eduard Wagner did not await Hitler’s revenge. He committed suicide three days after the attempt. Generalfeldmarschal Günther von Kluge was relieved of his function on August 17th. He knew what was in store for him and on his way to Germany he committed suicide near Metz by taking cyanide.

Hitler ordered that no mercy should be shown. The chief of the SD, Ernst Kaltenbrunner was charged with collecting evidence. He was assisted by a large group of investigators, allegedly over 400 at one given moment. Nearly 5,000 persons were arrested and hundreds of them were executed. Hitler was aghast over the scope of the resistance against his regime. He wanted the merciless interrogations to be followed by a series of show trials as soon as possible. The prisoners were often tortured and were shackled hand and feet while in their cells. They were starved and robbed of their sleep as the light in their cells was always left on.

The trials took place illuminated by spotlights and were recorded on film in their entirety, as well as the executions. The Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) chaired by Dr. Roland Freisler was in session for six long months to sentence the defendants. Freisler wanted to turn these trials into the pinnacle of his career. He used name calling and sarcasm as his main weapons, He could suddenly start yelling and screaming with the cold fury of a sadistic school teacher. Most of the conspirators, who had been given suits that were too large and without belts, passively underwent their trial. They answered as little as possible so as to give Freisler no chance for a verbal attack. In particular Von Witzleben and Hoepner were profoundly ridiculed and offered Freisler ample chances for sarcasm.

The intellectuals, including many lawyers, fared best of all in general. Von Moltke in particular was a worthy opponent of Freisler. He held a nearly intellectual debate and took great satisfaction from his duel with Freisler. Others, like Goerdeler managed to raise the curiosity of their interrogators in such a way that they were allowed to live. Goerdeler drafted lengthy and intricate statements to prolong the interrogations and wrote endless letters. He hoped to win time until the end of the war so he would be liberated but eventually, the interrogators saw through his game. He was executed shortly after Leber and Von Moltke.

Hans von Dohnanyi as well tried to win time by making his wife agree to bring drugs into his cell, contaminated with diphtheria. By making himself chronically ill, he hoped to evade sentencing but in the end, he was also hung, partially paralyzed.

Admiral Wilhelm Canaris also managed to prolong the interrogations. He managed to confuse his interrogators frequently with an avalanche of seemingly important information that hurt no one but did require extensive research. This did not do him any good either: he and his deputy in the Abwehr, Generalmajor Hans Oster were hung in Flossenbürg concentration camp, along with Hans Dohnanyi and reverend Dietrich Bonnhoeffer.

The major conspirators were hung from meat hooks by piano wire. "Like cattle in a slaughterhouse" as Freisler had ordered. On Hitler’s orders, the executions were recorded on film. The executioners drank brandy, swapped jokes and laughed as Hitler’s enemies died a slow and terrible death by suffocation.

General der Infanterie Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel was asked to come to Berlin to account for himself. On his way to Germany he also attempted to commit suicide but was "only" gravely inured. His body was found floating in a river and he was taken to a field hospital in Verdun. He was operated upon and later on arrested in hospital and hung.

Generalfeldmarschal Erwin Rommel had always opposed a coup but he had known of it. Shortly before the attempt he was gravely injured when his staff car was attacked by aircraft near Livarot in France on July 17th. Being an accomplice but due to his great popularity, he was given the choice to stand trial as a traitor or commit suicide and so prevent his family from Sippenhaft. Sippenhaft meant that next of kin of a criminal would also be persecuted. Rommel took the second option and committed suicide on October 14th. The population was made to believe Rommel had succumbed to his injuries. He was given a state funeral.

Von Treschkov’s adjutant, Oberleutnant Fabian von Schlabrendorff probably suffered the worst treatment of all prisoners. After his arrest by the Gestapo, he was interrogated. Von Schlabrendorff, an experienced lawyer, found out his interrogator was using forged documents. Therefore, he denied everything, making his interrogator furious. He was beaten up and tortured but remained calm. He was shackled and beaten up with cudgels, only to be thrown back in his cell, bleeding and unconscious. His trial was to take place on February 3rd, 1945 but the session was adjourned due to a bombing attack on Berlin that day. Von Schlabrendorff was taken to the air raid shelter; Freisler went back to the courtroom to retrieve some legal documents, among them Von Schlabrendorff’s file but he was killed when the building took a direct hit. Subsequently Von Schlabrendorff was transferred from one concentration camp to the other and was liberated in Dachau on May 4th, 1945.

