Introduction

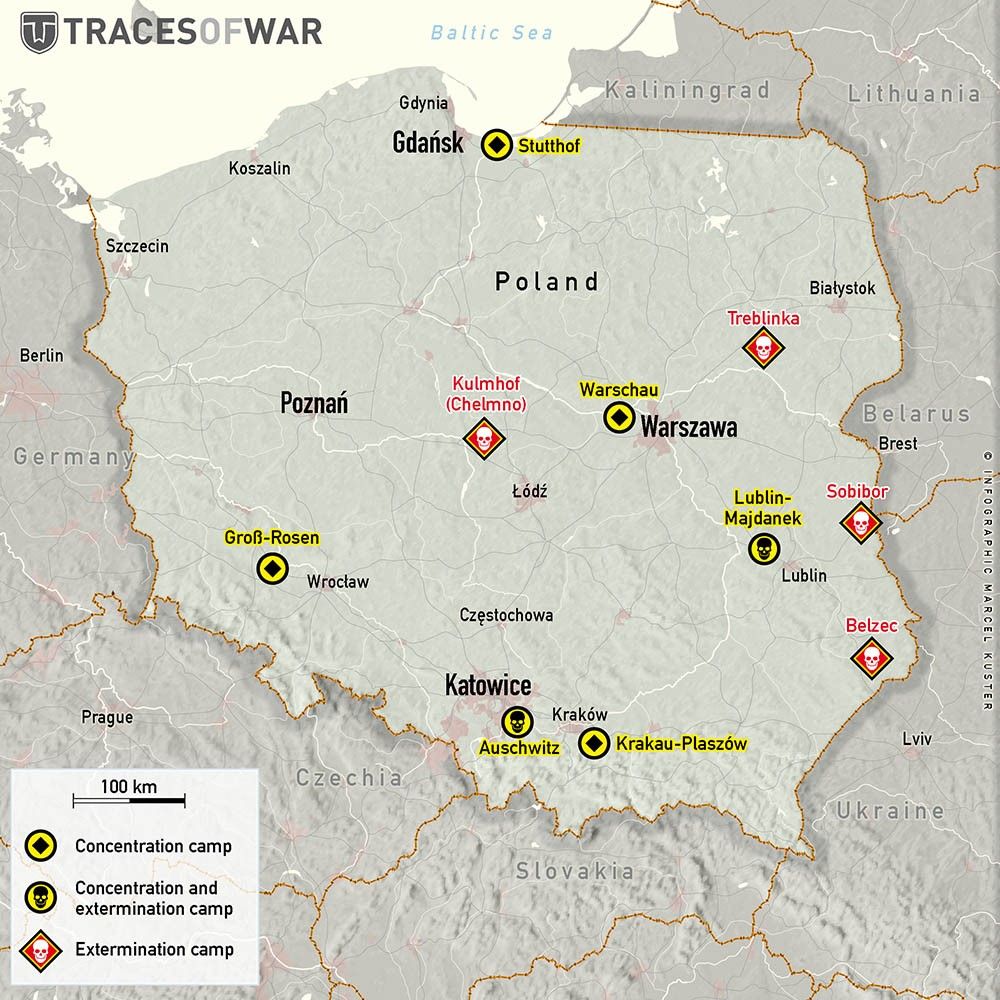

In September 1939, the German army invaded Poland. The Poles could not cope with the German attacking power and were forced to retreat time and again. During their withdrawal, they destroyed as many bridges as possible to slow the advance of the Wehrmacht. That way, they also blew the bridge across the Sola near Oswiecim. Their efforts were in vain as the German troops advanced relentlessly. At the end of September Oswiecim was captured. The synagogue was burned down but would be rebuilt in 1941. In October 1939, certain parts of Poland, including Oswiecim and surroundings, were absorbed into the Third Reich. The name was changed to Auschwitz. The hitherto unknown small town was to play a role in the coming years that would evoke sentiments of horror for years afterwards.

Definitielijst

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Concentration camp Auschwitz

On February 21, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was notified about empty Polish army barracks being available in Auschwitz. To the inspector of concentration camps, SS-Oberführer Richard Glücks and Erich von dem Bach-Zalewski, Höhere SS- und Polizeiführer in Silesia, this appeared to be an ideal location to establish a concentration camp. Rudolph Höss, commander of concentration camp Sachsenhausen visited the site and issued a positive report. There were lots of room: 20 buildings including 14 with one story and six with two. They were situated well outside the city center, so expansion would not pose a problem and the camp was shielded from prying eyes. Thanks to the good railway infrastructure and the central location in the part of Europe captured by the Germans, prisoners from the entire Reich could easily be transported to this location.

Based on Höss’ report, Himmler ordered the establishment of a camp on April 27, 1940. Erecting a camp was necessary as the prisons in Silesia were all overcrowded. Moreover, further arrests among the Silesian population and in the Polish areas within the General Government would follow. The new concentration camp was originally intended to make a contribution to the "Germanizing of the East". The prisoners were to drain the swamps and lay out fertile fields where German colonists could settle.

