Introduction

A tree with a nameplate in Jerusalem is one of the few tangible memories of Austrian Julius Madritsch. In 1964, Yad Vashem nominated him Righteous among the nations. As a factory owner in Poland, he managed to save the lives of a part of his Jewish employees. He did this in cooperation with his much better-known colleague Oskar Schindler, whose story was filmed by Steven Spielberg under the name ‘Schindler’s List’ in 1993.

Definitielijst

- Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem is Israel’s national Holocaust memorial where in addition to Jewish victims and resistance heroes, also non-Jewish helpers of Jews during the World War 2 are being honoured. Those non-Jewish are called the Righteous Among The Nations. Until the mid 90’s trees were planted for these rescuers. In 1996 a special remembrance garden was established displaying all of the names of the helpers. Every year new names are added.

Treuhändler / Authorized representative

Julius Madritsch was born on January 4, 1906 in Vienna. In that city he followed training in textile production. From the end of 1938, he worked as an independent textile producer and textile wholesaler. On March 13, 1938, Germany annexed his motherland during the so-called Anschluss (connection). It happened without armed deployment as a large part of the Austrian population, strongly oriented towards Germany, welcomed the annexation. In many places in Austria, ecstatic crowds, gathered along the streets and, welcomed the invading German army with their tanks and other military vehicles. For Madritsch, the annexation meant being called-up for military service in the Wehrmacht in 1940. He managed to dodge this draft because he received an order to produce shirts for the German Army, which made him significant for the war effort. After the war, he apologized that it was not out of cowardice that he dodged military service. He claimed to have already been an opponent of the Nazi regime and to have refused to serve in their army. However, from 1940, he would be employed as a civilian in the western part of Poland, which had been conquered by the German army in September 1939. Like Oskar Schindler, he saw opportunities for commercial success there. Labour and production costs were low, and companies that formerly belonged to Poland were taken over at low costs. Poles were considered inferior. In the future, they would only be allowed to serve as cheap labour in the German Empire.

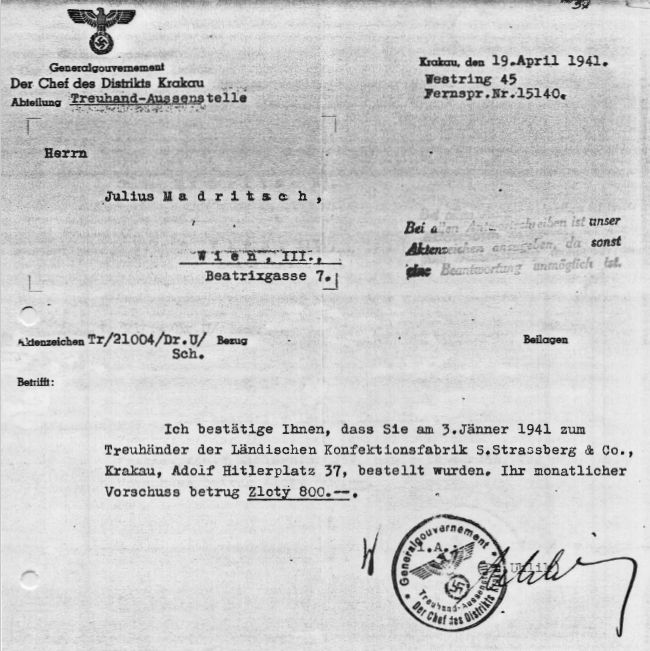

With the help of a business aquaintance, Julius Madritsch found a job as supervisor in a textile company in Kraków, taken over by the Germans. Shortly after, the German authorities appointed him as a so-called Treuhändler [trustee] for two clothing companies in the same town. A Treuhändler was an authorized representative or supervisor, appointed as a replacement of the original (Jewish) manager of a company, that had been confiscated by the Germans. Both companies employed Jewish as well as Polish workers. Madritsch claimed to have heard of the bad treatment they received from the German civil administration, the SS and the German police. Kraków was named by the Germans as the capital of the so-called Generalgouvernement in central Poland. It was the seat of the German governor, Hans Frank, a prominent Nazi lawyer, who was guilty in Poland of exorbitant self-enrichment and ruthless suppression. From October 1939 on, Jewish people had to report for forced labour. In November a Jewish counsel was established and starting that same month Jews were obliged to wear a white armband with a blue star of David.

Confirmation of the appointment of Julius Madritsch as Treuhänder of a clothing company in Kraków. Source: Österreichische Gesellschaft für Zeitgeschichte

It was the wish of the German occupation administration to make the capital of the Generalgouvernement free of Jews. In May 1940, they began to expel the Jews to cities in the neighboring area. Approximately 55.000 Jews had already left the city in March 1941. About 15.000 remained. These remaining Jews, together with "evacuated" Jews from surrounding towns, were forced that May to move to a ghetto in the south of Kraków, situated in the original Jewish district. Between 15.000 and 20.000 Jews had to live within an area closed off by walls and barbed wire fences and separated from the rest of the city. Hunger was rife and as a result of overcrowding, many Jews had to live on the street. Those employed were generally better of than the rest. They found employment in various factories inside and outside the ghetto. Best known is the Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik (DAF). In 1939, Oskar Schindler took over this production facility from the original Jewish owners for a pittance In this factory, he employed mainly Jews, because they were cheap labour. Schindler’s Jewish personnel could count on decent treatment and no deportation.

In the two factories in the vicinity of the ghetto that Madritsch supervised, labour conditions for Madritsch’s Jewish employees were also good. He financed the care of his employees by selling saved pieces of fabric on the black market. His companies were considered Kriegswichtig (significant for warfare), which protected his Jewish employees against persecution. Nevertheless, after the establishment of the ghetto, it took Madritsch’s great effort to defend the interests of his Jewish labourers against the SS and the labour office of the Generalgouvernement. He was supposed to employ non-Jewish Poles instead of Jews. The authorities upbraided him for sabotaging the German policy concerning the Jews. In his memoirs, Madritsch claimed to have received threats that his actions would bring him into conflict with the Gestapo. But these threats did not deter him from hiring more and more Jewish employees. However, his responsibility for two factories came to an end when the German occupation administration decided that, from then on, only war wounded were allowed to function as Treuhändler, so that healthy men like Madritsch could still be called up for service in the Wehrmacht. This time, Madritsch could not dodge the military service; so at the end of April 1941, he joined the Wehrmacht. In his own words, leaving Kraków was a heavy blow, since he could not care any longer for the people he had been able to protect.

Regarding his time in the Wehrmacht, Madritzsch claimed that he was not of much use to them. "From the first day on, I had sworn that I would not fight for this system, that brought only suffering and sorrow over the whole of Europe",[1] he wrote in his memoirs. Instead of serving at the front, he had been given an office function in the Wehrkreiskommando XVII in Vienna. His former position as a Treuhänder in Kraków was initially taken over by an SA officer, who was said to have conducted a reign of terror in the factories. Madritsch was therefore glad when the man was replaced by Heinz Bayer who, just like himself, was a Viennese and no fanatical Nazi. Earlier, Madritsch received permission from the administration of the Generalgouvernement to start his own company but had been compelled to postpone this intention indefinitely, due to his entry into the army. However, when Bayer visited him one day in Vienna, Madritsch decided, to try to start his own business after all. He managed to get a leave of absence a couple of times in order to start a clothing company with Bayer as manager. The factory was established within the ghetto. At the request of the Jewish council, Jewish employees were hired.

