Prior to the war

Introduction

During the war, Konrad Morgen served in the SS as investigative judge. One of the cases he was involved in, was that of Karl Otto Koch, the commander of concentration camp Buchenwald from 1937 to 1941. Morgen was outraged about the facts he discovered during his investigation in the camp; together with a few cronies, Koch had stolen from inmates, had tortured them and murdered them without having been given official permission. For these reasons, he and a number of codefendants including his wife Ilse, notorious among the inmates for her cruelty, were subpoenaed by the SS. An SS court sentenced them to death. As late as April 5, 1945, with the Americans approaching the camp, Koch was executed in Buchenwald by an SS firing squad.

With the knowledge of the crimes committed by Nazi-Germany we have today, it appears exceptional that Koch and his wife were prosecuted for crimes which to us are synonymous with the system of the German concentration camps where theft, torture and murder were the order of the day. Koch was not the only member of the camp staff though who faced a similar investigation by Konrad Morgen. After Buchenwald, he launched investigations into crimes committed by members of the staff in various other large camps including Auschwitz.

This article is a summary of the book ‘A Judge in Auschwitz’ by the same author.

Study and membership of the SS and NSDAP

Valentin Georg Konrad Morgen was born June 8, 1909 in Frankfurt am Main. His father was a train driver. In 1929, Konrad passed his final exam at the Oberrealschule. Subsequently he studied law at the universities of Frankfurt am Main, Rome and Berlin. He also studied at the Academy of International Law in The Hague and the Institute of World Economics and Shipping in Kiel. After the successful completion of his studies, he was allowed to call himself Doctor of Law. Being specialized in international law, a brilliant career was waiting for him in Hitler’s ‘new’ Germany, where young academics like him enjoyed ample career opportunities, provided they were loyal to National socialism and enrolled in the Party or some partner organization.

After the war Morgen claimed he felt little enthusiasm for National socialism prior to Hitler’s rise to power. He considered himself a ‘National liberal’. Not long after Hitler’s appointment as Reichskanzler in January 1933 though, he joined the ranks of the National socialists. On March 1, 1933, he enrolled in the Allgemeine SS, the civil branch of the SS. One month later, he became a member of the NSDAP. The reason for his membership that he named after the war was that this was necessary to continue his studies (he was in his sixth semester). He claimed he had not participated in party activities. He was a member though of the Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (NSDStB or Nazi Student Union) and the NS-Rechtswahrerbund or Union of Nazi lawyers. He appears to be one of the many opportunists who joined the party after it had come to power.

In 1936, Morgen published a book entitled Kriegspropaganda und Kriegsverhütung (War propaganda and prevention of war). In his book he did not call for war in so many words, but the message was far from pacifistic nonetheless. Morgen actually distanced himself from the ‘antimilitaristic-pacifistic propaganda’ that, according to him, ‘employed exactly the same methods as the actual war propaganda’. In his book, Morgen spoke out in favor of National socialism. The struggle it had to make was, in his opinion, one not with weapons but with diligent labor.

In 1939, prior to the war, Morgen was employed by the Landesgericht in Stettin as a lawyer and judge. During a trial, in which he sat as a deputy judge, he collided with the chairman of the court whom he considered prejudiced. On April 1, he was fired for disciplinary reasons. After the war he used this dismissal as proof of his critical attitude towards the regime. Nonetheless, he found new employment in a National socialist organization. In Pomerania, he went to work as a legal advisor for the Deutsche Arbeiterfront (DAF, the Nazified workers union). Among other things, he supported workers during trials.

Definitielijst

- Allgemeine SS

- “General SS”. The civilian branch of the Schutzstaffel (SS). Since 1939 the counterpart of the Allgemeine-SS was the Waffen-SS, (the military branch of the SS). The Allgemeine-SS was the backbone of the organisation and the source for recruiting the men for the Waffen-SS, the SD (Sicherheitsdienst) and the Totenkopfverbände. During the war years the Allgemeine-SS was involved in amongst others in local politics and administrative and government business.

- Buchenwald

- Concentration camp established in 1937 near the city of Weimar.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- National socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Investigator of corruption

In the General Government

After the outbreak of war, Morgen joined the Hauptamt SS-Gericht. He started his career within this legal branch of the SS with a period of training in Munich and in January 1941, he was transferred to the SS und Polizeigericht as deputy judge in Krakow, the capital of the General Government in Poland. March 1, 1941, saw him promoted to SS-Untersturmführer. A few months after his appointment, he unraveled a corruption scandal within a supply depot of the SS. He had the chief of the depot, SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Georg von Sauberzweig and his staff of forty people arrested on charges of serious property crimes. Von Sauberzweig had sold possessions, confiscated from Poles, and had shared the revenue with subordinate accomplices. Despite his record as party old-timer, on August 1941, the SS und Polizeigericht in Warsaw sentenced him to death by a firing squad. On March 9, 1942, the sentence was confirmed by the Führer and he was executed on April 9, 1942.

