Introduction

As early the summer of 1943, one thing was certain for the soldiers of the Red Army: they would end the war in Berlin at all costs. The conquest of the German capital was considered a well-deserved prize, as the fitting final phase of an unprecedented brutal and bloody war.

The world famous picture by Yevgeny Khaldei of the Red Banner on the Reichstag, taken on May 2, 1945. The flag had already been raised on April 30, but that monent was not recorded on film. Source: Public Domain

At this last stage of the war, the Red Army had tremendous numerical and technological superiority, but extremely large losses were suffered on both the German and Soviet sides. The Germans fought with the courage of desperation to postpone the inevitable final defeat for as long as possible, while the Soviet commanders - competing for the honor of hoisting the Soviet flag on the Reichstag - did everything they could to reach the city center as quickly as possible. Although only one result was conceivable, both parties fought extremely fiercely and cruelly. Relief attempts by imposing armed forces 'on paper', conceived in the fantasy world of the Führerbunker, ended in nothing. The Battle of Berlin was one of the last major battles in the war against Germany; six days after the weapons fell silent in Berlin, the Third Reich capitulated and World War II in Europe was over.

Definitielijst

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Soviet plan and preparations

Although agreements had already been made between the Americans, British and Soviets during the war about the post-war partition of Germany, the conquest of Germany was not coordinated. At the Yalta Conference (February 4-11, 1945) it was decided that after the war Berlin would be divided into four occupation zones, but who would have the honor of taking the capital of the Third Reich was uncertain for a long time. After the Normandy landings, the Anglo-American armies were only 99 miles further away from Berlin than the spearheads of the Red Army near Vitebsk, which would soon launch Operation Bagration there. Since the Soviet Union had by far the largest army of all Allied countries, had fought uninterrupted battles with the Axis powers since June 1941, and had suffered by far the heaviest losses during the war, Joseph V. Stalin believed that the Red Army deserved to take Berlin.

Stalin thought there was a chance that the Germans would give up the struggle in the West and deploy the entire armed forces in the war against communism. The Germans had indeed strewn propaganda magazines over the Allied armies in the West, calling on them to join forces with the German army to fight the communists. Stalin was very suspicious of Winston Churchill in particular and considered him able to conclude such an agreement with the Germans - contrary to the agreements made in Yalta. This was an error of judgment by Stalin, but because the advance of the Western Allies had started to gain momentum in the early months of 1945, Stalin wanted to speed up the offensive towards Berlin.

The advance to the Oder

As early as the summer of 1944, the Red Army had reached the Weichsel in eastern Poland, and after a long supply period, the Weichsel-Oder offensive finally began on January 12, 1945. The attack came as a surprise to the Germans, and the numerically superior Soviet armies quickly advanced. The enormous force of the Soviet troops also played a role here: the four jaded armies that the Germans deployed (2. , 9. and 17. Armee and the 4. -Panzerarmee) were quickly overrun. Marshal Ivan S. Konev's 1st Ukrainian Front kicked off the campaign on January 12 and was deep in Silesia two weeks later. The 1st Byelorussian Front of Marshal Georgy K. Zhukov, immediately north of Konev, attacked on January 14 near Warsaw and stood on the banks of the Oder on January 29, only 50 miles from Berlin.

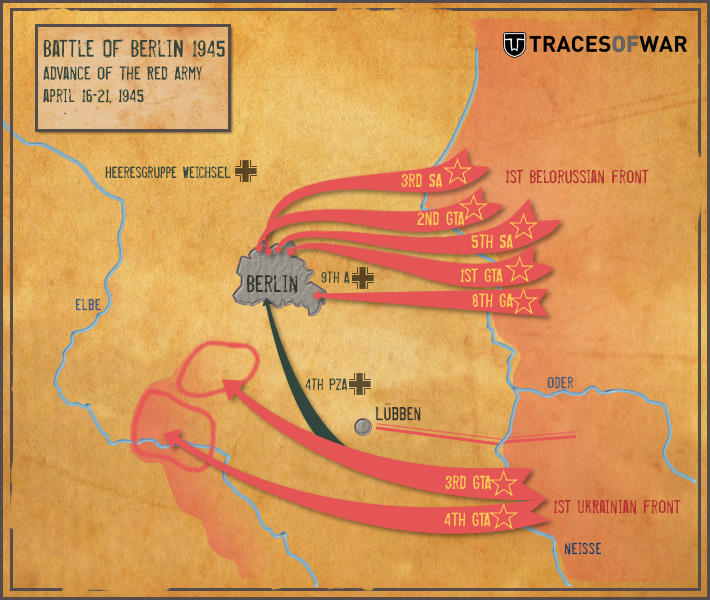

Advance of the Red Army, April 16 to 21 1945.PZA: Panzerarmee, STL: Shock troops, GTL: Guards Tank Army, GL: Guards Army. Source: Roger Paulissen, TracesOfWar

Stalin now faced a dilemma. Berlin was within reach, but the rapid advance had led to a concentration of German forces around Königsberg in early February, Heeresgruppe Weichsel still standing in Pomerania and the fortified cities of Breslau, Posen and Küstrin not yet conquered. Colonel General Vasily I. Chuikov, commander of the 8th Guards Army, urged Zhukov to advance to Berlin and clean up the rear of the resistance later on. The question is whether the Berlin defenders could have stopped an attack in February.

However, Stalin chose to eliminate the various German threats before targeting Berlin. Konev therefore surrounded Breslau and found connection to Zhukov's front on the Oder, Zhukov's 1st and 2nd Guards Tank army turned to the Northwest to push back together with Marshal Konstantin K. Rokossovsky's 2nd Byelorussian Front and Chuikov's 8th Guards Army conquered the fortified towns of Posen and Küstrin. Rokossovsky's 2nd Byelorussian Front was now also on the Oder, three Soviet fronts with a total of 34 armies were ready for the attack on Berlin.

From the Oder to Berlin: Zhukov vs. Konev

By November 1944, the General Staff had broadly drawn up a plan for the attack on Berlin, but in early March 1945, Zhukov came to Moscow to work out the details of the plan with the chief of the General Staff, Army General Aleksei I. Antonov. On March 8, the plan was approved by Stalin, after which the final logistical preparations for the offensive were completed. On April 1, Zhukov and Konev were summoned to Moscow, where the operation plan was explained and the starting date was set on April 16.

The plan was relatively simple: Zhukov had to launch a frontal attack towards Berlin from the bridgeheads on the Oder via the Seelower Heights. On Zhukov's northern flank Rokossovsky had to go around Berlin and launch an attack from the west. South of Zhukov, Konev would advance towards Dresden and Leipzig and then turn towards Potsdam, completing the encirclement. Zhukov considered it his privilege to be first in the center of Berlin and hoist the Soviet flag on the Reichstag building, but Konev objected.

Both Zhukov and Konev were unwilling to let the other run off with this honor. An important reason for this lay in the rivalry between the two marshals, which went back many years: as early as 1939 during the fighting against the Japanese at Khalkhin-Gol, the seed for the animosity between the two officers was sown. Both were known to be extremely self-righteous. Zhukov also disliked the political corps within the army, from which Konev came. Zhukov took credit for Khalkhin-Gol's successes and was named a 'Hero of the Soviet Union', while Konev, at the time even higher in rank, got nothing from it.

There are indications that Stalin, who had a knack for assessing and exploiting human weaknesses, had been aware of Konev's envy since 1941 and began preparing him as rival for Zhukov. Stalin refused to allow his officers to grow above himself and he could play off Konev nicely against the ambitious Zhukov. In October 1941, Zhukov succeeded Konev as commander of the Western Front, which had lost nearly four armies under Konev in a major encirclement. Zhukov kept Konev as his deputy, but Konev held this position for no longer than a week. In 1943 and 1944, Zhukov, now a Marshal, commanded two or three fronts simultaneously during several operations, one of which was under the command of Konev. Due to the narrowing front line, from November 1944, Zhukov had to settle for command of a single front, the 1st Byelorussian, effectively putting him on an equal footing with Konev, who now also held the rank of Marshal.