Around the time that Madritsch started his factory, the persecution of the Polish Jews had taken a disastrous turn. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, mainly Soviet Jews had been the target of genocide. In 1942 the extermination of the Jews started also in the other German occupied territories in Europe. During the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on January 20, 1942, representatives from the concerned authorities, were informed of the intention to exterminate 11 million Jews. According to Nazi statistics, 2.284.000 of them were already within the boundaries of the Generalgouvernement. To facilitate this extermination, Aktion Reinhart was put in action by Odilo Globocnik, chief of the SS and police in the Lublin district. Differing from the approach from behind the eastern front, where Jews were killed by firing squads of the Einsatzgruppen, most of the Jews from the rest of Europe would be killed in the gas chambers of the extermination camps in Poland. Others would perish from exhaustion and illness in the labour camps. The three extermination camps that were established as part of Action Reinhart were situated in eastern Poland, in Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka, where the first transports arrived respectively in March, May and July of 1942.

From the Kraków ghetto, the first deportations for the purpose of murder were to the Auschwitz concentration camp on March 23-24: 50 Jewish intellectuals were deported and murdered there. A much larger deportation took place at the beginning of June of the same year. On May 28 the ghetto with around 17.000 registered Jews was locked down. During the days following, house searches took place and Jews without a valid labour stamp on their ID were arrested and deported. Between June 2 and 8, a total of 7.000 Jews were deported. The rumour was that they were sent to labour camps in the Ukraine, but their real destination was Belzec, where they were gassed immediately upon arrival. Although Madritsch’s employees and their kin were safeguarded from deportation, one of his labourers lost his wife and children during the German actions and another her husband.

Heinz Bayer, Madritsch’s righthand man, was confronted with the deportations from up close. As a consequence, he became overstressed and in addition suffered persistent eye problems. He became incapacitated and returned to Vienna. In August 1942, Madritsch then took over the daily management of the factory. Officially Madritsch was still in the service of the Wehrmacht, but at various times he was given leave to consult with his manager in Kraków with his manager, Raimund Titsch in Kraków. In November 1942, Madritsch was relieved of the service in the Wehrmacht, which enabled him to devote himself entirely to the management of the factory. After the war, he claimed that he was discharged because his superiors did not have a very high opinion of his "capacities as a soldier". The real reason presumably was, that he was of greater value for the German war effort as manager of a factory that served war production than as an official in Vienna. Thanks to his useful contacts with the Textile Department of the Chamber of Commerce in Kraków, Madritsch was able to secure a lucrative order to produce uniforms for the Wehrmacht.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

A safe refuge

Aided by Raimund Titsch and other non-Jewish employees from Poland and Austria, Madritsch succeeded in turning his factory into a haven for his Jewish labourers and their families. The same applied to the clothing factory he opened, a short time later, in Tarnów in the south of Poland, near the local ghetto. Both factories employed around 800 labourers, most of whom were Jewish. In the ghetto of Bochnia also, a town approximately 45 kilometres east of Kraków, Madritsch started a factory with Jewish employees. Although the SS aimed at the total extermination of the Jews, in many places some Jews, who were fit for work, were left alive for the time being to work for the benefit of the German war industry, which was struggling with serious personnel shortages. For the employment of Jewish labourers, approval had to be granted by the SS and the Ministry of Armament and Munitions in Berlin. This approval was granted to Madritsch. Since spouses and children of Jewish labourers were in principle also safeguarded from deportation, the number of his protégés was larger than the total number of Jewish employees in his service. For the use of these Jewish labourers, he paid the SS an amount of probably 4 zloty a day for men and 2,4 for women.

In the factory in Kraków, as well as those in Tarnów, Madritsch had access to 300 sewing machines. As usual, they were old models with foot drive, which did not meet quality demands. In consultation with the Jewish council, Madritsch decided to employ two or three workers per sewing machine even though one worker was enough. In this way, he was able to provide deportation exemptions for more employees. Only 40% of his employees had been trained for this work. The remainder had never worked in the textile industry and often were not accustomed to working with their hands. For example, they were doctors, lawyers, engineers and entrepreneurs. Only 40% of his employees were responsible for 100% of production. Of this production, according to Madritsch 95% was meant for the civilian sector, the remainder for the military.

The shrewd entrepreneur managed to win simple assignments that required little material and yielded a lot of profit. He managed to keep these facts hidden thanks to the cooperation of German officials, whom he bribed with money and gifts. A great help for Madritsch was Artur Missbach, the leader of the Economical Bureau for the Textile and Clothing industry in the Generalgouvernement. This bureaucrat, who joined the NSDAP in 1931 and who, after the war, would occupy a seat in the Bundestag on behalf of the Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU), managed to manipulate Madritsch’s reports in such a way that they met the demands of the Rüstungsinspektion, the department in the Ministry of Armament and Munitions that controlled production for the army.

In addition to saving his Jewish employees from deportation by giving them work, Madritsch, took care to make sure that their living conditions were better than those of their fellow workers elsewhere. In Nazi labour camps, maltreatment of prisoners was the custom. However, working conditions in Madritsch’s factories were humane. Jewish workers were allowed to have contact with Poles from outside the factory to whom they could trust their possessions and they received additional food on top of their meager rations. In Madritsch’s factories, kosher kitchens were set up and Madritsch and his manager Titsch, provided extra bread that their employees could take to the ghetto to distribute among other family members and other people in need. By making sewing material available to other workshops with Jewish prisoners, Madritsch managed to help more people than merely those who worked in his own factories.

An important helper in the rescue work of Madritsch and Titsch was Oswald Bosko, also Austria-born. Before the war, he had been a waiter in Vienna, but now, he served as a Feldwebel (sergeant) in the German police in Podgórze, the Kraków district of which the ghetto was a part. He was the son of an Austrian official and had studied at a seminary. A life in the service of God was not reserved for him and after he left the monastery he became a member of the Austrian branch of the Nazi party. After the NSDAP was banned in 1933, he joined an underground section of the SS, which opposed the Austrian authorities. After the Anschluss of Austria to Germany in 1938, he made, in his own words, a remarkable turn and claimed to have become an opponent of the Nazis. He nevertheless joined the Schutzpolizei, the uniformed police that was involved in guarding the ghettos and carrying out raids in Poland.

Bosko came to Kraków in the summer of 1942. As a ghetto guard, he made sure not to attract attention by treating the ghetto residents too humanely. So he shouted abuse at them just like the others. This behaviour, however, concealed the fact that he cared about the Jews. He smuggled foodstuffs into the ghetto and aided Jews to escape from the ghetto and go into hiding with Christian Polish citizens. His help, however, was not entirely without self-interest, for he accepted bribes. Among the Jews who were smuggled out of the ghetto by Bosko, were some associates of Madritsch. Madritsch and Titsch received help from several other police officers in their organising of escapes. The officers were responsible for the counting of the labourers at the beginning and end of their working day and ignored it when labourers were missing. Madritch likely had to bribe them for this.