Generaloberst Friedrich Fromm took a special place on the list of people involved as the major conspirators had been executed on his orders. Then he felt it was time to leave. He decided to pay Goebbels a visit in order to report as he feared being suspected. On arrival at Goebbels’ home he was placed under arrest. All Goebbels said was: "You really were in a damned great hurry to get your witnesses under the earth." Fromm was executed later on.

Von Stauffenberg’s family suffered numerous victims. In addition to Claus, his brother Berthold, his uncle Nikolaus Graf von Üxküll-Gyllenband, his nephews Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Oberstleutnant Dr. Cäsar von Hofacker were arrested and executed as well. All close relatives were taken in Sippenhaft, including Von Stauffenberg’s 85 year old uncle Berthold who died in captivity. Von Stauffenberg’s pregnant wife Nina was arrested and deported to a concentration camp where she gave birth to her fifth child. The other four children were taken to a children’s home; they were to be adopted by National socialist families but this was thwarted by the ending of the war. After the war, mother and children were reunited. Nina von Stauffenberg passed away on April 2nd, 2006 at the age of 92. Konstanze, Von Stauffenberg’s youngest daughter wrote a biography of her mother in 2008.

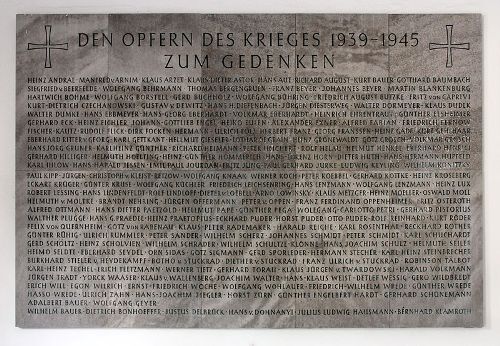

In memory

On July 20th, 1952, initiated by relatives of the conspirators, Eva Olbricht, widow of Friedrich Olbricht, laid the first stone of a monument at the Bendlerblock in memory of the conspirators. Exactly one year later the monument, a young man in bronze with his hands bound, was unveiled by the Mayor of Berlin. Two years later, the Bendlerstrasse was renamed Von Stauffenbergstrasse and another seven years on, a plague was unveiled showing the names of the four officers who had been executed by the firing squad in the night of July 21st. In 1989 the Mayor of Berlin opened a permanent exposition in the former Kriegsministerium, consisting of over 5,000 pictures and documents.Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- military authority

- Dutch military body with special authority on non-military issues (1944 – 1946).

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

Appendix: The victims

Below is a table - of necessity far from complete - listing the major persons prosecuted on occasion of the attempt on July 20th, 1944. In addition , numerous other persons were arrested, often innocent or indirectly involved. The next of kin of the most impotant persons were taken in Sippenhaft as well.

| Hans Adlhoch | Died in hospital from complications of imprisonment | 21-05-1945 |

| Generaloberst a. D. Ludwig Beck | Shot after two failed attempts at suicide | 20-07-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Robert Bernardis | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-08-1944 |

| Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff | Executed in Berlin-Moabit | 24-04-1945 |

| Gottfried Graf von Bismarck-Schönhausen | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Major Hans-Jürgen Graf von Blumenthal | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 13-10-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Hasso von Boehmer | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 05-03-1945 |

| Eugen Bolz | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Dietrich Bonhoeffer | Hanged in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-04-1945 |

| Klaus Bonhoeffer | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Oberleutnant Dr. Randolph von Breidbach-Bürresheim | Died in KZ Sachsenhausen | 13-06-1945 |

| Dr. Eduard Brücklmeier | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 20-10-1944 |

| Oscar Caminecci | Executed in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-03-1945 |

| Admiral Wilhelm Canaris | Hanged in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-04-1945 |

| Walter Cramer | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 14-11-1944 |

| Prof. Alfred Delp | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 02-02-1945 |

| Dr. Wilhelm Dieckmann | Executed in Berlin-Moabit | 13-09-1944 |

| Generalmajor z. V. Heinrich Burggraf und Graf zu Dohna-Schlobitten | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 14-09-1944 |

