Introduction

If one person could be associated with Nazi terror during the occupation of the Netherlands, it would be Hanns Rauter, the Höhere SS- und Polizeiführer and General Commissioner of security in the Netherlands. As the representative of SS-leader Heinrich Himmler, he was responsible for repressing the resistance, amongst other things, and he supervised the deportation of Jews. He was generally feared by the Dutch people and considered a symbol of oppression and terror.

This article describes the life of this prominent figure within the occupying forces in the Netherlands. At the same time, the outlines of the history of the Dutch occupation are addressed.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Early life, studies and the First World War

Hanns Albin Rauter was born on February 2nd, 1895, in Klagenfurt, the capital of the federal state of Carinthia in Austria. He was the second son in a family of seven children. His father, Josef Rauter, was a rather well-to-do chief forester, strongly oriented towards Germany.

After the young Rauter spent five years in the Volksschule (‘primary school’) in his place of birth, he went to the Realschule (‘secondary school’) in that same city and in Graz for seven years. He graduated in 1912. Afterwards, he took ten semesters in engineering at the Graz University of Technology. He wanted to become an Engineer, but had to temporarily abandon that plan because of the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. He quit his education and volunteered for service in the Austro-Hungarian army.

Rauter became an officer in the first Gebirgsschützenregiment (‘mountain protection regiment’) of Carinthia. He fought on the Isonzo and Piave front and later in Albania. During the four years of war, he gained experience as a liaison officer, adjutant to the district commander and company commander. In Albania, he was responsible for the formation of a corps of Albanian volunteers. His front service was interrupted in 1915 due to a serious injury caused by two machine gun shots in his thigh. He was nursed in Klagenfurt and Graz. Though Rauter was 35% war invalid after this, he saw no reason not to voluntarily return to the front. Near the end of the war he was injured again by a shot to the shoulder. When the war ended, Rauter had made his way up to the rank of Oberleutnant. For his bravery at the front, Rauter was awarded the Carinthia Bravery Cross, amongst other things.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

Freikorps service

The double monarchy Austria-Hungary ended after the defeat of the First World War. Austria became a republic which would persist until Germany annexed the country on March 12th, 1938. Like the Weimar Republic in Germany, the Republic of Austria was also afflicted with political turmoil. There was a lot of dissatisfaction with the defeat of the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles, and the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which determined that certain areas of Austria would be handed over to Czechoslovakia, Italy and Romania. Austria was also not allowed to enter in a political or economical union with Germany without permission of the League of Nation. This caused aversion amongst German nationalist movements who wanted Austria to join Germany completely.

There was especially a lot of dissatisfaction amongst veterans; many of them sought refuge in extreme right volunteer corps. These paramilitary units entered into battle with for example Jews, socialists and communists. The often unemployed and frustrated veterans accused them of being responsible for losing the war. Rauter also joined a Freikorps. Upon returning to Austria, he was disarmed by Left Revolutionairies at the station in Graz. He was put out over the chaos he came across. He called the demobilization a “disorganized collapse”. “When I wanted to be demobilized as an officer in Graz in November 1918, I was laughed at”, he explained. “In all of Austria, there was not one company. […] I believed in victory and it was hard having to give up my ideals.”

In Graz, Rauter became a member of a student volunteer corps and as company leader, he participated in battles with communists. He was active during the Carinthian struggle for independence. The Federal State of Austria was claimed by the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs – later known as Yugoslavia – and was partially occupied by them, resulting in armed conflicts with the Austrians. A plebiscite which resulted in the preservation of Carinthia within Austria ended this battle. Rauter was also active in a similar border conflict with the Poles in Upper Silesia in 1921. He was then a part of the Freikorps Oberland (‘Free Corps Oberland’).

Meanwhile in the Austrian state Stiermarken, the Steirische Heimatschutz, an extreme right paramilitary organization, was founded, and Rauter became a prominent member. “As opposed to the other associations, the Steirische Heimatschutz was dressed on an anti-Semitic basis,” described Rauter. “The regiments wore the swastika and the colors black-white-red. Fighting against Marxism and bourgeois democracy, bringing about an authoritarian state and joining the Empire were their objectives. […] In November 1922, the Obersteierische Heimatschutz took up arms for the first time against the then supreme Republikanischer Schutzbund [the social democrats’ paramilitary organization]. For the first time, we were able to push back Red.”

In the fall of 1921, Rauter was named Chief of Staff of the Steirische Heimatschutz. That year he also met Adolf Hitler, who was then still in the beginning of his political career. A second meeting occurred in 1927, and Walter Pfrimer, the leader of the Steirische Heimatschutz, was also present. “From this day on, there were good relations between the German Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the Steirische Heimatschutz ,” said Rauter. In the same year, Rauter had gotten involved in battles with social democrats who had rebelled in Vienna. Another important event he was involved in was the march from the Steirische Heimatschutz to Wiener Neustadt in 1928. The great Wiener Neustadt march, which I, as leader of the organization, led,” writes Rauter, “was a symbol for the strength of the Steirische Heimatschutz.” The confrontation of the Steirische Heimatschutz and similar movements from other Austrian federal states with the social democratic Republikanischer Schutzbund passed off without bloodshed, partly thanks to the efforts of the army.

