Introduction

Starting at dawn on June 10, 1942, shots rang out over the emptied village of Lidice, Czechoslovakia as groups of ten inhabitants were taken from a farm building cellar into an orchard and executed by Nazi firing squad. The process continued all day with short breaks for the executioners to buck up their courage with schnapps. The entire male population of the village was eliminated. Innocent Lidice was paying the butcher’s bill for the assassination of the Third Reich’s third most powerful man – SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich.

Czech Underground

The Versailles Treaty created the state of Czechoslovakia from fragments of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the First World War. Hitler precipitated a European crisis in 1938 with demands for protection of German nationals living in an area of Czechoslovakia known as the Sudetenland. As part of the Munich Pact of September 1938, the Sudeten territories were annexed into Germany. After Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia were proclaimed a protectorate and part of the Greater German Reich. The remaining Czech province of Slovakia became a German client-state known as the Slovak Republic. Czechoslovakia ceased to exist.

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia came under the administration of Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath, a Prussian aristocrat more interested in hosting hunting and dinner parties with German industrialists and military officers and their Czech collaborators. A dummy government pliant to Germany’s wishes was installed under President Dr. Emil Hácha. The protectorate was important to the Third Reich as a source of coal and as a major arms manufacturer.

A small cadre of Czech émigrés in London was led by the former Czech President Dr. Edvard Beneš, who formed the Czechoslovakian National Committee to unite emigrant groups in October 1939. One month after the fall of France, Beneš’s organization was recognized by the British Foreign Office as a government-in-exile. Chief of the Czech intelligence service was Lieutenant Colonel František Moravec, who had operated networks of spies in Germany including some placed within the Abwehr or German Military Intelligence before the war. Moravec had left his country on March 14, 1939 just before Nazi tanks rolled across the border.

Dr Edouard Benes, the exiled President of Czechoslovakia, with Czechoslovak Air Force personnel and troops. Source: Imperial War Museums

Active Czech resistance formed under Úvod (Central Committee for the Homeland Resistance), which co-ordinated two groups, the National Defense, comprised mainly of professional soldiers and reserve officers, and the OSVO, a resistance organization sheltered within a pre-war Czech gymnastics group known as Sokol. The Communist underground operated independently. Resistance started soon after the outbreak of war and mainly took the form of demonstrations honoring Czech history and clandestine anti-Nazi newspapers. During the winter of 1939/40, the National Defense and Benes’s intelligence gathering forces were smashed. Furthermore, in September 1940, 3,000 leading citizens were arrested by the Gestapo. Further protests were met with harsh reprisals. The universities were closed, students and intellectuals were sent to concentration camps, and martial law was declared. In the fall of 1941, a left-wing trade union group was betrayed and liquidated. In September 1941, the Soviets, in cooperation with London, dropped four Czech soldiers near Brno. Three were almost immediately captured and the fourth betrayed 160 Czech resistance supporters, who were sent to concentration camps. Czech resistance was in shambles.

To rebuild the resistance organization, Beneš encouraged a plan in which British-trained Czech parachutists and equipment were airdropped into the occupied territories for targeted sabotage and assassinations. The results were less than spectacular. The first agent, Otmar Riedl, who carried codes and radio crystals for the Home Army, missed his objective by hundreds of miles and landed in the Tyrolean Alps. He was quickly captured but only charged with illegal border crossing having previously dumped his secret cargo. A pattern developed that was to become all too common. During the next thirteen months, twenty-seven parachutists were delivered to Czechoslovakia with little results. Radio transmitters were lost or damaged, men were misdropped, and others were exposed by locals who feared German reprisal.

In Operation PERCENTAGE, Lance-Corporal František Pavelka was sent to re-establish communications with the decimated resistance workers. Dropped far to the west, he missed his contacts but made his way to Prague. Three weeks later on October 25, 1941, Pavelka was betrayed and arrested. Significantly, he carried on him addresses of two safe houses in the small Czech village of Lidice. Pavelka was eventually tried in Berlin and executed in Plötzensee Prison in January 1943.

However, Czech efforts were not completely without success. In June 1940, Captain Václav Morávek of the National Defense re-established contact with Paul Thümmel, a German counter-intelligence officer who was part of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris’ Abwehr and stationed in Dresden. Since 1937 Thümmel worked as a double agent for the Czech Secret Service under the code name A-54. Thümmel supplied the Czechs with German Army movements across Europe including plans for the invasion of Czechoslovakia, the attack upon Poland, the attack on France, and the invasion of the Soviet Union. This final intelligence was reported to London two and one-half months before it occurred. The information was forwarded to Stalin, who ignored it.