| Hans von Dohnanyi | Hanged in KZ Sachsenhausen | 08-04-1945 |

| Oberleutnant Hans-Martin Dorsch | Executed | 13-03-1945 |

| Hauptmann Max Ulrich Graf von Drechsel | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| Fritz Elsas | Executed in KZ Sachsenhausen | 04-01-1945 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Karl Heinz Engelhorn | Shot in Brandenburg-Görden | 24-10-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant Hans Otto Erdmann | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| General der Panzertruppen Hans-Karl Freiherr von Esebeck | Arrested, survived the war | |

| General der Infanterie z. V. Alexander von Falkenhausen | Arrested, survived the war | |

| General der Nachrichtentruppen Erich Fellgiebel | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| Generalleutnant Sebastian Fichtner | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Oberst i. G. Eberhard Finckh | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-08-1944 |

| Reinhold Frank | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Oberst i. G. Wessel Freiherr Freytag von Loringhoven | Suicide | 26-07-1944 |

| Generaloberst Friedrich Fromm | Shot in Brandenburg-Görden | 12-03-1945 |

| Hauptmann Ludwig Gehre | Hanged in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-04-1945 |

| Eugen Gerstenmaier | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Elisabeth Charlotte Gloeden | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-11-1944 |

| Erich Gloeden | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-11-1944 |

| Dr. Carl Friedrich Goerdeler | Beheaded in Berlin-Plötzensee | 02-02-1945 |

| Fritz Goerdeler | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 01-03-1945 |

| Nikolaus Gross | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Karl Ludwig Freiherr von und zu Guttenberg | Executed in Berlin-Moabit | 24-04-1945 |

| Max Habermann | Suicide | 30-10-1944 |

| Hans Bernd von Haeften | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 15-08-1944 |

| Oberleutnant d. R. Werner von Haeften | Shot in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock, Berlin | 21-07-1944 |

| Oberleutnant d. R. Albrecht von Hagen | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-08-1944 |

| Oberst Kurt Hahn | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| Generaloberst Franz Halder | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Nikolaus Christoph von Halem | Executed in Brandenburg | 09-10-1944 |

| Eduard Hamm | Suicide | 23-09-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Georg Alexander Hansen | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-09-1944 |

| Carl-Hans Graf von Hardenberg | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Ernst von Harnack | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 05-03-1945 |

| Generalleutnant Paul von Hase | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-08-1944 |

| Ulrich von Hassell | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-09-1944 |

| Theodor Haubach | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Prof. Albrecht-Georg Haushofer | Executed in Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Major i. G. Egbert Hayessen | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 15-08-1944 |

| Generalleutnant Gustav Heistermann von Ziehlberg | Shot in Berlin-Spandau | 02-02-1945 |

| SS-Obergruppenführer Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 15-08-1944 |

| Generalmajor Otto Herfurth | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 29-09-1944 |

| Andreas Hermes | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Generaloberst Erich Hoepner | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-08-1944 |

| Major Roland-Heinrich von Hösslin | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 13-10-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant Dr. Cäsar von Hofacker | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 20-12-1944 |

| Otto Hübener | Shot in Berlijn | 23-04-1945 |

| Oberst Friedrich Gustav Jaeger | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 21-08-1944 |

| Prof. Jens-Peter Jessen | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-11-1944 |

| Hans John | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Hauptmann d. R. Hermann Kaiser | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Franz Kempner | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 05-03-1945 |

| Otto Carl Kiep | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-08-1944 |

| Georg Conrad Kissling | Suicide | 04-09-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Bernhard Klamroth | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 15-08-1944 |

| Major d. R. Johannes Georg Klamroth | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 26-08-1944 |

| Hauptmann Friedrich Karl Klausing | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-08-1944 |

| Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 09-04-1945 |

| Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge | Suicide | 19-08-1944 |

| Major Gerhard Knaak | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| Dr. Hans Koch | Executed in Berlijn | 24-04-1945 |

| Heinrich Körner | Shot in Berlijn | 25-04-1945 |

| Korvettenkapitän Alfred Kranzfelder | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 10-08-1944 |

| Dr. Richard Künzer | Shot in Berlijn | 23-04-1945 |

| Elisabeth Auguste Kusnitzky | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-11-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Fritz von der Lancken | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 29-09-1944 |

| Carl Langbehn | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 12-10-1944 |

| Dr. Julius Leber | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 05-01-1945 |

| Heinrich Graf von Lehndorff-Steinort | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| Dr. Paul Lejeune-Jung | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-09-1944 |

| Major Ludwig Freiherr von Leonrod | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 26-08-1944 |

| Bernhard Letterhaus | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 14-11-1944 |