Rauter must have felt at home during these years of political conflicts. After the march to Wiener Neustadt, he was named Chief of Staff of the cooperating Heimatschutzverbände (movements for protection of the fatherland). In 1931, Rauter and his supporters had to deal with two considerable setbacks. In September, the coup d’état led by Walter Pfrimer – the Pfrimer Putsch – in wich Rauter also participated, failed. Several participants of the Putsch were arrested and sued for high treason. That was a heavy blow for the Steirische Heimatschutz. Rauter also ended up in prison for a short time. Another setback for the movement was the fact that the cooperation with the other Heimatschutzverbände was put to a stop. The weakened organization now sought a rapprochement with the NSDAP, which was also active in Austria.

Definitielijst

- democracy

- From the Greek: demos (the people) kratein (rules). Democracy is a form of government elected by the majority of the people in which the people can check on the leaders and have the government resign in case a majority of the people no longer agrees with the government.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Freikorps

- German paramilitary units established directly after the Great War by former front soldiers. These groups were often named after their commander. Freikorps formed the basis of the eventual SA or Sturmabteilung.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Putsch

- Coup, often involving the use of violence.

- swastika

- Equilateral cross, symbol of Nazi-Germany.

- Weimar Republic

- Name for the German republic from 1919 until 1933. Hitler ended the Weimar republic and founded the Third Reich.

NSDAP, refugee aid and the transfer to the SS

It took until November 1933 for the Steirische Heimatschutz to fully merge with the Austrian NSDAP. In Germany, Hitler’s party was in control by now and they strove for Austria’s entry to the German Empire. The then Austrian government led by chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss opposed this. He attempted to stop the turmoil in his country by prohibiting the Austrian NSDAP and the social democratic parties. From that moment on, the Austrian NSDAP worked illegally. Austrian Nazis attempted a coup d’état on July 25th, 1934. Dollfuss was killed, but the coup failed. Dollfuss was succeeded by Kurt Schuschnigg, who resigned under severe pressure on March 11th, 1938. His successor was Arthur Seyss-Inquart under whose leadership Austria joined Germany that same month.

In the years from the prohibition of the NSDAP up to the Anschluss, Rauter made a career for himself within the German Nazi movement. He received German nationality, while his Austrian nationality was taken by the Dollfuss government. Nonetheless, he kept making efforts for the Austrian Nazi party. For example, he shortly commanded the Nationalsozialistischer Kampfring der Deutschösterreicher im Reich, the national socialist battle association of German-Austrians in the Empire. In 1935, he was named Chief of Staff of the Flüchtlingshilfwerk der NSDAP, the refugee aid of the NSDAP. This organization, for example, supported Austrian Nazis who had fled to Germany after the failed coup of 1934. They also smuggled money to Austria to support family members of arrested Nazis.

Rauter’s career within the German Nazi movement started in 1933 with the Sturmabteilung (‘Storm Detachment’; SA). His rank was SA-Standartenführer. On February 20th 1935, he transferred to the Schutzstaffel (‘Protection Squadron’; SS) in the rank of SS-Oberführer. He was recruited by Heinrich Himmler, the powerful leader of the SS, and he entered into his personal staff. He worked here from February 20th, 1935, until April 1936. After that, he was assigned to the SS-Hauptamt (‘SS Head Office’) from April to June 1936, and returned to Himmler’s staff until November 1938. From November 1st, 1938 until September 1st, 1940, he was staff leader of the SS-Oberabschnitt “Südost” (‘SS Senior District Southeast’), the main district of the SS in the southeast of the Empire with Breslau as its headquarters. Here he obtained “special merits […] for smoothly executing the action against the Jews in the night of November 9th to 10th, 1938 [that is, the Kristallnacht (‘Crystal Night’)].” On December 21st, 1939, Rauter was promoted to SS-Brigadeführer.

During his post as Leader of Staff of the SS-Oberabschnitt “Südost” , Rauter was temporarily appointed with both the Inspekteur der Sicherheitspolizei and the Inspekteur der Ordnungspolizei from February 1st, 1940 until March 31st, 1940. In Breslau and Kattowitz, he gained experience in the fields of various police and safety organizations of the SS, namely the Sicherheitsdienst (‘security service’), the Gestapo (‘secret state police’), the Kriminalpolizei (‘criminal police’), and the Ordnungspolizei (‘order police’). After gaining these experiences, he was ready for his next position; on June 26th, 1940, he was named Höhere SS- und Polizeiführer (HSSPF) “Nordwest” and leader of the SS-Oberabschnitt “Nordwest” (‘SS Senior District Northwest’). This northwestern main district of the SS consisted of, as of May 1940, the occupied Netherlands.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSDAP

- Nazi Party, byname of National Socialist German Workers' Party, German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), political party of the mass movement known as National Socialism. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler , the party came to power in Germany in 1933 and governed by totalitarian methods until 1945.

- Oberabschnitt

- Main district of the protection squadron (Schutzstaffel), the SS, from November 1933.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- Sturmabteilung

- Storm detachment. Semi-military section of the NSDAP. Founded in 1922 to secure meetings and leaders of the NSDAP. Their increasing power was stopped during “The night of the long knives”, 29 and 30 June 1934.

