Introduction

In July 1942, amidst the marshes southeast of Leningrad, a Soviet army was surrounded and forced to surrender. Among the prisoners was the commander of this army, Lieutenant-General Andrei Vlasov, a talented and dedicated officer, considered a favourite of Stalin. During his captivity, he decided to turn against the Soviet state and established – with German support – the ‘Russian Liberation Army’. The story of Vlasov continues to provoke divided reactions – on the one hand, a school that considers him an opportunistic traitor and, on the other, his supporters who consider him a patriotic martyr.

Career in the Red Army

Early years

Andrei Andreyevich Vlasov (in German also spelled Wlassow) was born September 1, 1901, into a poor farmers family in the village of Lomakino, 310 miles east of Moscow. He was the thirteenth and youngest child. At an early age, he left for Nizjni Novgorod, attending a seminary there and subsequently studied agriculture for a short period. However, he did not finish either course. Against the will of his parents, Vlasov decided in the spring of 1920 to join the recently founded Red Army, to fight - in his own words - 'for more farming areas and a better life for labourers'. He followed a short training for officers, after which he was deployed as a platoon commander in Southern Russia and the Caucasus during the civil war which had broken out between the Red and the White armies.

After the civil war, Vlasov remained in the service and made a speedy career. During the period between wars, he commanded various companies and battalions, and in 1930, he became a member of the Communist Party. After numerous training and staff jobs, Vlasov, now promoted to Major, was appointed commander of an infantry regiment. In the autumn of 1938, Vlasov, meanwhile to colonel, was transferred to China to become one of Chiang Kai-shek’s military advisers on behalf of the Soviet Union. It saved Vlasov from Joseph V. Stalin’s purges, which affected numerous high-ranking officers, and it was also a result of trust, which indicated the faith of Moscow had in the talented Vlasov.

In December 1939, Vlasov returned from China and was appointed commander of the 99th Infantry Division in the western part of Ukraine and promoted to brigadier general. The division was extremely disorderly, but Vlasov – characterized by a superior as an ‘intelligent and energetic leader’ – managed to put things in order. Shortly after this, his superior declared that the tactical training of Vlasov's troops was of ‘extremely high level'. The people's commissioner (minister) of Defence, marshall Semyon K. Timoshenko, even proclaimed the 99th division the best-trained division of the Red Army. In the autumn of 1940, Vlasov's division excelled during an extended training exercise, personally observed by marshall Timoshenko. During this time, the army newspaper Red Star regularly published articles about the successes of his division. Vlasov had put himself in the spotlight among the army leadership in Moscow, who, in a short time, awarded him with two high orders, which was a relatively rare action in those days. Again, a promotion followed when Vlasov, now a major general, was appointed commander of the 4th Mechanized Corps, a well-equipped formation on the Ukrainian-Polish border.

The German invasion

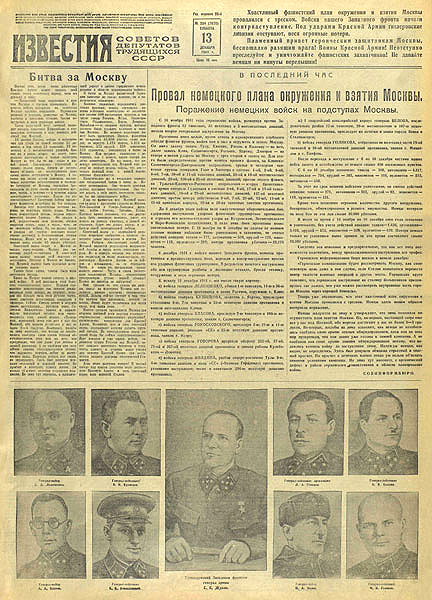

Vlasov’s service record in the first six months after the German invasion proved impeccable. During the first phase of Operation Barbarossa, the Vlasov corps was surrounded repeatedly by units of Heeresgruppe Süd, but Vlasov managed, again and again, to escape to the east. During the summer of 1941, as commander of the 37th Army, Vlasov was responsible for the defence of Kiev, where he held out for a month. Considering the unfavourable circumstances, Vlasov had performed excellently, and soon he became a favourite of Stalin. In November 1941, Vlasov was summoned by Stalin and given command of the 20th army, one of the formations that defended Moscow. The following month, Vlasov's army led one of the most significant counterattacks. He received praise for pushing back the Germans, and his photograph appeared on the front page of the state newspaper Izvestia. Shortly after this, his promotion to lieutenant general followed. Vlasov's good reputation in the Kremlin was also apparent in the memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev, who wrote that Stalin considered appointing Vlasov commander of the Stalingrad front, newly formed in July 1942, an assignment, eventually given to Timoshenko.