Thümmel maintained wireless contact with London through Morávek. In October 1941, Morávek’s radio transmitter was discovered and, although Morávek escaped, his operator was captured and confessed that Morávek had a well-placed operative in Wehrmacht headquarters. The Gestapo found information that was known to only three people including Thümmel and the other two were thought to be above suspicion. On October 13, Thümmel was arrested. However, as a highly decorated member of the Nazi Party who had friends in high places including Himmler, Thümmel was released after six weeks of questioning. In March 1942, Thümmel was again arrested on new evidence of a 1939 meeting with British Secret Service in The Hague. He was to remain in prison until his execution in Theresienstadt Camp in April 1945.

Despite the setbacks, the Czech resistance movement continued to expand. SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Hermann Frank, von Neurath’s deputy as State Secretary for the Protectorate and Hitler’s representative in the provinces, instigated unrest to overcome Hitler’s reluctance to replace Neurath. His actions convinced Berlin that a stronger hand was necessary. Von Neurath was summoned to Berlin to answer for his failures and became ill. He was replaced by Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi Party’s clean-up man. If there was a dirty trick, instigation, or even mass murder to be planned, Heydrich was the man for the job. Overtly or covertly Heydrich masterminded many of the Third Reich’s atrocities. He organized Krystallnacht, the attack upon Jews and Jewish-owned properties across Germany during the night of November 9/10, 1938; as commander of the Sicherheitsdienst (Nazi Party Security Service or SD), he sent saboteurs into Slovakia to ferment tensions between Slovaks and the Czech government; he staged frontier incidents with SD men in Polish uniforms attacking border guards as justification for the Nazi invasion of Poland; he commanded SS-Einsatzkommando units on the Eastern Front, whose mission was to execute those thought undesirable by the Nazis; and most notoriously, he chaired the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942 that formulated the Final Solution of the Jewish Question, that is, the transportation of Europe’s Jewish population to extermination camps. Reinhard Heydrich was considered by his contemporaries to be more intelligent and less scrupled than his superior the notorious Heinrich Himmler, making Heydrich a very dangerous man. Heydrich may even have seen himself as the ultimate successor to Adolf Hitler. Part of his plan for further advancement was to remove himself from the shadow of Himmler and prove his ability to administer conquered lands.

On September 27, 1941 Reinhard Heydrich became Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia and in that capacity he no longer reported to Himmler but directly to Hitler. He was at the pinnacle of power as he also retained his position as head of Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), the state security organization under Himmler which controlled the Secret State Police or Gestapo and the Sicherheitsdienst. Heydrich was determined to eliminate Czech unrest and his arrival in Prague led to mass arrests, trials, and deportations. Within two weeks, the new regime had arrested 5,000 people including Czech Prime Minister Alois Eliás who, despite his position within the occupation government, had maintained relations with the underground National Defense.

Heydrich's rule in Czechoslovakia was not hated by everyone. He employed a carrot and stick approach in which his first actions were repressive. However, after he demonstrated his power to the Czech population, his rule was accepted in certain circles, especially among the workers employed in the Czech armaments industry to whom he offered increased rations, time-off, and other benefits. Czech exiles in London noted Heydrich’s pacification of the population with alarm and saw his assassination not only as his elimination but also as a driver of an increase in Czech resistance that the expected brutal German reprisals would provoke.

Operation Anthopoid

In December 1941, a Halifax bomber left Tangmere Air Base in southern England to deliver ANTHROPOID and two other parachute teams to Czechoslovakia; Silver A, whose three-man team was to re-establish radio communications with A-54, and Silver B, whose two men carried a radio transmitter for the resistance movement. Compartmentalization kept knowledge of ANTHROPOID’s mission from the other parachute teams. At 2:24 am on December 29th, ANTHROPOID was dropped first followed shortly afterward by Silver A and Silver B. The targeted drop zones were hidden by a fresh snowfall that had obliterated all geographic markers. Everything – towns, roads, rivers, and field boundaries – were covered by a white blanket. Thus, all three teams started their adventures completed off target and lost. ANTHOPOID’S resistance contacts were over 100 hundred miles away. Gabčík and Kubiš were on their own. Although the members of Silver A split up upon landing, its leader, Alfred Bartoš did manage to re-establish contact with Morávek. Silver B’s radio transmitter was damaged upon landing and its mission was a complete failure.

Worse still, upon landing, Gabčík injured his foot. The two-man team buried their parachutes in the snow and struck out for safe shelter which they found in the tunnels of an abandoned quarry. Fortunately, the forester who found Kubiš and Gabčík in the quarry was a member of Sokol, which was able to provide forged papers and travel documents. Transported to Prague, the pair found shelter in a tenement apartment.

Silent for eight weeks after their drops into Czechoslovakia, the Czech Home Army in London began to assume, in the face of new and intense security measures and a similar silence from the Silver B team, that they had all been captured or killed. The parachute plan appeared an utter failure. Then on March 1, 1942 London was informed that ANTHOPOID was safe. In early April, the team, feeling the need for additional resources, recruited Warrant Officer Josef Valčik, a member of Silver A, to join the team. While the Morávek family apartment became headquarters and sanctuary for many of the paratroopers, the ANTHROPOID team sheltered at the apartment of the Novák family in the Libeň district of Prague.