Definitielijst

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

End of the ghettos

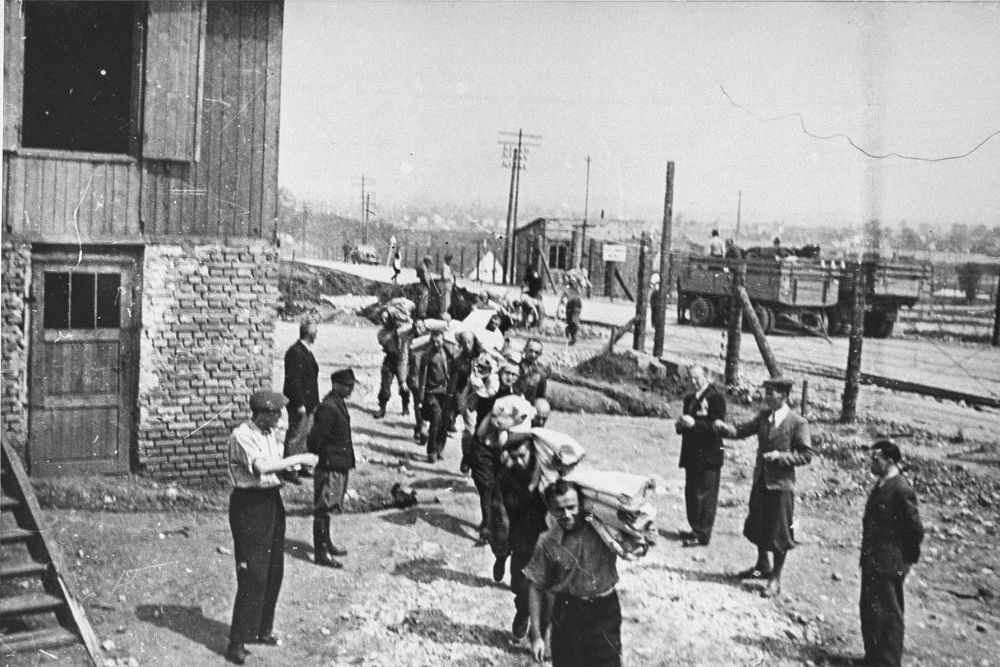

After the transports of June 1942, on October 28, 1942, more Jews were deported from the Kraków ghetto and murdered: between 6.000 and 7.000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz and Belzec. In addition, about 700 were shot within the ghetto. After this, the ghetto was reduced in size and divided in two: one part for the working Jews, including the employees of Madritsch, and the other part for the others. On March 13 and 14, 1943, the ghetto was liquidated. Luggage left in the street formed the silent evidence of what took place. Around 1.000 Jews, living in the ghetto were executed on the spot and another 3.000 were transported in cattle wagons to Auschwitz, where many were killed on arrival in the gas chamber. However, approximately 2.000 Jews were spared, among whom were those with work, functionaries of the Jewish council and members of the Jewish police (the Ordnungsdienst). They were transferred to labour camp Plaszów, located a few kilometres from the Kraków centre. The last metres to the camp led them over a lugubrious path, paved with gravestones from the desecrated Jewish cemetery.

Most of the Jews, who were fit for work had already been transferred from the Kraków ghetto to Plaszów in December 1942, but Madritsch had managed to keep his employees in the ghetto until March 13. There, he considered them better protected against the winter conditions, because the barracks in the camp were not yet available. The washing facilities also needed to be constructed. Madritsch himself had seen the living conditions in the camp. He was also witness to the heavy labour, the prisoners had to perform. In his memoirs, he expressed his horror at how women of all ages and social backgrounds in the icy cold and their feet wrapped in jute bags had to push loaded lorries in the nearby quarry. Since his employees, after the liquidation of the ghetto, were still housed in Plaszów, they continued working in the Madritsch factory in Kraków till September 1943. Every morning they went on foot from the camp to the factory and returned on foot at the end of the day. In February 1943, Madritsch had received permission for this after consultation with the responsible authorities. He also had received permission to let his employees perform night shifts outside the camp. In his factory, they were temporarily protected against the severe camp regime.

During the March 1943 deportations from the Kraków ghetto, Madritsch stood up for his Jewish employees. When he learned that the Nazis planned to deport all young children from the ghetto, he decided to save at least the children of his employees. A decisive role in this rescue operation was given to the Viennese policeman Oswald Bosko. In the dead of the night, Bosko transferred parents and children from the heavily guarded ghetto to Madritsch’s factory outside the ghetto. The smallest of the children were transported in rucksacks and were given an opiate so that they could not betray the operation. Since the refugees could not stay in the factory, they were then housed with helpful Christian Polish families. In his memoirs, Madritsch pointed out that the rescue operation had been supported also by some soldiers from the Wehrmacht, who transported the Jewish refugees with a lorry to Tarnów, where they were safe for the time being. In the following days, the remaining children in Kraków were deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz or, were murdered with their mothers in the Jewish cemetery in Kraków. During the days after the deportations, some of the Jews who were hiding in the ghetto, found temporary shelter in Madritsch’s factory, with the help of Bosko.

Madritsch also managed to obtain permission to transfer some of his employees from Plaszów to Tarnów to assist in the production of winter coats for the army on the east front. Particularly for his older employees the daily 45-minute march from Plaszów to his factory in Kraków and back was a torment. According to Madritsch, the circumstances in Tarnów made it more of an oasis, compared to Plaszów. After all, the Jews in the Tarnów ghetto lived in ordinary houses with beds of their own. Possibly, Madritsch had to bribe Amon Göth, the camp commander of Plaszów, for permission for the transfer. Anyway, because they were needed for "a very urgent defence mission", 232 men, women and children, were on March 25 and 26, 1943, transferred without SS-guards, by train from Kraków to Tarnów. Raimund Titsch and a colleague accompanied the transport, together with some private security guards. In Tarnów they would be safe for the time being.

After November 1942, when about 2,500 Jews were deported to Belzec, the Tarnów ghetto would continue to exist for about another year, until the Germans decided to liquidate it in September 1943. The transports to the Belzec and Treblinka extermination camps had already stopped, in December 1942 and February 1943 respectively. After the mass graves had been emptied by digging up the corpses and then incinerating them in big pits, both camps were closed and obliterated from the face of the earth. In Sobibor, another 19 transports from The Netherlands had arrived, during the spring and summer of 1943. However, after an uprising among the inmates of the camp in October 1943, this extermination camp also was closed. An estimated 1,7 million Jews, mostly from the Generalgouvernement, and an unknown number of Roma and Sinti were murdered in the three extermination camps during Aktion Reinhard. In the autumn of 1943, between 42.000 and 45.000 Jews remained in the Lublin district: they had been kept alive for the time being because they worked for the Wehrmacht. They were housed in labour camps. But at the beginning of November 1943, the majority of them were killed during the murder operation, called Aktion Erntefest (Operation Harvest Festival). Next, the SS hermetically sealed off the remaining labour camps and then executed the remaining prisoners in groups. After this, hardly any Jews remained in the Lublin district.

