Prologue

This weak and willing puppet handed the army, the instrument of aggression, to the party and directed it in its criminal actions.

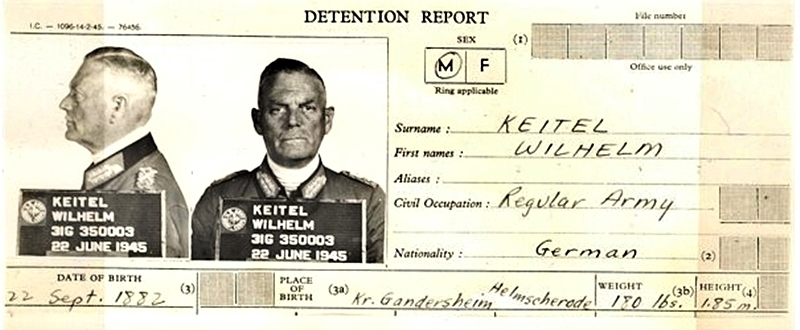

This is how Robert H. Jackson, American chief prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, described Wilhelm Keitel; during the war the head of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW or supreme command of the Wehrmacht) and generally known as a yes man and lickspittle. Who was this army commander who followed Hitler's orders almost slavishly and how much power did he have? In this article, these questions shall be dealt with.

Early years up to the seizure of power by the Nazis

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel was born on September 22, 1882 in Helmscherode in the German federal state of Brunswick, to Carl Keitel and Apollonia Vissering. He came from a characteristic Prussian family where virtue and obedience took high priority. His father was a middle class farmer, an independent landowner, just like many other of their relatives. Wilhelm spent his youth on the family estate. His mother passed away in 1888 shortly after having given birth to his younger brother Bodewin. During the first years, Wilhelm received schooling at home. Later on he attended the Humanistic Gymnasium in Göttingen. His school records were average.

Wilhelm dreamed of becoming a farmer like his father. This however was not to be as his father wanted to continue running the farm by himself. After his final exams, he therefore enrolled in the German army, in the Niedersächsischen Feldartillerie-Regiment 46 in the rank of Fahnenjunker (cadet). In prison, during the Nuremberg Trial, he told psychiatrist Leon Goldensohn he had opted for a military career as he could not earn much money in farming. A year after entering service, Keitel was promoted to Leutnant (Lieutenant), in 1908 to Regimentsadjudant (regimental adjutant) and in 1910 to Oberleutnant (2nd Lieutenant). On April 18, 1909 he married Lisa Fontaine, daughter of a real estate owner. The marriage would produce 6 children one of which passed away at a tender age.

Shortly after the outbreak of WW 1, in September 1914, Keitel was injured on his lower left arm by a piece of shrapnel at the front in Belgium. Following his recuperation, he was promoted to Hauptmann and was put in command of an artillery battery. In the same year, he made the acquaintance of Werner von Blomberg, Major, at the time and the future Minister of War. In the spring of 1915 he started training as an officer within the General Staff and subsequently he was appointed Erster Generalstabsoffizier (1st officer of the General Staff) of the 19. Reserve-Division in 1916. This made him one of the youngest staff officers in the German army. Keitel spent a large part of the war behind the front, hence he was spared the misery of the trenches for a large part. In 1918, serving in the Marine Kommando Flanders (navy command Flanders) he took part in the battle for Namur and witnessed the end of the war in Flanders.

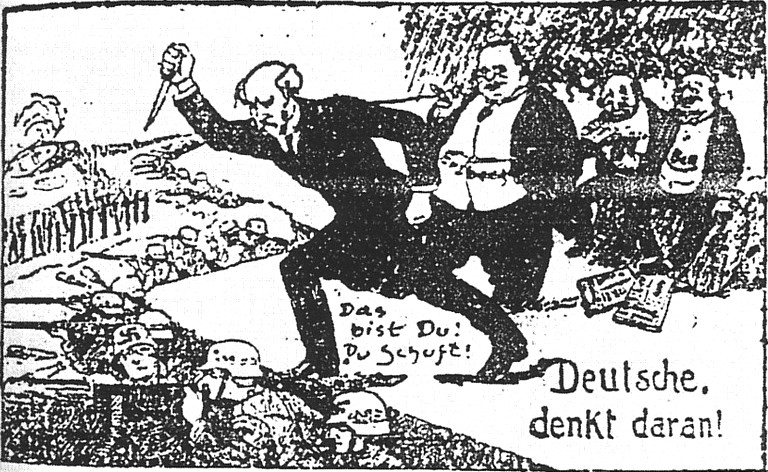

Keitel was shocked by the fall of the German Empire and the outbreak of revolution in Germany. He did not realize this was because Germany had lost the war. He was of the opinion that Germany had lost the war as a result of the Socialist revolution, the so-called stab-in-the-back legend. He wrote to his wife: "Thank God we are still young enough to restore what was destroyed in a few days of boundless stupidity."

After the war he once more considered taking over his father's farm. His family however did not agree to this and his wife had no wish to be married to a farmer. Keitel remained active in the strongly depleted German army, now called the Reichswehr. In his own words, he was forced to do so as his wife had lost all of her money because of the hyperinflation that had developed in the Weimer Republic after the war. He found employment for 3 years teaching tactics at the Kavalerieschule in Hannover. Thereafter he became active within the staff of 6. Preussisiches-Artillerie-regiment. In 1923 he was promoted to Major. From 1925 to 1927 he was Gruppenleiter in the Heeres-Organisationsabteilung (T-2) in the Truppenamt, part of the Reichswehrministerium (Department of the Reichswehr) which was in fact a continuation of the Generalstab of WW1. In 1927, he was appointed commander of II. Abteilung of the 6. Preussisches Artillerie-Regiment. His promotion to Oberstleutnant followed in 1929.

Between October 1929 and October 1933 Keitel was active again in the Reichswehrministerium, this time as head of a department. In this capacity he was also involved in the expansion and enlargement of the army, which was strictly forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. To this end he traveled to the Soviet Union where the Reichswehr operated a secret training facility. It is said he was greatly impressed by the organization of the Communist country. His superiors described him as a conscientious and diligent staff officer.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Reichswehr

- German army during the Weimar republic.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- WW1

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

Images

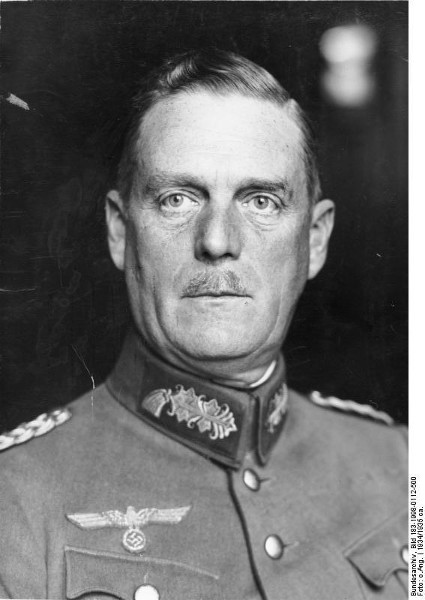

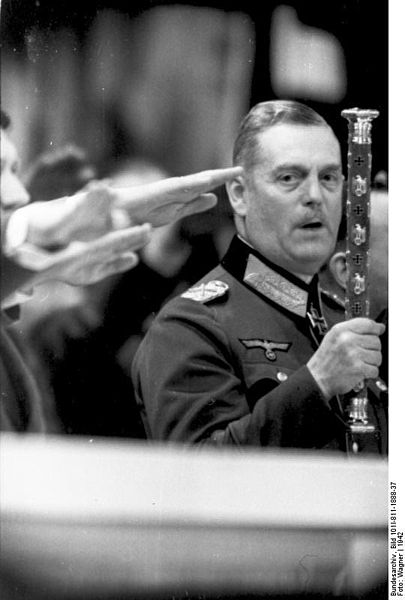

Wilhelm Keitel in the rank of "Generalfeldmarschall" in 1940. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L18173 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Wilhelm Keitel in the rank of "Generalfeldmarschall" in 1940. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L18173 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.The years of peace in Nazi Germany

When Adolf Hitler (Bio Hitler) was appointed Reichskanzler on January 30, 1933, Keitel was in a Czech sanatorium in the Tatra mountains recuperating from a heart attack and a double pulmonary inflammation. During the Nuremberg Trial, he declared about the seizure of power by Hitler: "We openly and honestly welcomed the fact that the Reichsregierung was now headed by a man who was determined to establish an era that would free us from the prevalent miserable circumstances at the time." In July 1933 he met Hitler for the first time. His wife later wrote: "He was really impressed, he was so enthusiastic about Hitler.