On March 21, 1942 Morávek went to a Prague park that happened to be under observation by the Gestapo. Suspicious of his behavior, the Gestapo agents attempted to arrest Morávek for questioning. Morávek was not going to be taken and entered into a running gun battle with the agents. Seriously wounded, Morávek committed suicide. Unfortunately for the future, he carried coded signals and a photograph of Valčik for the preparation of new false documents. The Gestapo was able to trace Valčik to the village of Pardubice but there lost the trail.

On March 26, 1942, parachute groups OUT DISTANCE and ZINC left England. ZINC was to form the nucleus of a new resistance organization and OUT DISTANCE was to sabotage the Prague gas works. The pilot could not find his objective in the thick spring fog. The drop was disastrous for both teams. OUT DISTANCE’s commander, Lieutenant Adolf Opálka injured his leg and Corporal Ivan Kolařik lost his forged identity card. They separated to find their own ways to Prague. The third member of the team, Warrant Officer Karel Čurda, hid on his family farm 90 miles south of the city.

The ZINC team missed Bohemia and Moravia entirely and, at first light, found themselves in Slovakia. On the run and pursued by the gendarmerie, they made for the border. Sergeant Vilém Gerik, the junior member of the ZINC team was alone and became fearful. He turned himself in to the local Czech police. Transported to Gestapo headquarters in Petschek Palace, Prague, Gerik told all – names, targets, locations – everything.

The assassination

Despite the long delay, Kubiš and Gabčík continued their mission – Heydrich’s assassination. They explored the terrain around Heydrich’s confiscated Schloss Jungfern-Brescau in the rural village of Panenské Břežany 16 miles north of Prague. They noted every detail and planned several possible assassination attempts before settling upon a course of action. Repeated observation of Heydrich’s route to his office in Czernin Palace within the Hradcany district had shown him to pass a point where his vehicle had to slow to maneuver a sharp turn in the road on a hill leading down to the Traja Bridge over the Vltava River in the Prague suburb of Holešovice. Kubiš and Gabčík selected the site for an ambush.

A Czech watchmaker entered the reichsprotektor’s office to repair an antique grandfather clock. As he prepared to start his work, he saw a slip of paper of the reichsprotektor’s desk noting the itinerary of May 27 when Heydrich was to leave Prague for a meeting with Hitler to discuss the occupation strategy in northern France and Belgium. Heydrich expected to receive an increase his control over the German occupied territories and may not return to Prague for some time. The watchmaker passed the information to a housemaid who passed it to the Czech Resistance. The three assassins had to act.

Shortly before 9:30 am on May 27th, Gabčík, the man selected to carry out the killing, hid a Mark II FF Sten submachine gun under a raincoat which he carried draped over his arm despite the warm May sunshine. Kubiš carried a leather brief case holding two British-made modified antitank grenades that were to be the backup plan should Gabčík fail to strike his target. Valčik, armed with only a shaving mirror to warn of the target’s approach, took his position 100 meters up the hill across the road from Villa Stockar where he had a clear view of Rudé armády to a curve 180 meters farther north.

Gabčík and Kubiš adopted a false casualness, looking as if to cross the busy roadway without actually doing so. Heydrich was late. As the minutes ticked by, they crossed and recrossed the road, carefully avoiding the trams that were screeching as they negotiated the sharp curve. A policeman appeared and the two men split in different directions with Kubiš going uphill. The commuter crowd thinned, exposing them even further to curious observation. By 10:00 am Gabčík and Kubiš were concerned that Heydrich was not going to his office that day. Perhaps he was not even in Prague; perhaps he had already flown to Berlin. Not until 10:25 am did Valčik flash the warning signal that their quarry was approaching.

Both men positioned themselves on the inner side of the hairpin curve. A few minutes dragged by before the dark green Mercedes 320 Cabriolet down shifted as it neared the bend. Heydrich, in his black SS uniform, sat beside his driver, SS-Oberscharführer Johannes Klein. Gabčík dropped the raincoat and lifted the barrel of the Sten as he pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. He attempted again to fire and again nothing. By now, Heydrich had seen his attacker and, against all logic, ordered Klein to stop the vehicle. Heydrich drew his revolver to execute the assassin personally.

Klein brought the vehicle to a sudden, skidding stop just as a tram slowly ground its way up the hill. Kubiš threw the modified grenade which exploded upon impact against the running board just in front of the right rear fender and behind a lurching Heydrich who was struggling to open the car door. Heydrich fired a couple wild shots into the smoke and dust raised by the explosion before staggering to the ground holding his side. Passengers left the tram to view the source of the noise.