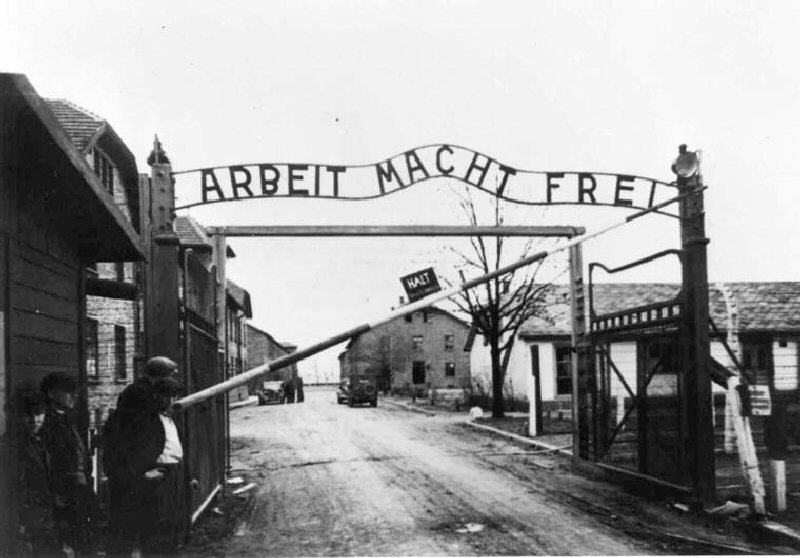

On May 4, 1940, Rudolph Höss was named the first commander of the camp. He was to turn the camp into an orderly concentration camp. In memory of his school in Dachau, he had the slogan Arbeit macht Frei (Labor liberates) placed over all entries of the camp. Yet, it was not Höss’ intention to make Auschwitz into a second Dachau. The attitude towards Jews and other undesirable elements in Nazi society had changed in the meantime and this made Höss take a different attitude towards his inmates than his tutor Eicke. To Eicke, his prisoners were enemies of people and state but Höss took it a step further by branding his inmates as harmful elements within German society. Höss’ policy therefore was far more directed at elimination and the extermination of these harmful elements was exactly Himmler’s goal with Auschwitz.

The first 30 prisoners, all of them criminals from Sachsenhausen, arrived on May 20, 1940. According to the Höss policy of divide and rule, they were deployed as guards or Kapos. They did not have to do labor themselves but had to supervise the work of the other inmates. They often treated their fellow prisoners far worse than the SS guards did as they received special privileges because of their work as guards and maybe even could prolong their lives. Höss managed to introduce a cruel regime in the camp whereby victims often became perpetrators.

Three weeks later, on June 14, 1940, the first transport of Polish prisoners arrived, consisting of politicians, resistance fighters, clergy men and Jews. Karl Fritzsch, Höss’ right hand man made it clear to the first prisoners of Auschwitz they were never to leave the camp, unless through the chimney.

Meanwhile, the firm Topf und Söhne had started construction of the first cremating ovens. With these, the expected large number of corpses could disposed of quickly. At the end of July, the ovens were ready and cremation could begin. 70 corpses could be cremated each day. That was necessary as the number of prisoners, and consequently the number of corpses began to increase fast. In 1941, another two ovens with double doors were installed. The camp was expanded gradually, a floor was added to each one story building and eight new ones were constructed. Blocks 10 and 11, together the notorious death row, were attended to as well.

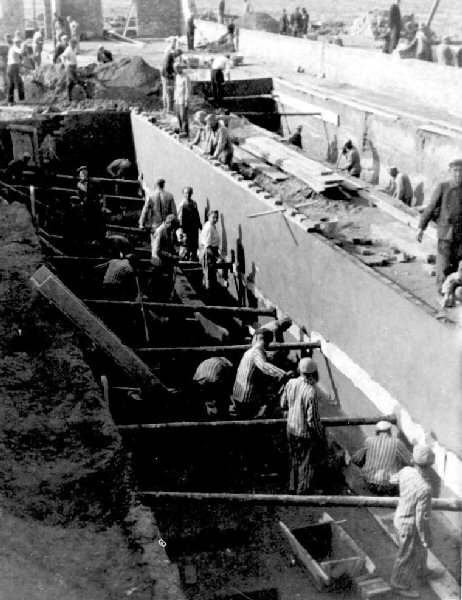

The inmates were to do hard labor: it was not intended anyone should leave Auschwitz alive. They had to dig deep ditches around the premises so no one could leave the camp unnoticed. While the inmates were at work, they were often kicked and beaten. Whoever fell or could not keep up with the rest was shot. Even the death block claimed many victims. Block 11 housed the camp jail. Any one caught stealing for instance, ended up here. Just being a Jew or a priest was sufficient as well. Characteristic for this jail were the stand-up cells: three to four people were crammed together in a space hardly larger than a phone booth. Sitting or even squatting was impossible. In winter it was ice cold inside and many prisoners froze to death. Whoever survived the stand-up cell was usually executed against the wall between Blocks 10 and 11.

In Block 11, the first gassings were also carried out. Executing and hanging were not sufficient any more. The SS looked for more expedient ways to exterminate the prisoners. Moreover, continuous executions were a severe mental burden for the men of the firing squads. There was a need for a more industrial means of killing. To that end, an experiment was carried out in September 1941 using Zyklon-B (hydro cyanide or HCN) to gas people. 600 Soviet prisoners-of-war and 250 sick Poles were the first victims. The experiment was a succes but Block 11 turned out not to be suitable as a gas chamber: it took days to ventilate the room. For that reason, gassing was continued in the largest room of the crematorium which was equipped with a better ventilation system. As soon as the two gas chambers in the second camp of Auschwitz, Birkenau, became available, the number of gassings in Auschwitz I gradually diminished.

Despite the number of people that were killed during the first months of operation, a few hundred prisoners were released. Why they in particular were selected was not always clear, although international pressure, from the Red Cross for instance, certainly played a role.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Zyklon-B

- Poison gas that was systematically used in German extermination camps, primarily to murder Jews.