In October 1933, Keitel, holding the function of Artillerieführer III, was named second in command of 3. Division. Keitel publicly advocated a politically neutral Reichswehr. He sympathized with Hitler and the NSDAP though. After he had heard Hitler deliver a speech on the Tempelhofer Field in Berlin, he was deeply impressed. Keitel claimed he had never been a member of the NSDAP. Later on however, an application form, completed by him, was discovered in the archives. He also received the Goldenes Parteiabzeichen in 1939, allegedly on occasion of the German invasion of Czechoslovakia.

In 1934 his father Karl passed away. His son, the officer Keitel now had the opportunity to leave the service and take over the farm. His superiors however persuaded him to remain in the army by offering him the command over a division. March 1, 1934 saw Keitel promoted to Generalmajor. In October of the same year, in the capacity of Infanterieführer VI, he was put in command of the 22. Infanterie-Division. Later on he described the period in which he commanded a division as the happiest phase of his career as he was independent of political issues and enjoyed much freedom. In 1935, Hitler declared he would denounce the Treaty of Versailles and openly proceeded to re-arm Germany. Keitel supported this policy wholeheartedly.

On October 1, 1935, Keitel was given a new function, being named Chef des Wehrmachtsamtes within the Reichskriegsministerium. Here he became the right hand man of the Minister of War, Feldmarschall Werner von Blomberg. In his new function, Keitel attempted to enhance the coordination between the Heer, the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe by creating a communal command organ. This was out of pure necessity. The command structure used at the time dated back to the First World War and took no account of the changing role of the navy and the increasing importance of the air force. This initiative however met opposition from the generals, especially from General Ludwig Beck, chief of the General Staff, who did not want to let the privileged position of the army slip out of his hands. Hermann Göring (Bio Göring), commander of the newly formed Luftwaffe, remarked he did not care whether he was under the command of Keitel or not. He took orders only from Hitler anyway. This initiative was therefore shelved for the time being. It did not prevent Keitel from being promoted to Generalleutnant on January 1, 1936 and subsequently to General der Artillerie on August 1, 1937.

In February 1938, a massive restructuring took place within the army leadership. After coworkers of Arthur Nebe (Bio Nebe), chief of the German Kriminal Police (Kripo) had discovered that Werner von Blomberg's new spouse had posed for pornographic pictures and she was on police records as a prostitute, the Minister was forced to resign. His most probable successor, Generaloberst Werner von Fritsch, supreme commander of the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH, supreme command of the army) was discredited as well after phony accusations of homosexuality had been brought against him, partly instigated by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler (Bio Himmler).

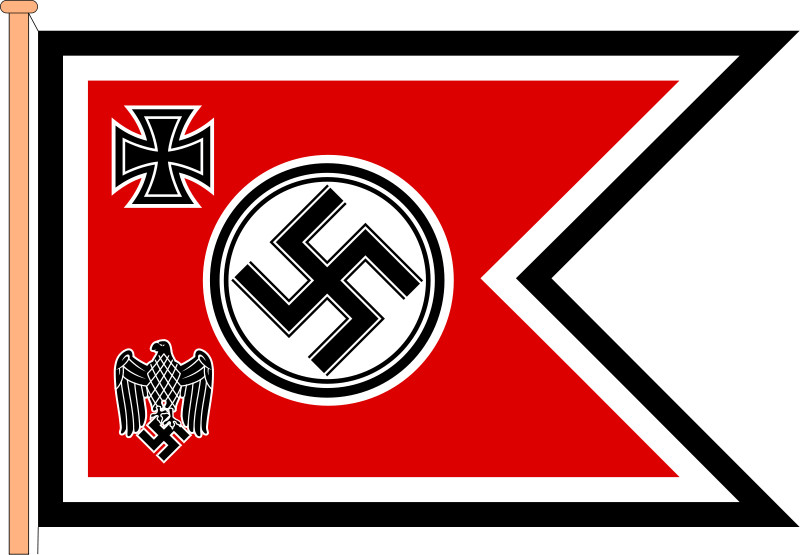

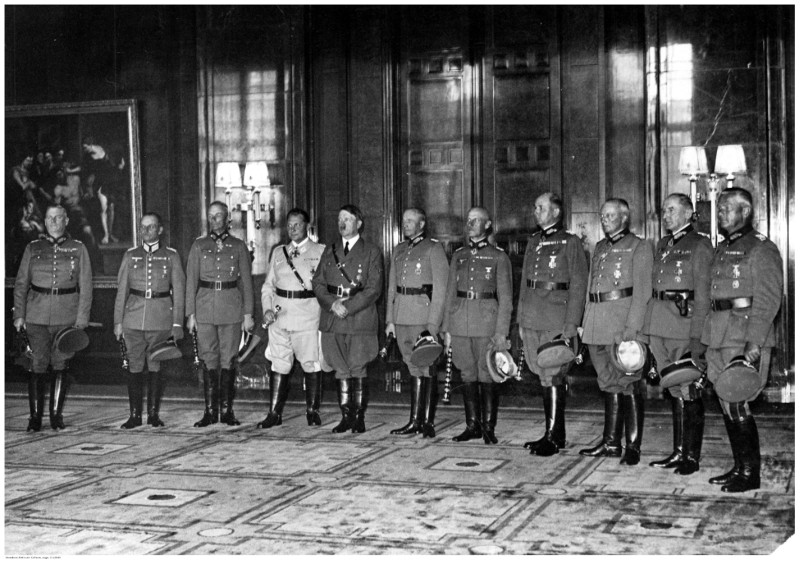

After the Von Blomberg-Fritsch affair Hitler decided, accepting a proposal by Propagandaminister Joseph Goebbels (Bio Goebbels) and allegedly by Von Blomberg as well, to take command over the Wehrmacht himself in order to re-organize the leadership of the armed forces. Hitler used this opportunity to discharge or transfer people from outside the army leadership as well and replace them by people more dedicated to Nazism. Keitel had been introduced to Hitler by Von Blomberg. Keitel claimed he had met Hitler just three times prior to February 1938. Hitler now indicated Keitel would become his sole military advisor and appointed him Chief of the OKW, a recently established body that actually took the place of the Reichskriegsministerium. The submissive Generaloberst Walter von Brauchitsch (Bio Von Brauchitsch) was appointed supreme commander of the OKH. In his new function, Keitel was responsible for providing soldiers and equipment, espionage and the care for Prisoners-of-War. In fact, his most important role consisted of forwarding Hitler's orders to his generals. Many military (including Keitel as he claimed himself) were stunned over the appointment of this unknown man to this function. Hitler probably selected Keitel deliberately for this important position because he knew that this weak general would offer little opposition. As Alfred Jodl, chief of the Wehrmachtsführungsstab remarked at the Nuremberg Trial: "There was no and there could not be an influential man beside Hitler."

Keitel was also given a seat on the Ministerrat für die Reichsverteidigung (Ministerial council for state defense). He was no Reichsminister officially but he held the same rank. On occasion of the Von Blomberg-Fritsch affair, an officer on the Generalstab remarked: "Today they have broken our back.". Many of the (senior) officers in he Wehrmacht indicated Keitel did not possess the character and the stature for someone with the power of a minister. Wolfgang Brocke, a transport officer remarked in a television documentary that a job as a museum director was more than he could handle. The establishment of the OKW however proved to be no solution for the divided command structure within the armed forces. Throughout the entire war, conflicts would keep popping up between the OKW and the commanding entities of the other branches of the armed forces, in particular the OKH. This power structure of vaguely defined and partly overlapping spheres of authority by the way was characteristic for the Hitler regime.