The Jews in Tarnów, in the Kraków district, did not become victims of the Erntefest. Before the closure of the Tarnóv ghetto in September 1943, around 10.000 Jews still lived there. During the September evacuation, 7.000 to 8.000 of them were deported to Auschwitz to be murdered there. The evacuation of the ghetto took place under the leadership of Amon Göth. This SS officer, notorious for his sadism, had also been involved in the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto in March 1943. There, he shot Jews single-handedly and did the same during the evacuation of the Tarnów ghetto. The night, before the operation he invited Madritsch and Titsch to dine with him in Plaszów. He informed both entrepreneurs about the impending "evacuation" of the Jews in the Kraków-district and conveyed to them that the two Austrians were "his guests until tomorrow". Göth left them bewildered in the company of two SS officers. After the war, Madritsch remembered that the ensuing hours were "torture". He and Titsch were concerned about their people in Tarnow and Bochnia, but they could not allow their anxiety to become apparent.

The next day, Madritsch and Titsch regained their freedom. In the meantime, the evacuation of the ghetto had been concluded and Göth, who presumably knew of Madritsch’s good relations with the Jews, no longer had to fear that the industrialist would somehow thwart the operation. Immediately after his release, Madritsch drove to Tarnów and Bochnia to find out what had happened to his employees. He met Göth in the ghetto of Tarnów who assured him that his employees had not been harmed and that they would be transferred to the Plaszów labour camp. In his own words, Madritsch managed to help some Jews from the Tarnów ghetto to escape. These were Jews who were employed in a clean-up team. Madritsch offered 60 clean-up workers temporary shelter in his factory, and 10 of them were able to escape unnoticed to Slovakia. The fate of his employees in Bochnia remained unclear.

Definitielijst

- Aktion Erntefest

- “Operation Harvest Festival”. Code name for the German operation in the autumn of 1943 to exterminate all remaining Jews in the district of Lublin. It was a reaction to Jewish acts of resistance in the Generalgouvernement such as the uprisings in Sobibor and Treblinka. The operation started on 3 November 1943. Within a few days approximately 42,000 Jews were murdered.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- liquidate

- Annihilate, terminate, destroy.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Transfer to Plaszów

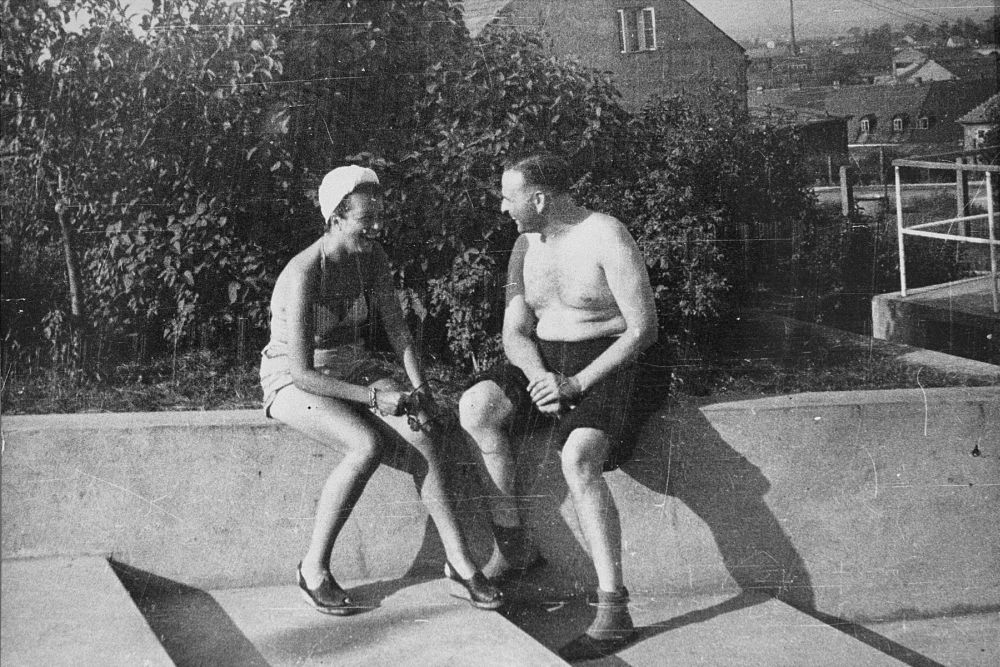

Bare-breasted, cigarette in his mouth and his rifle casually slung on his shoulder, that is how camp Plaszów commander Amon Góth was photographed. His fat belly is the result of all the parties in his villa, which often ended in orgies. Other pictures show his colossal Great Danes, which, it is said, were often allowed to sink their fangs in the flesh of defenceless prisoners. Former prisoners remembered how Göth, from his villa’s balcony that overlooked the campgrounds, shot at prisoners at random. With the same excessive violence with which he carried out the evacuation of the ghettos, he also ruled his camp. Göth was appointed camp commander on February 11, 1943, and would remain so until September 1944. The camp was founded as a labour camp in 1942 (Arbeitslager) and in January 1944 was turned into a concentration camp. In May 1944 it held approximately 24.000 inmates, the larger part coming mainly from the Kraków ghetto. Beatings, public hangings and heavy forced labour were part of Göth’s ruthless regime as camp commander.

Camp commander Amon Göth on the balcony of his villa near concentration camp Plaszów. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Leopold Page Photographic Collection