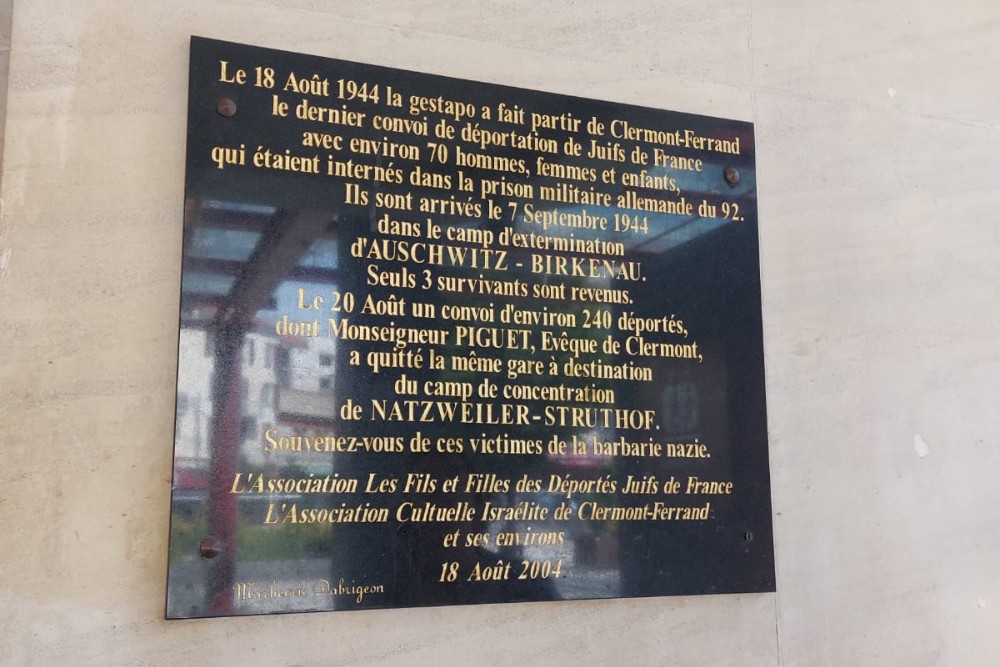

Images

The well known entrance gate of Auschwitz I (1945) Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The well known entrance gate of Auschwitz I (1945) Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Block 10 housing the prison Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Block 10 housing the prison Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. In Block 11 the first gassings took place Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In Block 11 the first gassings took place Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.The final solution

IG Farben

At the end of 1940, it became clear that the war was far from over. Great Britain had not been captured and she refused to take sides with Germany. In this situation, the chemical concern IG Farben acknowledged the necessity of concentrating on the production of synthetic rubber and gasoline. The Third Reich suffered from a lack of raw materials and those products should compensate that. To that end, Otto Ambros, executive manager of IG Farben started looking for a suitable place in the east to build a factory. A production process like that needed lime, water and coal. Moreover there would have to be a good transportation network and sufficient manpower. Ambros found what he looked for in the vicinity of Auschwitz. Yet, the presence of the camp was not immediately considered a labor pool. Ambros counted more on ethnic Germans as laborers.

Yet, the establishment of the IG Farben plant was important to Auschwitz. Heinrich Himmler visited the camp in 1941. He ordered to raise the population from 10,000 to 30,000. They were to help constructing the new plant. All this fitted into a larger frame: Himmler had grand plans with Auschwitz and its vicinity. Plans were drafted for a new German city where some 40.000 Germans could be housed.

Höss also saw the advantages of the establishment of the IG Farben plant. Up till then, the camp commander had been faced with a chronic shortage of materials to achieve the expansion of the camp. Höss suggested that when IG Farben "assisted to speed up the expansion of the camp, it would be in the interest of the company as sufficient laborers could be deployed that way." During a meeting on March 27, 1941, IG Farben and Höss agreed on the payment for the labor and workers provided. The company was to pay 3 Reichsmark per day for an unskilled worker and 4 Reichsmark for a skilled one. An agreement was also reached about the price IG Farben was to pay for every cubic yard of gravel, the prisoners would dig out of the river Sola.

The Endlösung

The impressive plans of Himmler and IG Farben regarding Auschwitz were overshadowed by the ‘final solution of the Jewish problem.’ During a meeting with Himmler in Berlin, Höss was informed of Adolf Hitler’s plans concerning the Jews: "The Jews are the eternal enemy of the German population and must be exterminated. All Jews living within our reach must be eliminated without exception during the war." Because of its favorable location Himmler had selected Auschwitz to be part of those plans. Höss was to receive more detailed instructions later.

Meanwhile Höss had to establish a completely new camp. Himmler wanted to use this camp for the final solution of the Jewish problem Hitler had ordered him to solve. One of Himmler’s most important instruments of the Holocaust, Adolf Eichmann was to inform Höss about the further details about the execution of this task soon but it had become clear to Höss in the meantime that the final solution was intended to eradicate the entire Jewish population. This process had already begun on a smaller scale in the various concentration camps and by the Einsatzgruppen which carried out mass executions of Jews and other ‘enemies of the state’ in the areas occupied by Germany.

On January 20, 1942, the Wannsee Conference was held in Berlin. Various high ranking Nazi officials and SS men discussed the logistics and practical execution of the Endlösung. The conference was chaired by Reinhard Heydrich while Eichmann wrote the minutes. He would ultimately be responsible for the death trains. On March 26, the first transport organized by Eichmann arrived in Auschwitz. It consisted of many Slovak Jewish women, they were housed in the barracks in which Soviet prisoners-of-war had been locked up previously. Even more, these first women in Auschwitz were even forced to wear the uniforms of the murdered Soviets.

Definitielijst

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Images

Auschwitz II and Auschwitz III

Auschwitz II: Birkenau

Despite the first – provisional - gas chambers and larger ovens, the capacity was not sufficient for the Nazis. Auschwitz had to be expanded, certainly as it was to play an important role in the Endlösung now. In September 1941, plans were drafted and a short time later construction of a new camp was started near Brezezinka (Birkenau). That village had already been evacuated in July 1941 and its inhabitants transferred elsewhere.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Bischoff and architect Fritz Ertl were responsible for designing and building the new camp. The plans made it very clear no one was to leave the camp alive. Initially, each shed would house 550 inmates; about one third of the space provided in the average concentration camp. Obviously, this was not sufficient because in a hand written adaptation, the number of Häftlinge (prisoners) per shed was raised to 744. As many people as possible were to be packed together in as little space as possible.

Camp Birkenau or Auschwitz II was built by the inmates themselves. To that end, 10,000 Soviet prisoners-of-war were transported to Auschwitz; within less than a year hardly a few hundred of them had survived. The Soviets were the first inmates to have their prison number tattoed, this was done to make identification of the dead easier. The first tattoos were not placed on the am but punctured in the chest with long needles and subsequently ink was rubbed into the punctures. After the Soviets had torn down the houses in the village, construction of the camp itself was started.