HSSPF: job description and position of power

In May 1940, the occupied Netherlands were subjected to a German civil government led by Reichskommissar für die besetzten Niederlande (government commissioner of the occupied Netherlands) Arthur Seyss-Inquart. As HSSPF, Rauter was subordinate to Himmler, but at the same time he was the subordinate of Seyss-Inquart as Generalkommissar für das Sicherheitswesen (commissioner general for security). Besides Rauter, Seyss-Inquart was aided by three other commissioners general. As Generalkommissar zur besonderen Verwendung (commissioner general for special occasions), Fritz Schmidt was responsible for directing the public opinion and the Nazification of the public life. As Generalkommissar für Verwaltung und Justiz (commissioner general for government and justice), Friedrich Wimmer was occupied with legislation and supervising the domestic government. In Seyss-Inquart’s absence, he was also his substitute. The fourth commissioner general was Hans Fischböck, who, as Generalkommissar für Finanz und Wirtschaft was responsible for finance and economic business. In the provinces and in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, Seyss-Inquart appointed Beauftragte, local supervisors. Military affairs were outside his immediate competence. Wehrmachtsbefehlhaber Friedrich Christiansen was entrusted with this task.

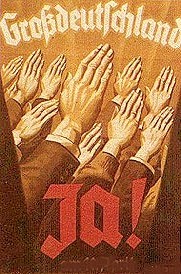

Seyss-Inquart and his commissioners general took the place of the government and the parliament. They supervised and gave orders to the bureaucracy which remained intact and now worked according to German guidelines. An important objective of the occupying government was to make the Dutch people enthusiastic for National Socialism. The Dutchmen were considered their brother people and they had to strive for the annexation of the country to Greater Germany. Another objective was to place the Dutch economy in service of the German war economy. Eventually, it would turn out that at least the first objective resulted in failure. The Dutch people, apart from a minority, were not open to a far-reaching rapprochement to Germany.

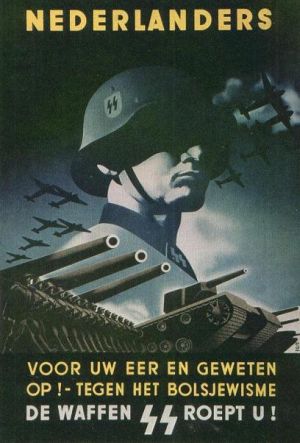

Rauter’s position of power in the Netherlands was comprehensive. As HSSPF and commissioner general he was the main person responsible for all SS- and police activities in the Netherlands. He did not only supervise the German SS- and police services, among which the Sicherheitspolizei (‘security police’) and the Ordnungspolizei (‘order police’), but the Dutch police was also under his supervision and was reorganized by him. He acted as the eyes, ears and spokesperson of Himmler in the Netherlands and he supervised and coordinated plenty of activities of the SS in political, ideological, police and military areas. The national and regional commanding officers of the Sicherheitsdienst (‘security service’), the Sicherheitspolizei, the Waffen-SS and the Ordnungspolizei were subordinate to Rauter and were to keep him informed of their activities. He also had a part in the recruitment of Dutch volunteers for the Waffen-SS. An important responsibility of the HSSPF was also the coordination of large operations in which multiple SS- and police bodies were involved, like the suppression of large strikes. For his work, he was in contact with Himmler, but also with the various SS headquarters, such as the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA).

Though Rauter was formally subordinate to two bosses, he was most committed to Himmler. He was already impressed by the SS leader when they first met. He signed his letters to Himmler with “Heil Hitler! Your with great compliance subservient Rauter” and in April 1942 he wrote to him: “I do believe I am allowed to say that I have looked after your interests in a way no one else could have done any better [...]”. Himmler, for his part, was satisfied with his compliant and loyal subservient in the Netherlands. “Dear Rauter,” he wrote in February 1944, “I express my full appreciation to you and your fellow workers for the community work executed in the past two years in the Netherlands, which constitute a clear progression on the way to the Germanic empire and the Germanic community.” He received special appreciation for, for instance, the concentration camp Vught and the training school for the Dutch SS in Avegoor. Rauter was promoted three times during his appointment in the Netherlands: on April 20th, 1941 to SS-Gruppenführer; on June 21st, 1943 to SS-Obergruppenführer and on July 1st, 1944 to General der Waffen-SS und der Polizei.

Himmler’s orders may have come first, but nonetheless Rauter had to consider his second superior, Seyss-Inquart. Seyss-Inquart was a strategic politician and an intellectual with a great interest in art and culture, while Rauter was above all a soldier with no intellectual interests. His relation to Seyss-Inquart was not as good as the one with Himmler, though their working relationship generally went without large problems. This was probably because the rough, aggressive SS member was no match for the intellectual and political discretion of the Reichskommissar. Still, there was at least one time when their relations were strained, namely in the beginning of 1943 because of the attempts of Generalkommisar Schmidt to expand the role of NSB leader Anton Mussert within the rule of the country. Rauter strongly opposed this. Rauter was almost relocated to Poland in the Generalgouvernement to switch posts with SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Krüger who was involved in a similar conflict with Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. The relocation never happened, because Seyss-Inquart and Rauter were able to appease their conflict. In the end, the departure of the HSSPF was of no avail to the Reichskommissar, because he carried out his work satisfactorily. Rauter himself probably did not look forward to a departure to Poland either, because Poland was much less peaceful than the Netherlands at that time.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- Greater Germany