The memories of the two marshals of the discussion of April 1, 1945 are very different. Zhukov later stated that Stalin had promised him Berlin and that Stalin had ordered Konev to enter the southern suburbs of Berlin only if Zhukov's offensive stalled. Konev remembered none of this. He later claimed that Stalin and the General Staff, at his insistence, had drawn the line of demarcation between the two fronts no further than Lübben (southeast of Berlin), implying that Konev should also aim his arrows at Berlin, if conditions permit. "Kto pervy vorvyotsya, to pust i beryot Berlin", Stalin is said to have said - "Whoever breaks through first, may also take Berlin".

The Seelower Heights

Zhukov had a strong force on the bridgeheads on the Oder. His front alone had nearly 14,600 cannons, over 1,500 Katyusha rocket launchers, and nearly 3,100 tanks and units of self-propelled guns. The main barrier he would encounter on the route to Berlin were the Seelower Heights, a series of steep hills that encircled the village of Seelow and protruded 196 feet above the low-lying banks of the Oder. Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici's Heeresgruppe Weichsel, in particular the 9. Armee of General der Infanterie Theodor Busse, had positioned artillery on the hills to cover the entire approach area. Zhukov planned to launch a night attack, in which 143 searchlights would blind the defenders. The original attack plan had foreseen a flank attack by Zhukov's two tank armies (1st Guards Tank Army under General Mikhail Y. Katukov and 2nd Guards Tank Army under General Semyon I. Bogdanov), but concerned about the German artillery threat, Zhukov chose to direct his tanks to storm the hills, in the wake of Chuikov's 8th Guards Army.

Just before dawn on April 16 - the Western Allies were now barely 81 miles from Berlin - Marshal Zhukov signaled the start of the attack at Chuikov's headquarters. The enormous artillery and air bombardment that heralded the offensive was felt in Berlin. After half an hour the spotlights were turned on, but due to the dense smoke, there was nothing to see. More than anything, the reflections from the searchlights hindered the advancing Soviet infantry. The Oderbruch was partly soggy and partly sandy, and the accessibility was made even more difficult by the numerous bomb craters, as a result of which the vehicles and cannons quickly got stuck. In addition, Heinrici was aware of the Soviet plan and had the front line cleared, causing the bombing to hit mostly empty bunkers and trenches.

Chuikov's vehicles got stuck on the steep slopes of the heights. Zhukov then made the notable mistake of sending his two Guard Tank Armies forward in an attempt to capture the hills quickly. Supply roads quickly became clogged and the two guard tank armies, which were normally active on open ground, now barely had any freedom of movement. The crews of Busse's 900 guns on the hills were nervous and moderately trained, but the barely mobile Soviet tanks were sitting ducks for the German anti-tank guns and suffered heavy casualties.

On day two of the operation, the heights were stormed, but most defenders retreated to the third line of defense. On the third day, Chuikov broke through this line, but suffered heavy enemy fire and some counter attacks. On the 19th, Zhukov's main force reached Müncheberg and Bogdanov's 2nd Guards Tank Army was 12. 5 miles north past Wriezen. Zhukov had regained momentum, and by the 20th, his vanguard had reached the outskirts of Berlin.

The result of four days of fighting

Konev had achieved success much faster in the south. He had chosen darkness and crossed the Neisse on April 16, covered by dense smoke screens. The 4. Panzerarmee of General der Panzertruppe Fritz-Hubert Gräser on the left flank of Heeresgruppe Mitte (under Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner) was quickly pushed back. On April 17, Konev's troops had crossed the Spree, and on April 18, his front had already covered 37 miles. Stalin rebuked Zhukov for the wrongful deployment of his tank armies and rewarded Konev by allowing him to advance to Berlin. Konev's two Guards Tank Armies (the 3rd Guards Tank Army under General Pavel S. Rybalko and the 4th Guards Tank Army under General Dmitry D. Lelyushenko) made significant progress in the days that followed and reached Berlin on April 21.

The Red Army paid a heavy toll for the breakthrough at Seelow: by their own admission more than 33,000 soldiers had died (the actual number could well have been double) and 743 tanks and some units of self-propelled guns were lost, the equivalent of a full tank army. It didn't seem to bother Zhukov. Speaking at a press conference in June 1945 in honor of the victory, he said casually about the fighting at Seelow: "It was an interesting and instructive fight, especially in terms of the pace and technique of night fighting on such a scale". On German side about 12,000 men from the 9. Armee died, and the rest of the army was located south of Müncheberg, between Zhukov and Konev and isolated from the rest of Heeresgruppe Weichsel.

Definitielijst

- communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Reichstag building

- German government building in Berlin.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

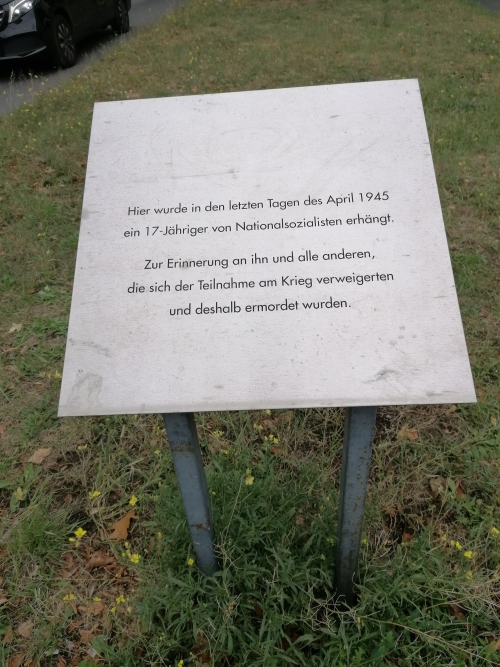

German defense

Berlin had already endured hundreds of bombings during the war: by American B-17s during the day and British Lancasters at night. A significant portion of the total 328 square miles of urban area had been destroyed, but the government and Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) were still located in the city. On January 15, Adolf Hitler had left the Adlerhorst near Frankfurt and moved into his office in the Reichskanzlei the following day. From mid-February, Berlin endured air bombardments virtually every day and night. 78 percent of the city center was destroyed and 48 percent of the Tiergarten district. The Reichskanzlei was also repeatedly hit and from the beginning of March Hitler lived and worked in the Führerbunker beneath the garden of the Reichskanzlei

Berlin prepares for war

Out of the 4.3 million inhabitants before the war, Berlin had 2 to 2. 5 million inhabitants left in April 1945 (including refugees from the east). The population was severely affected by the Allied bombings: a third of the bombing tonnage on Berlin fell from February to May 1945, during which an estimated 110,000 civilians were killed. However, life went on for the survivors, and the people of Berlin prepared as best as they could under the circumstances for the upcoming fighting. People stocked up on food supplies, the capacity of hospitals was expanded, and bomb shelters were built.

From a military point of view, the defense of Berlin was prepared late. Hitler refused to give permission for political and psychological reasons, but probably also because of his growing unworldliness. As long as he imagined that he still had strategic choices, he refused to pay attention to the Berlin sector. The evacuation of the civilian population has also not yet been discussed. It was Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the OKW, who decided in early February to have the army make preparations.

The Berlin garrison

Responsibility for the defense shifted to Wehrkreis III, the military district that oversaw Berlin, Brandenburg and part of Neumark (western Poland). Joseph Goebbels, in addition to his position as Propaganda Minister, as Reichsverteidigungskommissar Wehrkreis III was ultimately responsible for the defense of Berlin. The commander of Wehrkreis III, Generalleutnant Bruno Ritter von Hauenschild, therefore had to ask Goebbels for approval of defense plans. Goebbels refused to approve an evacuation of the civilian population, which he said would cause unnecessary panic, but he also made no preparations for the food and care of the civilian population in case the city turned into a battlefield. Like Hitler, Goebbels had a flawed sense of reality, issued numerous contradictory orders, and meddled in defense matters at all levels, but showed genuine interest in defense and consulted commanders in the field.

Generalleutnant Reymann inspecting a machine gun nest in Sector B, March 1945. Source: Bundesarchiv.

Von Hauenschild was replaced due to illness on March 6 by Generalleutnant Hellmuth Reymann. He deemed the dual function of commander of Wehrkreis III and of Verteidigungsbereich Berlin unworkable, and at his request retained responsibility for the defense of Berlin only. Hitler declared Berlin a fortress in early February and promised Reymann that in due course he would have front troops at his disposal to man the defensive positions. In the second half of March, Reymann had only a handful of troops: the Wachregiment "Großdeutschland", a Territorial Battalion, an SS Territorial Police Battalion, a company of buried tanks, an anti-tank company, two small engineering battalions, a pair of battery-looted cannons manned by Hitler Youth members and 20 Volkssturm battalions.