Just outside the new camp grounds, an area of some 0.76 square miles with over 300 sheds, stood two beautiful farm houses, surrounded by fruit trees and hedges. Bunker I and II as they were called, were ready for use at the end of June 1941. On the doors, signs with the text ‘to disinfection’ and ‘wash room’. This way, the Jews were misled until the last. New prisoners were split in two groups right after arrival: those fit enough to work and those who were not. The ‘unproductive‘ Jews were gassed as soon as possible. The guards convinced them that entering these buildings was part of the procedure. Disinfection and washing was necessary to prevent epidemics from breaking out in the camp. The prisoners had to undress and subsequently entered the building. Zyklon-B pellets were then dropped into the room through chutes in the roof. Shortly afterwards, the gassing was over. This method of murdering offered quite a few advantages: it happened quickly and massively, the prisoners entered the so-called disinfection and wash rooms quietly by themselves and the whole process was less strenuous for the guards. The real systematic selections of prisoners were made from July 1942 onwards. The selections were made by the camp physicians.

A major difference between Auschwitz I and Birkenau was that the gas chambers in Birkenau were actually situated outside the camp. That way, daily life in the camp was not disturbed. The gas chamber annex crematorium in Auschwitz I was situated in the middle of the camp. In order to drown the yelling, two engines were used, running stationary. The sound emanating from the gas chamber was never entirely drowned though, consequently the murdering could not be kept hidden from other inmates. This also was one of the reasons why the gassings in Auschwitz were gradually scaled down as soon as the gas chambers in Birkenau became operational.

Thanks to the new gas chambers, the number of gassings increased sharply; confronting the SS with a new problem: crematorium I could not keep up with the number of corpses. For that reason, the corpses were initially dumped into mass graves which did not remain without consequences. Owners of nearby fish farms complained about the high death rate in their ponds. Investigation showed that the many decaying corpses polluted the groundwater to such an extent that the fish died. In order to solve this problem, from September 1942 onwards, gassed prisoners were burned in large open pits, causing an enormously foul stench which could be smelled miles away. It was obvious this could only be a temporary solution.

On September 30, 1942, Höss was rewarded for his ""work" and promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer. Auschwitz II meanwhile had been completely converted to an extermination camp. In order to speed up the processing of the corpses, yet more crematoriums were built. Between March 22 and July 25, 1943, crematoriums II, III and IV entered service. Gas chambers were simultaneously constructed in these new buildings so the murdering could proceed even more efficiently. Thanks to the new gas chambers, it was no longer necessary to use the converted farm houses (Bunker I and II).

The Nazis found ever more efficient methods to burn the corpses. Together with the technicians of Topf & Söhne, the firm which had constructed the ovens, they discovered the ‘Express method,’ enabling them to cremate three corpses in one oven. Moreover they discovered that the cremation proceeded quicker when one of the corpses was better conserved. Such a corpse contained more fat, which improved the burning process and so saved fuel.

Auschwitz III: Monowitz

In total, Auschwitz numbered some 40 satellite camps where inmates were deployed as slaves. The largest camp was Buna (Monowitz) at 3.7 miles from Auschwitz 1, holding some 10,000 laborers. The best known inmates were Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi. The adjacent factory, built by Auschwitz prisoners for IG Farben produced synthetic rubber and gasoline and was operational from 1942 onwards. Yet this plant did not produce anything during those years. From November 1943 onwards, Monowitz was an official separate administration and so became Auschwitz III.

Out of the tens of thousands inmates working there, a large number died from the hard labor, serious torturing and hunger. Yet, the people working here had a better chance of survival, simply because they still were able to work. Those who could not keep up with the pace or fell ill ended up in the gas chambers without mercy. To weed out the weak, selections were frequently made. As mentioned before, the chemical concern IG Farben – which invested more than 700 million Reichsmark in the plant – was located here along with a cement factory, a coal mine, a shoe factory and a weapons factory. Quite a few Auschwitz prisoners were deployed on enormous farms, including Rasjko’s, where agricultural experiments were carried out.

The camp remained operational until one week before it was liberated by the Soviets. At that time, inmates who could still walk were evacuated to other camps closer to Germany. The sick and the weak were left behind.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- Zyklon-B

- Poison gas that was systematically used in German extermination camps, primarily to murder Jews.

Images

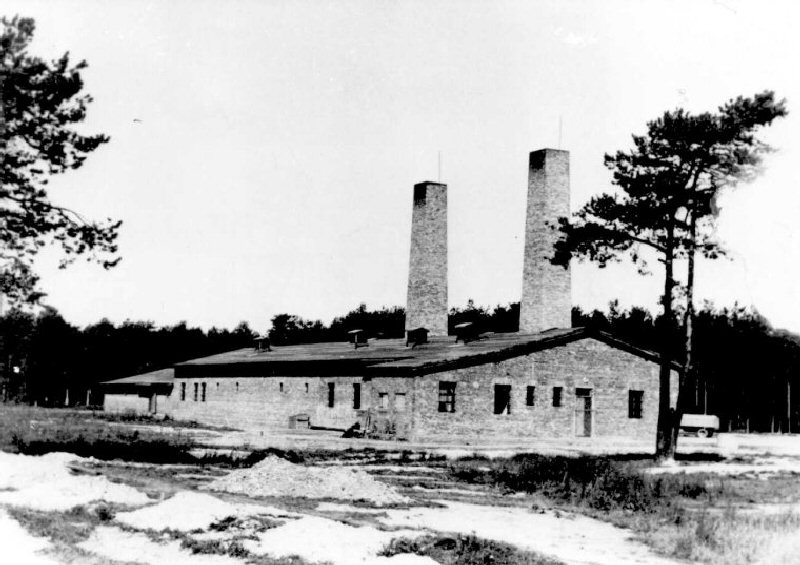

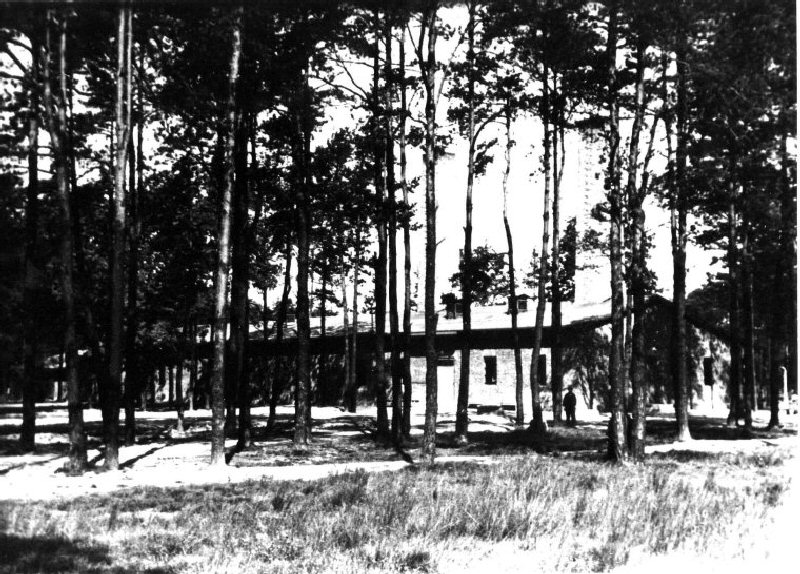

Gas chamber and crematorium III Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Gas chamber and crematorium III Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Gas chamber and crematorium IV Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Gas chamber and crematorium IV Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Gas chamber and crematorium V Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