From February 1938 onwards, Keitel remained in Hitler's vicinity almost continuously. The Führer discussed military issues with him but he also served other purposes. During negotiations in Hitler's Berghof on the Obersalzberg on February 10, 1938, which preceded the Anschluß of Austria to Germany, Hitler summoned Keitel just to intimidate the Austrian Prime Minister Kurt Schuschnigg with the general's presence. This move made a strong impression on the Austrian Chancellor. March 12, 1938 saw the actual Anschluß of Austria to the Third Reich.

On March 20, 1938, Hitler ordered Keitel to draft a plan for the attack on Czechoslovakia. There was discussion about creating an incident, like the murder of the German Minister of Foreign Affairs in Prague, in order to justify the attack. On May 20, Keitel presented a concept, drawn up by his direct subordinate Oberst Alfred Jodl, which largely consisted of Hitler's own views. On May 30, he signed the decree for Fall Grün of which the preparations had to be completed by October 1, 1938. After the war, Keitel claimed the Wehrmacht had not been ready for an attack on the Czech fortifications at that time. This turned out to be unnecessary because pursuant to the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938, the Sudetenland was signed over to Nazi-Germany. Three weeks later, the remaining parts of Czechoslovakia were occupied and the country became a fascist satellite state of Germany.

On May 23, 1939, Keitel attended a secret conference with Adolf Hitler, Hermann Göring and Großadmiral Erich Raeder (Bio Raeder), commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine at which Hitler announced to attack Poland at the first suitable opportunity. During this meeting he also announced he would ignore the neutrality of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg. During the Nuremberg Trial, Keitel claimed he had protested against these plans. In his opinion, the German armed forces were not ready for the campaign against Poland, in particular if France was to attack in the West. Whether he actually protested against this plan during this meeting is doubtful. There is no supporting evidence for this thesis.

Preparations for war continued. On August 25, Keitel passed on Hitler's order that the marching order against Poland should be revoked as negotiations were under way with Poland with Great Britain acting as mediator. This last attempt at mediation failed however.

Definitielijst

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Heer

- German army or land forces. Part of Wehrmacht together with “Kriegsmarine” and “Luftwaffe”.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Kripo

- Kriminalpolizei. Criminal investigation agency. Ordinary civilian police of Nazi Germany.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Reichswehr

- German army during the Weimar republic.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Attack on Poland and the West

September 1, 1939, the German army marched into Poland, triggering the Second World War. The campaign proceeded with horrendous crimes on German side. September 12, 1939, Vizeadmiral Canaris, chief of the Abwehr, inquired whether it was true that large scale executions (by the Einsatzgruppen) were being carried out in Poland and the nobility and the clergy were to be exterminated. Keitel indicated that the Führer had decided accordingly and that the Wehrmacht was in no way responsible for it. Later on he claimed he had only repeated Hitler's words. The Abwehr was part of the OKW to which Canaris also belonged. This way Keitel and Canaris were in contact with each other frequently. They also had a friendly relationship. Regular soldiers of the Wehrmacht in Poland also made themselves guilty of murder, rape and plunder.

Keitel attended a meeting on October 17, 1939 where Hitler indicated what policy he would apply against the Polish population. Hitler himself characterized this as: "the work of the devil." The policy entailed issues such as keeping the standard of living low. The region served only to provide laborers. Hitler remarked further: "Governing this area will enable us to cleanse the Reich of Jews and Pollacks." On December 12, Hitler discussed the invasion of Denmark and Norway with Alfred Jodl, Keitel and Erich Raeder. The latter advocated such an attack because if not, the British were likely to occupy these countries and hence disrupt further transport of iron ore to Germany. On January 12, 1940, these plans were placed under the direct and personal control of Keitel and Alfred Jodl of the OKW. Operation Weserübung was launched on April 9 under command of General der Infanterie Nikolaus von Falkenhorst. Denmark was captured in a single day. The battle for Norway took longer but the German forces soon gained the upper hand. The attack was a fine example of a well coordinated deployment of land, sea and air forces. This clearly confirmed the advantages of an overall command structure. Contrary to the Allies however, the Germans would make little use of this method for the remainder of the war.

Even though the fighting around Narvik was still raging, Fall Gelb, the invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg and France was launched on May 10, 1940. The OKW had only made a small contribution to the planning of this attack. The OKH and more in particular Generalleutnant Erich von Manstein were responsible for the plans of this operation. France was brought down to her knees in less than 6 weeks. Wilhelm Keitel, along with a few other high ranking Nazis including Rudolf Hess were present at the signing of the armistice with France on June 22, 1940, in a railway carriage in the Forêt de Compiègne. Keitel read the conditions of the armistice which was subsequently signed by the German and French delegates.

During the victory celebrations in Berlin on July 6, Keitel described Hitler as "the greatest warrior of all times" (the term Größter Feldherr aller Zeiten, in short Gröfaz was to become a nickname for Hitler after the tide of war had turned against Germany). On July 19, Hitler promoted Keitel to Generalfeldmarschall. Keitel however enjoyed little respect from his colleague-generals. Due to his compliance to Hitler they soon nicknamed him lakeitel (a combination of lackey and Keitel). Hitler though appreciated the obedient general very much. On September 22, 1942 he was given a bonus of 250,000 RM and in October 1944 he was presented with a forest area of 608 acres in Lamspringe in the federal state of Niedersachsen, valued at 739,240 RM. He later told prison psychiatrist Leon Goldensohn he had hoped to settle down on his estate after the war.

Right after the armistice with France, Hitler talked to Keitel and Jodl about an attack on the Soviet Union. Compared with the campaign in the west, this would, in his own words, be no more than child's play (Sandkastenspiel). On December 18, 1940, Hitler issued Weisung 21 in which he ordered the Wehrmacht to prepare itself for an attack on the Soviet Union.

In February 1941, Keitel received 2 memoranda drafted by General der Infanterie Georg Thomas, head of the Wirtschaft und Rüstungsamt, co-drafted by the former Minister of Economic Affairs Hjalmar Schacht and others, warning that Germany was not ready for war against the Soviet Union, among other things due to the limited supply of fuel and rubber. Despite the explicit request of Thomas, Keitel did not forward this memo to Hitler. Prior to Operation Barbarossa, Thomas also submitted a fairly accurate estimate of the armaments production of the Soviet Union. He also stated that the capture of the European part of the Soviet Union did not necessarily result in the downfall of the industrial production of the country as a whole. Adolf Hitler rejected these estimates because they did not match the image he had of the Slavische Untermensch (Slavic subhuman). Keitel disallowed the Wirtschaft und Rüstungsamt from then on to submit information to the Führer he might not like.

All orders from Adolf Hitler pertaining to the armed forces bore Keitel's signature. In his capacity of Chef des OKW, he was involved in all important military decisions although in his own words, he had no influence on them. To Goldenstein he claimed: "I did not have troops at my disposal, no power. I was bound by my oath. I did not have the slightest idea of Hitler's intentions." Furthermore he stated: "Being the Führer's assistant for the operational issues he planned and which he ordered, we – the OKW – had nothing to do with political motives in the background. That was not our job. I cannot and will not defend the game of higher politics. It would also not be correct if I were to say I knew nothing about all of this. The truth is that as far as our work was concerned, we had nothing to do with these matters and the Führer explicitly told us that we had nothing to do with political matters." According to Keitel, political measures also included the guarantee of neutrality Germany had made to various west-European countries.

Adolf Hitler could not prepare for war all by himself though. He needed the cooperation of the military. Because of this cooperation they made themselves accomplices. Keitel and the other high ranking military knew that waging a war of aggression was a crime in itself, also according to the Kellogg-Briand Pact, an international pact signed in 1928 in which a number of West-European states condemned war of aggression.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Untermensch

- In the Nazi philosophy the opposite of a superior human being (Übermensch), a human being with superior mental and physical characteristics.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

German troops destroying a boom somewhere on the border between Poland and Germany (re-enacted) Source: Wikipedia.