The Volkssturm formed a special category. The organization was created in the fall of 1944 to serve as a local people's militia and to construct defenses. Summoning Volkssturm members was the task of the Gauleiter, who also commanded the units. In Berlin, this was one of Joseph Goebbels' many duties. Since almost all German men between the ages of 17 and 45 were already under arms, the Volkssturm consisted mainly of teenagers and old men who were capable of handling a weapon but were not fit enough for active military service. The Wehrmacht was not concerned with the armament, equipment and clothing of the Volkssturm ; it had to acquire this locally and therefore had shortages everywhere.

A member of the Berlin Volkssturm of advanced age is trained to use a Panzerfaust. Source: Bundesarchiv

In addition to the Volkssturm, boys from the Hitlerjugend were also deployed as soldiers. The Hitler Youth initially consisted of children between the ages of 14 and 18, but in 1945 12-year-olds also joined. In March, everyone born in 1929 or later - including 15 and 16-year-olds - got their hands on a weapon, but even younger children sometimes fought. The fanaticism they often fought with shocked the Soviet soldiers as much as the indifference of the Hitler Youth leaders.

In addition, the 1. Flak-Division of Generalmajor Otto Sydow was stationed in Berlin, which Reymann would have at his disposal when the fighting started. Sydow's division managed anti-aircraft batteries in Berlin; his division had been stripped bare to fortify the Oderfront, and of the original 500 batteries, few remained. However, the remaining positions were well positioned and relatively well armed. The main anti-aircraft installations were the three Berlin Flak towers, built in Friedrichshain Park, Humboldthain Park and in the Zoo, immediately southwest of the Großer Tiergarten. These huge concrete behemoths were lavishly equipped with anti-aircraft guns and were able to protect civilians during bombing raids. Each Flak tower consisted of a turret, armed with four double-barreled 12. 8 cm guns and twelve quadruple 2 or 3. 7 cm guns, and a fire control tower. The turrets contain barracks for the 100-man garrison, a hospital, an art store, a radio room, field kitchens and a canteen. Almost 15,000 civilians could be accommodated in the basement. The towers were initially assigned an air defense role, but during the Battle of Berlin they would act very effectively against ground targets.

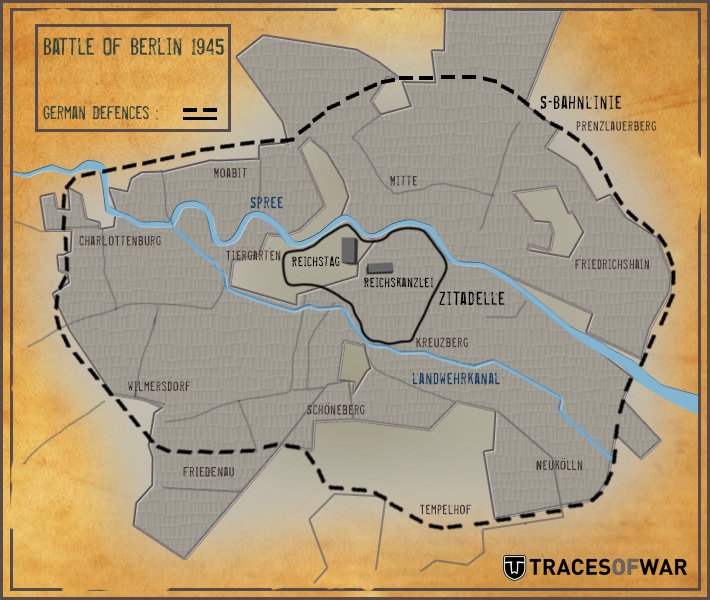

Defenses

Only in March did Reymann develop a defense plan, which provided for four lines of defense. The fourth and outer was the Äußerer Sperr-Ring, which enclosed Berlin and all its suburbs and had an average radius of about 19.8 miles. The eastern boundary of this line ran from Biesenthal, Tiefensee and Rüdersdorf to Königs Wusterhausen on the Berliner Ring. The third defense ring was the "Grüne" Hauptkampflinie, a perimeter roughly 10 miles from the city center. This ring ran roughly around the districts of Tegel, Pankow, Marchow, Marzahn, Dahlwitz, Rahnsdorf and Rudow. The second line was the Hauptkampflinie S-Bahnring, which followed the S-Bahn around the districts of Charlottenburg, Moabit, Wedding, Prenzlauer Berg, Friedrichshain, Neukölln and Schöneberg. Finally, the inner defense ring, surrounding the Zitadelle, enclosed the government district, including the Führerbunker, Reichskanzlei and the Reichstag. The entire area with all four lines of defense was divided into eight 'pie slices' called 'Befehlsabschnitte'. These defense sectors were designated A to H (clockwise from the Northeast). The Zitadelle in the center formed its own sector, Abschnitt Z. Only when the code word 'Clausewitz' was given, the warning that the enemy was approaching, would the sector commanders - most of whom were in the rank of Oberstleutnant or Oberst - be given command of all Wehrmacht troops and Volkssturm units that happened to be in their sectors at the time.

The two-month wait for the Red Army's final offensive gave Reymann time to prepare a significant number of defenses. In the weeks leading up to the fighting in Berlin, 70,000 people were deployed daily, in addition to Reymann's engineering units, to construct defenses, bunkers, tank obstacles and barbed wire barriers, deploy explosives and mines. Personnel was provided by the Organization Todt and the Reichsarbeitsdienst, which usually had adequate tools. In addition, soldiers, civilians, prisoners of war and forced laborers were deployed. The factories that had not yet been destroyed in the city remained operational to the last minute and produced supplies for the lines of defense day and night, but it was not enough to supply all lines adequately. The transport of construction crews proved even more problematic: there was an acute shortage of fuel and the countless air strikes caused parts of the railway line to be continuously out of order.

In a general sense, efforts were made to barricade all major intersections and to transform all solid buildings into fortified positions, which was largely successful. However, as the periphery of the city was reached, the defenses were less well armed and less effective. The "Grüne" Hauptkampflinie consisted of little more than a trench, supported by a number of covered scaffolding and a few obsolete buried tanks. A tank ditch ran in the southeast. The Hauptkampflinie S-Bahnring was considerably stronger and consisted of parallel trenches, ramparts and tank ditches. The defenders were able to hide in buildings within the perimeter and their range was excellent. The Zitadelle in the heart of the city, where the defenses partly followed the course of the Spree and the Landwehrkanal, contained the best-equipped line of defense. All streets were barricaded, and machine guns were set up in basements and on higher floors. Partition walls had been broken through so that the defenders could reach the different cellars from the inside. The U-Bahn was also barricaded at intervals. Cannons and tanks - including several Tigers - were dug in and trenches were constructed in the Tiergarten. Strong bastions were constructed immediately east and west of the Zitadelle, on Alexanderplatz and the Knie (Ernst-Reuter-Platz).

On April 15, Reymann attended a meeting at the headquarters of Heeresgruppe Weichsel, covering among others the 483 bridges and many important facilities in Berlin. Hitler had decided on a scorched earth policy and Reymann had placed hundreds of explosives in the city. Both Generaloberst Heinrici and Albert Speer, the Minister of Armaments, who was also present, tried to persuade Reymann not to implement this policy in order to prevent famine and the economic collapse of the capital. Blowing up the bridges would mean that gas, water, sewer and electricity lines would no longer work. Moreover, Heinrici had no intention of having his Heeresgruppe fight in Berlin itself; he wanted to hold out on the Oder for as long as possible and then retreat on both sides of the city. He advised Reymann to take positions only at the city limits and to save the city itself from the violence of war.

Map of the major districts, locations and roads in Berlin and the two inner defense perimeters. Source: Roger Paulissen, TracesOfWar

Much hope was put in the line on the Oder, but the German war industry and the number of available troops were insufficient to build a strong defense. In the sector immediately east of Berlin, only 9. Armee of Theodor Busse with its 14 divisions were deployed. Zhukov's 1st Byelorussian Front was able to deploy more than 90 divisions and more than 50 brigades. Heinrici predicted that he could hold the Seelower Heights for no more than three or four days without reinforcements. These did not come and it was inevitable that the Soviet armies, despite their heavy losses, had already passed the Seelower Heights after three days and reached Berlin on the 20th.