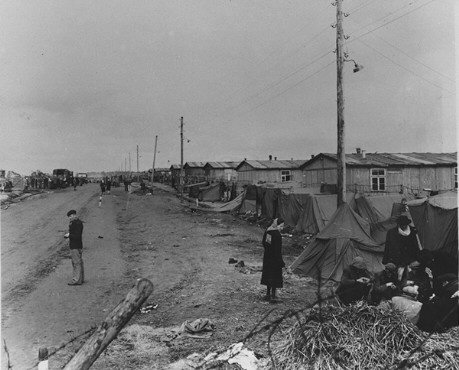

Gas chamber and crematorium V Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Monowitz: the third part of Auschwitz Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Monowitz: the third part of Auschwitz Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.Daily life

Prisoners arrived in their thousands in the freight yard in Oswiecim. Later on, the Nazis used a purpose built platform in Birkenau. All had made a miserable and long journey – often more than 1243 miles - under their belts in freight cars. Without food, without water, without toilets or heating and in overcrowded cars: for the weakest – the elderly, babies – the journey itself was fatal. In almost all cars, quite a few corpses were left behind.

The journey took forever but once they arrived everything had to be done in a hurry. Everybody was continuously chased by the SS men. They kicked and beat them whenever the prisoners did not move fast enough. The Jews, overwhelmed and dazed by the misery of the journey, followed orders without protest. Then the first selection was made. Women and men were separated; there was no time to say goodbye. Those considered fit for labor were sent to the right, the others to the left. The second group, consisting of women, children and the elderly went straight to their death. No protest arose as most of them did not know what was awaiting them. The guards lied to the unsuspecting arrivals that the separation of families was only temporary. This strategy to calm them down was a conscious policy of the guards: that way the trips to the gas chambers and the gassings themselves proceeded much more efficiently. The presence of the Sonderkommando, of which Jews were in charge, also helped to put the frightened people at ease. "They saw Jews who were alive and thought they would stay alive themselves as well."

Once the gassings were over, the Sonderkommando went to work. Their task consisted of taking the dead out of the gas chambers to the crematoriums. After the possessions of the dead had been sorted, the corpses themselves were looted. Gold teeth were extracted, the hair of the women was cut. German factories made that into cable strands, industrial felt or yarn while the gold teeth were melted down to bars. The human ashes were used as fertilizer or dumped into neighboring ditches and ponds.

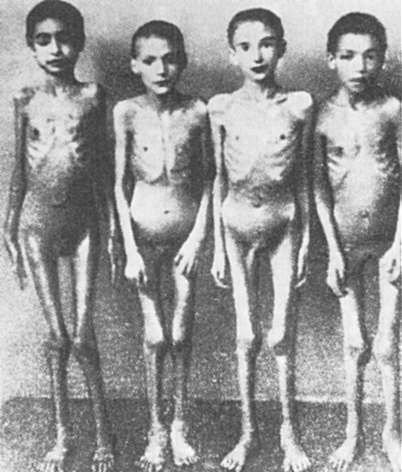

Those who were not gassed had a number in blue ink tattoed on their lower arm. Henceforth, they had a number, no name. Subsequently, the prisoners went to the ‘sauna’ were they were shaved and disinfected. The guards were frightened to death to be infected with spotted typhoid themselves which was transferred by lice. That is why they frequently carried out massive disinfections and delousing actions. Nonetheless the camp swarmed with lice and rats. Finally, everybody stood in line for clothing: coarse striped prisoners’ garb – no more than a thin shirt, an equally thin pair of trousers and a cap – which offered no protection whatsoever against the cold. In the course of the war, normal clothing was issued instead of the striped uniforms in order to cut expenses. The newbies spent the first few weeks in quarantaine where they had to do sports and tough exercises all day long. They were continuously stirred up by new orders and tasks. Those unable to keep up were mercilessly beaten up or shot.

Those inmates who were spared – temporarily – and put to work, were to hand over their possessions. All those belongings ended up in a large wharehouse, called Canada by the inmates as probably Canada was something like the promised land where everything was present in abundance. In any case, all the goods were sorted here and shipped to Germany for use by the SS, the Wehrmacht and the civilian population. Those inmates working in Canada often managed to steal things which they could exchange for food stuffs. Whoever was allowed to work in Canada had a far better chance of survival. They usually worked inside which was a considerable advantage during the harsh Polish winter. Moreover, they had more to eat than other prisoners as they often discovered food among the belongings. The guards also made themselves guilty of theft and enriched themselves. Camp commander Höss knew his "SS men were not always strong enough to resist the temptation of all those valuables." Supervison of the guards was poor and remained poor.

Each morning began in the same way. After a short and often bad night’s rest, roll call was held. When the bell sounded, prisoners lined up in rows of five in front of their barracks. The dead were taken out too and then the counting started. Things always went wrong however, someone was always missing. As long as the missing person was not found, his fellow occupants had to wait, regardless of the weather conditions. The waiting could well take hours. Following roll call, "breakfast" was served and then the signal was given to go to work. They marched to their work in long columns, sometimes miles away from the camp. As they marched out through the gate, they were accompanied by music played by an orchestra made up of prisoners.