German troops destroying a boom somewhere on the border between Poland and Germany (re-enacted) Source: Wikipedia. Generaal Keitel driving through the steets of Lodz, shortly after the town was captured by German troops Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1985-0930-502 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Generaal Keitel driving through the steets of Lodz, shortly after the town was captured by German troops Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1985-0930-502 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Keitel in front of the railway car in Compiegne, where the armistice after WW 1 was signed and the surrender in 1940 Source: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-P50287 / Weinrother, Carl / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Keitel in front of the railway car in Compiegne, where the armistice after WW 1 was signed and the surrender in 1940 Source: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-P50287 / Weinrother, Carl / CC-BY-SA 3.0.War Crimes and Operation Barbarossa

On March 13, 1941, Keitel signed the plan for Operation Barbarossa. Deployment of the Einsatzgruppen was not mentioned in so many words but it had probably been discussed with SS chief Heinrich Himmler. The plan also stipulated that the Reichsfühere-SS (Himmler) was charged with special duties (Sonderaufgaben), a euphemism for mass murder.

On June 6, 1941, Keitel signed the Kommissarbefehl, entailing that any political Kommissar of the Red Army who had been taken prisoner was to be executed on the spot. Keitel himself had issued this order on occasion of a speech by Hitler to 200 Wehrmacht generals on March 30. A number of generals, including Fedor von Bock (Bio Von Bock) and Gerd von Rundstedt (Bio Von Rundstedt) urged Walther von Brauchitsch to protest against this to Hitler. He did not do so however. On June 16, Keitel ordered the economic measures by Hermann Göring to be applied by all units in the occupied areas. He wrote in this order: "Exploitation of the Soviet Union must be carried out on a large scale […]" On July 23 he issued an order to the effect that draconic measures had to be taken to maintain order in the secure areas, the sectors behind the front.

During the first months of Operation Barbarossa, the Germans took millions of Russians prisoner. The OKW was in charge of them. In an order of September 8, 1941, Keitel indicated they should not be treated according to the Geneva Convention. When Wilhelm Canaris put up protest, Keitel stated that the complaints of the Abwehrchef originated from the military idea of chivalrous warfare. These measures served to destroy an ideology and therefore he (Keitel) could approve and back the measures. According to Albert Speer, Keitel protested against French and other western prisoners-of-war who were deployed in the armaments industry in violation of the Geneva Convention. As far as Russian PoWs were concerned, he couldn't care less. On February 20, 1942, Alfred Rosenberg (Bio Rosenberg), Minister of the occupied areas in the East, wrote in a letter to Keitel that out of 3,6 million PoWs only a few thousand were still capable of work. As a result of the bad conditions, 3 million Russian PoWs died in German prison camps.

On September 12, 1941 Keitel wrote in a secret instruction to the German army: "The fight against Bolshevism demands ruthless and energetic action, especially against Jews, the main instigators of Bolshevism." Keitel's own attitude towards Jews is not entirely clear though. A number of his orders were anti-Semitic. On the other hand he claimed having defended Jews, decorated in the First World War, to save them from persecution. These efforts were unsuccessful though.

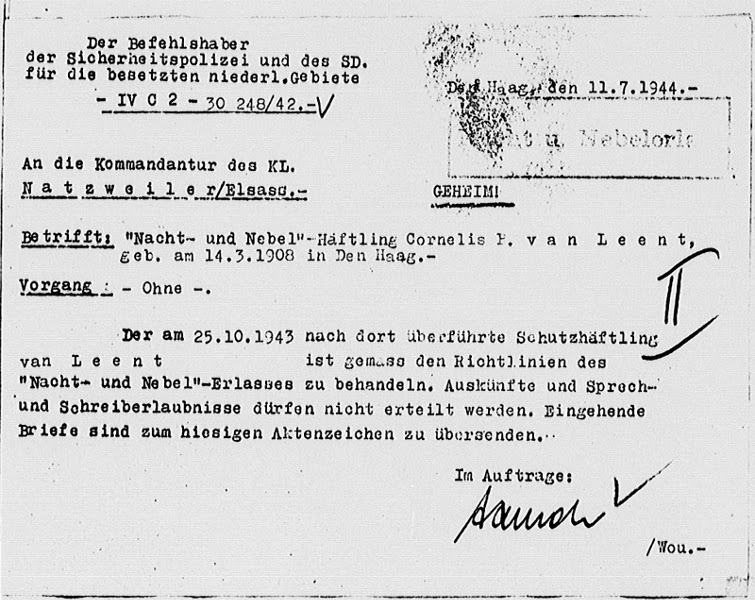

On December 7, 1941, Keitel signed the "Nacht und Nebel" order, Implying that political prisoners and members of the resistance could be deported to concentration camps without trial. In it he wrote: "In such cases a labor camp or even life long forced labor will be considered a sign of weakness. A definite and deterrent method can only be found in the death penalty or in measures which leave family members and the rest of the population in the dark as to the fate of the culprit. Deportation to Germany serves this purpose." According to Keitel, this method was decided on because resistance in the occupied areas increased and therefore many units had to be kept stationed in the west out of necessity. Adolf Hitler really didn't like resistance fighters being tried in public. Keitel also claimed this order was meant for the Wehrmacht only and during the Nuremberg Trial, he was highly amazed that during the war, this order had been carried out on a large scale by the German police and that persons had been liquidated pursuant to this order.

Keitel issued more orders that were in flagrant violation of the laws of warfare. On occasion of the increasingly fierce resistance of the partisans in Yugoslavia, occupied by the Germans in May 1941, he issued the Sühnebefehl on September 16, 1941, meaning that for every single German killed by the resistance, 50 to 100 Communists were to be executed in reprisal. He remarked that in the East, a human life was worth even less than nothing. This was followed up on December 16, 1942, by the Banditenbekämpfungbefehl of the same scope. He also issued an order to the effect that attacks by German military on civilians were to remain unpunished.

In order to suppress the budding resistance by the subjected population, the German regime introduced a ruthless repression. Keitel also involved the Wehrmacht in these measures. On October 1, 1942 he issued an order to the effect that Wehmachtcommanders in the occupied areas should chose hostages among the civilian population to be executed in reprisal in case of armed actions by the resistance. In answer to questions by Josef Terboven, Reichskommissar in Norway, he answered it was best to keep firing squads at hand. In the Netherlands for instance, a camp for hostages was established in Sint-Michielsgestel.

The Allies, and in particular the British attempted by means of sabotage, carried out by smaller military units, to make it hard on the Germans by blowing up power plants, vessels and such. Among the examples are for instance the raid on Bruneval and Operation Frankton. The Germans came down hard on these saboteurs. On August 4, 1942, Keitel issued an order to the effect that captured paratroopers were to be handed over to the Security Service (SD) Keitel was also involved in the issuance of the Kommandobefehl on October 18, 1942. It implied that captured commandoes were to be executed immediately. In November 1942, this order was applied for the first time to a number of British military who had been captured during a raid on the heavy water plant in Vemork (Operation Freshman). In answer to questions by Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, supreme military commander in Norway, Keitel confirmed Hitler's order and the prisoners were subsequently tortured and executed. On October 30, 1942, 7 British and Norwegian commandoes had been executed who had launched an attack on the power plant at Glomfjord, Norway on September 21. At the time of the attack the order had not yet been issued officially, making it invalid. Hitler was informed of the incident in a report signed by Keitel. During the Nuremberg Trial, Jodl called it a completely illegal action he could or would not justify. After the invasion in Normandy, Keitel once again confirmed the Kommandobefehl. After the war, he claimed he had fostered doubts about the legality of the order but he did nothing to stop the executions.