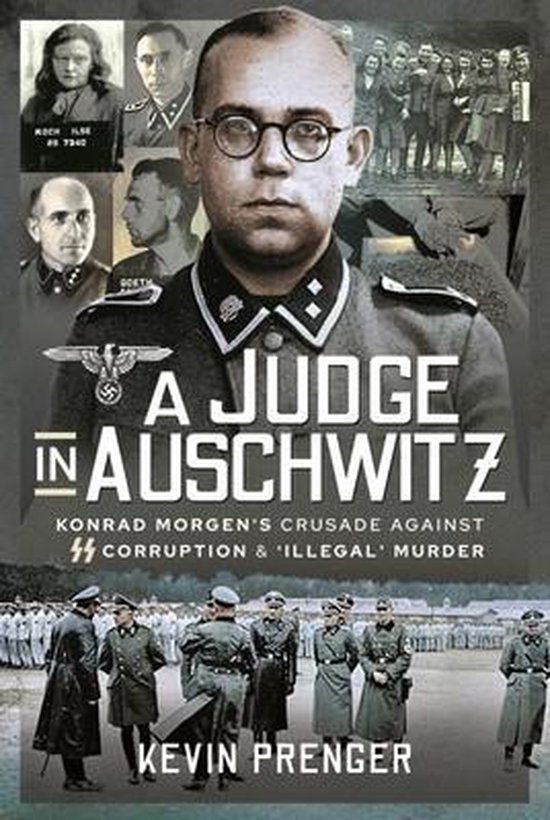

The case against Von Sauberzweig put Morgen on the trail of another corrupt SS officer: Hermann Fegelein, a protégé of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. During the war, Fegelein commanded the 8.SS-Kavallerie-Division, but he became known mainly as the husband of Eva Braun’s sister Gretl, whom he married in 1944. In the course of his investigation into Von Sauberzweig, Morgen discovered that large quantities of luxury goods had been sold to the SS depot by members of Fegelein’s regiment under suspect conditions. In addition it transpired that Von Sauberzweig had transferred the direction of a fur shop, confiscated from a Jew, to an SS officer from said unit. When Morgen opened an investigation into an alleged corruption web around Fegelein, he was suddenly taken off the case by Himmler. The investigation was swept under the rug. Undoubtedly, Himmler acted in this way because a corruption scandal being unearthed involving one of his favorite officers would seriously blemish the reputation of his SS.

Within the SS there was no question of an independent jurisdiction, which is made obvious by the fact that Himmler had the authority to suspend any criminal investigation. This also became clear during another investigation by Morgen in the General Government, the case against SS-Obersturmführer Dr. Oskar Dirlewanger. This officer, notorious for his cruelty, commanded the so-called SS-Sonderkommando Dirlewanger, an armed SS unit made up of convicted poachers, murderers and rapists. In Poland, the unit was involved in guarding Jewish forced laborers. Dirlewanger had his men arrest Jews and subsequently demanded a ransom for their release. Those who wouldn’t or couldn’t pay up were executed. In addition, in the Lublin ghetto, the Sonderkommando had been guilty of looting. The bounty was sold back to the former owners. Dirlewanger himself was suspected of having entertained sexual relations with Jewish girls. This was strictly forbidden by the Nuremberg racial laws.

Hermann Fegelein, June 21, 1941. Morgen suspected him of corruption, but was not allowed to continue his investigation into him. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101III-Bueschel-056-13 / Büschel / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Oskar Dirlewanger,1944. He too was protected by the SS leadership when Morgen investigated him. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S73495 / Anton Ahrens / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Dirlewanger’s superior, Gottlob Berger, chief of the SS-Hauptamt, refused however to agree to the prosecution of his protégé. Instead of being taken to court, he was transferred to Belorussia. Consequently, Morgen had to abort his investigation into Dirlewanger as well. As he had enough of the corruption in the General Government, in March 1942, he asked to be transferred to a quieter post. His superiors had something quite different on their minds though. He was stripped of his rank of SS-Obersturmführer, to which he had been promoted on April 20, 1942, and he was degraded to SS-Sturmmann, the lowest rank in the SS. Moreover, he was transferred to a penal company in Stralsund in northeastern Germany. In December 1942, he was posted to the regiment ‘Germania’ of the Waffen-SS Division ‘Wiking’, which at that time was fighting in the southern sector of the Eastern front.