- “Grossdeutschland”. A Germany with boundaries enclosing all German speaking people. Aim of the Nazis.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- Reichskommissar

- Title of amongst others Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the highest representative of the German authority during the occupation of The Netherlands.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

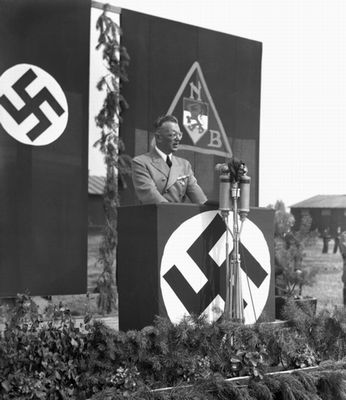

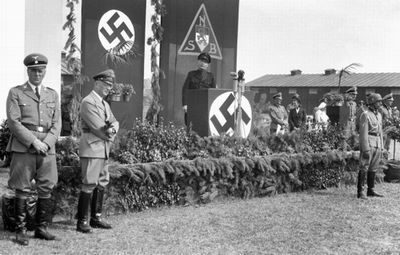

Images

Government commissioner Arthur Seyss-Inquart speaks to newly sworn-in men of the ‘Landwacht’ in Weert. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Government commissioner Arthur Seyss-Inquart speaks to newly sworn-in men of the ‘Landwacht’ in Weert. Source: ANP Photo Archive. Rauter and Mussert were also present at this oath ceremony. Rauter is the one on the left and Mussert is speaking. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Rauter and Mussert were also present at this oath ceremony. Rauter is the one on the left and Mussert is speaking. Source: ANP Photo Archive.Aversion to Mussert and the Diets notion

The pursuit of the Netherlands’ entry to Greater Germany was an important goal of Himmler, and thus also of Rauter. This objective was not supported by Anton Mussert, leader of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB). He aimed for a Greater Dutch ideal, meaning the Netherlands and Flanders would be combined to a so-called Greater Dutch empire, under influence, but not under control of, the German rule. Rauter did not care much for Mussert and not at all for his Greater Dutch ideas. He constantly made sure that the power of the NSB leader remained limited. For example when Rauter ordered the CID to be closed down. This was the Central Information Office of the NSB, which occupied itself with giving information on NSB members, but also on political subjects within the Dutch society. Especially the latter was not much to the liking of the higher SS and police leader, because political information was the field of the information office of the SS, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD). He also suspected the leader of the CID to be an agent of the British secret service. After de CID was closed down by Rauter, all that was left was the department which occupied itself with collecting information on (aspirant-) members, the General Member Supervision.

How SS people looked at Mussert, is shown in the weekly magazine ‘Storm’ of the Nederlandsche SS (‘Dutch SS’) of March 7th, 1944. On the occasion of the NSB leader's birthday, a picture page was dedicated to him. The birthday boy did not feel honored though, because they deliberately printed several photographs which ridiculed him. One picture, for example, showed how he, as a child, was taken by the arm by Himmler. Another picture showed Mussert and several people he had kicked out of the party before. It was under the influence of his fellow party members, Rost van Tonningen and Henk Feldmeijer, that the weekly magazine increasingly criticized his leadership. Both men represent the more radical section of the NSB which did not strive for the realization of a Greater Dutch empire, but for the annexation of the Netherlands to Germany. They, then, were able to count on the appreciation of Rauter and the SS.

The before-mentioned conflict of Rauter with Seyss-Inquart over the tensions of Generalkommissar Schmidt to give Mussert an important role in the country's rule shows Rauter’s aversion to the NSB leader and the Greater Dutch vision. This conflict occurred in the beginning of 1943, but has its origins before that. In August 1942, Martin Bormann issued a party instruction by Hitler which ordered that Himmler’s SS needed to supervise the Dutch people who stood willingly with respect to the German occupier. This meant that Rauter, as representative of Himmler in the Netherlands, received a larger political role and was able to exert influence in the field which previously belonged to Schmidt for the main part. He was responsible for directing the public opinion and the Nazification of the public life. His attempts to defend his position of power against the SS were in vain. He died on June 27th, 1943, probably by suicide, though some including Mussert and the underground magazines in that time believed that he was murdered by the SS. To suppress all doubts, Himmler ordered Rauter to be present at the memorial service. But Rauter would not have mourned Schmidt for a minute, because an important obstacle was now cleared.

Definitielijst

- Greater Germany

- “Grossdeutschland”. A Germany with boundaries enclosing all German speaking people. Aim of the Nazis.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

Images

Anton Mussert, leader of the National Socialist Movement (NSB). Source: STIWOT Archive.