The front page of Izvestia of December 13, 1941 where Vlasov (left below and 8 other generals are being praised. Source: Public domain

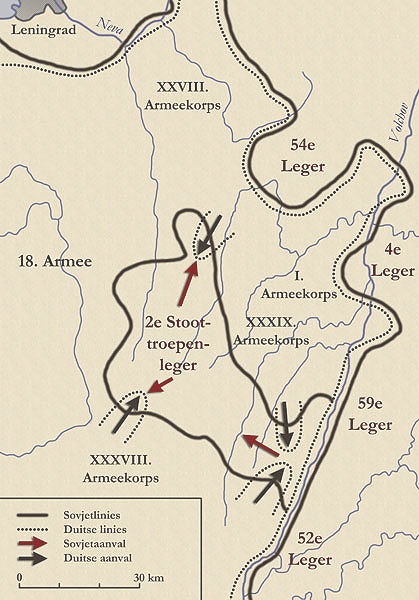

While the Red Army achieved its first successes near Moscow in the winter of 1941-1942, the situation further to the north was very precarious. Numerous armies, such as the Second Shock Army, made arduous efforts to break through the German lines to relieve besieged Leningrad. The Second Shock Army was ordered to keep advancing but proved no match for the fierce German resistance. The army was hampered by a serious shortage of artillery, ammunition and rations, by its need for air support and its poorly trained troops. Moreover, most of the troops – often from the Russian steppe regions – could not cope with the wooded and marshy environment. In an attempt to overcome this situation, the deputy commander, the chief of staff and the chief of operations were all replaced. When the army commander himself became seriously ill, his replacement was sought and was eventually found in General Vlasov.

When Vlasov took over command in March 1942, his army was in a dire situation. It occupied an extended, narrow salient in German territory and only large-scale reinforcements or withdrawing on the initial frontline on the Volchov River could avoid an encirclement. Reinforcements were out of the question. German attacks on the neck of the salient were increasing in intensity and it was not until May 20 that Stalin ordered the Second Shock Army to withdraw. Some divisions managed to escape through a narrow corridor, but on May 20, the army was definitively isolated. In June, Stalin ordered some counterattacks to restore contact with Vlasov’s army, but without success. On June 24, Vlasov ordered his men to make breakout attempts in small groups, but unfortunately, 32.000 troops failed to do so and were taken prisoner. In the east of the salient alone, at least 14.000 troops were killed during the bloody battles. Vlasov himself had lost most of his staff officers during a sudden artillery barrage on his headquarters.

Definitielijst

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kremlin

- Soviet administrative centre in Moscow.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

German POW

Vlasov did not find a way to escape imprisonment and wandered through the woods of the River Volchov for a long time. It was not until July 12 that he surrendered to the Germans. He presumably had spent the previous two and a half weeks considering his options. Since the beginning of the German invasion, Vlasov had been at the front, almost continually, with all the inherent pressure, but this brief interlude before his surrender offered a possibility for reflection. His career in the Red Army was definitively over. As a commander of a beaten army, he would be blamed for the defeat and possibly executed. But, decisive for Vlasov was his growing resentment to the Soviet regime. In March, while trying to protect his army from encirclement, Vlasov had received a letter from his wife containing the news of the arrival of "guests". The secret police had searched their house, despite Vlasov’s high honours and impeccable track record. And then, of course there was the tragic fate of his army, which, in Vlasov’s opinion, had been abandoned by Stalin. Later on, Vlasov wrote that his men’s deaths were senseless, and, consequently, that the Bolsheviks did not represent the interests of the Russian population. "Down there, in the marshes", Vlasov explained, later on, "I finally concluded that it is my duty to call on the Russian people to overthrow the Bolshevik regime and to fight for peace and end this bloody and unnecessary war". He thought he might be able to succeed in this with the support of Germany.