Reinhard Heydrich's Mercedes after the assassination attempt. Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1972-039-44

Klein pursued Gabčík around a sharp corner to Brauner’s butcher shop. Gabčík sought Brauner’s protection in a corner of the shop, but Klein caught up with him. A brief exchange of shots left Klein wounded in the ankle and thigh. Gabčík escaped. Kubiš, for his part, was too near Heydrich’s car and received a back blast of splinters. With his face bleeding profusely, he staggered onto his bicycle, pedaled down the hill and across the bridge, and directly to a resistance safe house. Later that afternoon, Kubiš moved to the home of a railway worker also named Moravec, where a supportive doctor treated his wounds before he spent the night in the apartment. Valčik mingled innocently with the crowd and just wandered away.

Meanwhile, at the hairpin turn, a passing bakery van refused to take the bleeding man in the black SS uniform. Instead, Heydrich was loaded into the rear of a delivery van among cartons of floor wax. Unknown to the witnesses, Heydrich had been mortally injured. The bomb, which had missed entering the open car, was powerful enough to blast fragments into Heydrich’s back and internal organs. Rushed to the Bulovka Hospital only one kilometer away, x-rays showed one smashed rib, a punctured diaphragm and bomb fragments in his spleen. The head of the Prague German Clinic, Professor Dr. Hohlbaum, performed surgery that also found minute particles of leather and horse-hair upholstery in the spleen. Reinhard Heydrich would take seven painful days to die.

Heydrich's funeral was one of massed Nazi pageantry. On June 5th, an SS detachment led by torchbearers escorted a gun carriage carrying the reichsprotektor’s coffin through streets cleared of civilians but lined with thousands of SS-men to the courtyard of Hradcany Palace for display. Flanked by flaming torches and beneath a gigantic, wooden Iron Cross, Heydrich lay in state for two days. On June 7th, a special train bore the coffin to Berlin and the ritual continued as the body lay in state in the SS Reich Main Security Office on Prinz-Albrecht Strasse for two days. The funeral service was attended by the Nazi glitterati in the enormous Mosiac Room of the New Reich Chancellery to the somber tones of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. Orations were given by Himmler and Hitler before the coffin left the room to the tones of the funeral dirge from Beethoven’s Eroica. Hitler bestowed the German Order, the most important award of the Nazi Party that was only given to eleven other individuals.

Important guests at Heydrich's funeral. From left to right on the front row: Reinhard Heydrich funeral. Emil Hacha, Otto Meissner, Karl Hermann Frank. Source: Public domain

A military-led procession brought the gun carriage to the Invalidenfriefhof military cemetery in Berlin and Heydrich was buried among the Pantheon of German military greats – Richthofen, Udet, and Todt. In Prague, a monument bearing a bust of Heydrich was erected near the hairpin turn on Holešovice and guarded day and night by two SS-men.

Manhunt and reprisals

Under orders from Himmler and while Heydrich lay dying in his hospital bed, Karl Frank assumed temporary command. Roadblocks sealed every exit from the city and SS reinforcements rushed to Prague. A reward of one million reichsmarks was authorized by Hitler in a personal telephone call to Frank. By 4:30 pm on May 27th, a state of emergency, martial law, and a curfew were declared over Prague radio. Hitler and Heydrich’s successor SS-Obergruppenführer Kurt Daluege believed the assassination marked the beginning of a general Czech uprising. Frank correctly believed that it was an attack from outside forces – perhaps British or Soviet. Frank worked to temper Hitler’s thirst for revenge on the Czech people that he felt would only worsen matters.

A Czech newspaper reports on the assassination of Heydrich and the declaration of martial law. Source: Public domain

Before the day was over, thousands of Czech hostages were captured and one hundred were randomly selected by Frank and shot at nightfall. One of the first to be executed was the already condemned Alois Eliás. In Berlin, 152 men and women who had previously been identified as Jewish were taken into custody and shot. Three thousand Jews were transferred from the Theresienstadt old-age ghetto to Dachau. The largest police manhunt in European history was launched to find the attackers and their accomplices. It uncovered nothing.

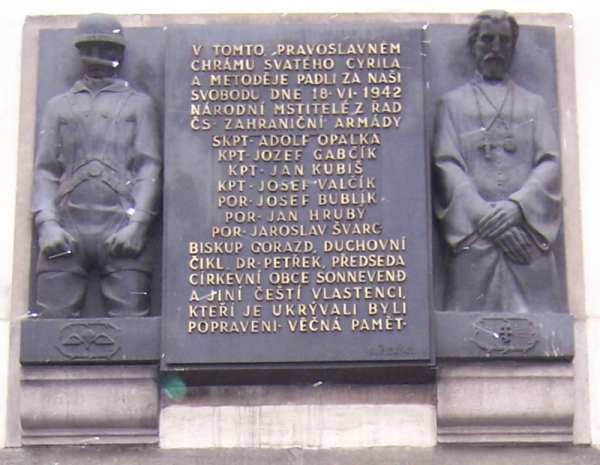

The assassins’ implemented the first stage of their escape plan. They sought shelter in the crypt of the Ss Cyril and Methodius cathedral, formerly the Saint Karel Boromejsky church, on Resslova Street. Although, forged identity papers and workman’s clothing had been prepared in anticipation of leaving Prague after the first flush of search died down, they would get no farther than the crypt.