The work was very diverse: people were put to work in gravel and stone quarries, on farms, in armaments factories and coal mines; others helped build new factories and work shops. Around noon, the workers received about 34 fl. ounce of soup to eat. The soup was no more than filthy water with some potato or beet skins. At night, after a long day of hard work, they returned to the camp. Each day the survivors dragged the dead along with them, after all another roll call, sometimes lasting for hours, would be held at which the prisoners were counted once more. One particular roll call on June 6, 1940 lasted 19 hours. The direction of the camp often held roll calls as punishment at which prisoners had to endure the count squatting or kneeling. During roll call, prisoners who had stolen or had been caught attempting to escape were regularly hanged. Finally it was supper time: 10.5 ounces of bread with very seldom a little margarine or a sausage. The daily food rations contained between 1,300 and 1,700 calories, far too little for adults who had to do hard physical labor as well. Pictures taken immediately after liberation show prisoners weighing less than 66 lbs.

Not all prisoners were put to work outside the camp. As mentioned before, there were the members of the Sonderkommandos and the Canada workers. In Auschwitz itself, inmates were deployed as fire fighters. They could move about the camp in relative freedom and were able to "organize" – as stealing was called in the camp – quite a lot. In this connection, the alleged swimming pool of Auschwitz must be mentioned. Its presence was and still is a reason for revisionists to doubt the existence of the extermination camp. The so-called swimming pool actually served as a water reservoir but the fire fighters had constructed some kind of diving board and sometimes, swimming actually took place in there. There was also a bordello in Auschwitz. It was one of Höss’ last initiatives as he would be side tracked at the end of 1943. In Block 24 in Auschwitz I he had a bordello established. It had been Himmler’s idea who thought to raise productivity that way. A visit to the bordello was to stimulate the inmates to work harder still. Of course, not everybody was allowed to enjoy this "service." Jews, considered one of the lowest categories of inmates, were refused entrance. Mainly political prisoners who had been locked up in the camp for years and had gotten themselves privileged positions were allowed to use the bordello as a reward for their cooperation. Once again, this was another example of the divide and rule policy of Höss.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Selection of the freshly arrived prisoners took place right on the platform Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Selection of the freshly arrived prisoners took place right on the platform Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. A Sonderkommando at work Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

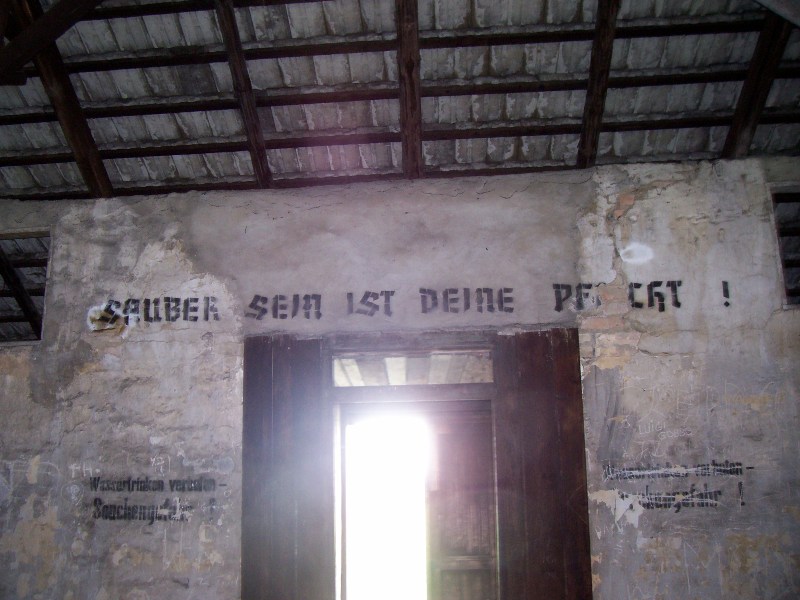

A Sonderkommando at work Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Text in a barracks in Birkenau: to be clean is your duty. Beneath the contradictory message: "the water is undrinkable for danger of fungi" Source: Paul Boellaard.

Text in a barracks in Birkenau: to be clean is your duty. Beneath the contradictory message: "the water is undrinkable for danger of fungi" Source: Paul Boellaard. Inmates at work Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Inmates at work Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.The experiments

In each extermination camp, physicians were involved in the extermination process. Here, an important question arises: how can someone, who has sworn the oath of Hippocrates which obliges physicians to heal the sick, cooperate with such mass murders? SS physician Fritz Klein was confronted with this question. His response was: "As I have sworn the oath of Hippocrates, I remove an appendix from a human body. The Jews are the festering appendix in the body of humanity. That is why they have to be taken out." It was obvious that the Nazis – and hence the physicians working with them – started from the principle that certain races were inferior and so less Lebenswert (worth living) than others. Quite a lot of physicians cooperated with the selection policy of the Nazis from the beginning. Initially they cooperated in the sterilization and euthanasia programs; later they worked in the camps. It was therefore no coincidence that a physician, Dr. Eberl, was named camp commander of Treblinka.

According to Nazi logic, extermination camps were part of health care. People like the Jews, who were considered a threat to the well being of society had to be eliminated from that society. It was no coincidence that the first murders in Auschwitz were carried out in the hospital. Whoever was admitted with dysentery or typhoid did not have to reckon with being cured. Only very rarely someone managed to leave Block 10, the sick bay, alive. Drugs, bandages or disinfectants were not provided. Most of them were just given a lethal injection with phenol.

Physicians played an important role in all fields in the extermination camps. First of all, they were involved in the selection of the incoming prisoners. This for two reasons. They were considered the best to judge whether or not someone was fit for labor. Secondly, that way the Nazis wanted to make the impression that gassing was not carried out but was based on a scientific task, to make and keep the Nazi society healthy.

The physicians in Auschwitz became notorious for their medical experiments. Joseph Mengele, the Angel of Death or Doctor Death, became the most notorious for his experiments with twins. He wanted to understand the role of traits inheritance in the development and behavior of people. The twins were compared in every detail. Each day, Mengele drew blood from them that was sent to Berlin for research. After the blood had been investigated and processed, it was sent back to Auschwitz where the blood from one half of the twin was injected into the other, often resulting in the twins suffering from head aches, fever and other diseases. In order to investigate whether the eye color could be changed, Mengele injected a coloring agent directly into the eye. This very painful treatment always resulted in inflammation of the eye and often in blindness. Young twins were subjected to the most gruesome experiments during which limbs were amputated and organs removed – without any sedation whatsoever. Other twins were injected with bacteria causing all sorts of diseases so Mengele was able to record how long it would take them to die. It did not matter that they would not survive those experiments. There were enough guinea pigs available anyway and moreover, he could perform autopsy on their bodies. He considered this a unique opportunity because where can one find, under normal circumstances, twins who had died in the same place at the same time?