After the war, during the Nuremberg Trial, Generalfeldmarschall Ewald von Kleist stated: "Many of Keitel's orders were wrong and criminal. They were the orders of a meek follower of Hitler." Keitel was not stupid, though. He took an IQ test in Nuremberg after the war and reached a score of 129.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Reichskommissar

- Title of amongst others Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the highest representative of the German authority during the occupation of The Netherlands.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Wilhelm Keitel is congratulated by Hitler at his 40th service anniversary, March 9, 1941 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J1117-500-002 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Wilhelm Keitel is congratulated by Hitler at his 40th service anniversary, March 9, 1941 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J1117-500-002 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Keitel, Hitler and Von Brauchitsch discussing the situation on the Balkans aboard a railwaycar, April 1941 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L18678 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Keitel, Hitler and Von Brauchitsch discussing the situation on the Balkans aboard a railwaycar, April 1941 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L18678 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. A discussion on the situation in Russia, October 1941. F.l.t.r. Wilhelm Keitel, Adolf Hitler, Walther von Brauchitsch, Friedrich Paulus. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-771-0366-02A / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

A discussion on the situation in Russia, October 1941. F.l.t.r. Wilhelm Keitel, Adolf Hitler, Walther von Brauchitsch, Friedrich Paulus. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-771-0366-02A / CC-BY-SA 3.0.Personality

Keitel was a military man first and foremost. Apart from his work, he had no hobbies. Historian Anthony Beevor characterizes Keitel as a not very intelligent nincompoop; Guido Knopp calls him a spineless yes man. Keitel evidently was a man of weak character who never took responsibility. If something went wrong, it was always because of circumstances outside his grasp. For instance, Keitel had the psychological tests of the Wehrmacht abolished after one of his sons was not admitted to an officers exam as he had failed the test. Obedience and loyalty were his main virtues. He claimed after the war Hitler would have had him murdered if he had not obeyed him. He claimed he did not always agree with Hitler's orders but carried them out nonetheless. He also claimed he had considered to resign on three occasions. When he and Hitler had a disagreement over the offensive in the West in 1939, he allegedly asked Hitler to relieve him of his function. Hitler wanted to launch the attack – Fall Gelb - in the winter of 1939-1940. His generals were against it because of the disadvantages involved in an attack in the winter with its bad weather and long nights.

In the fall of 1940, Keitel allegedly drafted a memorandum, advising against an attack on the Soviet Union as the German military was not yet ready and because this offensive would violate the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. Hitler would have denounced this memo after which Keitel requested to be transferred but it was rejected. Keitel declared this during his examination in Nuremberg. The memo was never found although Joachim von Ribbentrop, Minister of Foreign Affairs under Hitler, did confirm Keitel had discussed this proposal with him in August or early September 1940. Alfred Jodl also stated during the Trial that Hitler and Keitel had a heated argument in November 1941. It is not clear over what, it was probably over the defeat in the battle for Moscow. According to Jodl, Hitler declared: "Here I deal with blockheads only." At the time Keitel wrote his letter of resignation and he even seemed to have considered suicide but Jodl stopped him. Hitler did not want to let go his loyal lackey and refused to discharge him. Jodl also testified: "As matters stood, we were all involved in a life and death struggle and eventually an officer could not stay home knitting socks. Time and again it was our devotion to duty that got the upper hand."

During his examination at the Nuremberg Trial, Hermann Göring said about Keitel: "His work was surely very ungrateful and difficult. I remember he once approached me and asked if I could arrange things so he could have a front command; that he, although he had the rank of feldmarschall he would be happy with a division as long as he could leave since he received more scorn than thanks. Whether his task was ungrateful or appreciated did not matter, I told him; he had to do his duty whenever the Führer ordered him to." Furthermore, Göring testified: "I know that after the downfall, a lot of generals took the view Keitel had been a typical yes man. I would be very interested to meet people today who would call themselves no men."

The losses of war did not pass the Keitel family by. His youngest son Hans-Georg was killed in action on July 18, 1941, near Smolensk as a result of injuries sustained during a Russian air raid. His daughter died in 1942 from a pulmonary infection. Another son, Major Ernst Wilhelm was reported missing at the Eastern front in 1943 and it was assumed he had been killed. His eldest son, Obersturmbannführer in the Waffen-SS, Karl Heinz, was wounded in December 1944 and was made a prisoner-of-war at the end of the war by the Russians.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- non-aggression pact

- Agreement wherein parties pledge not to attack each other.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Relation to Hitler

On June 24, 1941, Adolf Hitler and his personal staff, including Keitel and Jodl, took up residence in his new headquarters in Rastenburg, eastern Prussia, the Wolfssschanze (Wolves Lair). In the Wolfsschanze, a strict daily routine was maintained. At noon there was the staff meeting between Hitler, Keitel, Jodl and other officers. Afterwards, lunch was served. Jodl sat to the left of Hitler while Keitel sat across from him. The second staff meeting, with less people in attendance, took place at 18:00 and was chaired by Alfred Jodl. These meetings often lasted 2 hours or more.

Hitler steadily increased his grip on the Wehrmacht. After the battle for Moscow had been lost in early December 1941, Walter von Brauchitsch was sacked on December 19, and Hitler took command of the army himself. Other generals like Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, commander of Heeresgruppe Mitte (Armygroup Center) en Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, commander of Panzergruppe 2 were sacked along with dozens of other generals and lower commanders for having failed in Hitler's eyes. The clerical duties of Von Brauchitsch were transferred to Keitel. This actually meant that the OKH was now answerable to the OKW of Keitel and Jodl. Instead of merging both staffs, Hitler ordered the OKH to deal with the fighting in the East while the OKW was charged with the fighting in the West. This included the occupied western-European countries and North-Africa. In June 1942, Hitler split the southern army group in Russia. Heeresgruppe A was ordered to capture the oil fields in the Caucasus while Armygroup B advanced on Stalingrad.

In order to be closer to the front, Hitler and his entourage moved to a headquarters near Vinnitsa in the Ukraine named Werwolf in July 1942. Initially, meetings were held at the headquarters of the Wehrmacht Staff. When in 1942 the tide of war began to turn, the atmosphere grew grimmer. From then on, meetings took place in Hitler's barracks and everything was recorded as Hitler complained about his orders being misinterpreted. On September 10, 1942, Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm List was sacked as commander of Heeresgruppe A as his offensive in the Caucasus had not yielded the desired results and because Hitler claimed Von List had disobeyed his orders. Hitler subsequently took over his function. Generaloberst Franz Halder was also relieved of his function as Generalstabschef des Heeres on September 24 and replaced by Generaloberst Kurt Zeitzler, a yes man with a rock solid trust in the Führer. According to historian Ian Kershaw the disposal of the chief of staff as an empty cartridge "symbolizes the final destination of the capitulation of the once so mighty army leadership from the powers with which it had united itself in 1933." In those days, Hitler seemed to have played with the idea to fire both Jodl and Keitel and to replace them by Friedrich Paulus and Albert Kesselring. Owing to the steadily deteriorating military situation at Stalingrad and in the Mediterranean this did not come to pass, also because Feldmarschall Paulus, commander of 6. Armee, was captured after he surrendered at Stalingrad.

From the spring of 1942 onwards, the mightiest group in the Third Reich consisted of Martin Bormann, Hans Lammers, chief of the Reichskanzlei and Keitel. They isolated the Führer more and more. Albert Speer considered the isolation of Hitler from the outside world by his inner circle a major problem for the Nazi regime. This problem became particularly visible, according to the Minister of Armaments, in the relation between Hitler and his generals."Except from Keitel, who was 'his' man who only told him what he wanted to hear and from Jodl, whose power was soon restricted because of his independent thinking, Hitler did accept information but never any tactical advise.

After the battle for Stalingrad had ended in a catastrophic defeat in January 1943, Propagandaminister Joseph Goebbels called for waging "Totaler Krieg" in a speech in the Sportpalast in Berlin. All economic efforts were to be aimed at increasing war production and people not employed in sectors important for the war, were to be deployed in the armaments industry or taken up into the army. In the top of the Third Reich, characterized by the fact (at Hitler's own doing) that power was spread over mutually competing and overlapping agencies, a struggle soon arose over who was to get authority over the policy connected to total war. Initiated by Lammers, a triumvirate was established, consisting of himself, (on behalf of the Reichskanzlei), Martin Bormann (head of the Parteikanzlei) and Keitel. This committee stood above the individual ministries and departments and was tasked with coordinating all measures pertaining to total war. The agency, designated as "Dreier Ausschuß" would report directly to the Führer. This triumvirate could issue orders but was not entirely autonomous. As was the case in so many agencies, Hitler always had the final say. The committee met 11 times between January and August 1943 but did not achieve much. The ministries and other party agencies did not allow infringements on their authority. According to Speer, the members of his committee were unable to carry out their task because of their lack of technical know how.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

Images of Hitler's HQ, the Wolves Lair Source: YouTube.