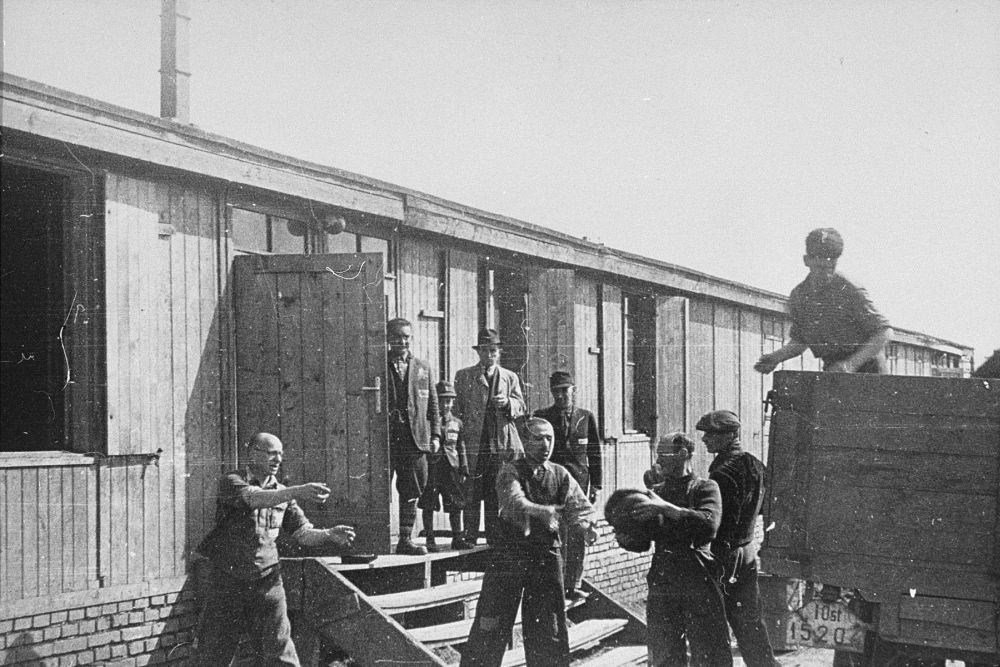

An estimated 8.000 people were murdered in Plaszów. Their corpses were buried in the mass graves outside the camp, in the same places as the victims who fell during the clearing of the Kraków ghetto. From September 1943, the moment that leaving the camp was no longer allowed, Madritsch had been compelled to move his sewing workshop to the industrial estate on the camp grounds, near Göth’s villa. With 2.000 to 3.000 employed prisoners, spread over 6 labour barracks, his sewing workshop was the largest one in Plaszów. From Kraków, Oskar Schindler transferred approximately 1.000 Jewish employees to Plaszów, where he housed them in a subcamp, Nebenlager Emalia, financed by himself.

Before moving their workshops to Plaszów, Madritsch and Titsch had to convince the SS of the importance of their production for the war effort. The SS had now taken charge of a large proportion of the war production in the Generalgouvernement, and it was difficult to convince Julian Schermer, the SS- and police chief of the Kraków district. After all, the policy, followed by the SS, was focused on the extermination of all Jews in the Generalgouvernement. According to Madritsch, his and Schindler’s successes in sparing the lives of their employees were mainly due to the mediation of Amon Göth. The camp commander would have done that, merely because Madritsch and he were fellow countrymen. Raimund Titsch spoke of a "Viennese understanding" because he and Madritsch and Göth together came from the Austrian capital. More likely, however is, that it took a lot of bribes. Madritsch did not reveal any of this in his memoirs. He reported only that at the height of his industrial activities in 1943-1944, he paid the SS 350.000 zloty a month for maintenance costs. Apart from that, he spent another monthly 250.000 zloty on other expenses.

Although his employees were not entirely safeguarded against the hardships of Camp Plaszów, Madritsch made every effort to make their stay in the camp as bearable as possible. His employees had no longer their factory kitchen and separate living quarters, but the workshop meant "neutral ground" for them, where they were protected against the excessive violence of Göth and his guards. Madritsch made sure that they received more food as a supplement to the very meagre camp rations. According to him, this involved a weekly portion of 6.000 loaves of bread and jam. He also provided for cigarettes. Much of this was acquired on the black market and part of this probably came from the SS warehouse in Plaszów. Except for food and cigarettes, Madritsch also provided his employees with clothing and footwear. Once, Madritsch received an order for the production of suspenders, whereby he was allowed to determine the required amount of leather. He secured a quantity of surplus leather and used that for the production of shoes for his employees who did not have shoes and walked on wooden clogs.

Holocaust survivor Margit Raab remarked in her memoirs that in Madritsch’s workshop in Plaszów, people worked in shifts: working parties worked alternately one week in the daytime and the other at night. According to Margit, "Madritsch’s workshop was one of the best places in Plaszów to work".[2] The more the employees of Madritsch produced, the more bread they received. Bread was not merely a supplement on meagre rations, but also a means of exchange for soap and various other items that were a luxury for the prisoners. Margit and her colleagues worked in parties of 5 and set up their assembly line for the production of military overalls. Every woman worked on a different part and it all came together at the end. This system did not always run smoothly, as sometimes the wrong parts were assembled or the parts did not fit properly. In that case, they stretched the pieces of fabric until they would fit. Once, they were caught: an overseer gently pulled on the overalls and they fell apart. Luckily, the overseer was a prisoner himself and the workers were not caught.

Although Madritsch was often away on business trips in Germany and Poland in consultation with the German authorities, he regularly visited his factory in Plaszów. He was there to convey his congratulations to his employees on Rosh Hasjana, the Jewish New Year. According to Margit, Madritsch was always kind and polite and he protected them against deportations.[3] He kept them day and night in the factory when selections were being held in the camp. Madritsch’s friendly and encouraging attitude towards his employees was a great help for his employees to sustain the hardships of their circumstances.

Good relations between Madritsch and Göth were essential for the maintenance of his factory and the protection of his employees. Unlike Schindler, who was on friendly terms with the camp commander and a frequent visitor to his parties, Madritsch’s relationship with Göth was strictly businesslike. Former inmates of Plaszów described Madritsch as a more moderate person than Schindler. According to Helen Sternlicht Rosenzweig, one of Göth’s two servants in Plaszów, unlike Schindler, Madritsch was not a womaniser and always kept a certain distance from Göth. She praised him for once bringing medicine for her sick mother. On the other hand, Raimond Titsch, Madritsch’s manager, did have a closer relationship with the camp commander. He was the one who made the above mentioned photographs of Góth. Various photographs show Göth in private, for example, sunbathing on a terrace with the wife of a colleague in a bathing suit. For unclear reasons, Titsch buried the film rolls in a box under the ground of a public garden in a Vienna suburb after the war. After digging them up again, he sold them in 1963 to an old employee of Oskar Schindler, after which they were developed and the world was given an image of the infamous commander and his camp.

Titsch and Göth often played a game of chess together. Since Göth was a bad loser, Titsch let him win every game. This way he could prevent the commander from exploding in fury and harming his prisoners. Once, during a lunch with Göth, Titsch, witnessed the latter taking a cook outside and shooting him behind his villa. The only thing the man had done wrong was to serve the soup too hot. The good relations between Titsch and Göth were, in Titsch’s case presumably, not due to sympathy but merely meant for the protection of Madritsch’s employees. Just like his boss, Titsch was also committed to their well-being in Plaszów. He helped them to make contact with Poles outside the camp, in particular with people who kept valuables for them. He also assisted them in receiving food parcels and passed on messages from the BBC radio about developments at the front, messages, passed onward by the prisoners themselves. He also managed to hire as a factory doctor a Jewish doctor, who was discharged from the camp hospital. If Göth had mistrusted Tisch or any disagreement between them had occurred, none of this would have been possible.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Schindler’s list

In January 1944, the Madritsch factory in Camp Plaszów was threatened with closure. On the night of January 8/9 Göth had been informed that the civilian enterprises in Plaszów were to be taken over by the Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke [German Equipment Factories], a production company run by the SS. Madritsch however advocated the continuation of his company activities in Plaszów. He relied on a contract, signed in September 1943 by the SS and the Kraków district police chief, that was valid until the end of the war. In February 1944 he received permission to continue his company activities for another six months, partly thanks to mediation of, among others, the textile department of the Chamber of Commerce in Kraków. Nonetheless, the factory was taken over by the Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke but that did not imply the end of Madritsch’s commitment. From then on, Madritsch was no longer considered executor, but a client. He had to pay a monthly 350.000 zloty to the Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke, and was responsible for the supply of materials and the distribution of manufactured goods. He was obliged to deliver 100.000 metres of fabric monthly and 1.300 prisoners were available for processing of these materials. He was also guaranteed that his employees would not be replaced by other prisoners.