Vlasov did not actively look for Germans but offered no resistance when found by a German intelligence officer. He was taken to the commander of the German 18th Army, Generaloberst Georg Lindemann, his former opponent, who received him cordially. For some time, the two generals discussed the events of the past months, after which Vlasov was taken to a camp for "prominent" POWs. Here, Vlasov met a like-minded person, with whom he wrote a letter to the German authorities, in which he proposed to exploit the anti-Stalinist sentiments among the Russian population and the POWs and to set up a Russian people’s army.

Ideals and ideology

Vlasov’s proposal seems naive, considering the ideological basis of the German invasion. Adolf Hitler had already explained in Mein Kampf that, according to him, the "Judeo-Bolshevik" rulers were bent on world domination. Moreover, according to Nazi ideology, the Slavs were an inferior race. The Ostpolitik, the Nazi German policy concerning the Soviet Union, also dictated that the Russians should be treated as a labour force to benefit German interests. Not all of the Nazi leaders agreed with this ruthless policy. Joseph Goebbels, for instance, the German minister of propaganda, noted in his diary that the Ukrainians initially welcomed the Germans as liberators, but the ruthless way, they were treated made them change their attitude. Goebbels wrote that it might be sensible to install puppet governments in the occupied territories, to regain the trust of the local population. Later on, he even concluded that it would be wiser to wage war against Bolshevism than against the Russian people.

In response to his letter, Vlasov was visited by some pragmatic German officers, who realized that the brutal German behaviour in the east had caused a significant increase of resistant activities among the Russian population. In particular, in the propaganda department of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Intelligence-department Fremde Heere Ost, numerous persons were employed who wanted to review the rigid Ostpolitik. One of them, one Oberleutnant Eugen Dürksen, a propaganda officer attached to the OKW, had been looking for some time for an anti-Stalinist Soviet general who was willing to sign pamphlets that tried to persuade Soviet soldiers to desert. He visited Vlasov in the summer of 1942 and discussed his attitude towards Stalin. The most important opponent of the Ostpolitik was undoubtedly Hauptmann Wilfried Strik-Strikfeldt, a Russian born- and-bred employee of Fremde Heere Ost, who soon became friends with Vlasov. Strik-Strikfeldt was one of the few opponents of the Ostpolitik, which not only served German interests, but was also concerned about the fate of Russia. He convinced Vlasov to take charge of an anti-Stalinist liberation movement.

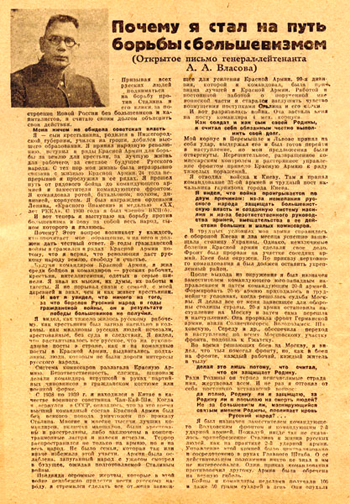

Page 1 of a widely circulated open letter from Vlasov: Why I went into battle with Bolshevism. Source: Public domain

Popularity of Vlasov's movement

Although Wilhelm Keitel, head of the OKW, did not react to Vladovs requests to form a liberation army, Vlasov nevertheless decided to continue his opposition. In the summer of 1942, pamphlets, with Vlasov's signature, were dropped over de frontline to incite Soviet soldiers to desert. These actions were successful. Large numbers of Soviet soldiers deserted because of their sympathy for Vlasov's movement. In addition, a Russian training camp was set up in Dabendorf in November 1942, 19 miles south of Berlin. The men who were trained here were selected by Vlasov's staff, mainly among the Osttruppen, volunteers from the eastern occupied territories, who were in German military service. In Dabendorf, they were taught the ideals of the liberation movement and the flaws of the Stalinist system. Then they would return to their units to spread the viewpoints of the liberation movement. Apart from that, a 40-men editorial staff published two newspapers, Zarya (Dawn) and Dobrovolets (the Volunteer), which also spread the movement's ideas.