Official documents are missing but after the war, Mogen named as the reason for his promotion and degradation that Himmler had been outraged about the way he had dealt with a case against a German policeman in early 1942. The man had been charged with sexual contact with a Polish woman. Although Himmler had expressly forbidden intimate contacts with Polish women and had insisted on severe penalties, Morgen had dismissed the case as irrelevant. Himmler considered Morgen’s conduct an act of sabotage and therefore Morgen would have been ousted from his function and eventually sent to the front. The Reichsführer-SS is said to even have threatened him with two to three years in a concentration camp but would have abstained thanks to protests by Morgen’s superiors within the Hauptamt SS-Gericht. According to Morgen, the issue with the policeman had been passed on to Himmler by the enemies he had made in the General Government as a result of his investigations into corruption.

A case of corruption in Buchenwald

Nothing is known about the time Morgen spent in the ‘Wiking’ division on the Eastern Front. As early as May 1943, Himmler recalled him to Germany where he was fully rehabilitated. Actually, the SS leader could make very good use of Morgen’s expertise as fighter against corruption. He was reinstated in his rank and assigned as investigative judge, to the department of economic crimes of the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt, the head office of the German criminal police. The case, for which Morgen’s expert knowledge was required, was a big case of corruption in concentration camp Buchenwald, close to Weimar. For Morgen, this was the beginning of a long string of investigations into corruption and other crimes in these German camps.

Morgen was sent to Buchenwald where camp commander Karl Otto Koch had conducted a mismanagement between July 1937 and September 1941. The SS- und Poliziegericht in Kassel had discovered a case of corruption involving Koch. A young detective had launched an investigation into Ortsgruppenleiter Bornschein. This local party leader and food merchant was suspected of having been involved in various cases of fraud, together with Koch. In order to thwart Bornschein’s persecution, Koch had made him a member of his camp staff. As such he did not have to fear the policeman as the latter had no authority within the concentration camps. A judge with an officers rank in the Waffen-SS did have that authority, hence in the spring of 1943 Konrad Morgen set off for Weimar and gained access to the camp. Before long he had gathered ample evidence against Bornschein so he could be sentenced to nine years imprisonment.

Morgen found out that Bornschein was only small fry compared to camp commander Koch. Together with a number of accomplices, including his wife Ilse, he had enriched himself in uninhibited fashion with the possessions and money of his prisoners. Allegedly, inmates would have given money to Koch and his cronies to evade corporal punishment. Morgen also learned from various witnesses that rich inmates had paid Koch for their release. Much of the money, illegally expropriated by him and his people, originally belonged to the some 10,000 Jews who had been temporarily imprisoned in the camp after the November 1938 Kristallnacht.

Moreover, Morgen discovered in the camp administration that many prisoners who possibly knew about Koch’s criminal activities had passed away. He established that their death certificates had been forged. Morgen counted some 160 inmates who had been murdered in Buchenwald prison, usually by intravenous injections with phenol. The number of inmates who had been murdered in a similar way in the sick bay "couldn’t be guessed at" according to him. In addition, 120 prisoners had been "shot while trying to escape" in the stone quarry of Buchenwald. Morgen established that "many of these executions" should be considered "unlawful killing of prisoners" as orders hadn’t been given accordingly.[1] He gathered ample evidence to have Koch and his wife arrested in August 1943. Other members of the camp staff were picked up as well, including the camp physician SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Waldemar Hoven and the guard SS-Hauptscharführer Martin Sommer. It had been doctor Hoven who had administered lethal injections to prisoners on orders from commander Koch. He was often assisted by Sommer who was known as the ‘hangman of Buchenwald’ for his sadism.

Because Himmler had agreed to his investigation into the corruption network and other crimes in Buchenwald, Morgen finally seemed to be on the side of the fortunate. But even this case didn’t proceed without problems. In the camp, one of his most important witnesses, camp guard SS-Hauptscharführer Rudolph Köhler was found in his cell one day, where he stayed because he was a suspect himself, with serious symptoms of poisoning. He was transferred to the military hospital in Weimar where he passed away, despite the efforts of the physicians. Morgen immediately assumed it was murder by poisoning. The deceased was in possession of incriminating information about commander Koch. Morgen suspected the camp physician, dr. Hoven, of having poisoned the man. Conclusive evidence of murder couldn’t be found however and the case was never solved.