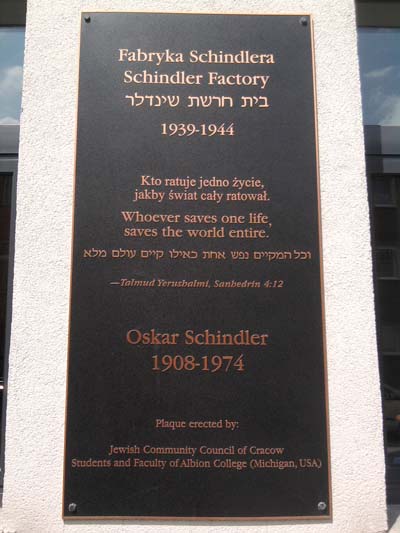

The takeover of Madritsch’s factory took place at a time when the downfall of the Third Reich was imminent. In the summer of 1944, an increasing number of German factories under the Generalgouvernement administration were dismantled and replaced in the West, as a result of the advancing Red Army. Madritsch too had his plans to continue his production in a safer area. He had a preference for the rural town of Drosendorf in Lower Austria, on the border with the Czech Republic. His plans to move failed because, in his own words, the crops in the fields where he had wanted to build his work- and living barracks had not yet been harvested. That is why he is presumed to have asked Oscar Schindler for help. Schindler had been ordered in August 1944 to dismantle his Nebenlager at Plaszów. He, however, was allowed to move his factory, thanks to bribes and good relations with important officials. With 1.000 Jewish prisoners (300 women and 700 men), in October 1944, Schindler managed to continue his business in Brněnec (Brünnlitz in German) in the Czech Republic in the Arbeitslager Brünnlitz, a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. His factory produced ammunition for the German army. Schindler personally made sure that his employees did not suffer any harm from the SS guards.

Of the 1.000 employees that were transferred to Brünnlitz, approximately a third of them had already been serving under Schindler before the move. Others got their place on the transport list presumably due to bribes. A good many of Schindler’s employees in Brünnlitz were prominent Jews from prewar Kraków or had been prison officials from camp Plaszów. Unlike the film "Schindler’s List", this transport list had not been drawn up by Schindler personally but by the actual compiler, Marcel Goldberg, the corrupt assistant of SS-Hauptscharführer Franz Josef Müller, who had succeeded Göth, suspected of corruption, as camp commander of Plaszów. Also, there happened to be not just one Schindler list, but several. Goldberg’s original lists are dated October 17, 1944, but those differ significantly from the lists of spring 1945. Many names from the original Goldberg lists had been deleted then and replaced by others. Moreover, besides the 1.000 Jews from Plaszów, some smaller transports arrived in Brünnlitz, which could also be added to the final list. This list, which is considered the "original" list by Yad Vashem dates from April 18, 1945, and contains the names of 801 men and 297 women. That is almost 100 more than the 1.000 Jewish employees in the beginning.

Fifty-three employees of Schindler in Brünnlitz were former employees of Madritsch. That is only a fraction of the 2000 Jewish workers who were previously employed by Madritsch. Schindler blamed Madritsch for not having managed to transfer more of his Jewish employees to Brünnlitz. According to Schindler, the "greedy" Madritsch had been more concerned about his sewing machines and textile supplies than "the fate of the people, entrusted to him".[4] During a party, Schindler maintained that he had suggested placing around 300 of his Jews on the list but that Madritsch had turned down this proposition and had called it "a lost cause". On the other hand, Schindler was full of praise for Raimund Titsch, Madritsch’s manager, who was also present at this party: Titsch would have been the true hero. He delivered the names of around 60 employees to put on the list, a number increased to 68 later on. It concerned the most important employees of Madritsch’s factory, including the foremen and their family members. In the end, 15 names would eventually be taken off the list, presumably because the corrupt Goldberg replaced them with Jews who paid him bribes.

After the war had ended, Madritsch himself however, stated that he had made an effort to transfer more of his employees to Brünnlitz, where they could have staffed a sewing workshop in Schindler’s factory. He had received permission for this from all responsible authorities except that of the department Arbeitseinsatz der Häftlinge of Amtsgruppe D of the SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt. Often, he travelled to Berlin to plead the case, but the SS refused to agree with the plan. Uniforms were no longer "indispensable production goods for the war effort".[5] After all, soldiers could fight in their civilian attire. The Jewish labour effort was reserved for munitions production. What also contributed to the failure of his efforts was that on the factory grounds where Schindler’s factory was situated, there was already an SS uniform workshop. That made Madritsch in August 1944 give up all hope. Gradually many of his former employees were deported to Auschwitz or the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. For the time being, he was allowed to keep 200 men and 300 women for cleaning up his factory site. On August 27 the demolition of the barracks started. The remaining labourers were removed: the men to Gross Rosen, the women to Auschwitz.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem is Israel’s national Holocaust memorial where in addition to Jewish victims and resistance heroes, also non-Jewish helpers of Jews during the World War 2 are being honoured. Those non-Jewish are called the Righteous Among The Nations. Until the mid 90’s trees were planted for these rescuers. In 1996 a special remembrance garden was established displaying all of the names of the helpers. Every year new names are added.

In the shadow

After the closure of his factory in Plaszów, Madritsch went to Vienna in September 1944 to see relatives. While he and his wife Charlotte were visiting his mother, her house was hit by a bomb. They were buried under the rubble but escaped unharmed. Madritsch returned to Kraków for the settlement of his affairs, where he was arrested by the Sicherheitsdienst and imprisoned in the infamous Montelupich prison. During the period 1940-1944, 50.000 prisoners, mostly Poles and Jews, were held here. Many of them were tortured or executed here by the Gestapo. From this prison, still in use today, Madritsch was transferred to the headquarters of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) in Berlin for 3 days. In his memoirs, he wrote that he was accused of the fact that his name occurred on a list of the Polish resistance and of spreading "horror stories about Plaszów." However, to his surprise, after 12 days of detention, he was released. Unfortunately, for one of his most important confederates things would turn out less well.

Oswald Bosko, the police officer who helped many Jews escape from the Kraków ghetto, stayed in Kraków until the summer of 1944. He is supposed to have injected himself with a disease to prevent his being sent to the Eastern Front. After a stay of some weeks in a hospital, he escaped, it seems, accompanied by two Jewish children and a Polish mistress. A suitcase full of unlawfully acquired goods from the ghetto was to provide for his maintenance. The Schutzpolizei initially assumed that their colleague was abducted by partisans. Bosko wrote a letter to his commander, in which he confirmed that he had indeed been kidnapped by partisans. However, his deception was discovered and he, disguised as a Polish farmer, was tracked down and arrested in the neighbourhood of Kraków. Just like Madritsch, he was imprisoned in the Montelupich prison. He was transferred from there to Danzig (today Gdansk) and subsequently sentenced to death by a German court marshall. His execution took place in the Gross Rosen concentration camp on September 18, 1944.