Anton Mussert, leader of the National Socialist Movement (NSB). Source: STIWOT Archive. Anton Mussert congratulates Dutch Obersturmführer Wim Heubel on his award of the Iron Cross. Rauter is on the right. Heubel was the brother of Florrie Rost van Tonningen-Heubel, also known as the Black Widow. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Anton Mussert congratulates Dutch Obersturmführer Wim Heubel on his award of the Iron Cross. Rauter is on the right. Heubel was the brother of Florrie Rost van Tonningen-Heubel, also known as the Black Widow. Source: ANP Photo Archive.Symbol of oppression and terror

During the years of occupation, Rauter became a symbol of oppression and national socialist terror to the Dutch people. Rauter was the one who, through his Bekanntmachungen (announcements), kept the Dutch informed of all kinds of sanctions taken within the framework of safety, such as the promulgation of the police summary jurisdiction on May 1st, 1943 after the April/May strikes and the fusillade of resistance fighters. His name was mentioned in newspapers and he could be seen in propaganda films in cinemas when they reported on his public appearances, often in the company of Arthur Seyss-Inquart or Anton Mussert. He appeared, for example, at the waving goodbye of the Dutch Waffen-SS volunteers who left for the eastern front, and at takings of oath and inspections of the ‘Landwacht’, an assistance police made up mainly of members of the NSB. Rauter stood out on pictures and film images because of his tall figure and military appearance. The scars on his face, remains from fencing duels during his college years, gave him a violent look. Historian Loe de Jong claims the Dutch feared Rauter. “Many jokes were made about Seyss-Inquart, but not one about Rauter,” he said.

Rauter was a prominent representative of the occupying force, not only on paper, on screen and in the public opinion, but especially in practice. He was intensively involved in all sorts of important measures taken to oppress the Dutch people and the resistance. Until 1944, he played an influential role in, for example, oppressing the February strike and the April/May strikes, and organizing the Operation Silbertanne (‘Silver Fir’). In that time he also had a mainly supervising role in executing the deportation of Jews in the Netherlands to concentration and destruction camps in the east.

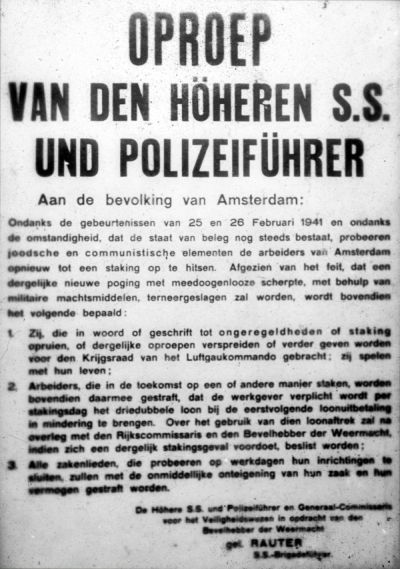

The February strike took place on February 25th and 26th, 1941. Before this, since the end of 1940, multiple fights broke out mainly in the big cities between Dutch people and members of both the resistance department WA, the paramilitary organization of the NSB, and the National Youth storm, a Dutch youth organization after the example of the German Hitler-Jugend. These movements which were on the German side provoked other Dutch people by massively going out into the streets to show their power and massiveness, just like the Sturmabteilung (SA) did in Germany around the time of the assumption of power. Their provocation in Amsterdam was mainly aimed at the sizeable Jewish population of the capital. Especially in the area of the Waterlooplein, they pushed their way into Jewish people's houses and cafés and destroyed the inventory. Early 1941, the terror in the streets increased in violence and the Jews, supported by non-Jewish citizens of Amsterdam, defended themselves fiercely. On February 11th, the Amsterdam NSB member Hendrik Koot was so badly hurt in fights that he died a couple of days later and on February 19th, a patrol of the Ordnungspolizei walked into an ambush which was actually meant for members of the NSB at ice-cream parlor Koco. A policeman was sprayed in the face with ammonia from a bottle which one of the owners of the parlor had opened before leaving the building. Rauter reported both incidents to Himmler, making sure he exaggerated the facts. “When the officers entered the room, they were immediately sprayed in the face with ammonia and they were shot at,” he said about the incident in ice-cream parlor Koco. On the death of Koot he claimed the following: “A Jew had jumped him from behind, bit through his artery and sucked his blood.”

As a result of these and other incidents, Himmler, Rauter and Seyss-Inquart decided upon a tough approach; the first round-up became a fact on February 22nd and 23rd. To set an example, a total of 427 Jewish men between twenty and thirty-five years old were sent to camp Schoorl. Out of anger about this, but also because of the dissatisfaction which was already present for a long time within the worker community, the illegal Communist Party of the Netherlands called for a large-scale strike on February 25th and 26th to which people massively replied, both in Amsterdam and in other Dutch cities. This was the first time such a massive protest against the German occupier happened. They did not hesitate to take action; many strikers were arrested and they were even shot at, causing some to die. On the second day of the strike, order was restored. The impact of the incident was rather large, because now that the occupiers were confronted with such a resistance, their policy became tougher in comparison to the first months of occupation, which passed relatively quietly. When Rauter rightly expected another strike on March 6th, he called to the people of Amsterdam and declared: “Those who incite to disturbances or strikes, orally or in written, [...] will be court-martialed at the Luftgaukommando; they are risking their lives.” Rauter had SS troops ready to interfere that day, but it remained quiet everywhere.