At the height of the German advance, almost 70 million Soviet citizens lived in the German-occupied territory. To draw upon this huge source of potential support, in early 1943 Vlasov made several visits to these territories, where he spoke with the population about his ideals. All the hardships the Russian population had endured during the past 12 years were caused by failing government policy. The Kolchoz-system had ruined the country, millions of people were persecuted and the elite of the army had been killed. The incompetent Stalinist clique had lured the country into a pointless war in which millions of soldiers’ lives had been needlessly sacrificed. Vlasov proposed to overthrow the Stalin regime and formation of a new, free Russian nation, with the right to private property and freedom of opinion, press, religion and association.

Vlasov’s speeches invariably drew a large audience and proved a resounding success. Standing 6 feet tall and with his powerful voice, he was an impressive figure. He was no gifted speaker but he spoke with passion, firmness and frankness. His listeners appreciated his his clear and simple language. Vlasov kept hoping that the popularity of his ideas would cause a change of course in Berlin but to no avail. ‘One can only be astonished about the lack of political instinct of our central government in Berlin,‘ Goebbels wrote in 1943. ‘If we would follow, or had followed a better policy in the East, we would certain;ly have made more progress.’ Ironically, Stalin also noticed the effect of Vlasov’s speeches; in Stalin’s words, ‘the general posed at least a large obstacle on the road to defeating the German Fascists.

Vlasov lacked political tact and during a speech in April 1943, he made a clumsy remark. The anti-Stalinist Russians were now the guests of the Germans, he stated, but once they had taken power, the Germans would be their guests of honour. This remark ended up on the desk of SS-leader Heinrich Himmler and he was not amused: it was too impertinent for words that "Untermenschen" dared to invite Germans for something. It seemed the end of Vlasov's liberation movement. Vlasov was no longer allowed to travel through occupied territories and would only be deployed for propaganda purposes. "We will never raise a Russian army", Hitler said to Keitel in June 1943, "that is a delusion of the highest order".

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Mein Kampf

- “My Struggle”. Book written by Adolf Hitler, outlining the principles of National Socialism.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The Russian Liberation Army

Then a period of forced inactivity followed. Vlasov pessimistically considered the future of his movement and struggled sometimes with bouts of depression. He, practical-minded as he was, could not comprehend the unwillingness of the German supreme command. He kept believing that the Nazis based their ideology on logical considerations and anti-Stalinist sentiment and would, some day, act accordingly. Moreover, he was familiar with the Soviet system, in which it was unthinkable that official policy would be criticized without consent from the top. If German officers were allowed to criticize the Ostpolitik, it obviously would imply that the nazi-leadership was ready for a change of course. Strik-Strikfeldt also had limited insight into nazi ideology. He, in turn, was convinced that Hitler would be open for reason if the true situation would be explained to him. "The Führer is always surrounded by people who are blind," he once said. The fact that Hitler himself had devised the Ostpolitik and did not care about other opinions did not occur to Strik-Strikfeldt.

In spite of the slow progress, Vlasov continued to lead his movement. He travelled a lot and spoke with various Nazi leaders, such as Baldur von Schirach and Robert Ley. During the summer of 1944, hope came from an unexpected direction, when Himmler decided to meet Vlasov. The exact reason for this rapprochement from the side of the SS is not clear. Possibly Himmler thought to contact a new source of SS-recruits. Racial considerations were no longer an issue during this part of the war and the SS already had the Kaminsky-Brigade under its command, consisting of Russian troops. According to others, an internal power struggle between Alfred Rosenberg’s Ostministerium and the SS was the reason for the contact, and Himmler wanted to prevent Rosenberg from taking on the Vlasov operation.

Whatever the reason, after a series of postponements, the meeting between Vlasov and Himmler took place on September 16, 1944. Vlasov had regained some of his previous energy and Himmler was impressed by his strong personality and determination. The SS leader authorized the establishment of the ‘Committee for the Liberation of the Russian Peoples’ (Komitet Osvobozhdeniya Narodov Rossii, KONR), the publication of a manifesto and the formation of some Russian divisions. Vlasov would be the chairman as well as the supreme commander of the KONR forces. "Vlasov was moved and proud," Strik-Strikfeldt later wrote. "He had won his battle after all the difficulties and humiliations of the past two years." Himmler indicated that the Germans would recognize the KONR as the true representative of the Russian people and would consider the organization an ally. This last term was of great value to the Russians, it showed that their army was on an equal footing with the Wehrmacht. They were allies, no mercenaries.