Images of Hitler's HQ, the Wolves Lair Source: YouTube. The meeting on Thursday February 18, 1943, in the Sportpalast in Berlijn where Goebbels calls for Totaler Krieg (total war) against the Red menace Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J05235 / Schwahn / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

The meeting on Thursday February 18, 1943, in the Sportpalast in Berlijn where Goebbels calls for Totaler Krieg (total war) against the Red menace Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J05235 / Schwahn / CC-BY-SA 3.0.Belief in final victory, 1944

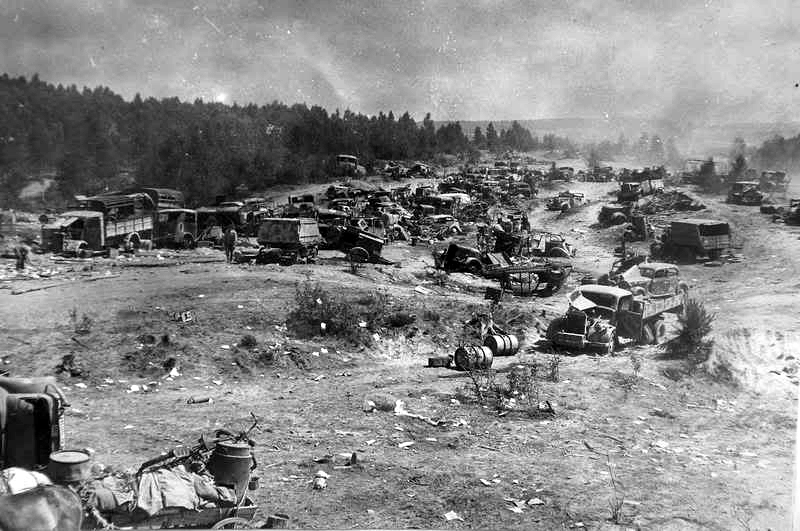

Keitel continued to believe in the genius of the Führer and in ultimate victory even when after the battle of Stalingrad, defeats on the Eastern front began to pile up. Even after the war he held his belief in the geniality of the Führer. He stated Hitler possessed a broad military knowledge and it was impossible to catch him on a mistake. In reality, Hitler made a vast number of military mistakes. His order to hold out in Festungen instead of retreating his armies to fight another day caused numerous unnecessary losses as during the battle for Stalingrad and during Operation Bagration, an offensive by the Red Army in June 1944 in Byelorussia.

After the battle of Kursk, June 1943, had ended in a catastrophe and Kharkov was recaptured by the Red Army on August 23, a number of German officers started grumbling. General der Infanterie Otto Wöhler, commander of 8. Armee wrote a critical report in which he urged that the soldiers be presented the actual facts about the general situation instead of being deluged with propaganda and hollow words. Feldmarschall Erich von Manstein supported him in this but Keitel forbade any further correspondence on the issue. All officers were to remain unconditionally loyal to the leadership instead of weakening the national will power. Keitel even threatened to hand a few critical officers over to the Gestapo. Member of the Abwehr Bernd Gisevius during the Nuremberg Trial: "It is my great wish to testify here that Feldmarschall Keitel, who was supposed to protect his officers, regularly threatened them with the Gestapo. He put pressure on these men."

In the wake of the battle for Stalingrad, a number of generals, including Erich von Manstein, suggested that Hitler should transfer leadership of the fighting on the Eastern front to a confidant. Hitler refused. According to Kershaw, he preferred the compliance of someone like Keitel over the sharply formulated counter arguments of someone like Von Manstein. Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, Inspekteur der Panzertruppen, proposed a few months later – January 1944 – to appoint another general chief of the general staff of the Wehrmacht. With this he also hinted at Keitel's discharge. Hitler rejected his proposal.

On June 6, 1944, the day of the Allied invasion in Normandy, Major Werner Pluskat of the 352. Küstendivision, stationed in the sector designated Omaha Beach by the Americans, made a phone call to Keitel. The chief of the OKW asked him what was going on. When he had heard the answer, Keitel had the Führer woken up. Meanwhile it was already late in the morning. Because Hitler had been woken up so late, it was previously impossible to dispatch 2 armored divisions, lying in reserve west of Paris to Normandy as the Führer's permission was required. When permission finally was granted, the divisions could no longer arrive in Normandy in time to hold back the invasion. After D-Day, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt warned the OKW that the Wehrmacht was unable to stop the Allied armies in Normandy. To Keitel he remarked: "You should put a stop to the entire war." Subsequently, Hitler ordered his replacement by Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge.

Propagandaminister Joseph Goebbels also voiced criticism on the military tactics and the situation in Germany where the principle of total warfare, despite his speech, had not yet been introduced. He remarked Hitler was in need of someone like a Scharnhorst or a Gneisenau, 2 famous commanders of the Napoleon era, instead of Keitel and Generaloberst Friedrich Fromm, commander of the Ersatzheer. Hitler agreed with Goebbels there were indeed weak spots in the organization of the Wehrmacht but he refused to discharge them as there were, in his view, no suitable replacements available.

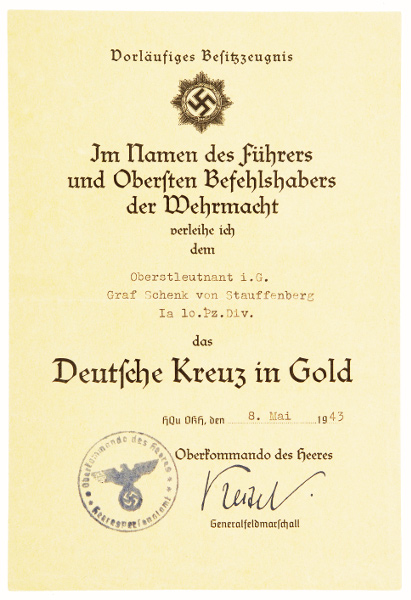

In the morning of July 20, 1944, Oberst Claus, Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg reported to Generalfeldmarschall Keitel at the Wolfsschanze in Rastenburg. From 11:30 to 12:30 Von Stauffenberg had a preliminary meeting with the chief of the OKW. In the afternoon he would, along with Keitel, attend the meeting with Adolf Hitler. Before he went in, he enquired where he could put on a clean shirt. Keitel's adjutant, Oberst Ernst John von Freyend showed him a room where he could freshen up. The officer used the isolation of this room to arm a bomb in his briefcase. The rule was that officers who entered the meeting room in the company of Keitel were not searched by the guards of the SS. Von Stauffenberg ran out of time to arm the second bomb as Von Freyend called him to the meeting which had been moved forward, due to the arrival of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini that afternoon.

As Von Stauffenberg entered the chartroom, he placed his briefcase under the table and mumbled to Keitel he had to make a phone call. A few minutes after Von Stauffenberg had left, the bomb exploded. As it was, the attempt failed. Keitel was the only person in the room who escaped the explosion unharmed, but 2 men were killed instantaneously while 2 others later succumbed to their injuries. When Hitler was on his feet again Keitel embraced him in tears and called out: "Mein Führer, Sie leben, Sie leben! (My Führer, you are alive)." Soon suspicion turned to Von Stauffenberg. Keitel called Fromm at 16:00, declared that Hitler was still alive and asked where the Oberst was. He also issued an order to all military units the effect that orders from the conspirators in the Bendlerstraße were to be disregarded.

Following this attempt and coup of July 20, 1944, Keitel issued the order to prosecute the Wehrmacht officers involved. He was a member of the Ehrenhof der Wehrmacht (honorary court) which degraded the officers involved in the attempt, including Feldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben, and discharged them from the Wehrmacht so they could be tried as civilians by the notorious Volksgerichtshof (people's court) chaired by "Justice of Blood" Roland Freisler who sentenced them to death by hanging. Keitel himself claimed he had advocated clemency for the next of kin of the conspirators. He also declared after the war he had supported Wilhelm Canaris' family financially after his arrest, which was later on confirmed by Alfred Jodl. In the wake of the attempt and coup, the former chief of the Abwehr was arrested and on April 9, 1945, he was hanged in concentration camp Flossenburg. In the attempt of July 20, Hitler saw confirmation of his view that the Wehrmacht was riddled with traitors and pessimists.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

July 15, 1944, at the Wolfsschanze and 5 days prior to the assault, Hitler greets an officer. On the left Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg, on the right Wilhelm Keitel Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1984-079-02 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

July 15, 1944, at the Wolfsschanze and 5 days prior to the assault, Hitler greets an officer. On the left Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg, on the right Wilhelm Keitel Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1984-079-02 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.Fall of the Third Reich

Meanwhile, the Third Reich disintegrated further. In the East, the Red Army advanced relentlessly. In October 1944 they crossed the border into eastern Prussia. A few months previously, the Allies had broken out of their bridgeheads in Normandy and were steadily advancing towards the borders of the Reich. Between June and September 1944, the Wehrmacht lost a million men dead, captured or missing.