On April 29th and 30th 1943, strikes started again in many Dutch places. This time, the announcement of the Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Friedrich Christiansen saying that all former soldiers of the Dutch army still had to be taken into captivity immediately, was the cause. The aim was to put these militaries to work in Germany in the Arbeitseinsatz (‘labor deployment’) and at the same time rid the Netherlands of able-bodied men who might join the Allies in a possible invasion. The announcement caused widespread dissatisfaction and the strike which started in a machine factory in Hengelo, caught to almost everywhere in the Netherlands, though it remained relatively quiet in Amsterdam because the oppression of the February Strike had made a deep impression. Now though, the occupying force acted even tougher than in February 1941, to prevent the strikes from catching to other occupied countries.

On May 1st, Rauter proclaimed the police summary jurisdiction. “The SS and police units subordinate to me will shoot immediately and without a warning when gatherings of any kind take place, or when more than five people gather in public roads or squares [...],” he warned the Dutch population. It was also prohibited “to loiter in the open air between 20.00 and 06.00 hours.” The tough oppression of strikes had its necessary effect. The strikes were put down with shoot-outs, arrests of random strikers and summary executions and on May 3rd most strikers were back to work. A total of nearly 140 Dutch people died. The April/May strikes were a definite change in the history of the German occupation of the Netherlands. The Germans found out that the Dutch would not be conquered easily and increasingly reverted to intimidation and violence to oppress the Dutch people. At the same time, the willingness of the Dutch to resist increased. The German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943 and the hope for an allied invasion gave them renewed courage, while these were reasons for the Germans to treat the Dutch more hostile and to give priority to the war efforts over the annexation of the Netherlands to Germany.

Meanwhile, the Dutch resistance also took to tougher actions. In 1943, members of the resistance attacked several collaborators including general Hendrik Seyffardt, the founder of the Voluntary Legion of the Netherlands. He died of his injuries on February 6th, 1943. Both Mussert and Seyss-Inquart considered avenging the assaults with shooting anti-German Dutch people, but both feared this would only lead to more resistance. When the number of armed resists against collaborators increased in the course of the year, Rauter was the one to aim at an unrelenting response. Though he claimed that it was NSB member Henk Feldmeijer’s idea after the war, he was the driving power behind the plan to avenge every assault by the resistance with the murder of three anti-German Dutch people. The operation came to be known under the code name Silbertanne and was executed by Dutch members of the SS of the Sonderkommando Feldmeijer, supported by the Sicherheitsdienst which provided cars with fake license plates and fake identity cards, because no one could know who executed these actions. A total of over fifty Dutch people were killed as part of this Aktion.

Besides oppressing the Dutch population and the resistance, Rauter was also involved in the persecution of the Jews. On June 30th 1942, in a regulation for the isolation of Dutch Jews, he announced a series of measures aimed at excluding the Jews in the Netherlands from the social life. From that moment on, Jews had to, for example, “remain in their residences between 20.00 and 06.00 hours" and they were forbidden to “loiter in residences, gardens or other private institutions for recovery or relaxation owned by non-Jews [...]”. “Entering railroad yards and using all public and private vehicles” was no longer allowed for Jews. Shortly after this, the deportations to concentration and extermination camps in the east began, which mostly ran through the transit camp Westerbork. A total of around 107.000 Jews were deported from the Netherlands. About 102.000 of them were murdered.

The deportations were executed by the Referat IV B 4 in The Hague under the command of the Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD. Between July 1940 and September 1943, SS-Gruppenführer Dr. Wilhelm Harster performed this function. The assignments as part of the deportations to the east did not come from Rauter, but from the office of the same name in Berlin under control of Adolf Eichmann. The Dutch department of the Referat IV B 4, in its turn, gave instructions to the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung (central office for Jewish emigration) where SS-Hauptsturmführer Ferdinand Aus der Fünten was in charge. Both the Referat IV B 4 and the Zentralstelle were a part of the SS in the Netherlands and were thus under Rauter's supervision. He supervised the deportations and reported to Himmler. He had no doubts about the usefulness of the deportations; he was a whole-hearted anti-Semite and he was convinced that “removing” Jews was necessary.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- February Strike

- Anti-German demonstration in the Netherlands during 25 and 26 February 1941. Direct cause was the violent razzia by the WA and German soldiers in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- National Youth storm

- Dutch youth organisation of the NSB for Dutch boys and girls aged 10 to 18 years. Sport played an important part in the organisation.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- persecution of the Jews

- "Judenverfolgung", action imposed by the Nazis to make life hard for the Jews, to actively persecute them and even annihilate them.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Sturmabteilung

- Storm detachment. Semi-military section of the NSDAP. Founded in 1922 to secure meetings and leaders of the NSDAP. Their increasing power was stopped during “The night of the long knives”, 29 and 30 June 1934.

- WA

- Abbreviation of defence department, assault groups of the NSB

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Images

Rauter’s appeal to the people of Amsterdam after the February strikes. Source: Resistance Museum Amsterdam.