Definitielijst

- Abschnitt

- Description for a district of the Sturmabteilung (SA) or the Schutzstaffel (SS).

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Organization Todt

- A civil and military engineering group. During World War 2 this organisation built the Atlantikwall amongst other things and maintained and repaired connections that were damaged during bombing. In the occupied territories the organisation was notorious for using forced labourers.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Battle in the suburbs

On the morning of April 20, Konstantin K. Rokossovsky's 2nd Byelorussian Front was the last of the three Soviet fronts to begin his offensive from the Oder bridgeheads. The only German army that could resist this sector was Heinrici's 3. Panzerarmee under General der Panzertruppe Hasso von Manteuffel. That same day, Hitler decided late to place Reymann's Verteidigungsbereich Berlin under the command of Heeresgruppe Weichsel, so preventing 3. Panzerarmee from being cut off from the rest of the army group by Rokossovsky's troops, Heinrici decided to have Von Manteuffel`s reserves, consisting of the III. SS-Panzerkorps of SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner, cover Von Manteuffel's southern flank.

To the south, the remains of Busse's 9. Armee, which had been ordered by Hitler to hold its position on the Oder, were surrounded by Zhukov and Konev. The only formation Heinrici could deploy to defend Berlin was one of Busse's corps, the LVI. Panzer Corps of General der Artillerie Helmuth Weidling, which occupied a wide front between the 3. Panzerarmee and Busse's main force. It managed to slow the Soviet troops somewhat on the outer defense line, but soon Bogdanov's 2nd Guards Tank army in the north broke through Weidling's line. A day later there contact with the rest of the 9. Armee in the south was also broken.

Hitler and the Führerbunker

In the damp and noisy Führerbunker, where day and night were indistinguishable, Adolf Hitler slowly but surely lost contact with reality. Apart from a visit to the 51. Armeekorps on March 3, Hitler had not left the bunker since he had moved in. The horrors of war completely passed him by and the orders he issued testified to a completely lacking sense of reality. On April 20, his 56th birthday, Hitler received visits from many notables, including Joseph Goebbels, Karl Dönitz, Albert Speer, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hermann Göring, Arthur Axmann, Martin Bormann and Heinrich Himmler. Given the hopeless military situation around Berlin, most tried to convince Hitler to leave the city soon; the Berghof in the Bavarian Alps was already prepared for his arrival. Hitler rejected this plan, however. Since the Red Army would likely make contact with the Americans and British in central Germany soon, splitting Germany in two, he repeated his earlier instructions that after the split, Dönitz should take command in the north and Albert Kesselring in the south. Hitler's birthday was also a final farewell to some of his senior guests, many of whom left Berlin at the end of the day to move into their new headquarters.

The Soviet artillery had already targeted neighborhoods of Berlin since April 19, but the first shells exploded in the city center on the morning of the 21st. Hitler could feel the explosions in the Führerbunker. He believed that it was railway artillery and that the Soviets must have built a bridge over the Oder. He called General der Flieger Karl Koller, the chief of staff of the Luftwaffe, who then contacted the Flak tower in the Zoo. He reported that these were heavy howitzers which fired from the Marzahn district, directly behind the "Grüne" Hauptkampflinie, about 10 miles from the center.

In an unrealistic attempt to halt the rapid Soviet advance, Hitler decided that afternoon to withdraw Weidling's corps to Berlin. Communication with the corps was poor and Hitler did not know that the corps was already fighting on the city boundary. Weidling also had to seek connections with Steiner in the north. Steiner in turn had to launch a southward attack from Eberswalde. His unit had to be strengthened with everything Heinrici could find and was renamed Armeeabteilung Steiner. Busse's 9. Armee should attack northward from the Spreewald at the same time to encircle Zhukov's vanguard. Both Steiner and Busse, however, were already engaged in fierce defensive battles and with the insignificant reinforcements unable to launch an offensive. Steiner was under such severe pressure from Zhukov's northern flank and his air support that he was forced to evacuate his headquarters in Oranienburg. Busse was in an even more painful situation; tens of thousands of refugees from the eastern provinces had joined his army, and while sufficient food was available, the pocket had to endure continuous air strikes by the 2nd, 16th and 18th air forces. There was a great shortage of fuel and the artillery ammunition ran out on the 21st, after which Heinrici advised Busse to disengage from the Soviet troops, ignore Hitler's orders and withdraw from the Oder.

Although the regular telephone network was still working, communication between units became increasingly problematic from 21 April and the chaos in the German chain of command grew rapidly. Weidling controlled an area between Neuenhagen and Rahnsdorf and had his own command post in Kaulsdorf, not far behind. Nevertheless, there was a rumor that his corps was starting to withdraw to Döberitz, west of Berlin, on which both Hitler and Busse ordered Weidling to be arrested and executed. Meanwhile, Weidling himself had insubordination problems with SS Brigadeführer Joachim Ziegler, the commander of the SS-Panzergrenadierdivision "Nordland", previously attached to Felix Steiners III. SS-Panzerkorps who now felt irritated to fight under a Wehrmacht general. Ziegler decided to join Steiner, after which Weidling relieved him of his command, but then Ziegler was subsequently ordered to return to Berlin with his division, without Weidling.

Relief of Berlin

In the afternoon of April 22, the situation discussion in the Führerbunker was held only by Hitler, Martin Bormann (Hitler's personal secretary), Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel (Chief of the OKW), Generaloberst Alfred Jodl (Chief of Operations of the OKW) and General der Infanterie Hans Krebs (Chief of Staff of the Wehrmacht). When Hitler learned that Steiner had not launched an attack, he flew into a rage. He raved that he had been betrayed by his generals and that their betrayal, ignorance and cowardice had undermined his efforts for Germany. After some time, Hitler recovered and declared that he would stay in Berlin until the bitter end. He also decided to take charge of the defense of Berlin (again). Hellmuth Reymann was then ordered to take command of the Potsdam garrison. His formation received the impressive designation Armeegruppe Spree, but consisted of only two weak infantry divisions.

That evening, Keitel and Jodl learned from Hitler that if Berlin fell into Soviet hands, he would commit suicide. Nevertheless, Hitler continued to look for a military way out. US troops had now reached the Elbe, but clearly had no intention of crossing the river. That's why Hitler decided to order 12. Armee under General der Panzertruppe Walther Wenck to turn east from the Elbe and join Busse's 9. Armee. After this, the two armies had to relieve Berlin together.

Of Wenck's army, only the XX. Armeekorps was of reasonable strength. The XXXIX and XXXXI. Panzerkorps had suffered heavy losses and the XXXXVIII Panzerkorps consisted of a largely immobile Flak division and a variety of smaller units. Wenck informed Keitel he was not ready for his advance until April 25, but Keitel did not pass this on to the Führer. During the situation discussion on April 23, Krebs told Hitler, against his better judgment, that Wenck's army was already on the way. These kinds of incidents clearly illustrate how Hitler continued to live in his fantasy world and how the staff officers who still had a realistic view of the military situation made no effort to disprove falsehoods.

Definitielijst

- Armeegruppe

- Usually consisted of two or three neighbouring Armees, sometimes German and Axis-allied Armees. One Armee HQ, usually the German, temporarily became the commanding HQ of the other Armees. An Armeegruppe would always be subject to a Heeresgruppe. Later in the war the size of an Armeegruppe or Panzergruppe varied significantly. From 1943 onwards an Armeegruppe could be the size of an Armee or just the size of a corps.

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Advance to the S-Bahn

To the north, Armeeabteilung Steiner still defended a line along the Havel, between Oranienburg and Berlin. On the night of April 22-23, the 47th Army managed to cross the Havel at Hennigsdorf. After this, the 47th Army quickly penetrated into the German rear guard. It turned south and soon reached Döberitz and Spandau. The OKW headquarters in Krampnitz, just north of Potsdam, was surprised by the news of cavalry units in the countryside near Döberitz and was quickly evacuated. At the same time, Lelyushenko's 4th Guards Tank Army had penetrated the lake area west of Potsdam. On the morning of April 25, the 4th Guards Tank Army northwest of Potsdam contacted the 47th Army, which surrounded Berlin.