Even when it must have been crystal clear to Keitel as a military man that the Third Reich was at the verge of collapse, his loyalty remained unbroken and he continued to admire Hitler. He kept encouraging his troops to continue the fighting; he even offered a bonus of 500 RM for each arrested deserter. Keitel also ordered the reserves of poison gas to be transferred to Berlin. Goebbels advocated the actual deployment of poison gas. Hitler however did not want to start a chemical war. On February 1945, - suggested by Goebbels – Hitler proposed to denounce the Geneva Convention on occasion of the bombardment on Dresden and to execute tens of thousands American and British prisoners-of-war in reprisal of the attack. The benefit of this plan was, in his opinion, that the counter-measures the Allies subsequently would take against German prisoners-of-war would persuade the soldiers on the western not to desert so quickly. Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, Alfred Jodl, Joachim von Ribbentrop and even Keitel protested vehemently against this proposal, in particular because of the expected Allied counter-measures. Therefore Hitler dropped the idea.

In February 1945, Hitler settled down in the Führerbunker beneath the Reichskanzlei in Berlin. The first military meeting was held in the afternoon every day. The second late in the evening or even at night. These meetings could last for hours. Adolf Hitler, who never could accept that others did not agree with him, now bore no contradiction at all. Except for Heinz Guderian, meanwhile having been promoted to Generalstabschef, there were no critics among his generals and Guderian was sacked on March 18 and replaced by General der Infanterie Hans Krebs. Keitel now had so little authority, junior officers now called him the state errand boy.

On April 15, Hitler named Karl Dönitz his military representative in the north and Albert Kesselring in the south, in case the Third Reich would be cut in half. On April 16, a Russian attack ushered in the battle for Berlin. April 20, Soviet troops reached the outskirts of the city and shelled the town. Like many others in Hitler's entourage, Keitel urged Hitler to leave Berlin and retreat to the Obersalzberg in Bavaria. Hitler replied: "Keitel, I know what I want, I shall continue fighting in Berlin."

On April 22, 1945, Adolf Hitler ordered the III. SS Germanische Korps commanded by SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner, to launch an attack on the 1st Byelorussian Front on its northern flank. Actually, this German Korps did not exist anymore as it had transferred all of its operational units to 9. Armee. The refreshments it did receive consisted of troops from the navy and the Luftwaffe who had no experience whatsoever as infantry soldiers. When it became clear Steiner did not launch an attack, Hitler flew into a rage during the military meeting that afternoon. He ranted he had been betrayed by everyone and that the troops refused to fight. He stated the war was lost and that everyone could leave as far as he was concerned but he would stay in Berlin. Joseph Goebbels managed to calm him down. Alfred Jodl suggested that 12. Armee of General der Panzertruppen Walther Wenck, stationed near the Elbe would make an effort to relieve Berlin. Hitler dispatched Keitel to the headquarters of 12. Armee. The remainder of the Wehrmacht HQ settled down in Krampnitz near Potsdam, the headquarters of the OKH.

About Keitel's arrival at Wenck's HQ on April 23, historian Beevor writes: "He addressed the assembled officers as if it was a Nazi party meeting; swinging his baton he called on them to rescue the Führer." Wenck however did not obey. He knew his 12. Armee, which had only three divisions at its disposal and no tank support, was far too weak to achieve anything against the supremacy of the Red Army. 12. Armee did launch an attack to the east though, its only purpose being to form a corridor through which soldiers of the encircled 9. Armee of General der Infanterie Theodor Busse could escape to the Elbe. The attack was successful, enabling the men to surrender to the Americans rather than to the Soviets.

Meanwhile it began to dawn on many high ranking German generals that the battle for Berlin was lost. They refused to sacrifice soldiers in a senseless battle any longer. Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici ordered the retreat of 3. Panzerarmee commanded by Generaloberst Hasso van Manteuffel. When Keitel learned of this, he became furious and ordered Heinrici to report to OKW headquarters, now located in Dobbin. Wisely enough, Heinrici did not do so, as he would probably be executed and he went into hiding until the end of the war.

In the bunker, a mood of paranoia prevailed. On April 28, General der Infanterie Hans Krebs, Generalstabschef of the OKH contacted Keitel and Jodl from Hitler's bunker in Berlin, urging them to give full priority to the liberation of Berlin. The battle for Berlin was as good as over though. Alfred Jodl refused to commit Steiner's units to battle, despite Keitel's urging. Historian Ian Kershaw writes: "In the bunker there was now a mood in which even lapdog Keitel and always loyal Jodl were suspected of treason because they had failed to relieve Berlin." Next day Hitler asked about the progress of 12. Armee of Walther Wenck. In the early morning of April 30, Keitel reported that not a single attack by Germans was taking place and that the situation was hopeless. A few hours later, Hitler committed suicide.

Following Hitler's death, negotiations about the surrender of the German armed forces were opened. The new Reichspräsident, Karl Dönitz refused unconditional surrender for the time being. He formed a government and maintained Jodl and Keitel in their functions. It is said that Keitel took the same attitude towards Dönitz as he had previously shown towards Hitler. On May 7, 1945, at the headquarters of the Allied supreme commander Dwight Eisenhower, Jodl signed the unconditional surrender of the German armed forces. As the Russian delegate who had signed the agreement in Reims, officially was not authorized to act on behalf of the Supreme Command of the Red Army, It was stipulated there would be a second ceremony at which representatives of all German land, sea and air forces should be present. Joseph V. Stalin suggested this meeting should take place in Berlin.

In the night of May 7 to 8, 1945, Keitel signed the ratification of the agreement reached in Reims, concerning the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht at the headquarters of Georgy K. Zhukov in the Berlin suburb of Karlshorst. Keitel was subsequently ordered to go to Flensburg in order to surrender to the Allies. He departed with 330 lbs of baggage and 2 escorts. Early May, the last meeting of the OKW was held. Keitel would have declared here: "As a prisoner-of-war, I am facing charges as a war criminal. My only wish is that my former subordinates will be spared a similar fate. My military career is over, my life is nearing the end."

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- ratification

- Confirmation, agreement by a government or parliament of an international agreement.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

The so-called Führerbunker in the garden of the destroyed Reichskanzlei 1947. The entry is on the left Source: Wikipedia.

The so-called Führerbunker in the garden of the destroyed Reichskanzlei 1947. The entry is on the left Source: Wikipedia. On May 5, 1945, an agreement between General Foulkes on behalf of the Allies and Generaloberst Blaskowitz on behalf of the German forces is signed in Wageningen, the Netherlands Source: Library and Archives Canada/PA-138588.

On May 5, 1945, an agreement between General Foulkes on behalf of the Allies and Generaloberst Blaskowitz on behalf of the German forces is signed in Wageningen, the Netherlands Source: Library and Archives Canada/PA-138588.Arrest and the Nuremberg Trial

On May 13 the former chief of the OKW was arrested in Flensburg and transferred to Camp Ashcan in Mondorf-les-Bains in Luxemburg. In august he was transferred to the prison in Nuremberg. From May 1945 onwards, Keitel started to write his memoirs, full of self pity but void of any reflection. He stated for instance: "I could have (after he was arrested) ended my life totally unguarded and no one could have stopped me but the idea did not occur to me as I could never have dreamed that such a Via Dolorosa was awaiting me as this tragic end in Nuremberg.

Prison psychologist in Nuremberg, Gustav Gilbert, declared about Keitel he had just as much spine as a jelly fish. "He kept emphasizing he was just a little man with no authority and that he actually acted as Hitler's spokesman." Keitel once pleaded with Gilbert and psychiatrist Douglas Kelly to visit him more often so they could lend moral support.