During that autumn Oscar Schindler also was arrested. He was interrogated in connection with the corruption investigation that the SS had started against Amon Göth, who was arrested in September 1944 but released due to health reasons and transferred to an SS sanatorium in the Bavarian Bad Tölz. There, in the spring of 1945, the Americans arrested the infamous camp commander Göth and transferred him to Poland. On September 5, 1946, the Polish supreme court sentenced him to death. In Kraków, September 13, 1946, they hanged him, not far from the infamous camp where, under his rule, approximately 5.000 Jews were murdered and many others humiliated, abused and traumatized for life. Before his execution, the war criminal unrepentantly gave a final salute to Adolf Hitler. Schindler, who was suspected of paying Göth bribes, was released by the Gestapo after eight days, presumably owing to his useful contacts within high circles of the German authorities. He went back to his factory in Brünnlitz, where his Jewish employees would be safe until the end of the war.

Because he was afraid of being arrested by the Soviets as a national socialist or capitalist, Schindler left Brünnlitz with his wife on May 9, 1945, at 5 minutes past midnight. Later that day, the Red Army would reach the factory. Disguised as prisoners, the Schindler couple safely reached the American occupation zone. Aided by support statements from his former Jewish employees, who testified to his good deeds, he did not have to go into hiding and was spared a denazification process. After a stay of some years in Germany, the couple emigrated to Argentina. Things did not go well for Oscar Schindler, neither in business nor personally. Business successes did not materialise and his marriage deteriorated. In 1958 he returned to Germany without his wife. Until he died in 1974, financial and health problems ruled his life. He drew strength from the support and friendship of the Jews whom he saved during the war and who honoured him. In 1962, he planted a tree in the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations in Jerusalem. It was not until 1993 that he was formally posthumously appointed Righteous Among the Nations, together with his wife Emilie who died in 2001.

Oskar Schindler with some of the Jews who survived the Second World War, due to his help. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Leopold Page Photographic Collection

With the release of "Schindler’s List" in 1993, the name Oskar Schindler became a household word. For the character Julius Madritsch, only an insignificant role was reserved. He would in no way reach the fame of Schindler. In all likelihood, this would not have bothered him at all, for according to Schindler researcher Robin O’Neil, he was very much attached to his privacy. After the war, Madritsch returned to Vienna, where he became owner of a textile company and co-owner of a hotel. He also represented several major German textile companies in Austria. His two sons, Gerhard and Gottfried, followed in their father’s footsteps. They were trained in the textile field and entered into their father‘s employ. Unlike Schindler, Madritsch was successful in business. He held various leadership positions in the union of the textile industry. As a representative of this industry, he was concerned with the issue of how the labour-intensive textile industry could survive in a time of increasing industrialisation. He also studied the consequences for the Austrian textile industry of Austria’s possible inclusion in the European Economic Community (the country only became a member of the European Union in 1995). For his services, Madritsch was awarded, the Silver Medal of Honour for Merit of the Republic of Austria.

On February 18, 1964, Julius Madritsch was awarded Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem at the same time as Raimund Titsch and Oswald Bosko. Madritsch’s nomination was not entirely undisputed. According to the granting demands, the Righteous should not have acquired any material gain in exchange for their help. Not only was Schindler convinced that Madritsch’ was driven by greed, but also at least one of his former Jewish employees, William Kornbluth was of that opinion. In his 1994 book "Sentenced to Remember", Kornbluth does not depict Madritsch favourably. Initially, Kornbluth was employed in the Madritsch factory in Tarnów. Although he admitted that his work in the factory saved him from deportation and, apart from that, he was able to smuggle food into the ghetto, he nonetheless complained that Madritsch did not pay him any money for his work. The circumstances in the factory were also not always favourable. Gestapo agents regularly visited the factory to try on suits, made for them by two Jewish foremen. During these visits they inspected the factory, searching for food and other contraband and often beating up the employees.

In particular one of Kornbluth’s accusations against Madritsch was quite malicious. Thanks to his job in the factory he escaped deportation in September 1942, but he claimed that Madritsch, at that time, agreed with the deportation of an unknown number of his female employees. That was "his contribution to the ovens of Auschwitch".[6] Kornbluth was surprised that no one had informed the Israeli government about this at the time of Madritsch’s recognition as Righteous. "His motives for running the factory were pure greed",[7] he claimed. According to him, Madritsch’s factory at Plaszów, where Kornbluth was employed, with a production of "20.000 military uniforms a month" was extremely profitable. Not Madritsch, but Raimund Titsch was the real hero, a "humane and decent man" who smuggled bread into the factory barracks. At the same time, Kornbluth admitted that Madritsch’s employees in Plaszów were better off compared with other prisoners. The work was less exhausting and took place indoors. Moreover, they benefited from the "unwritten rule that Madritsch’s employees were not to be executed".[8] However, they were not spared from all misery, the harsh camp regime was also applied to them and Kornbluth himself was beaten up several times by guards.

Schindler, as well as Kornbluth, considered Titsch as the real hero and depicted Madritsch as a businessman eager for financial gain. That is not correct. Schindler’s point of view is hypocritical because he is not entirely clean. In the late 1930s, he was active as a spy for the German Abwehr and played a role in the German annexation of the Sudetenland and the remainder of the Czech Republic. He was also involved in the preparation of the German invasion of Poland. In 1939, he became a member of the NSDAP. After the conquest of Poland, he used the opportunity to settle there as an entrepreneur because the economic climate was favourable. Labourers were cheap, and Jewish enterprises could be taken over cheaply. After the war, there was a reproach against him of unlawfully appropriating the factory inventory of a Jewish entrepreneur and even used violence in the process. These accusations were the reason for Yad Vashem not recognise him formally as Righteous, although his tree in the garden of the institute had been planted in 1962.