Strength of the garrison

In the eastern suburbs, like Heinrici, Helmuth Weidling had no intention of getting involved in city fighting. On the 23rd he received instructions from Busse to reconnect with the main force of the 9. Armee, an order that Weidling was only too happy to obey. At the same time, he learned of his arrest warrant, after which he contacted Krebs for a statement. Weidling was ordered to report to the Führerbunker early in the evening of April 23. Here he first spoke with Hans Krebs and General der Infanterie Wilhelm Burgdorf, the chief adjutant of the OKW and then also with Hitler. Weidling was told to ignore Busse's orders and that his corps was needed in Berlin. He was to command defenses A to E (northeast to southwest). On the morning of the 24th Weidling was summoned again to the Führerbunker; Krebs told him that the Führer was so impressed by his speech the night before that he had been appointed the new commander of Verteidigungsbereich Berlin. Weidling reportedly said that he preferred to be executed instead of this 'promotion'. Weidling asked Krebs to allow him to act independently, but this request was rejected. His responsibility was to Hitler.

At this stage, Weidling`s LVI. Panzer Corps had the following units at its disposal:

- Panzerdivision "Müncheberg", Generalmajor der Reserve Werner Mummert lost around a third of his troops during the fighting in the suburbs.

- 18. Panzergrenadierdivision, Generalmajor Josef Rauch was still largely intact.

- 20. Panzergrenadierdivision, Generalmajor Georg Scholze had suffered heavy losses.

- 11. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision "Nordland", SS-Brigadeführer Joachim Ziegler was still relatively strong.

- 9. Fallschirmjägerdivision, Oberst Harry Herrmann suffered quite heavy losses.

In total, Weidling's corps currently numbered about 13,000 to15,000 troops. In addition, the Berlin-based units of the 1. SS-Panzerdivision "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler", led by SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke and renamed Kampfgruppe Mohnke, had about 2000 men and there was still 1. Flakdivision of Generalmajor Otto Sydow. Together with all the smaller units, the garrison counted between 45 and 60,000 troops with 50 to 60 tanks, apart from the Volkssturm and Hitlerjugend soldiers. On April 24, the last reinforcements that could still use the corridor in the west arrived, 350 mainly French volunteers of the disbanded 33. Waffen SS-Grenadierdivision "Charlemagne". They were led by SS-Brigadeführer dr. Gustav Krukenberg. Due to the persistent insubordination problems with Ziegler of the Nordland division, Weidling had asked the OKW for a replacement and Krukenberg was chosen.

German strategy

Weidling decided to have his staff headed by two officers: Oberst Theodor von Dufving, Chief of Staff of the LVI. Panzerkorps, became responsible for all military matters, and Oberst Hans Refior, who had previously been Reymann's chief of staff, became liaison officer to the civilian authorities. Weidling's limited freedom of action, as well as the interference of Goebbels and other party leaders, did not benefit the defense. In addition, the chain of command was very chaotic at this stage, both vertically in the military hierarchy and horizontally, and there was often poor cooperation between Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht commanders. The streets were no longer cleared of debris and were continuously under artillery fire, which greatly hindered the work of couriers. The sector commanders were therefore forced to decide for themselves where they would use their very limited resources and which lines they would defend. Reymann's original defense plan simply could not be fully implemented due to a lack of troops. Some commanders held the outer perimeter for as long as possible, others focused primarily on defending tactically located fortified buildings, and still others soon fell back on the S-Bahn line.

To counteract weaknesses in the defense zones, Volkssturm and Hitlerjugend units were mixed with regular army units as much as possible. At the same time, Weidling wanted to keep as many military units intact as possible in order to deploy them as effectively as possible in crucial sectors. The result was that the Soviet troops regularly succeeded in identifying the weaknesses in the German lines and moving around the stronger units.

Soviet strategy

When the street fighting started, the Red Army also thought about the strategy to follow. Previous street battles had shown that infantry units were best split up into small, effective attack groups. Artillery and tank units were split up and assigned a supporting role. A standard group consisted of a platoon of infantry, one or two tanks, a pair of engineers, a pair of flamethrowers, an anti-tank gun section, and two or three field guns. The system worked reasonably well, but the mixing of several armies - Chuikov's 8th Guards Army and Katukov's 1st Guards Tank Army operating in the same sector in the southeast - sometimes created messy situations. The fact that the tank troops now had a supporting role and that Katukov was now subordinate to Chuikov did not go down well with the tank troops.

Army and front artillery meanwhile continued to bombard the urban area. Heavy howitzers were also sometimes assigned to the attack groups and literally shot their way through the barricades and heaps of debris. Particularly in the eastern sector of Colonel General Nikolai E. Berzarin's 5th Shock Troops, buildings were systematically destroyed by cannons and mortars trying to make their way through the center. With 2000 wagons full of ammunition for the calibers above 80 mm, Berzarin had an abundance of ammunition. Also Colonel General Vasily I. Kuznetsov's 3rd Shock Troops simply shot one building after another to rubble. Howitzers and Katyusha missile launchers fired countless bursts at the defenses, while more persistent targets from shorter distances were destroyed by tanks and lighter artillery. The artillery density was so great that the guns were often arranged side by side, wheel against wheel. At a certain point in the south, Rybalko had 650 guns at his disposal.per mile of front line

Most Soviet armies followed a strategy in which every infantry regiment was assigned a street daily. Two battalions advanced on either side of the road, with the soldiers exposing themselves as little as possible and usually blowing the partition walls between houses and cellars to move forward. Walls and doors were blown away with anti-tank guns or explosives. Fires broke out everywhere. A German soldier later said: "Gradually we lost our human appearance. Our eyes were burning and our faces were drenched and smeared by the dust around us. We could no longer see the blue sky; everywhere buildings were on fire, ruins collapsed, and smoke billowed back and forth through the streets. The silence that followed each bombardment was only the prelude to the engine roar and chattering of tracks that heralded a new tank attack."

Definitielijst

- cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- Leibstandarte

- Elite troops, originally Hitler’s body guards. Starting as a motorized infantry regiment it grew into a Panzer division.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Advance to the center

During the race between Zhukov's 1st Byelorussian and Konev's 1st Ukrainian Front, the two fronts were insufficiently aware of each other's positions. In addition, Zhukov was unaware that - after Zhukov's disappointing performance during the fighting at Seelow - Stalin had given permission to Konev to advance to Berlin. Chuikov's 8th Guards Army and Katukov's 1st Guards Tank Army were therefore very surprised when they arrived from the southeast at Schönefeld Airport in the morning of April 24 and found units of Rybalko's 3rd Guards Tank Army - Konev's armored spearhead. The news came to Zhukov only that evening, which he initially refused to believe, and ordered Chuikov to send "reliable staff officers" to determine which units were involved. It was clear that Zhukov had not been informed of Stalin's permission for Konev to participate in the Battle of Berlin. Subsequently, instructions came from Moscow that the demarcation line between the two fronts from the southern suburb of Lichtenrade would follow the railway to Anhalter station. This meant that the Tiergarten and the Reichstag were still within reach of Konev's troops.

Battles at the inner defense perimeter

After taking office as Kampfkommandant, Weidling went out of his way to improve the existing defense system, but it all had little effect at this late stage. He replaced a number of incompetent commanders and reduced the number of defense sectors. In the north, Hermanns 9. Fallschirmjägerdivision still held a position around the Flak tower in Humboldthain. The defense here was so unshakable that large parts of the area between the Spree and the northern section of the S-Bahn remained in German hands until the end. Krukenbergs 11. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision "Nordland" occupied positions in Neukölln and east of Kreuzberg. The division was seriously depleted; when Krukenberg took over command of Ziegler, a number of frontline soldiers were found to have withdrawn to rest and only 70 men were fighting. Mummerts Panzerdivision "Müncheberg" fought at Tempelhof airfield and still had ten tanks and 30 half-track vehicles. Rauchs 18. Panzergrenadierdivision, which was still relatively strong and had a good number of tanks and other vehicles, defended the Zehlendorf region in the southwest. Scholze's 20. Panzergrenadierdivision had been cut off on the Wannsee island between Zehlendorf and Potsdam and had only 92 soldiers.