The Gestapo’s only hard evidence were the Sten gun, bicycle, briefcase, and raincoat left behind during the mad scramble to escape the assassination site. The articles were displayed in the window of Bata shoe store in Wenceslas Square in central Prague. Rewards were offered for information regarding the owners of the items. On May 28, the Gestapo, now under increasing pressure to show progress in its manhunt, guessed that Valčik, who they had almost caught in Pardubice in May, was somehow connected to the assassination. It was a thin lead, but little else remained. A notice displaying Valčik’s photo and offering a substantial reward appeared on all public news boards in Prague.

Lidice

On June 3rd, Jaroslav Pála read a letter addressed to an employee who happened to be on sick leave, Ann Maruščáková, a worker in his battery factory in Slaný. The text vaguely referred to the writer accomplishing what he had set out to do, his anxiety, and one final attempt to see the young woman. The equivocal style of the wording raised the Pála’s suspicions. He reported his find to the Czech Gendarmerie (rural police) and a gendarme was dispatched to investigate. The gendarme was not impressed by the sketchy story, but Pála’s insistence convinced superiors to telephone the Gestapo offices at Kladno and the gendarme delivered the seemingly innocent love letter to the Gestapo’s Thomas Thomsen, deputy chief of the Kladno station.

Ann lived in Holousy, a collection of farm buildings roughly 6 miles north of Lidice. Her home was searched and, although nothing incriminating was found, she was arrested. Thomsen’s superior, SS-Hauptsturmführer Harald Wiesmann, now took over and under his questioning, Ann admitted to a liaison with a young man she had met. In an innocent act that would have terrible consequences, Ann admitted to her young lover that she had friends in Lidice. The young man had asked her to convey greetings to one Josef Horák. Furthermore, Ann knew that Josef Horák had escaped to Britain in 1939. She even suggested that he might have been a parachutist. In fact, Horák and a neighbor, Josef Stříbrny, had both been in the Czech Air Force and had joined the RAF.

The hunt intensified. Wiesmann traced the young man’s bicycle registration number to the Kladno Iron Works. Local police revealed that several Horák families lived in Lidice, but only one had a son of about the right age. That night, Wiesmann’s unit, augmented by four Gestapo men from the now alerted Prague station, searched Čabárna, a farming hamlet situated between Lidice and Holousy, but found nothing. Nevertheless, thirty men, the entire male population of Čabárna, were taken to Kladno. Lidice was next on the Gestapo’s list. Five hundred special police from the RHSA commanded by the thirty-year-old leader of the SD in Kladno, SS-Obersturmführer Max Rostock, surrounded and closed off the village – no one was permitted to leave.

A house-to-house search was conducted. Every member of the Horák and Stříbrny families were arrested and a total of fifteen men were taken to Kladno for interrogation. Despite ‘forceful’ Gestapo questioning, most of the men were released to return home. The members of the two families under suspicion were held. Using photographs from the Horák’s house, Ann identified Flight Lieutenant Josef Horák. The Gestapo also brought forward three men from the Kladno Iron Works. Ann identified Václav Říha as her young man. The married Říha admitted asking Ann to carry a message to Lt Horák. The source and motivation of this message remains obscure, but it may have been only an excuse to end their affair. Both Říha and Maruščáková were sent to concentration camps and died before the end of the war.

Although Wiesmann suspected that the story of the letter was exaggerated, he forwarded the reports to Prague Gestapo Headquarters. Desperate to demonstrate their efficiency despite two weeks of fruitless searches and thousands of executions of innocents, the Gestapo latched onto the story. Lidice was doomed.

There appears little doubt that the destruction of Lidice was ordered by Karl Hermann Frank. The young girl’s mysterious letter became the justification for selecting Lidice for the reprisal. After the war, Frank blamed the destruction on an order from Hitler. What we do know for sure in that on June 9th SS-Obersturmbannführer Horst Böhme, commander of the Prague Security Police (SD), made a paper record of a telephone message from Frank ordering the elimination of the people of Lidice and the erasure of the village.

At 10:00 pm on June 9th, Böhme and SS-Standartenführer Dr Geschke, chief of the Prague Gestapo, personally led a Gestapo detachment supplemented by units of the Schutzpolizei to Lidice’s main square. Wiesmann read the Fuhrer’s Order to the assembled captors which ended with ‘…die Bevölkerung erschossen.’ (…the population to be shot.) All the houses in Lidice were searched. All males above fourteen years were gathered in the courtyard of the Horák farm, women and children were herded to the local school.