On October 18, 1945, Keitel and 21 other high ranking Nazis were indicted by the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg for crimes against peace, waging of a war of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The trial officially began on November 20. Keitel was interrogated on April 3, 4 and 5, 1946 by his attorney, Dr. Otto Nelte and on April 6 and 8 by attorneys of the prosecution. The argument he had no power was the nucleus of his defense. All orders originated directly from Hitler and he had no influence. He did accept his responsibility though. He claimed he had opposed many orders from Hitler. He made the conspicuous claim that according to him, Russian prisoners-of-war were treated far better than necessary conform Hitler's instructions. He did not mention the over 3 million Russians who died in German captivity. Keitel admitted he knew of the existence of the concentration camps but he claimed to have known nothing of the deplorable living conditions in the camps. Heinrich Himmler would have invited him for a visit to Dachau but he had declined. Requested by Erich Raeder and Wilhelm Canaris he would have done his best – in vain - to get Pastor Niemöller released. When he was confronted during the trial with motion pictures shot in the concentration camps, he said he felt ashamed because he was a German and had to cry.

In the first weeks of the Trial, Hermann Göring behaved like some capo Mafioso, trying to influence his co-defendants and forbidding them to admit anything or to plead guilty. When Keitel remarked during lunch that the defeat of the Third Reich was due to the mistakes of Adolf Hitler, he was sharply reprimanded by Göring. In order to lessen Göring's influence, the defendants were separated during meals. From then on, Keitel shared a table with Hans Frank, Arthur Seyss-Inquart and Fritz Sauckel.

Jodl and Keitel felt bothered by the military witnesses Friedrich Paulus and Eric von Lahousen as they had violated their oath of allegiance. Asked by his attorney how he would act, should he find himself in a similar position again, Keitel declared he would sooner have opted for death than to get entangled in the web of such wicked measures.

Wilhelm Keitel, who looked like a real Prussian general (tall, blond hair and always well dressed) maintained his military posture during the trial. He sat ramrod straight on the bench without any facial expression. He kept his cell clean with military precision. Goldensohn described Keitel as a formal general yearning for approval. The former Generalfeldmarschall got noticed by standing at attention each time he was spoken to by someone in Allied uniform. During the trial and afterwards as well, the generals tried to draw a line between the regular Wehrmacht soldiers who would have only been engaged in a bitter fight against a merciless enemy and the members of the SS who would have committed all the crimes. Keitel declared openly: " A German soldier never got the idea to kill women and children" This was an evidently incorrect statement. There was ample evidence about numerous mass murders committed by members of the Wehrmacht. Many crimes were also committed based on the Kommissar- and the Kommandobefehl mentioned earlier. Later on, Keitel told prison psychiatrist Kelly that he was ashamed of the crimes committed by the German armed forces.

On August 31, 1946, Keitel made his final statement, along with his co-defendants. His statement consisted mainly of denials of the arguments of the prosecution. He wanted to make clear once again, he had been unable to issue orders and that he had not handed the Wehrmacht over to the Party. In the last words of his statement, he showed a little sense of guilt: "I believed but I erred and I was not in a position to prevent what ought to have been prevented. That is my guilt. It is tragic to have to realize that the best I had to give as a soldier, obedience and loyalty, was exploited for purposes which could not be recognized at the time and I did not see that there is a limit set even for a soldier’s performance of his duty. That is my fate." Keitel would have made an even more explicit confession of guilt but Göring would have forbidden him to do so.

Read the entire Final statement Keitel here.

Keitel's defense did not help him much. Superior orders were neither admitted as valid defense, pursuant to Article 8 of the Charter of the IMT, nor as mitigating circumstance. In its verdict, the Tribunal stated: "Superior orders, even to a soldier, cannot be considered in mitigation where crimes so shocking and extensive have been committed consciously, ruthlessly and without military excuse or justification.

On September 30 and October 1, 1946, the verdicts were read. The Tribunal first dwelt on the guilt of each defendant. Keitel was indicted on four counts:

- Conspiracy to wage a war of aggression or crimes against peace

- Waging of a war of aggression

- War crimes

- Crimes against humanity

"Defendant Wilhelm Keitel, based on the Counts of the Indictment of which you have been found guilty, the Tribunal sentences you to death by hanging."

Keitel asked his attorney to submit a petition for pardon to the Allied Control Council for Germany. His main request was to have his execution carried out by a firing squad. In his request, Keitel declared: ".. my guilt stemmed from a sense of duty which is considered an essential, rightful and fundamental characteristic of a good soldier by all armies the world over." Keitel's request was rejected. He awaited his sentence meekly. He asked the prison physician to hand over his tobacco ration to someone who smoked. He declared death was his only rescue.

In the early morning of October 16, 1946, the verdict was executed. Wilhelm Keitel was the second man, after Minister of Foreign Affairs Joachim von Ribbentrop, who was led to the gallows. His last words were: "I beg the Almighty to have pity on the German people. Over 2 million German soldiers went to their death for the Fatherland. I shall follow my sons, everything for Germany." At that time he was unaware that his son Ernst-Wilhelm was still alive and in Russian custody. He would be released in 1955. Keitel's execution did not proceed without a hitch. As henchman John Woods had not applied the noose properly and the rope was too short, Keitel did not die from a broken neck, the usual cause of death, but from suffocation. His death struggle lasted more than 20 minutes.

Definitielijst

- Ashcan

- Code name for the American detention centre for high-ranking Nazi officers in Mondorf-les-Bains in Luxembourg.

- crimes against humanity

- Term that was introduced during the Nuremburg Trials. Crimes against humanity are inhuman treatment against civilian population and persecution on the basis of race or political or religious beliefs.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Dedicated National Socialist

Keitel's role remains somewhat ambivalent. German historian Werner Maser describes Keitel as a military secretary who showed unconditional loyalty towards the Führer but hardly possessed any power.

During his examination at the Trial, witness Bernd Gisevius testifed however:

"Keitel held one of the most influential positions in the Third Reich. It may well be Keitel did not influence Hitler in large measure but I must testify here and now that Keitel had a far stronger influence on the OKW and the Wehrmacht. Keitel decided which documents were to be presented to the Führer. It was impossible for Admiral Wilhelm Canaris or one of the other gentlemen I mentioned, to submit an urgent report to Hitler on his own initiative. Keitel took over and he did not pass on anything he did not like or he officially ordered these gentlemen to abstain from drafting similar reports. Keitel frequently threatened these men as well. He told them they were to limit themselves exclusively to their own spheres of interest and that he could not protect them in regard to any political statement critical of the Party and the Gestapo, the persecution of the Jews, the murders in Russia or the campaign against the Churches and, as he said later, he would not hesitate to dishonorably discharge these gentlemen from the Wehrmacht and hand them over to the Gestapo."

Albert Speer confirmed the words of the former officer of the Abwehr. In the biography by Gitta Sereny, he remarks: "Those three (Bormann, Lammers and Keitel) finally managed to form a cordon around Hitler ….. all military could only talk to Hitler through Keitel."

Everything points to this: Keitel was a Nazi general. He had little direct influence on Hitler himself but as he arranged which military leader could speak to Hitler and which documents were submitted to him, he was far from powerless. His role entailed more than that of a secretary. Although Keitel did not consciously make the Wehrmacht subordinate to the Führer – that was the dictator's own decision – he did little or nothing however to limit Hitler's influence, what's more, he even enlarged it. Whatever he may have claimed, Keitel protested only very rarely against the criminal orders of Hitler and even then, his protests were weak. Alfred Jodl is known to have discussed orders with Hitler, managing to play down a few of them, among other things by temporizing them. Keitel on the other hand is not known for any serious opposition against Hitler, on the contrary: he added disgusting comments to many of Hitler's orders such as: In the East, a life is worthless." Admittedly, even if had he protested vehemently, it propably would not have made much difference as the orders would have been issued anyway. Keitel was a typical product of his own upbringing. Obedience was a sterling virtue for him. His attitude towards Hitler was subservient to the point where it even earned him the derision of his colleagues.

His words after the war are examples of self pity: "I had no power and how could I have known of crimes?" Without him, war crimes would have been committed anyway but he did nothing against Hitler's criminal orders and was a willing executor of Nazi aggression and murderousness.

Read also: Verdict Keitel, Hearing Keitel 1, Hearing Keitel 2, Hearing Keitel 3, Hearing Keitel 4, Hearing Keitel 5

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Jews