| Franz Leuninger | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 01-03-1945 |

| Wilhelm Leuschner | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 29-09-1944 |

| General der Artillerie Fritz Lindemann | Died from bullet wounds in Berlin | 22-09-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Hans Otfried von Linstow | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-08-1944 |

| Paul Löbe | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Ewald Loeser | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Ferdinand Freiherr von Lüninck | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 14-11-1944 |

| Wilhelm-Friedrich Graf zu Lynar | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 29-09-1944 |

| Hermann Maass | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 20-10-1944 |

| Oberst Rudolf Graf von Marogna-Redwitz | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 12-10-1944 |

| Michael Graf von Matuschka | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 14-09-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Joachim Meichssner | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 29-09-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim | Shot in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock, Berlin | 21-07-1944 |

| Helmuth James Graf von Moltke | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Dr. Otto Müller | Died in Berlin-Tegel | 12-10-1944 |

| Ernst Munzinger | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| SS-Brigadeführer Arthur Nebe | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 21-03-1945 |

| Wilhelm zur Nieden | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Gustav Noske | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Major i. G. Hans Ulrich von Oertzen | Suicide | 21-07-1944 |

| General der Infanterie Friedrich Olbricht | Shot in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock, Berlin | 21-07-1944 |

| Generalmajor Hans Oster | Hanged in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-04-1945 |

| Friedrich Justus Perels | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Erwin Planck | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Kurt Freiherr von Plettenberg | Suicide in Berlin | 10-03-1945 |

| Dr. Johannes Popitz | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 02-02-1945 |

| Dr. Cuno Raabe | Arrested, survived the war | |

| General der Artillerie Dr. phil. h.c., Lic.theol. Friedrich von Rabenau | Executed in KZ Flossenbürg | 12-04-1945 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Karl Ernst Rahtgens | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-08-1944 |

| Prof. Adolf Reichwein | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 20-10-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Alexis Freiherr von Roenne | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 12-10-1944 |

| Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel | Suicide in Blaustein | 14-10-1944 |

| Generalstabsrichter Dr. jur. Karl Sack | Hanged in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-04-1945 |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Joachim Sadrozinski | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 29-09-1944 |

| Anton Saefkow | Executed in Brandenburg an der Havel | 18-09-1944 |

| General der Panzertruppen Ferdinand Schaal | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Major Adolf-Friedrich Graf von Schack | Shot in Brandenburg-Görden | 15-01-1945 |

| Oberleutnant Fabian von Schlabrendorff | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Prof. Rüdiger Schleicher | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Ernst Schneppenhorst | Executed in Berlin-Moabit | 24-04-1945 |

| Dr. Otto Schniewind | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Oberst Hermann Schöne | Executed in Brandenburg-Görden | 15-01-1945 |

| Rittmeister d. R. Friedrich Scholz-Babisch | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 13-10-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant Werner Schrader | Suicide | 28-07-1944 |

| Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 10-11-1944 |

| Oberleutnant d. R. Fritz-Dietlof Graf von der Schulenburg | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 10-08-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Georg Schulze-Büttger | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 13-10-1944 |

| Ludwig Schwamb | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Ulrich Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin von Schwanenfeld | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-09-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant Ulrich Freiherr von Sell | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Oberstleutnant i. G. Günther Smend | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-09-1944 |

| Generalleutnant Dr. Hans Speidel | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Franz Sperr | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| Oberst Wilhelm Staehle | Shot near Berlin-Moabit | 23-04-1945 |

| Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 10-08-1944 |

| Oberst i. G. Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg | Shot in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock, Berlin | 21-07-1944 |

| Generalmajor Hellmuth Stieff | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 08-08-1944 |

| Theodor Strünck | Executed in KZ Flossenbürg | 09-04-1945 |

| General der Infanterie Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel | Hanged in Berlin-Plötzensee | 30-08-1944 |

| Generalmajor Siegfried von Stülpnagel | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Generalleutnant Fritz Thiele | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 04-09-1944 |

| Major i. G. Busso Thoma | Executed in Berlin-Plötzensee | 23-01-1945 |

| General der Infanterie Georg Thomas | Arrested, survived the war | |

| Generalleutnant Karl Freiherr von Thüngen-Rossbach | Shot in Brandenburg-Görden | 20-10-1944 |

| Oberstleutnant Gerd von Tresckow | Executed in Berlin-Moabit | 06-09-1944 |