The well-organized Gestapo first secured anything of value – the town’s meager funds, accounts, property records, livestock, agricultural machinery, and food stuffs. As the population was collected, they were relieved of their money, savings books, and jewelry. The communal registry was used to identify each citizen and their age. A total of 173 men were held on Horák’s farm, 11 who were working that night at the iron works, escaped immediate capture.

The empty houses were methodically searched, and items of value loaded upon trucks – sewing machines, furniture, bicycles were all taken for the people of Lidice would have no further use for them. They plundered the village’s St Martin church for its holy vessels.

At 7:00 am, Frank arrived and the destruction began. The women and children were loaded on trucks and transported to Kladno. As the last vehicles left the village, the houses were set afire – one by one until the whole community was one large blaze. Horák’s farm became an execution ground. Mattresses were placed against a wall at one end of the Horák’s cherry orchard facing two machine guns. The first group of ten men was brought in front of the mattresses. There was no trial, no judge, no reading of accusations, no testimony, no evidence, and no reading of sentences. With a nod from Böhme, a squad fired upon the ten victims. The squad’s NCO then shot each body in the head with his pistol. Then the next ten were brought forward and the process repeated.

After fifty had been executed, a pause was taken and schnapps served to the executioners. Three could not go on and were replaced. The executions continued. Ten more were shot – then ten more – then ten more. The 73-year-old parish priest, Father Josef Štemberka, was one of the last. In one last indignity the 173 corpses were searched for gold – wedding bands and gold teeth were removed.

Nine of the iron workers were traced to Kladno where German guards arrested them. They were taken to Prague and executed. Two hid in the forest until hunger forced them to seek the aid of a forester. He betrayed them and they were taken to Prague and executed. Eight men from the Horák and Stříbrny families, still in custody in Kladno while their community was raised, were taken to Prague and executed.

The Lidice women and children were gathered into the Kladno Technical Gymnasium and each was registered. On June 12th, the children were gathered in the Kladno schools’ gymnasium. Individually called forward, the children were separated from their anguished and wailing mothers. At 8:00 pm the women were loaded on canvas topped trucks and driven away. Of the 185 women sent to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, 53 did not survive the war. Seven nursing mothers with children under 12 months were held at Terezin, and then sent to Ravensbrück. Four pregnant women, including Lt Horák’s sister were held in Prague until the child’s birth, and then sent to Ravensbrück. The infants were never heard of again. Two trucks arrived and were loaded with the 104 children. Taken first to a camp in Gneisenau, those found not suitable for germanization were gassed. Only 17 ever returned to Lidice.

On June 11th, while the women and children remained in Kladno unaware of the fate of their husbands and fathers, thirty Jewish prisoners from Theresienstadt Concentration Camp arrived in Lidice armed with shovels and a barrel of lime. A mass grave was dug into the hard clay undersoil of the orchard. They worked all day and through the night illuminated by bonfires and threatened by SS guards to hurry. By noon the following day, the grave was only three meters deep. The prisoners began the gruesome task of stripping the bodies and placing them into the grave. By nightfall, the task was complete and lime was spread atop the stacked bodies. The grave was covered with earth.

While the Jewish prisoners continued to dispose of the dead, explosions began. Lidice was being erased. German Army engineers were called in to blow up each structure. The church tower collapsed into a cloud of dust. The Reich Labor Service completed Hitler’s order. Tons of soil and rubble were removed, small quarries were filled, and the brook which flowed through the center of the village was rerouted. The village cemetery was destroyed, tombs removed, and graves erased. New roads were built, trees planted, and the entire surface covered with arable soil. The work continued well into 1943.

Capture

By June 14th, Karel Čurda, still sheltering at his mother’s house and reading of the horrible reprisals being meted to Lidice and the Czech people in general, could stand no more. In an unsigned letter to the gendarmerie, he begged for a cessation of the executions and identified Gabčík and Kubiš by name. The police, assuming the letter to be revenge for some personal feud, ignored it. Two days later, Čurda, now more agitated, traveled to Prague and surrendered to the Gestapo. During an interrogation that continued all night, Čurda told all he knew and betrayed the Moravec safe house to the Gestapo. To prove his story, he correctly identified items left behind by the assassins.

The Gestapo searched the Moravec apartment. Although they found no evidence of the resistance, Maria Moravec, fearing the worst that the Gestapo could do, asked to use the toilet. There she bit hard on a cyanide capsule and died moments later. The horrified Moravec’s 20-year-old son, Vlastimik known as Ata, revealed the church sanctuary in the crypt of Ss Cyril and Methodius Orthodox church in Prague. Both Ata and his father were executed at Mauthausen on October 24, 1942.