Rauter’s appeal to the people of Amsterdam after the February strikes. Source: Resistance Museum Amsterdam. Departure of the first contingent of Dutch volunteers to Russia on July 26th, 1941. Rauter and lieutenant-general Hendrik Seyffardt inspect the men in the great hall of the Hague zoo. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Departure of the first contingent of Dutch volunteers to Russia on July 26th, 1941. Rauter and lieutenant-general Hendrik Seyffardt inspect the men in the great hall of the Hague zoo. Source: ANP Photo Archive. Farewell of Dutch volunteers leaving for the eastern front on March 3rd, 1942. Rauter and Mussert are present. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Farewell of Dutch volunteers leaving for the eastern front on March 3rd, 1942. Rauter and Mussert are present. Source: ANP Photo Archive. Rauter and Mussert during an inspection of the ‘Landwacht’ at the Malieveld in The Hague, July 13th 1943. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Rauter and Mussert during an inspection of the ‘Landwacht’ at the Malieveld in The Hague, July 13th 1943. Source: ANP Photo Archive. Jews at the loading platform in camp Westerbork. A total of approximately 107.000 Jews were deported from the Netherlands. Source: USHMM.

Jews at the loading platform in camp Westerbork. A total of approximately 107.000 Jews were deported from the Netherlands. Source: USHMM.Dolle Dinsdag, total terror and the assault

After the allied landings in Normandy on June 6th 1944 and the liberation of Paris by the end of August, the allied march went off well. After Antwerp also fell in allied hands on September 4th, panic broke out amongst the German occupying force and their collaborators; they feared the Netherlands too would soon be liberated by the Allies. Seyss-Inquart and Rauter declared a state of national emergency. Rauter stated “that it is prohibited to be in the open air between 20.00 and 04.00 hours. Gatherings of more than five people, of any kind, will be shot at by patrols of the Weermacht, the SS and the Police. The Weermacht and the Police will also shoot at anyone who, at a time when it is prohibited, is in the open air and does not stop at the first command.” This emergency measure only caused more panic amongst collaborators. On September 5th, they massively fled while other Dutch people prepared to greet their liberators in a festive mood. On September 12th, American troops did set foot on Dutch soil in South Limburg, and on September 13th and 14th Maastricht was the first city in the Netherlands to be liberated, but the major part of the Netherlands had to wait months for liberation. Between September 17th and 25th, the Allies attempted to move on to Arnhem from the Dutch southern border to then invade Germany with operation Market Garden. However, this operation failed. Meanwhile, Rauter was named General der Waffen-SS und Polizei and during the Battle of Arnhem he commanded the Kampfgruppe. Rauter was put to action in operations in the Veluwe and the IJsselbruggen.

After the proclamation of the state of national emergency, the influence of the Wehrmacht on the occupying rule increased. Especially in the larger cities, Dutch men were arrested by the German army to be put to work, for example, at the lines of defense. They were supported by an announcement of Rauter of September 16th in which he informed that “The German SS and police formations, including the Arbeitskontrolldienst and all of the Dutch police [...] received the assignment to immediately arrest 16 to 50 year old Dutch people in cities and villages, streets and squares, who apparently have nothing to do and spend their time loafing about, and to take them to the employment camp in Amersfoort. There, they will be put at the disposal of the employment offices in Germany.” In the west of the Netherlands and in the Noordoostpolder at least 120.000 men were arrested to be employed.

Under the influence of the allied progressions and the increased resistance among the Dutch people, the occupying police became more and more vicious: Rauter reverted to total terror. In the summer of 1944, Hitler issued the Niedermachungsbefehl which stated that the arrested resistance fighters no longer had the right to a trial: resistance fighters who were armed when they were arrested, could be executed on the spot or turned over to the Sicherheitspolizei. That organization could decide which detainees would be fusilladed. From the fall of 1944 onwards, fusillades generally did not take place in remote locations anymore, but in public, next to roads and on squares. The bodies often remained there for one or several days to intimidate passers-by. Another means of intimidation was threatening to execute innocent hostages.

Harsh reprisals were now taken on actions of resistance, in which innocents were punished. On October 1st in Putten, for example, several men were executed as a reprisal for an assault to a German army vehicle; another 600 men were transferred to concentration camp Neuengamme and only several returned alive after the war. The order for the round-up in Putten was not issued by Rauter, but by Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Friedrich Christiansen, though it probably was Rauter’s idea to transfer the entire male population of Putten between 18 and 50 years old to a concentration camp. A few months later, another horrible reprisal took place. Again, Rauter did not give the order, but he played an important part in this history.

In the night of March 6th to 7th 1945, Rauter was seriously injured in an assault [see: inadvertent attack on Rauter]. During the car ride from his headquarters in Didam to Apeldoorn, he was shot at by resistance fighters near Woeste Hoeve. It was an unintentional assault on his life, because the resistance fighters actually wanted to stop a truck of the Wehrmacht. With that truck, they wanted to collect three thousand kilos of meat which were waiting for the Germans at a slaughterhouse in Epe. At the unexpected meeting, Rauter’s driver and another officer were instantly killed. Rauter was hit by multiple bullets and left there to die. It was not until the next day that he was found and taken to a German military hospital where he received two blood transfusions. As a reprisal for this unintentional assault, 274 Dutch people were executed by order of SS-Brigadeführer Eberhard Schöngarth, the Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD in the Netherlands since June 1st, 1944.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Rauter’s transport, an open BMW, after the assault in the night of March 6th to 7th, 1945. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Rauter’s transport, an open BMW, after the assault in the night of March 6th to 7th, 1945. Source: ANP Photo Archive. Reconstruction of the assault to Rauter. Source: ANP Photo Archive.