The manifesto was published on November 14, 1944, in the castle in Prague - the largest Slavic city, still in German hands. As a representative of the German government, SS-Obergruppenführer Werner Lorenz was present, who indicated once again that the Third Reich would regard the KONR as an ally and would support the organization in its efforts.

Nonetheless, it was clear that the liberation army was established too late. All the occupied territories in the east had meanwhile been recaptured by the Red Army and the Russian civilians who had received Vlasov so cordially could no longer be of use. Still, there was no shortage of recruits, After the Prague ceremony, the news that an independent Russian division was being established spread through Germany like wildfire. Daily, Vlasov's staff received 2,500 to 3,000 requests from Russian labourers and POWs to join the KONR ranks, popularly known as the Russian Liberation Army (Russkaya Osvoboditel'Naya Armiya, ROA).

At the end of 1944, the German press paid much attention to Vlasov, "the new wonder weapon". He would – as was proclaimed – drastically influence the course of the war. However, Vlasov was well aware of the military reality. He understood that his army was not going to play a key role aat the front any longer. But Vlasov looked ahead: "If Germany could hold out for another 15 months", he told Strik-Strikfeldt, "then we would be given time to build up a significant force of power." This force would, with the support of the Wehrmacht and the smaller European countries, be something America and England had to reckon with. Vlasov's plan was to form an alliance with, among others the Chechs, Poles and Yugoslavs – and even cooperative Germans – to make a stand against the Red Army somewhere in Central Europe. After that, they could talk with the Americans, who undoubtedly would regard the liberation movement positively and would not repatriate the Russians to the Soviet Union, where certain death would await them. That is why Vlasov was very keen to prevent his divisions from being lost in the chaos of the last months of the war. Apart from that, Vlasov believed that the Americans would soon realize the criminality of the Stalinistic regime and would end the Soviet-American alliance immediately after the German capitulation.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The last months of the war

Vlasov eagerly awaited the moment that his divisions would be battle-ready, but their formation was hampered by bureaucracy, German lack of interest and above all lack of military equipment. Furthermore, Vlasov was actively opposed by opponents of the ROA among the German army leadership. Since Vlasov never showed his sympathy for the Nazy ideology in his manifestos and communiqués – Hitler, the National Socialism and the persecution of the Jews were never mentioned – the opponents doubted Vlasov’s loyalty. Was it sensible to arm such a person? Only on January 28, 1945, Vlasov was given supreme command over two divisions, a brigade and a small air force. There was no shortage of manpower, however, and the ROA would eventually grow to a 60,000 strong army. The last three months of the war would be marked by disagreements between the Germans and the Russians as to the deployment of the ROA units.

Major General Sergei K. Bunyachenko’s First Division, referred to by the Germans as the 600rd Infantry Division (Russian), was comparatively the best equipped. It consisted of "Osttruppen" and the remnants of the earlier mentioned Kaminski-Brigade, a total of 19,000 men. Some German generals were curious about the baptism of fire of the new First Division, so in April 1945, Bunyachenko received orders to transfer his division to the Oder front. This immediately resulted in a collision. An exasperated Bunyachenko indicated that it had been agreed that all ROA units would operate together under command of Vlasov and not under that of OKW. Oberführer Erhard Kroeger, Vlasov's SS liaison officer, succeeded in persuading the Russians in obeying the order, otherwise, the Germans might withdraw their support for the KONR-project or retaliate against Russian labourers of POWs. Finally, Vlasov and Bunyachenko reluctantly agreed. On April 14, the division received the impossible task of retaking a Soviet bridgehead on the Oder. The heavy artillery barrages and extensive barbed wire barriers proved to be too great an obstacle and without German permission, Bunyachenko decided to end the attack. The Red Army might launch its final offensive any moment and the general wanted to prevent his division from being decimated. General der Infanterie Theodor Busse of 9th Armee ordered the First Division to remain in their positions, but Bunyachenko decided on his own initiative to move his division southward to meet the other ROA units.