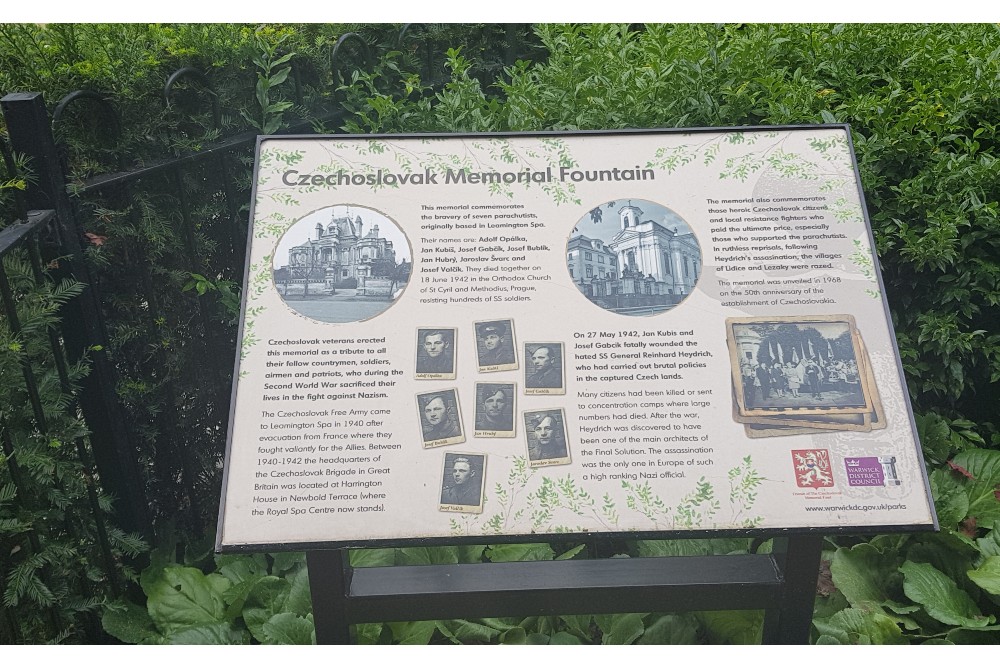

At 2:00 am on June 18th, members of the Gestapo and two battalions of SS men surrounded the church. The area was evacuated, and two machine guns were positioned on rooftops to dominate the church entrance. Inside were the three assassins, Gabčík, Kubiš, and Valčik, along with four other parachutists, Jaroslav Švarc, Josef Bublík, and Jan Hrubý, and their commander Lt Adolf Opálka.

Opálka, Kubiš and Švarc were on guard in the choir gallery, which offered command of the church entrance and provided views of the streets outside. They witnessed the arrival of the SS troops. At 4:15 am, Gestapo men entered the church and were fired upon by Opálka. They withdrew to leaving the fighting to the SS. While machine guns fired through the church windows and pinned down the three men in the choir, SS men stormed into the nave. A gun and grenade battle raged with the SS making gradual progress toward the gallery stairway. After three hours of fierce combat, Opálka was dead from wounds and Kubiš and Švarc, seriously wounded, shot themselves in the head.

The Germans wanted live parachutists. An interpreter spoke with the four men in the crypt through a small air shaft that opened onto the street. The men ignored the interpreter’s pleas for surrender. Čurda was brought forward, but his pleas only brought retaliatory gun fire. The extensive crypt extended beneath the floor of the nave and proved difficult to enter. Tear gas was thrown down the shaft with little effect. The Prague Fire Brigade was called to flood the crypt, but the parachutists used a ladder to reach the narrow-slit opening to cut the hoses and diverted the water toward a sewer that ran to the nearby Vltava River. The use of explosives against the solidly built church was out of the question. Eventually the German forces snagged the ladder and pulled it through the opening. The Czechs now had no way to defend the slit.

Finally, a stone slab which covered the tomb of an ancient Bohemian nobleman and the crypt entrance inside the church was discovered. Firepower was brought against the air shaft and the crypt entrance. The first SS man to attempt forcing the crypt was shot through his legs. But using hand grenades and machine pistol fire, six SS men got down to the crypt floor where they engaged the four survivors in a second fire fight. Then, as with the parachutists in the choir, shots rang out. The four wounded men also committed suicide. Čurda was brought forward to identify the assassins’ bodies.

While the fighting progressed through the church, the Gestapo arrested the church’s bishop, priest, and three members of the congregation. Over 300 members of the Sokol organization, suspected members of the Red Cross, and Orthodox Church members were also arrested. On October 3, 1942 a show trial began for the religious including the bishop. They were found guilty and shot. All relatives of Kubiš and Valčik and members of the resistance network that had been betrayed were arrested and sent to Terezin Concentration Camp. On October 24th, 236 men and women were sent by train to Mauthausen and gassed. Gabčík’s family escaped reprisal as, being Slovakian; the peculiar political position of Slovakia in the German Reich protected its citizens from Gestapo terror.

Monument for the victims of the German attack on the hiding place of the parachutists in the church. Source: Koos Winkelman

In Pardubice, First Lieutenant Alfréd Bartos, commander of Silver A, shot himself while being pursued by Gestapo; Lance-Corporal Jiří Potůček was betrayed and shot by a gendarme. On June 24th, Ležáky, another even smaller hamlet was surrounded and destroyed. Thirty-four men and women were executed. Their homes were leveled. Later twenty-two citizens of Bernartice were executed for sheltering parachutists.