Joseph Mengele may well be the man whose name is inexorably connected to Auschwitz; the experiments of others physicians in the camp were hardly less gruesome. Gynaecologists Carl Clauberg and Horst Schumann carried out "medical research" in the field of sterilization. This was considered one of the possible solutions of the Jewish problem. By administering injections with chemicals or exposure to high doses of X-rays the doctors could render the Jews infertile without the victims losing their productivity. Finally, there was chief physician Wirths. He investigated the physiology of the cervix. In all these experiments women in particular were the victims. Yet medical experiments were carried out on men as well. The physician rubbed the skins of the prisoners with a series of toxic substances intended to find out what kind of tricks possibly were used by simulators wanting to dodge compulsory military service.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

Aktion Höss

Up to 1944, Hungary, ruled by her regent Miklos Horthy was a loyal ally of the Third Reich. When in 1943, the fortunes of war seemed to shift, Horthy turned to the Allies. This was very much to Hitler’s dislike who invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944 and established a puppet government in Budapest headed by Premier Dome Sztojay. Horthy however retained his function as head of state. Up to then, Horthy had persecuted the Jews but never extradited them. That changed under Sztojay who had the Jews herded together in ghettoes and transit camps awaiting their deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The first two transport left Kistarcsa – 1,800 Jews – on April 29, 1944 and Topolya (2,000 Jews) on April 30. But the main task was yet to begin as some 750,000 Jews were living in Hungary.

For this enormous undertaking, a man with vast organizational experience had to be found. In the summer of 1944 Rudolph Höss was sent to Auschwitz again, charged with the task to make the extermination of the Hungarian Jews possible. The operation was given the name Aktion Höss. He prepared the camp meticulously. The crematoriums were renovated, the ovens were covered in flame proof stones and the chimneys re-inforced with iron rings. Behind the crematoriums, deep pits were dug and the number of Sonderkommandos was increased drastically. On May 15, 1944, after an interruption of two weeks, the most important phase of Aktion Höss was launched. From mid May onwards, 12,000 Jews left for Auschwitz every day to be murdered in the gas chambers straight away. In a period of hardly 56 days, until July 9, 1944, over 400,000 Jews were transported from Hungary to Auschwitz to be gassed.

After about four days, the Hungarian Jews arrived in Auschwitz. Just like in all other transports, the cattle cars in which they were transported were overcrowded. The people could hardly breathe and were given no food or water at all. Many, especially children and elderly and sick people died from dehydration. Because of the large number of transports and the enormous influx of people, the SS men were forced to select far less people to be sent to the gas chambers. Yet the number of gassed people was so high, the crematoriums could no longer keep pace with the vast number of corpses. Consequently the Sonderkommando burned the corpses on piles or in pits.

Under pressure from a number of neutral countries and the Vatican, Horthy once again prohibited the deportations. The Allies had threatened to hold him personally accountable for the deportations. At that moment, Germany was unable to react: she had suffered heavy losses on all fronts during the past month. Nonetheless, in August 1944 a few hundred Hungarian Jews, who had been locked up in a camp for political prisoners in Kistarcsa, were deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolph Höss had completed this task more than eminently and Berlin was very satisfied. In recognition of his impeccable service record for the Third Reich, he was awarded various decorations including the Kriegsverdienstkreuz I and II.

Definitielijst

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

- The largest German concentration camp, located in Poland. Liberated on 26 January 1945. An estimated 1,1 million people, mainly Jews, perished here mainly in the gas chambers.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

Images

Resistance

The only thing that mattered to most prisoners in Auschwitz was getting through the day as best as possible, in the hope the gruesome acts would stop one day. Yet there were people who, even in the most trying circumstances, dared make such decisions and put their own lives on the line in order to save others. The uprising in extermination camp Sobibor and in the Warsaw ghetto are among the best known resistance actions but Auschwitz had its resistance heroes as well. Little is known about these actions as the resistance fighters often did not survive.

The resistance in Auschwitz operated in different ways. There were various active cells including Polish, Czech and Communist groups. They tried to improve the spirit of the prisoners as much as possible, attempted to smuggle news and food into the camp and get their own people in important functions in the hierarchy of the camp. Contact was made with people living close to the camp. In coded messages, information on life in the camp, the guards, the crimes and the mass murders were smuggled to the outside world. Most of the SS men were later identified through those messages. Based on such information, which eventually reached the Allies, the British published a list with the names of 15 responsible officers in Auschwitz on BBC radio.

The underground movement acted in particular against the criminal kapo’s who worked with the SS in exchange for food for instance. The resistance cells, sometimes working together, attempted, within their possibilities, to relieve the prisoners who worked with the SS from their posts and replace them by political prisoners. Furthermore they also organized several illegal activities. Thus, a real propaganda campaign was started to incite the inmates to solidarity. Cultural activities with national poems were set up and there even was an underground art movement. The orchestra, that was allowed to play music openly, took part as well: it managed to play traditional Jewish music (although adapted) in order to cheer up the prisoners.

October 7, 1944 was a memorable day in the history of Auschwitz. Members of the Sonderkommando had drafted plans, together with members of the underground movement, to rise up against their guards. Through its network of kapo’s, the SS had been informed and a number of resistance fighters were murdered. Nonetheless, the prisoners did not want to abandon their plans. The Sonderkommando had increased meanwhile to 9,000 people. They knew the SS did not consider that many necessary any longer. Not being necessary any longer meant a certain death in Auschwitz. In order to evade the imminent decrease, the Sonderkommando of crematorium IV revolted. The Jews threw themselves at their guards with pick axes and stones and set fire to the crematorium. The Sonderkommando of crematorium joined the revolt and shoved one of the guards in the burning oven alive. During the uprising, 250 members of the Sonderkommando were shot. Another 200 Jews who had managed to escape or were suspected of having had knowledge about the revolt, were executed. Three SS men were killed. The rebels had paid a high price but their sacrifice was not for nothing. As a result of their revolt, crematorium V where at that moment a group of Jews was to be gassed, was evacuated.