In Southern Germany, the First Division advanced through the sector of General Feldmarchall Schörner’s Heeresgruppe Mitte. Schörner, too, ordered the division to the front, but again, Bunyachenko ignored the German orders. He indicated that he only obeyed Vlasov's orders and marched on to the Czech Republic. In the meantime, Vlasov had sent various envoys, among others Strik-Strikfeldt, to the fast advancing American armies, but did not receive any response. Next, Vlasov marched with the incomplete Second Division of Major-General Grigory A. Zverev from Southern Germany to the Czech Republic to quickly assemble the entire ROA. Apart from that, Vlasov negotiated with various Cossack units in German service in an attempt to incorporate them in the ROA in the Czech Republic. Some Cossack formations eagerly joined their Russian brothers, but others did not agree with Vlasovs political ideas and decided to follow their own course. Meanwhile, various ROA officers tried to persuade Vlasov to flee while it was possible. A plane was waiting to take him to Spain, where Franco jhad offered him political asylum. Vlasov looked defeated but refused. "A leader who abandons his people at the critical moment, cannot be of any use any longer", he stated.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- persecution of the Jews

- "Judenverfolgung", action imposed by the Nazis to make life hard for the Jews, to actively persecute them and even annihilate them.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

The end of the war

American POW

On Mai 8, the ROA units were informed of the capitulation of Germany. The Americans had stopped their advance in the vicinity of Plzeň, 56 miles southwest of Prague. With the Red Army approaching, it was of ultimate importance for the Russians to reach the American lines as soon as possible. Vlasov drove ahead and surrendered to an American outpost. After a short interview with an American general, Vlasov was housed in the nearby castle Schlüsselburg (Lnáře). Here, the American commander of the town, Captain Donahue inquired after Vlasov’s motives in taking up arms against Stalin. Somewhat apathetic, Vlasov started to explain his position, Donahue however, appeared genuinely interested and in the course of Vlasov’s account, his passion returned. Donahue listened attentively, shook Vlasov’s hand and promised to do everything to prevent the extradition of ROA to the Soviet Union.

Bunyachenko surrendered to the Americans on May 11, in the vicinity of Schlüssselburg. They disarmed his First division and took Bunyachenko to the castle. Nearby Soviet tanks were reported, so Bunyachenko was keen on bringing his division within the American sector. However, he and Vlasov were told that the Russian military were not going to be interned by the Americans. During the afternoon of Mai 12, the two generals got into a jeep that was supposed to take them to the American army headquarters. Halfway, however, the column was stopped by units of the Red Army. A Soviet major attempted to arrest the two generals, on which Vlasov walked to the front of the column and emphasized the fact that he was an American POW. However, the American commander did not intervene. Vlasov en Bunyachenko were then taken by the Soviet Troops to a nearby headquarters and eventually transferred to the notorious Lublianka prison in Moscow.

Repatriation and Trial

Various delegates from the ROA requested American generals not to extradite Russian troops to Stalin. One of the envoys spoke to Brigadier Ralph Canine, Chief of Staff of the American XII Corps, about the fate of the 8,000 men of the ROA-air force under command of Major General Viktor I. Maltsev. Canine promised not to hand over the Russian to the Soviets. He did not keep his promise, however, and Maltsev’s men were eventually repatriated to the Soviet Union. Strik-Strikfeldt spoke to Lieutenant General Alexander Patch of the Seventh Army, who was sympathetic towards the Russian cause, but in this case as well, Washington decided differently. The already disarmed First Division was denied access to the American occupation zone. Nevertheless, parts of the division managed to escape to the American zone, as did the Second Division, the Reserve Brigade, the officers' school and the ROA staff. At least 10,000 men of the First Division, however, were murdered or deported by the Red Army. A good many Russians who managed to reach the American zone were later extradited to the Soviet Union, where they were executed or spent long periods in penal camps.