As the Soviet troops moved closer to the heart of Berlin, the lines of defense became smaller and smaller. Despite heavy German losses, this meant that troop density on the front line increased, as did the percentage of experienced soldiers. A German officer stationed at the Reichskanzlei reported on April 25 that desertion was widespread among the Volkssturm units, but that Hitler Youth members were usually very loyal and courageous and that the regular army units fought with "calm determination". The inner lines of defense were also more solid, and their breakthrough was quite a challenge for the Soviet troops in a number of sectors. By 24 April, two Soviet armies had reached the S-Bahn line: the 3rd Shock Troops in the north and northeast (from Wedding to Prenzlauer Berg) and the 5th Shock Troops in the east and southwest (from Prenzlauer Berg to Treptow). In the north and east they encountered the Flak towers in park Humboldthain and park Friedrichshain, respectively, which offered fierce resistance. It was therefore decided to pass by the Humboldthain Tower, keeping it in operation until the end of the battle. The tower in Friedrichshain also slowed down the advance and was eventually passed by. The garrison there persisted until the morning of May 1. In other sectors, such as on the Frankfurter Allee in the east, the resistance was surprisingly weak.

Confusion between Konev and Zhukov

In the south, on the morning of the 24th, Rybalko crossed the Teltowkanal near the Zehlendorf district. Marshal Konev led the crossing personally. The Soviet troops met with strong opposition from the local defenders here, supported by Scholze's 20. Panzergrenadierdivision and parts of Rauchs 18. Panzergrenadierdivision. At the end of the day, Rybalko had penetrated about 1.2 miles into the German lines. Rybalko was still ahead of Chuikov and Katukov at this point, but Chuikov made rapid progress. He reached the Teltowkanal during April 24 and made the crossing the following morning. Then Chuikov captured Tempelhof Airport and turned more to the northwest, into the Schöneberg district, with his right flank along the Landwehrkanal. With this, Chuikov had crossed the front line Lichtenrade-Anhalter station and entered Rybalko's sector; either Chuikov was unaware of this line, or he consciously ignored it. With only the Landwehrkanal and the Tiergarten in front of him, it was only a few hundred yards for Chuikov to the Reichstag.

In the morning of April 28, General Rybalko's 3rd Guards Tank Army had also crossed the Landwehrkanal from the south. Assuming they were the first Soviet unit on the canal, Rybalko's artillery launched its preliminary bombing of the troops across the canal. Only after some time did it dawn on him that the enemy troops were really men of Chuikov's 8th Guards Army. Much to his disappointment, Konev realized that Zhukov had overtaken him. Konev was eventually forced to order Rybalko to turn west. Rybalko was seething and Konev was utterly disappointed that Zhukov would be given the honor of conquering the Reichstag.

Fighting in the Zitadelle

As the Soviet troops moved ever closer to the Zitadelle, Weidling introduced an outbreak plan to Hitler during the evening meeting on April 26. After some consultation with Goebbels, Hitler rejected the plan: "Your proposal is fine, but what is the purpose of all this? I don't want to wander around in the woods to be attacked there. I will stay here and will die at the head of my troops. You can continue the defense!" Nevertheless, Weidling and his staff continued to fine-tune the plan to put it into effect as soon as an opportunity arose.

As a result of Chuikov's fierce attacks, the German defenders of Krukenberg's Nordland division retreated across the Landwehrkanal on the night of April 26-27. Now that the fighting had reached the Zitadelle, new misunderstandings and communication problems arose. As a defense sector, the Zitadelle had its own commander, Oberstleutnant Seifert of the Luftwaffe, but the defense of the government district - including the Führerbunker and the Reichskanzlei - was the responsibility of the SS troops of SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke. Mohnke did not consider himself subordinate to Weidling or Seifert, and was directly answerable to Hitler. Krukenberg, who had unilaterally decided to make himself and his division available to Mohnke, also refused to listen to Weidling.

Living conditions in the Zitadelle gradually deteriorated. Because it was extremely dangerous on the streets as a result of the artillery shelling, large numbers of civilians had resorted to finding refuge in the S-Bahn tunnels. There were also countless injured people here, who could not be evacuated from the combat zone. A German lieutenant described the situation in the tunnels under the Anhalter station as follows: "The station looks like an army camp. Women and children hiding in the niches. Some sit on folding chairs and listen to the sounds of the battle. Grenades hit the roof, cement crumbles from the ceiling. Hospital trains slowly roll by". Various headquarters were also located in the underground corridors; for example, Krukenberg's headquarters was located in an abandoned rail car in the U-Bahn station Stadtmitte. He did not have electric light and telephone connections here. Every now and then an artillery shell broke through the roof, resulting in heavy losses. On the 27th, water suddenly poured into the tunnels below the Anhalter station, which led to many civilians and wounded drowning or being trampled in the panic that followed. It is unclear whether, despite its usefulness to civilians, wounded and military headquarters, it was deliberately flooded - so that the Red Army could not use it - or whether damage to the tunnels was the cause.

Fires, meanwhile, raged uncontrollably in much of the central districts. Because of the incessant artillery fire, firefighters were unable to do their job. The enormous smoke development made it almost impossible to drop supplies by German planes and to carry out bombing raids by Soviet planes. On the 26th, the telephone connections between the pocket and the outside world, which had only worked sporadically in the last two days, were permanently broken. The military communication systems no longer worked within Berlin, but the regular telephone network still worked. Therefore, in order to remain somewhat aware of the military situation, Krebs' staff was forced to dial random numbers from the phone book, reportedly occasionally talking to a Soviet soldier. A Soviet officer later claimed that he had been connected to Joseph Goebbels from Siemensstadt in West Berlin and had an unashamed conversation with him in German.

In the evening of April 29, during the last discussion about the situation in the Führerbunker, Weidling sketched a grim picture. The ammunition had almost run out and ammunition drops were no longer possible. Weidling considered it inevitable that the fighting would end within 24 hours. Mohnke agreed with this estimate. Weidling asked Hitler what to do as soon as the ammunition ran out, after which Hitler indicated that "small groups" could break out. The total surrender of Berlin, on the other hand, Hitler continued to prohibit categorically.

Weidling still had close to 30,000 combat-worthy troops holding a 8.5 miles strip from Alexanderplatz in the east to the Havel in the west. The strip was only a mile wide in some sectors. During the day the Spree was reached in several places in the north. Berzarin's 5th Shock Troop Army had crushed most of the resistance east of the Spree, and further to the southwest Berzarin's left flank had captured Anhalter station. From the south, countless small storm groups of Chuikov's 8th Guards Army fought their way across the Landwehrkanal with rafts or via the handful of remaining bridges. Concealed German artillery and machine guns inflicted heavy losses on the Soviet infantry, but by the end of the day, Chuikov had captured Potsdamer Platz and had reached the Großer Tiergarten.

Break out and attempts at relief

Further west, the pressure on the German lines was less. Rauch's 18. Panzergrenadierdivision stood on the S-Bahn line from Westend to Hohenzollerndamm. Rauch realized that Heerstraße, and above all both bridges over the Havel at Pichelsdorf that this street used, had to remain in German hands for a possible outbreak. Two bridges were also intact a few hundred yards further north. The bridges and Heerstraße were defended by a Hitler Youth regiment that originally consisted of 5,000 boys; as a result of heavy artillery fire, only 500 of them were still able to fight. Some superfluous adjutants and liaison officers from the Führerbunker made good use of this opening on the 29th and managed to escape by going down the Havel to the south.

On April 26, Wenck had made an attempt at dawn with the XX. Armeekorps under General der Kavallerie Carl-Erik Koehler, which managed to surprise the weaker Soviet troops southwest of Potsdam. Quite a few Red Army logistic units and workshops were captured intact, and Koehler was ultimately 15.5 miles from Berlin. There was some contact with the garrison of Potsdam, but on April 29 XX. Armeekorps could do nothing but defend themselves in the area south of Schwielowsee. Another planned attack to be carried out by Generalleutnant Rudolf Holste's XXXXI. Panzerkorps from the Rathenow region west of Berlin never got off the ground.