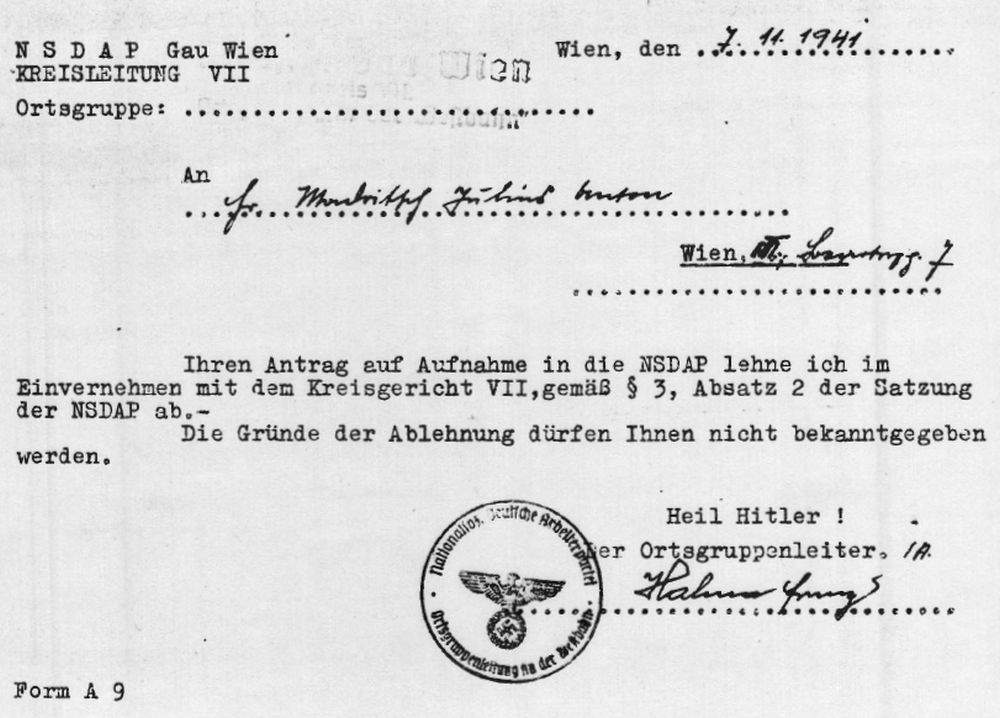

Madritsch also benefited from cheap Jewish labour in Poland and managed to get hold of Jewish property, but it is unlikely that he was ever a member of the NSDAP. He applied to become a member, but on September 7, 1941 he was denied without receiving any reason. Neither he nor Schindler were prosecuted by a denazification tribunal after the war. In 1948, the Austrian Volksgericht opened a preliminary investigation against Madritsch in the context of the persecution of Nazi-war crimes. He was accused of enriching himself improperly. During the preliminary investigation however, the case was dismissed.

Rejection for membership in the NSDAP sent to Julius Madretsch. Source: Österreichische Gesellschaft für Zeitgeschichte

Possibly, Schindler’s harsh judgment of his fellow entrepreneur arose from envy. After all, Madritsch did have successes in business after the war. Or maybe Schindler still resented that Madritsch made insufficient effort in transferring more of his Jewish employees to Brünnlitz. The reason for Kornbluth’s embittered judgment about Madritsch is not understandable. Without Madritsch, he presumably would not have survived the war. His accusation that Madritsch had placed Jewish female employees on transport to Auswitsch on his initiative does not fit in with the facts. On the contrary, Madritsch made all possible efforts to prevent his people from deportation. When some of his employees were allowed a transfer to Schindler’s factory in Brünnlitz, he had little influence over which employees were eligible and how many. Moreover, the accusation does not match the fact that Madritsch kept Jewish employees in his service until the last moment and that this took great effort. He might have met the wishes of the SS by replacing his Jewish employees with Christian Poles. That could have saved him a lot of time and trouble. He could have made more profit if he had replaced the surplus of unskilled Jewish labourers with Poles.

However, other former employees of Madritsch, including Margit Raab, praise him for his commitment during the war, their well-being and their survival. His Jewish employee Levinson-Page stated that he "was marvellous for his Jews".[9] Celina Karp Biniaz, whose parents worked for Madritsch, called him "more elegant and stylish than Schindler". According to her, he was a decent man with a warm heart.[10] She was equally full of praise about Raimund Titsch. Without his manager, Madritsch would not have been able to fulfil his good deeds. However, Madritsch has not always been a hero with a mission to save lives. Just like Schindler, Madritsch came to Kraków to earn easy money in a country that suffered under the Nazi-occupation. Even though he presented himself after the war as a pacifist, as a producer of uniforms for the Wehrmacht, he was part of the German war industry. However, he did what many of his colleagues did not do: taking care of his employees and protecting them from prosecution. Jewish employees may have been cheap, but for Madritsch they were not interchangeable. Together with his manager Titsch, he stood up for them and made a working climate as safe as possible, whereas other entrepreneurs or enterprises like the German chemical concern IG Farben exploited Jewish prisoners. There was no "destruction through labour", as in Auschwitch-Monowitz, a labour camp of IG Farben.

It is certain that many Jews managed to survive, thanks to their work in one of the Madritsch factories. Apart from the 53 that were sent to Schindler’s factory in Brünnlitz, Margit Raab and William Kornbluth also managed, thanks to their work for Madritsch, to escape deportation to an extermination camp and then managed to find their way elsewhere independently (and a lot of luck). An unknown number of Jews could, with the help of Madritsch go into hiding with Polish families or escape to Slovakia and Hungary. Madritsch, who died on June 11, 1984, and was buried at the Vienna General Cemetary, could never have done his rescue work successfully without the support of, in particular, Bosko and Titsch. He might have been more successful if he had been able to transfer more of his employees after the closure of Camp Plaszów to his factory in Lower Austria or if he had managed to get more of his employees on "Schindler’s list". However, pushed by the bureaucracy and the cold calculation of the SS, he eventually gave up his struggle, whereas Schindler pulled through. The latter condemns Madritsch to forever remain in the shadow of Schindler, although both men were cut from the same cloth in the sense of righteousness and humanity.

Notes

- Madritsch, J., Menschen in Not, p. 9.

- Raab-Kalina, M., in: Stolen Youth, p.214.

- Ibid., p.215.

- Crowe, D.M., Oskar Schindler, p. 404.

- Madritsch, J., Menschen in Not, p. 26.

- Kornbluth, W., Sentenced to Remember, 102-103.

- Ibid., p. 108.

- Ibid.

- Crowe, D.M., Oskar Schindler, p. 178.

- Ibid., p. 408.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- denazification

- Post war policy of the allies in Germany to punish Nazi war criminals and to remove known Nazis from positions of power or public service.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem is Israel’s national Holocaust memorial where in addition to Jewish victims and resistance heroes, also non-Jewish helpers of Jews during the World War 2 are being honoured. Those non-Jewish are called the Righteous Among The Nations. Until the mid 90’s trees were planted for these rescuers. In 1996 a special remembrance garden was established displaying all of the names of the helpers. Every year new names are added.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- CROWE, D.M., Oskar Schindler, Verbum, Laren, 2006.

- FRAENKEL, D. & BORUT, J., Lexikon der Gerechten unter den Völkern, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen, 2005.

- GILBERT, M., The Righteous, Transworld Publishers Ltd, Londen, 2002.

- KENEALLY, K., Schindlers Lijst, Luitingh Sijthoff B.V., Amsterdam, 2002.

- KORNBLUTH, W., Sentenced To Remember, Associated University Presses, Cranbury, New Jersey, 1994.

- MADRITSCH, J., Menschen in Not, Eigen beheer, Wenen, 1946.

- O'NEIL, R., Oskar Schindler, Susaneking.com, League City, Texas, 2010.

- PRENGER, K., In de schaduw van Schindler, Just Publishers, 2022.

- RAAB KALINA, M. e.a., Stolen Youth, Yad Vashem, Jeruzalem, 2005.

- SPECTOR, S. & ROZETT, R., Encyclopedie van de Holocaust, Kok, Kampen, 2004.

- Archive Institut für Zeitgeschichte Wenen.

- Stadt- und Landesarchiv Wenen.

- Stolze, Jackie Hartling, 'Defying Darkness', 15 september 2008, op: Frinnell.edu

- USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Yad Vashem

- Thanks to Anne Palmer for her help in correcting the text.