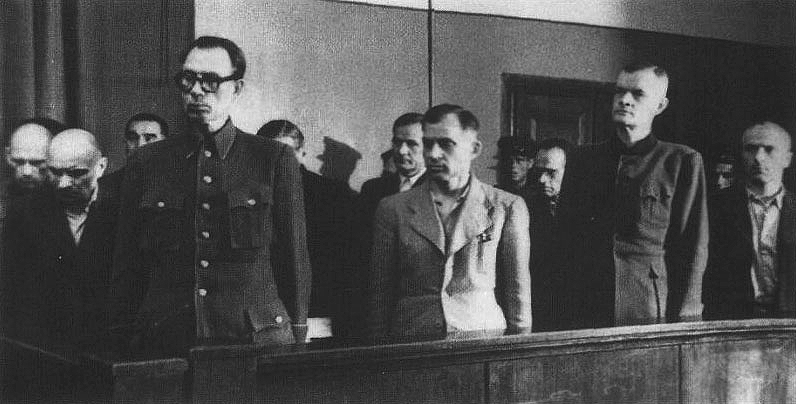

Vlasov, Bunyachenko, Zverev, Maltsev and five other ROA-generals were tried behind closed doors. The remaining transcripts of the trial are very subjective, politically biased and therefore unreliable, but it seems that Vlasov tried to take full responsibility, hoping that his friends would be punished less severely. It was to no avail, however. All the accused were charged with "high treason, espionage and terrorist acts in the service of German intelligence". Izvestia reported that all nine generals had been hanged. An eyewitness later declared that the executions were so gruesome, that he was unable to put the details into words.

Juridical unclarity

What Vlasov and his followers did not know, was that during the Jalta Conference, Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill had made agreements concerning the extradition of prisoners-of-war. One of the clauses prescribed that persons who were citizens of the Soviet Union on September 1, 1939, and had been captured, wearing German uniforms; on June 22, 1941, had served in the Red Army or, voluntarily, collaborated with the enemy, should be repatriated to the Soviet Union. That the forced repatriation of POWs was contrary to international law and the Geneva Convention was noticed by some lawyers, but ignored by the American and British authorities. Vlasov's own argument that his liberation movement was a political organization, whose members could not be tried according to military law, but should be entitled to political asylum, fell on deaf ears.

Opinions about Vlasov still vary tremendously. To many, it is clear that he was a defector, collaborator and traitor. Others oppose these three labels. Firstly, they claim, Vlasov was not a deserter, he was captured, being in a hopeless military situation. Furthermore, Vlasov did not cooperate with the Germans out of ideological convictions. He never expressed his support for the Nazi ideology; he even, however indirectly worded, rejected it. Various times, Vlasov openly indicated that he had no loyalty towards Nazy Germany. After the war, he was just as eager to cooperate with the Americans to reach his goals. The only reason for cooperating with the Germans was because he and the Wehrmacht had a common enemy and the Wehrmacht was capable of arming the ROA and occupied vast territories in the east – the most source of support for the Vlasov movement. And finally, supporters consider it important to nuance the term "betrayal". The Russian liberation movement acted out of anti-Stalinist convictions and therefore it was loyal to its homeland, but particularly not to the Stalinist regime. Seen in this light, Vlasov was more a Charles de Gaulle or a Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg than a Vidkun Quisling.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Information

- Article by:

- Auke de Vlieger

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- ANDREYEV, C., Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Movement, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987.

- BERKELAAR, W., De schaduw van de bevrijders, Walburg Pers, Zutphen, 1995.

- HOFFMANN, J., Die Geschichte der Wlassow-Armee, Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1984.

- KONYAYEV, N.M., General Vlasov, Veche, Moskou, 2008.

- KONYAYEV, N.M., Vlasov, Veche, Moskou, 2003.

- REITLINGER, G., The House Built on Sand, The Viking Press, New York, 1960.

- SHUKMAN, H., Stalin's Generals, Orion Publishing, 2002.

- STEENBERG, S., Vlasov, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1970.

- STRIK-STRIKFELDT, W., Against Stalin and Hitler, The John Day Company, New York, 1970.

- TOLSTOY, N., Victims of Yalta, Hodder & Stoughton, Londen, 1977.

- ANDREYEV, C., 'Andrei Andreyevich Vlasov', in H. Shukman (red.), Stalin's Generals, New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1993, pp. 11-23

- Final redaction by Anne Palmer.