Just before midnight on April 29, Hitler asked the OKW for the last time about the status of the attempts to relieve Wenck and Busse. At one o'clock in the morning he received an answer from Keitel: Wenck's spearhead had stalled due to fierce Soviet attacks south of Schwielowsee, Busse's 9. Armee was surrounded and parts of it tried to break out to the west and Holste's XXXXI. Panzerkorps had gone into defense around Rathenow. Because relief was not forthcoming, Hitler`s only way out was suicide. Mohnke estimated that the Soviet troops would launch a major attack on the Reichskanzlei in the early morning of May 1.

Battle at Halbe

Theodor Busse's greatly weakened 9. Armee, which had been surrounded since the beginning of the battle of Berlin, was now almost continuously bombarded by land and air forces of the Red Army. Busse realized that a connection to Wencks 12. Armee was the only way to keep his troops out of the hands of the Red Army and so decided on the 25th to launch a breakthrough westward. Only later did Busse receive Hitler's unrealistic orders to launch an attack in the direction of Berlin together with Wenck. Both Wenck and Busse viewed the plan purely as a rescue operation, intended to keep Busse's troops out of the hands of the Red Army.

From the wooded area between Lübben and Halbe, Kampfgruppe von Luck (Oberst Hans von Luck) and Kampfgruppe Pipkorn, SS-Standartenführer Rüdiger Pipkorn) led the outbreak of Busse's three corps. From Baruth, the Soviets fiercely resisted, killing Pipkorn on April 25 and taking von Luck prisoner on April 27. Busse's main force also suffered heavy losses, but made another attempt at attack in the evening of April 28. The attack was concentrated on a narrow front line at Halbe, the border between the two Soviet fronts, where the German forces had to force a breakthrough like a wedge. After a night of fierce fighting, a breach was made in the Soviet lines. Two corps managed to escape, but the V. SS-Freiwilligen-Gebirgskorps, parts of the 21. Panzerdivision and most of the refugees were left behind. The stragglers fought desperately, with both sides suffering heavy losses, but the attention of the other two corps was also diverted. Constantly harassed by Soviet troops, they managed to break through two cordons. Finally, exhausted, they reached Wenck's lines on the morning of May 1. Busse estimated that some 40,000 troops and a few thousand refugees had reached 12. Armee; Soviet estimates were considerably lower. Be that as it may, most of the 9. Armee had been killed or captured, but in view of the circumstances the contact was a great achievement.

Definitielijst

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

The Red banner on the Reichstag

The iconic photo of the Soviet soldier hoisting the red banner on the Reichstag building, with a destroyed Berlin in the background, became world famous immediately after publication. In the eyes of many, the image of the Soviet flag on the Reichstag meant that the Third Reich had perished, and long before the battle of Berlin, the Soviet High Command had decided that the Reichstag would be the ultimate target of the attack. But actually, this was a special choice. The Reichstag building was built in 1894 to serve as the seat of the German Parliament, and in that capacity the building was used by the German Empire (1871-1918) and then the Weimar Republic (1919-1933). The iconic words Dem Deutschen Volke ("To the German people") gave the building a democratic appearance. The Nazi regime, on the other hand, did not use the building; in February 1933, shortly after Hitler's seizure of power, the well-known Reichstag fire broke out and the building was only partially repaired after this. Nevertheless, it soon became clear to the Soviets, possibly as early as the summer of 1943, that the Reichstag would become the ultimate goal of the campaign and symbolize the Third Reich. Perhaps the fact that the building was clearly recognizable and that it was a practical military target because of its dimensions and detached location. Bombs were painted with the text "For the Reichstag" and tanks were marked "On to Berlin".

The race to Tiergarten

Konev's troops might have turned around on April 25, but for the armies of the 1st Byelorussian Front, the race to the Reichstag was not over yet. From the Kremlin, heavy pressure was put on Zhukov's armies to raise the flag on the Reichstag as soon as possible, preferably before May 1 (Labor Day). This phase of the battle of Berlin is not only important because of the irrational importance attached to the conquest of the Reichstag: with its politically motivated deadline, it was also illustrative of the way the operation was conducted on the Soviet side, in which hasty military decisions led to unnecessary losses. In the morning of April 29, Chuikov prepared to cover the last 400 yards but the dense build-up and fierce resistance from German troops hindered his advance. However, there were other armies in the running. To the east, Berzarin's 5th Shock Troop Army had reached Leipziger Straße and were less than a mile from the Reichstag. The formation that was to take credit was nevertheless General Perevyortkin's 79th Pursuit Corps of General Kuznetsov's 3rd Shock Troops, which had approached the Spree from the northwest via Alt-Moabit. In the afternoon of April 28, the first units of the 79th Jägerkorps saw the Reichstag through smoke. Guards of the 150th Pursuit Division (under Major General Shatilov) and 171st Pursuit Division (under Colonel Negoda) managed to cross the Spree via the Moltkebrücke on the night of April 28-29. At 04:00 in the morning of April 30, the 150th Pursuit Division had captured the Ministry of the Interior - also known as "Himmler's House" - 200 yards away. Half an hour later, the exhausted soldiers - without thorough reconnaissance or a thorough artillery bombardment - were sent to Königsplatz, but from the Reichstag, the Tiergarten on the right flank and the ruins of the Kroll opera behind them, the soldiers were heavily targeted. It was not until April 30 that the two divisions finally managed to cross Königsplatz and reach the Reichstag.

The question of who first hoisted the banner of victory on the roof of the Reichstag was the subject of much debate after the war, not least because it was promised that the soldiers who succeeded first would be appointed Hero of the Soviet Union. Prior to the offensive, the staff of the 3rd Shock Troop Army had issued nine so-called victory banners (znameni pobedy) to its divisions to hoist on the Reichstag. With the Reichstag in sight, General Shatilov gave banner no. 5 to Colonel Fyodor Zinchenko's 756th Fighter Regiment, which again passed it to the 1st Battalion under Captain Stepan Neustroyev. Vasily Davydov's 1st Battalion of the 674th Fighter Regiment also received a flag, as did First Lieutenant Konstantin Samsonov's 1st Battalion of the 380th Fighter Regiment. Also, banners went to two special storm groups formed by General Perevyortkin's headquarters. One was led by Major Mikhail Bondar, Perevyortkin's adjutant, and the other by Captain Vladimir Makov, a staff officer.

In the Reichstag

On April 30, several storm groups, some 300 men in total, invaded the Reichstag. Reaching the roof proved to be quite a task as thousands of SS troops fiercely resisted the various floors for hours. Only late in the evening did a unit of four sergeants led by Captain Makov manage to get to the roof. One of the sergeants, Mikhail Minin, finally hoisted the victory banner on the Germania sculpture above the pediment at 10:40 PM. The corps commander, General Perevyortkin, was immediately informed of this by radio. Major Bondar's storm group arrived a short time later and placed a second banner above the pediment. Makov's group guarded the banners and stairs on the roof until 5:00 a. m. on May 1, when the group left the Reichstag.

As the storm groups of Makov and Bondar fought their way up, another unit headed for the roof bearing Neustroyev's flag. This group, consisting of sergeants Mikhail Yegorov and Meliton Kantaria under the leadership of Lieutenant Aleksei Berest and supported by a machine gun company under Sergeant Syanov, managed to get past the German defenders with great difficulty. In the early hours of May 1, this group raised its flag on the southern side of the roof. At the time, there were no further banners visible on the roof. Because fires were raging all over the Reichstag, the other two flags were believed to have been burned or taken away by the Germans - who resisted Weidling's capitulation order on May 2. Because the storm group from Berest arrived on the roof just after midnight, this version is not in line with Minin's claim that his group guarded the roof until 05:00 in the morning. According to other sources, Berest's group managed to place a banner at the same time as Makov's group, or even earlier, around 9:50 PM.

In any case, because a missing banner could hardly serve as a symbol of victory, the storm group of Berest got all the credit. Their victory banner was marked "150th Order of Kutuzov 2nd Class Idritsa-Pursuit Division, 79th Pursuit Corps, 3rd Shock Troops, 1st Belarusian Front" and was flown to Moscow on June 20, 1945 by Samsonov, Neustroyev, Kantaria, Yegorov and Syanov. There the standard still has its own hall in the Central Museum of the Armed Forces. The scouts Kantaria and Yegorov, battalion commander Neustroyev, regimental commander Zinchenko, division commander Shatilov and corps commander Perevyortkin were later all appointed Hero of the Soviet Union. Berest was ignored for unknown reasons; he, like the men of Makov's group, he had to make do with an Order of the Red Banner. Berest was only posthumously awarded the title 'Hero of Ukraine' in 2005.