As late as September 1944, the case against Koch and his cronies was heard by the SS und Polizeigericht in Weimar. Not Morgen but other judges were to pass verdict on the charges he had drawn up. The trial was attended by SS-Gruppenführer Richard Glücks, chief of the Inspektion der Konzentrationslager (Inspection of concentration camps) and a high ranking official in Oswald Pohl’s SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt (SS-WVHA). Its leadership attempted to prevent its subordinates from being sentenced. Meanwhile, Morgen had been transferred to Krakow and he was involved as a witness only. The eventual verdict must have sounded a little disappointing to him: Koch and his wife were only charged with corruption by the court and not, as Morgen had wished, with arbitrary killing of inmates. Ilse Koch was acquitted for lack of evidence, whereas her husband was pronounced guilty and sentenced to death. On April 5, 1945, about a week before camp Buchenwald was liberated by the Americans, Koch was executed by an SS firing squad in the camp.

Dr. Waldemar Hoven and Martin Sommer were more lightly punished by the SS in comparison with their former commander. Their cases were tried separately from Koch’s. Dr. Hoven was imprisoned in Buchenwald until his case was dismissed in March 1945 and he entered service again as camp physician. Sommer was also kept in custody by the SS until he was posted to a penal company of the Waffen-SS in March 1945. He subsequently served at the front where he lost an arm and a leg.

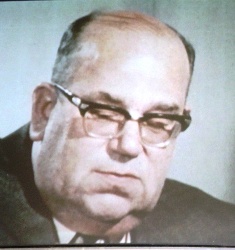

The second person from the left is Konrad Morgen. Location, date and the identity of the other persons are unknown. Source: Fritz Bauer Institut

Definitielijst

- Buchenwald

- Concentration camp established in 1937 near the city of Weimar.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Germania

- The capital of the Third Reich after the war. Designed by Albert Speer, but never realised.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Morgen's investigative committee

Investigation committee

The case against Koch and his cronies took Morgen to concentration camp Majdanek in eastern Poland as well. From September 1941 until August 1942, Koch had been its first camp commander. Morgen established that Koch and his staff members had continued their corruption activities, ‘illegal murders’ and atrocities. During his investigation in Majdanek he encountered resistance as well: all possible Jewish witnesses would have been murdered before they could have made a discriminating statement against the leadership of the camp. Nonetheless, sufficient evidence was found to arrest former member of the staff, SS-Obersturmführer Hermann Hackmann. Meanwhile he was serving in the Waffen-SS but he had been employed as a member of Koch’s staff in both Buchenwald and Majdanek. On June 29, 1944, he was pronounced guilty of embezzlement by the SS und Polizeigericht in Kassel and sentenced to death. It didn’t get that far because he was released from penal camp Dachau before the end of the war and posted to a penal company.

Another colleague of Koch who was arrested in connection with the investigation into corruption was SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Florstedt. From July 1, 1940 onwards, he was employed as Schützhaftlagerführer, first in Sachsenhausen and later in Buchenwald. On November 25, 1942 he was appointed successor to Koch as commander of Majdanek. On October 23, 1943, the SS-Personalhauptamt was informed that Florstedt "had been arrested on orders of the Reichsführer-SS on charges of embezzlement and other serious crimes,"[2] and had been transferred to Buchenwald by judge Morgen for interrogation. Today, much is still unclear about Florstedt’s fate. Many historians assume that he was executed by the SS in April 1945 in Buchenwald, just like Koch. Peter Lindner however, who wrote a biography of Florstedt, doesn’t believe so: he is convinced "that Florstedt survived under an alias and possibly died peacefully."[3]

Hermann Florstedt, also sentenced to death by the SS for embezzlement and serious crimes. Whether the death sentence was carried out is unclear. Source: H.E.A.R.T.

The Buchenwald case was the beginning of a number of criminal investigations into corruption and other crimes in German concentration camps in the years 1943 and 1944. Special investigative commissions, coordinated by Morgen and consisting of SS judges, traveled to concentration camps in order to gather evidence. Other camps where Morgen and his team conducted investigations were Auschwitz, Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Vught, Krakow, Plaszów and Warsaw.