By December 1942, of the twenty-six parachutists dropped into Czechoslovakia, fourteen were dead, three in jail, and two had changed sides. By 1943, despite the delivery of additional commando units, every parachutist in Czechoslovakia was either dead or cooperating with the Germans.

As the war progressed, Dr Hacha’s health deteriorated and his role as a puppet of the Nazis continued. After the liberation of Czechoslovakia, Hacha was arrested and held in Pankrác prison where he died shortly afterward on June 6, 1945. Von Neurath was tried at Nuremberg where he was sentenced to 15 years in Spandau Prison in Berlin. He was released in 1954 for health reasons having suffered a heart attack and died two years later at age 83.

Gerik and Čurda were tried in February 1946, found guilty of treason and executed. Frank was imprisoned as a war criminal by US forces in Germany. Returned to Czechoslovakia by the Americans, Frank’s trial began at 10:00 am on May 22, 1946. By 1:30 that afternoon, he had been found guilty, sentenced to death, and hanged. Harald Wiesmann was tried, convicted, and executed in Prague on April 24, 1947. Max Rostock was arrested after the war and turned over for trial in Prague. Although sentenced to death in 1951, Rostock worked until 1960 for Czech and German authorities exposing former members of the SD and eventually settled in Bremen, Germany. He died in 1986.

Lidice Immortalized

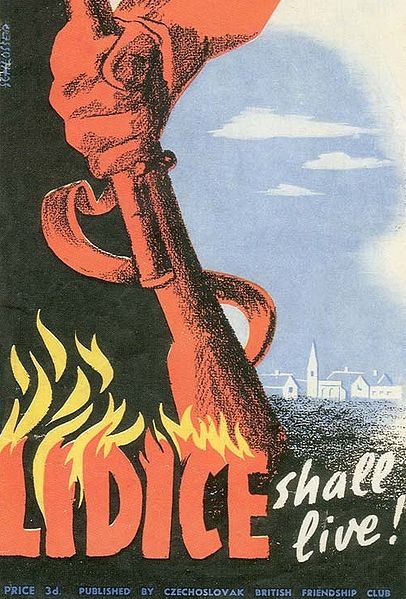

Almost immediately after its destruction, ‘Lidice shall Live" committees were established around the world to collect funds to re-establish a new Lidice on a hillside overlooking the destroyed village. Towns changed their name to Lidice and the destruction of the quiet farm community became a rallying cry against Nazism. Heinrich Mann, then living in California wrote a satirical novel, ‘The Protektor’; Douglas Sierk directed the film ‘Hitler’s Madman’; poems were written by Cecil Day Lewis and Edna St Vincent Millay; Berthold Brecht wrote lyrics for ‘The Song of Lidice’ for the motion picture ‘Hangmen also Die.’ A memorial ceremony for Lidice was held in the bombed-out Coventry Cathedral. US War Bonds were sold under the slogan ‘Remember Pearl Harbor and Lidice.’

The political fallout achieved Beneš goals, but at a terrible cost. Beneš became the undisputed leader of Czech émigrés in the eyes of the Czechs and the Allies. Britain and France finally repudiated the Munich Agreement of September 1938 which had eliminated Czechoslovakia. The pre-agreement borders were now recognized by the Allies. Britain agreed that, after the war, Sudeten Germans would be forcibly removed from Czech territory. After the war, the Ravensbrück survivors were brought back to Lidice, but it was now a Lidice without husbands, children, houses, farms, church, or even cemetery.

The assassination is still remembered in Prague. Among large graffiti-scarred buildings in a Prague suburb between the interchange of several highways, a small park holds the Memorial to ANTHOPOID, a column topped with three figures each with outstretched arms. Directly south is the greatly expanded hospital complex where Heydrich was taken for treatment and where he eventually died. Flowers frequently appear upon a ledge beneath the air shaft opening in the wall of St Cyril and Methodius Cathedral and its crypt has been converted to a memorial museum.

The Nazi extermination program, so meticulously planned by Heydrich, was implemented with Germanic efficiency. Code-named ‘Aktion Reinhard,’ the mass extermination of Jews in the death camps began in earnest. Within 15 months of Heydrich’s death, two million people had been eliminated in places that became famous for their cruelty – Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.

Information

- Article by:

- Robert Mueller

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- BRADLEY, J. F. N, Lidice: sacrificial village, Ballantine Books, 172.

- DEDERICHS, M.R., Heydrich: The Face of Evil, Greenhill, London, 2006.

- MACDONALD, C.A., The Killing of SS Obergruppenfuhrer Reinhard Heydrich, Free Press, New York, 1989.

- WIENER, J.G., The Assassination of Heydrich, Grossman Publishers, New York, 1969.