Yevgeny Khaldei`s picture

The hoisting of the first flags on the Reichstag building has not been recorded, partly because there was still heavy fighting in the building until 2 May. The world-famous photo of the flag placed on the roof against the background of a destroyed Berlin has therefore been staged. Photo correspondent Yevgeny Khaldei was instructed by TASS Press Agency to take a picture of the moment a flag was raised on the Reichstag. Shortly after the fighting in Berlin ended, Khaldei went to the roof of the Reichstag building. Here he asked three soldiers of the 8th Guards Army, who just happened to be there, Aleksei Kovalyov, Abdulkhakim Ismailov and Leonid Gorichev, to re-enact the hoisting of the flag, of which Khaldei took a series of photos. Kovalyov held the flagpole, assisted by Ismailov and Gorichev. So the photographers were not Kantaria, Yegorov and Berest, as is often claimed. Khaldei says he was inspired by the photo taken by Joe Rosenthal two months earlier of the placement of the American flag on Mount Suribachi on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima. Both photos are among the most famous from World War II.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Germania

- The capital of the Third Reich after the war. Designed by Albert Speer, but never realised.

- Kremlin

- Soviet administrative centre in Moscow.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Reichstag building

- German government building in Berlin.

- Reichstag fire

- On the 27 February 1933 the building of the German government was set on fire. The Germans could declare a state of emergency and hereby come into power. It is not known whether the fire was started by the Nazi’s or the communists. The Dutchman Marinus van der Lubbe was in any case condemned for the crime.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Weimar Republic

- Name for the German republic from 1919 until 1933. Hitler ended the Weimar republic and founded the Third Reich.

End of the battle

Hitler was married on the evening of April 28 to his girlfriend, Eva Braun, who had accompanied him in the bunker from the beginning of April and refused to leave Berlin. After noon on April 30, as Soviet troops made their way to the roof of the Reichstag, the two retired to their quarters in the Führerbunker. There they committed suicide at 3:20 PM. Their bodies were placed in a pit in the garden of the Reichskanzlei, doused in petrol, cremated and then buried in a bomb crater.

Negotiations

Weidling had agreed with his sector commanders that an outbreak attempt would be made on April 30 at 10:00 PM, but a few hours before, he was summoned by Krebs to the Führerbunker. Here Krebs revoked Hitler's previous permission to break out; he indicated that he wanted to negotiate a German surrender with the Soviet High Command. Weidling was "deeply shocked" and saw it as a senseless game of power by Goebbels and Bormann that only meant that the suffering of the civilian population would continue and that the troops would continue their senseless struggle.

Wilhelm Mohnke as SS-Standartenführer, shortly after the Ritterkreuz was awarded to him. As far as is known, there is no picture of him in the uniform of a Brigadeführer. Source: Unknown

In the afternoon of April 30, contact was made with a division of General Berzarin's 5th Shock Troops. Just after midnight, Krebs and Theodor von Dufving, Weidling's "military" chief of staff, and SS-Untersturmführer Neilands, a battalion commander who acted as interpreters (although Krebs spoke Russian fluently), went to the Soviet lines. Near the Anhalter station, they crossed the front line and were taken by jeep to General Chuikov's headquarters at the Schulenburgring. The discussion lasted several hours: Krebs sought to gain recognition for the new German government, which, according to Hitler's political will, was now led by Joseph Goebbels as Reich Chancellor, with Karl Dönitz as Reich President. The Soviets, in turn, were only interested in an unconditional surrender, and Krebs was not authorized for such discussions. It was therefore decided that contact should be made by telephone with Goebbels in the Führerbunker. An attempt to install a telephone cable failed, after which Krebs returned to the Führerbunker and decided to send the Soviets a written response. Since the Soviets were clearly not interested in a truce with a National Socialist government, even if it was a pro-Russian one, and could only accept an unconditional surrender, Goebbels recognized that further negotiations were pointless. With the help of an SS doctor, the six children of Joseph and Magda Goebbels were killed in their sleep by administering cyanide. After this, Goebbels and his wife left the Führerbunker and committed suicide in the garden of the Reichskanzlei.

Last resistance

Because Krebs' request for a truce had been rejected and no contact had been made with the Führerbunker, the offensive was resumed in the afternoon of May 1 — Labor Day. After a heavy preliminary artillery bombardment, one of Chuikov's corps opened fire on the defenses of the Zoo, where the Flak tower was still in operation and continued to fire on the Soviet troops in the southeast and at the Reichstag. Since the tower was strong enough to withstand direct hits from 203mm howitzers, a direct storm was waived and the Soviets sent a surrender proposal to the tower commander on April 30, guaranteeing that no German soldier would be executed. Late in the evening of May 1, the Germans agreed to the offer and at midnight the garrison surrendered.

The area to the south and west of the Zoo was defended by Mummert's Müncheberg division, and on the night of 1 to 2 May, scouts of this division discovered that the Soviet troops in the Spandau district were quite weak, so an outbreak was still a possibility. Some officers saw the most salvation in a westward outbreak attempt, but Mohnke decided to break through northward towards the Flak tower in Humboldthain and then turn northwest. Several plans were drafted. Late in the evening of May 1, Weidling gathered as many officers and NCOs as possible at his headquarters in the Bendlerblock for a meeting. He indicated that Hitler had committed suicide and thus had broken his oath, relieving the German military of their personal oath to Hitler. It was decided that Weidling would start negotiations with the Soviets just after midnight and that any outbreak attempts should be made prior to that.

Attempts at break out

Late in the evening of May 1, while the Flak tower surrendered, Generalmajor Otto Sydow of 1. Flak-Division attempted an outbreak from the Zoo. With the remaining tanks and half-track vehicles of Panzer-Division "Müncheberg" and the 18. Panzergrenadierdivision led the way by several hundred soldiers and several hundred civilians to reach the bridges in Spandau. The last five miles were covered in silence and without light through the U-bahn tunnels, beneath the Soviet lines. Amazingly, they managed to escape unnoticed. Other units, including a group of soldiers and armored vehicles from the Müncheberg division, clashed with Soviet troops and suffered losses in the attempted escape. The Charlottenbrücke, one of the more northerly bridges over the Havel, was the scene of a gruesome slaughter. In the pouring rain and violent artillery fire of the 47th Army, vehicles and a ragged crowd of soldiers and civilians rushed across the bridge, many killed by Soviet fire, trampled or run over by armored vehicles.

The units that chose an outbreak to the north were lucky. Major Lehnhoff's Wachregiment "Großdeutschland" suffered heavy casualties, but five tanks and 68 soldiers managed to reach Oranienburg. The tanks had to be abandoned here because of technical defects, but the troops managed to escape. Several small groups also attempted an escape from the Führerbunker. SS-Brigadeführer Mohnke had divided those present into ten groups and devised some escape plans. The first group, led by Mohnke, managed to reach the Spree via the U-Bahn tunnels, crossed the river via a small footbridge and reached the northern districts of Berlin through a wilderness of ruins. For groups that left later, the escape became more and more difficult, as the Soviet troops were alarmed by less attentive Germans following an above-ground route. SS-Brigadeführer Krukenberg's group, supported by a Tiger II and five half-track vehicles, was ambushed not far from the Gesundbrunnen U-Bahn station and lost many troops to enemy fire. Krukenberg's predecessor, SS-Brigadeführer Joachim Ziegler, was among those killed. Only Krukenberg escaped with a handful of survivors.

The other Nazi leaders from the Führerbunker, who jointly undertook an outbreak, ended differently. Werner Naumann, Goebbels' Secretary of State for Information and Propaganda, managed to flee the city. SS-Gruppenführer Hans Baur, Hitler's personal pilot, was seriously injured and taken prisoner of war. Artur Axmann hid in Berlin and later escaped to the West. Martin Bormann and Ludwig Stumpfegger, Hitler's personal physician, committed suicide; their bodies were buried a few days later and only discovered in 1972. Hans Krebs and Wilhelm Burgdorf decided to stay in the Führerbunker and committed suicide there.

Surrender