Within the SS, Morgen’s work earned him the nickname ‘the blood judge’, he said. He claimed to have dealt with 800 cases (often involving numerous persons), of which 200 eventually resulted in a sentence by a court. Other camp commanders than Koch and Florstedt who were investigated by Morgen included Amon Göth, commander of camp Plaszów, Adam Grünewald of Vught, Karl Künstler of Flossenbürg, Alex Piorkowski of Dachau and Hans Loritz of Sachsenhausen. All of them were relieved of their functions as camp commander by the SS. The impression has emerged that all these persons had been brought to trial thanks to Morgen’s efforts to be fired subsequently, but as far as Künstler, Piorkowski and Loritz are concerned, the truth is different. Morgen launched his investigation only after they had been fired by Oswald Pohl who replaced one third of his camp commanders, mostly for their incompetence.

Amon Göth, the sadistic commander of Plaszów. Arrested by the SS on charges of corruption, assault and murder, but he escaped punishment. Source: Yad Vashem

Lublin

In the fall of 1943 Konrad Morgen learned, in his own words, about the mass murder of Jews for the first time. He encountered two traces: one leading to Lublin, the other to Auschwitz. The first was a case of an unidentified Jewish labor camp in Lublin. During the Nuremberg trial, Morgen stated his attention had been drawn to this case by a report of the local commander of the Sicherheitspolizei. It said that in this camp, a Jewish wedding had taken place with 1,100 guests. There would have been a question of "excessive consumption of food and alcoholic beverages". The worst part was that members of the SS would have been present at the wedding. Morgen suspected that criminal activities had taken place and left for Lublin.

Morgen found out that SS-Sturmbannführer Christian Wirth was in charge of the camp and at the same time he was the inspector of Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka, the extermination camps that were established to carry out Aktion Reinhard. To his astonishment, Wirth admitted this marriage had taken place in the presence of his subordinates. "I asked him why he allowed members of his unit to do such things," so Morgen said, "and then he informed me that the Führer had ordered him to carry out the extermination of the Jews." The marriage was intended to deceive the Jews. It was his strategy to win over Jews who worked for him with special privileges, making them believe they would stay alive and continue to work for him.

Christian Wirth, the inspector of the Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka death camps. Morgen claimed to have tried to bring him to justice, but without success. Source: Yad Vashem

Not much more is known about the investigation Morgen carried out in Lublin. He claimed himself he would have pursued Wirth "to his death."[4] Morgen even would have followed him when the latter was transferred to the Adriatic coast where he was deployed fighting partisans. What we do know is that Morgen’s research has not led to Wirth’s prosecution. He probably lost his life on May 26, 1944 near Trieste in combat with partisans.

Auschwitz

In the same period he learned in Lublin about the extermination of the Jews, Morgen visited concentration camp Auschwitz. The occasion for his investigation was a parcel which had been confiscated by customs. A member of the staff had sent it from Auschwitz to his spouse in Germany. The parcel would never reach its destination however as it was opened for inspection by customs who found chunks of gold in it. It was confiscated as contraband and it was reported to the SS und Polizeigericht. This is how Morgen, who had been promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer on November 9, 1943 got involved in the case. He established that the gold had come from fillings of the teeth of prisoners and he traveled to Auschwitz to investigate further.

The investigation that was launched by Konrad Morgen in Auschwitz was at least comparable in scope to the big corruption case in Buchenwald. For some six months research was conducted into evidence of theft and other crimes committed by staff members. After the war, Morgen stated that "the conduct of SS personnel [in Auschwitz] didn’t, in any way, meet the standards one might expect from soldiers. They made the impression of demoralized, bestialized parasites."[5] According to SS judge Helmut Bartsch, a member of Morgen’s team, between October 1943 and his departure from the camp in April 1944, 123 investigations were launched into SS personnel in Auschwitz. "Based on the results," he declared, "twenty-three lower and two higher ranking SS men were arrested." The verdicts varied between two and four years imprisonment and "in most cases, the convicts were discharged from the Waffen-SS."[6]

One of the higher ranking SS men named by Bartsch was probably SS-Untersturmführer Maximilian Grabner. He and his associate, SS-Oberscharführer Wilhelm Boger were charged with ‘illegal’ murder by Morgen. Both men worked in the political department of Auschwitz, also known as the camp Gestapo. Morgen and his colleagues failed however to bring Boger to court. He remained active in the camp until its evacuation in January 1945. They did manage however to open a case against Grabner. The hearing took place in Weimar in October 1944. Chairman of the court was Dr. Werner Hansen. He stated later that Grabner had been indicted for the murder of 2,000 inmates who had allegedly been shot in order to make room in the overcrowded prison in Auschwitz. The prosecution demanded twelve years imprisonment but the case was postponed in order to investigate the question whether orders for the executions had been issued by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA). As Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller obstructed this, the investigation bogged down. In the end, Grabner returned to Katowice as a Gestapo agent where he had worked before his posting to Auschwitz.