Reconstruction of the assault to Rauter. Source: ANP Photo Archive. Monument near the place where 117 Dutch people were executed as a reprisal for the attack on Rauter. Source: René ten Dam.

Monument near the place where 117 Dutch people were executed as a reprisal for the attack on Rauter. Source: René ten Dam.Apprehension and punishment

Even before Rauter healed from the injuries he sustained during the assault, he was arrested by British troops in a German hospital on May 11th, 1945. On February 6th, 1946 he was handed over to the Dutch government to be tried for committing war crimes. From February to October 1946, he was remanded in Scheveningen and in November and December in Rotterdam. At that point, he was still at the disposal of the Bureau Nationale Veiligheid (‘office of national security’) and the Bureau Opsporing Oorlogsmisdaden (‘office tracing war crimes’), but in December 1946 he was handed over to the public prosecutor at the Bijzonder Gerechtshof (‘special court’) in The Hague. During the first months of 1947, Rauter stayed in the Arnhem prison for giving depositions in the case against Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Friedrich Christiansen who was sentenced to 12 years of imprisonment, but was eventually already released in 1951.

During his own trial, Rauter stayed in the prisons of Rotterdam and Scheveningen. On February 5th 1947 K. van Rijckevorsel was assigned as his lawyer after his previous defender was already released of his duty after two weeks. The trial against the former Höhere SS- und Polizeiführer began on April 1st, 1948. The presiding judge of the lawsuit was Jhr. Mr. P.G.M. van Meeuwen and the Openbaar Ministerie (‘public prosecution service’) was represented by public prosecutor Mr. J. Zaaijer. Because he had played the same part in previous trials against Anton Mussert and Nazi-propagandist Max Blokzijl, Zaaijer was nationally known. Both Mussert and Blokzijl were sentenced to death. It was really already evident that Rauter would receive the same punishment; he personified the crimes of the occupying government and there was no way to deny his responsibility in terror measures against innocent hostages and his supervising part in the persecution of the Jews, amongst other things. Zaaijer then characterized the case against Rauter as a show case. The trial received a lot of attention of the Dutch press who, in their articles, referred to Rauter as Jew Exterminator, the second Alva, supreme executioner and vulture of the Alps. Even historian Loe de Jong would later use similar names in his publications. For example, he referred to Rauter as gang leader, scarecrow and bandit captain.

The accusation against Rauter was summarized by Zaaijer in seven main points: the persecution politics against the Jews, the carrying away of workers to Germany, the systematic robbery of the Dutch population, the confiscation of radios, the apprehension and deportation of Dutch students, coercive measures against family members of police officers in hiding and the reprisal measures against Dutch civilians, including Operation Silbertanne. Called as witnesses were, for example, Joseph Schreieder, the former chief of the department Amt IV E of the Sicherheitsdienst in The Hague, and NSB member Cornelis van Geelkerken.

During the trial, Rauter played down his involvement in the persecution of the Jews. He maintained he knew nothing about the fate which awaited the Jews in the east. He did take the final responsibility for fusillading hostages and resistance fighters, but stated that he was not responsible for the other work of the Sipo and SD. “I only did what I was told to do,” he claimed during the trial. “I do not feel guilty. I am not a war criminal.”

Rauter was sentenced to death on May 4th, 1948. He appealed to the court of cassation on May 12th, 1948. The case was tried for the Bijzondere Raad van Cassatie (‘special court of cassation’) on October 20th and 22nd, 1948 in the building of the Hoge Raad (‘supreme court’) of the Netherlands. The death sentence was confirmed on January 12th, 1949. Rauter’s legal adviser then filed a petition for revision at the Bijzondere Raad van Cassatie, but the request was denied in March 1949. The filed petitions for clemency were also denied with Koninklijk Besluit (‘royal order’). Nothing could prevent Rauter from being executed by a firing squad in the Scheveningen dunes in the morning of March 25th, 1949. There was some commotion in the media about how this happened. The Gooi- en Eemlander wrote that Rauter kneeled before the execution and said a short prayer. “After that he put on his gloves and hat and ordered the firing squad with an unaffected voice: Feuer.” A commentator of De Tijd reacted furiously several days later. He was “amazed” at this “distortion of honor”, this “permission for suicide”, which was “completely in line with the National Socialist ideology.” Rauter’s body was buried unnamed at a German soldier cemetery.

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- persecution of the Jews

- "Judenverfolgung", action imposed by the Nazis to make life hard for the Jews, to actively persecute them and even annihilate them.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Sipo

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Kim van Dijk

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- GERRITSE, T., De ploert Hanns Albin Rauter en de correcte ambtenaar Wilhelm Harster, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2006.

- JONG, L. DE, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 4, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1969.

- KOK, R. & SOMERS, E., Nederland en de Tweede Wereldoorlog, 2005.

- PIERIK, P., Van Leningrad tot Berlijn, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2006.

- Simon Wiesenthal Center, Documentatiemap Rauter

- Nederlanders in de Waffen-SS

- Axis Biographical Research

- Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive at USHMM