Maximilian Grabner, the leader of the political department at Auschwitz. Morgen accused him of illegal killings. Source: Auschwitz Memorial

Indications exist that Morgen’s investigative team in Auschwitz was also thwarted. Both Morgen and his colleague Wilhelm Reimers reported that one night the wooden barracks, in which they had stored their evidence, went up in flames. After the war, Morgen voiced his suspicion that the arson had been a part of a plot, orchestrated from higher up with Oswald Pohl as the sinister brain behind it. According to him, Pohl not only protected his corrupt personnel in the concentration camps, but he was corrupt himself as well. Together with his closest colleagues, he would have had gold from the camp melted down and the revenue deposited in an account. This way he could have channeled away hundreds of thousands of Reichsmark.

Morgen has also attempted to prosecute Rudolph Höss, camp commander of Auschwitz until late 1943. Morgen had discovered that Höss had had a secret relationship with a female inmate in Auschwitz. Her name was Eleonore Hodys, a physician born in Vienna in 1903. Being a political prisoner, she was put to work as a seamstress in the villa of Höss where she held a privileged position. Probably because his wife suspected something was going on between her husband and Hodys, she was fired. She ended up in the camp prison where the camp commander paid her regular visits in secret. When she became pregnant by him, the relationship was over and her privileged position came to an end. As he said himself, Morgen liberated her from the prison and saw to her release from Auschwitz. It is unclear whether it happened this way, but in the spring of 1944 he interrogated her in a hospital in Munich. This hearing didn’t lead to Höss’ prosecution.

Last year of the war

Historians have claimed that in April 1944, Himmler ordered Morgen to occupy himself only with the case against Koch. Himmler would have done so in order to prevent Morgen from prosecuting Höss and other high ranking participants in the elimination of the Jews and in so doing thwart the extermination program. There was no question of this however. Günther Reinecke, chief of the SS und Poliezeihauptgericht testified during the Nuremberg trials that although Himmler had ordered Morgen to limit himself to the case against Koch, Franz Breithaupt, chief of the Hauptamt SS-Gericht, had successfully protested against this. In a letter dated August 26, 1944 to Breithaupt from Franz Bender, the Oberste SS- und Polizeirichter (chief judge), part of the staff of the Reichsführer-SS, Himmler’s compliments were forwarded to Morgen for his "good work done in the concentration camps."[7] Himmler issued the order for Morgen’s promotion to SS-Sturmbannführer in the Waffen-SS, which followed on November 9, 1944.

Little is known about Morgen’s activities at the turn of 1944, but his investigations in the concentration camps seemed to have stopped altogether. In the fall of 1944, Morgen was appointed chief SS judge in Krakow. He only dealt with routine legal cases and felt he had been "side tracked."[8] On January 19, 1945, Krakow was captured by the Red Army. Morgen meanwhile had been transferred to Breslau, today Wroclaw.

At the end of war, Morgen was kept in Soviet and Czech custody as a prisoner-of-war for a short while. After his release, he reported to the Western Allies on his own initiative after he had learned he was wanted for his "knowledge of concentration camps."[9] On September 22, 1945 he arrived from Prien in Bavaria at the headquarters of the American Counterintelligence Corps of the 7th Armyin Mannheim. This was the beginning of Morgen’s role in various trials against war criminals, which would take place in the following years. Apart from being a witness he was a defendant as well, due to his position in the SS. After having been transferred to CIC headquarters in Oberursel in Hessen for interrogation, he was transferred to former concentration camp Dachau as a suspect. The camp was now in use by the Americans as a detention camp for Germans, suspected of war crimes.

In Dachau, the Americans also held trials against Nazi war criminals. One of them was Ilse Koch. The wife of the camp commander of Buchenwald was indicted by the Americans for the most horrible crimes. The charge that she had a lamp shade made of human skin, was the focal point of the prosecutors. In order to prove this, the Americans allegedly would have attempted to have Morgen sign a declaration, confirming the charge against Ilse Koch as to the lamp shade. Although he had established the sadistic nature of the woman in the course of his own investigation and the rumors about the lamp shade were already circulating, a thorough search of the house, conducted by him, hadn’t yielded a single shred of evidence. As much as he loathed the sadistic nature of the wife of the camp commander, he refused to sign the declaration.

Ilse Koch on August 14, 1947 during the trial of her at Dachau. Morgen refused to give false testimony against her. Source: U.S. National Archives

Definitielijst

- Buchenwald

- Concentration camp established in 1937 near the city of Weimar.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Dachau

- City in the German state of Bavaria where the Nazis established their first concentration camp.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Majdanek

- Concentration camp nearby the Polish city of Lublin. Originally a POW camp. From 1942 an extermination camp.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nuremberg trials

- Trials in 1946 of an allied military tribunal against the most important representatives of the Nazi regime. They stood trial as war criminals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

After the war

Nuremberg

During the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg (IMT), Konrad Morgen was called as a witness on August 7 and 8, 1946, by dr. Horst Pelckmann, counsel of the SS. Although the Tribunal was inundated by the enormous mass of incriminating evidence against the SS, Morgen testimony was to reset its image as a criminal organization. It was the intention of the defense to present Morgen’s investigation into torture and illegal murders in the concentration camps as proof for the thesis that misdemeanors were not allowed within the SS and should be attributed to criminal individuals. Morgen’s story had no positive influence on the defense of the SS. The prosecutors considered his testimony so little convincing, they didn't even want to cross-examine him.

Konrad Morgen as a witness at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. Source: U.S. National Archives

In Nuremberg, Morgen also appeared as a witness during the trial before the Nuremberg Military Tribunal (NMT) against Oswald Pohl and seventeen of his associates within the SS-WVHA, that took place between April 8 and November, 1947. On August 21 and 22, Morgen was called as a witness for the defense. His testimony should show again that the conditions in the concentration camps weren’t as bad as presented. Again, Morgen’s testimony was received with distrust. Pohl was pronounced guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity and membership of a criminal organization. He was sentenced by hanging and the verdict was executed on June 7, 1951.

Oswald Pohl in the dock at the U.S. military tribunal in Nuremberg. Morgen was called as a witness during his trial. Source: U.S. National Archives

Denazification

On January 28, 1946, Morgen was taken into political detention himself in Internierungslager Ludwigsburg. Due to his membership of the NSDAP and high rank in the SS, he was subjected to a process of Denazification. The trial began on June 24, 1948. Morgen defended himself with gusto: he declared to have become a lawyer ‘to serve justice’ and told the court he had fought against ‘crimes against humanity.’ Based on his resistance against the crimes in the concentration camps and the risks he ran in the process, the court decided to consider him a so-called Entlastete (innocent). Thereafter Morgen was a free man and the cost of the trial was the responsibility of the state.

In 1950, Morgen was called to account for himself again before a Spruchkammer, this time in Nord-Württemberg. The Ministry of Political Liberation in the Federal Republic of Germany had called for a revision of the earlier verdict as it was presumed that "in the conduct of defendant, there is no question of active resistance against the National socialist dictatorship."[10] The court passed its verdict on November 27, 1950. This time he wasn’t categorized as Entlastete, but was considered Mitläufer (fellow traveler). In practice, this made little difference as, pursuant to new legislation, no legal distinction was made anymore between the less guilty, the fellow travelers and the innocent.

The Auschwitz trial

After his Denazification processes had come to an end, Morgen resumed his pre-war career. He became an attorney in Frankfurt am Main; from May 16 1951, until January 19, 1979, he was a member of the Rechtsanwaltskammer (bar association). In this period he appeared as a witness again during a trial against war criminals: the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt that took place from December 1, 1963 to August 10, 1965. Whereas Morgen’s testimony had been rejected in Nuremberg, in Frankfurt it played an important role. He could explain to the court what in concentration camps was a crime and what not, pursuant to Nazi legislation. He emphasized that the gassing of Jews was simply carrying out orders, but in the camps executions also took place for which no official orders had been issued but these were carried out on personal initiative. Partly due to the information given by Morgen, it could be proved that camp guards Wilhelm Boger and Joseph Klehr had been guilty on individual grounds of various murders; they were sentenced to life imprisonment.

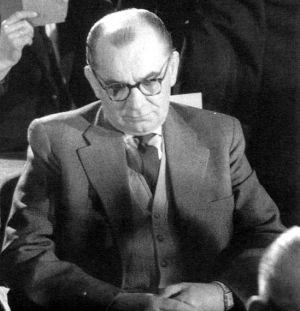

Josef Klehr as a defendant during the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt. Morgen was also called as a witness during this trial. Source: H.E.A.R.T.

Penal cases

After the war, Morgen not only had to deal with the courts as witness or attorney, but also as a suspect. The Landesgericht in Frankfurt am Main opened no less than three preliminary investigations against him. Involved were charges in connection with two alleged crimes Morgen would have been guilty of during the war. The first preliminary investigation took place in 1955. He was charged with having drafted an appeal in Budapest in 1944, during the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, in which he had comforted the Jews by saying that nothing would happen to them in Germany. Moreover he would have urged them not to hand over their possessions to the Hungarian police. Morgen admitted he had been in Budapest at the time for two days in order to interrogate Adolf Eichmann, the organizer of the deportation of the Hungarian Jews. However, he contradicted the charge he had drafted an appeal with such a message himself. Morgen was acquitted for lack of evidence. In 1972 he was indicted on the same count but again without any result. New evidence wasn’t found.

The other investigation against Morgen took place in 1961. He was charged at the time with having been involved with the death of four Russian prisoners-of-war after a medical experiment in camp Buchenwald in 1943. The occasion for this experiment had been the death of camp guard Köhler. Morgen assumed that guard Köhler had been poisoned by camp physician Hoven on orders from commander Koch to prevent Köhler from testifying against him. In order to establish what he had been poisoned with, in the presence of Morgen, four Russian prisoners-of-war, who had been sentenced to death, were administered toxic substances which had been at Hoven’s disposal, only to see how they would react. They survived the experiment but were executed nevertheless. No evidence was found that Morgen "had been involved in whichever way in the murder of the guinea pigs later on," neither was there any indication that he "had given the order to conduct the experiment."[11] Therefore, the Landesgericht acquitted him.

Konrad Morgen during his interview for the British documentary series The World at War. Source: H.E.A.R.T.

In the seventies, Morgen was interviewed by American historian John Toland and for the British documentary series The World at War. He passed away on February 4, 1982 at the age of seventy-two.

Notes

- Morgen, K., Wesentliches Ermittlungergebnis, Harvard Law School Library, p. 60

- Personal file Hermann Florstedt, Das Bundesarchiv

- Lidner, P., 'Überlebte Hermann Florstedt den Zweiten Weltkrieg?', Zeitschrift für Heimatforschung, 10, 2001, p. 81

- IMT Nuremberg, Interrogation Konrad Morgen, 7 August 1946

- Rees, L., Auschwitz, pp. 200-201.

- Langbein, H. People in Auschwitz, p. 299

- Personal file Konrad Morgen, Bundesarchiv

- Denazification Ludwigsburg 1948, EL 90313, Bü2196, Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg

- IMT Nuremberg, interogation Konrad Morgen, 8 August 1946

- Denazification Ludwigsburg 1948, EL 90313, Bü2196, Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg

- Ermittlungsverfahren gegen Konrad Morgen, 29 March 1961, Abt./Nr. 461 / 303942, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv

Definitielijst

- crimes against humanity

- Term that was introduced during the Nuremburg Trials. Crimes against humanity are inhuman treatment against civilian population and persecution on the basis of race or political or religious beliefs.

- Denazification

- Post war policy of the allies in Germany to punish Nazi war criminals and to remove known Nazis from positions of power or public service.

- dictatorship

- A form of government where the power in a country is in the hands of one person, the dictator. Originally a Roman regime in case of an emergency where total power would rest with one person during six months in order to face a crisis.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Last edit on:

- 25-10-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

News

Illegal murders in Auschwitz

WWII specialist Kevin Prenger wrote: 'A Judge in Auschwitz' about SS judge Konrad Morgen. In 1943, this judge paid a visit to concentration camp Auschwitz in order to investigate malpractices in the camp – as strange as it may sound. The occasion was a parcel, sent from the camp and containing chunks of gold and which was intercepted by customs. In the camp, Morgen discovered this smuggling affair was the tip of an iceberg: camp guards in their masses were guilty of theft and corruption. Whereas in the gas chambers of Nazi-Germany millions of Jews are being killed, Morgen is engaged in gathering evidence of 'illegal' murders. The Dutch History website Historiek.net questioned author Kevin Prenger about his remarkable book.

New book about SS Judge Konrad Morgen published

In October 2021 Pen & Sword Books published a book written by TracesOfWar volunteer Kevin Prenger. It is titled A Judge in Auschwitz and tells about Konrad Morgen's crusade against SS corruption & 'illegal' murder in the concentration camps. It has already been published successfully in Dutch and Polish. This English version was translated by Arnold W. Palthe, also a contributor of this website.