Organized resistance in Auschwitz was and remained the work of a small group of people. Starved, dazed, disoriented and overwhelmed by the circumstances and the cruel conduct of the guards resulted in people not giving a single thought to revolt. They could not image that a revolt could result in whatever kind of success. Yet, some stories are known of individual resistance. October 23, 1943, a transport of Polish Jews arrived in Birkenau. Everyone was sent directly to the gas chambers. Most of the people were already inside when an incident occurred that was reported not only by Höss but also by the Sonderkommando. Two women, a mother and her daughter, refused to undress completely. Both kept their underwear on. When one of the guards, waving his pistol, yelled they had to undress completely, the daughter undid her bra and with it, tore the pistol out of his hands. She quickly picked up the gun and shot the guard. Other prisoners also reacted and the SS men were attacked. A fire fight ensued between the guards at the entrance of the gas chamber and the prisoners. Eventually Höss intervened. He forced his way in with his guards: all prisoners were herded together and executed one by one.

As impossible it may seem but some prisoners did manage to escape from the camp. In April 1944, Rudolph Vrba and Alfred Wetzler escaped from Auschwitz-Birkenau. They reached Slovakia where they made contact with the local Jewish community. Both men told their story but initially they were not believed. Only after endless interrogations, the other Jews began to believe them. Vrba and Wetzler wrote their story in a report that later became known as the Auschwitz protocol. In it, when, how and many Jews had been murdered in Auschwitz was described in amazing detail. This document was copied and sent to the Vatican, the Jewish leaders in Hungary and the western Allies. Without result: the Allies had known about the activities in Auschwitz for a long time but made no direct attempts to stop the mass murders. The detailed information in the Auschwitz protocol did not change their minds in any way.

Definitielijst

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

- The largest German concentration camp, located in Poland. Liberated on 26 January 1945. An estimated 1,1 million people, mainly Jews, perished here mainly in the gas chambers.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- kapo

- A Kapo was a prisoner in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany during World War 2 who was assigned to supervise other prisoners. A Kapo had to supervise the work of the prisoners and was responsible for their results on behalf of the SS.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

The camp orchestra playd (adapted) Jewish songs, while other prisoners left the camp on their way to work Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The camp orchestra playd (adapted) Jewish songs, while other prisoners left the camp on their way to work Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.The end

While the gas chambers and crematoriums in Auschwitz and the other extermination camps continued to operate at full capacity, things got gradually worse for the German war machine. Allied troops advanced relentlessly towards the borders of the Third Reich and the Red Army approached from the east and hence was the biggest threat to Auschwitz. From the close of 1944 onwards, the leadership of the camp began burning all sorts of documents, files and notes they had kept on the mass murders. The Nazis knew for some time this moment was coming and they had taken the necessary precautions. In the spring of 1944, Heinrich Himmler had issued orders to the camp commanders for the so-called Fall A, meaning that as soon as hostile armies arrived at the gates, the command was immediately transferred to the camp leadership. They did not have to wait for orders from Berlin which might never be forthcoming anyway.

Himmler knew all too well what was awaiting him and the other responsible people when the gruesome truth about the extermination camps was unveiled. In order to prevent this, all prisoners in the camps in the east were to be evacuated. In the so-called death marches, they were taken deeper into the Third Reich. This way, Himmler and his henchmen wanted to prevent witnesses from the death camps telling their stories. In August 1944, 130,000 people were still registered in Auschwitz; towards the end of the year over half of them had left the camp. Many others were silenced immediately: mainly members of the Sonderkommando as they were the most important eyewitnesses of the gassings. Meanwhile, as much material as possible was taken away: bricks, wood, cement but clothing, jewelry and other valuable items as well, all stolen from the inmates.

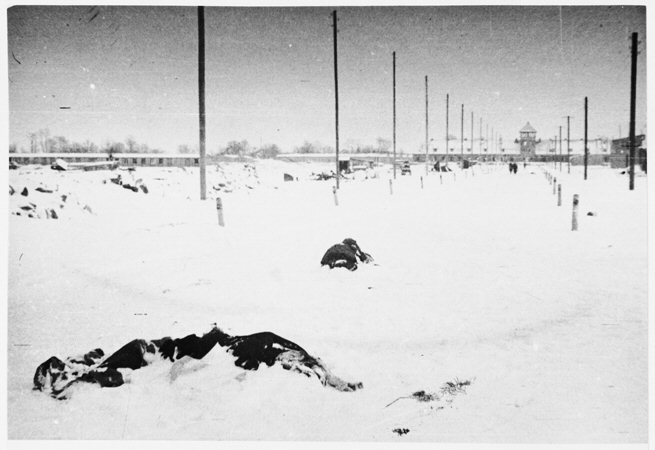

In January 1945, the Red Army came dangerously close. This was the signal for the Nazis to start the mass evacuation of Auschwitz, Groß-Rosen and Stutthof. Gas chambers and crematoriums were blown up, sheds and warehouses put to the torch. On January 18, the camp was evacuated, in other words only those who were fit enough. Some 58,000 people left Auschwitz while almost 9,000 sick were left behind. Special SS units killed hundreds of those left behind while hundreds of others died from the cold and the total lack of food and care.

On January 27, 1945, the first Soviet troops entered the camp. What they discovered borders on the unbelievable. In addition to many thousands of exhausted and sick inmates, they found more then 800,000 female clothes, nearly 35,000 male suits, 15,000 lbs of female hair, thousands of pairs of shoes, glasses etc in the warehouses.

For those who left prior to the liberation, their suffering was far from over. Most of them went to Groß-Rosen first and from there, they were marched to camps located deeper inside the Third Reich: Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Mauthausen, Flossenburg and Mittelbau-Dora. During these endless death marches thousands perished. About one quarter of the inmates who had left Auschwitz in January 1945 did not survive the journey. The conditions were harsh in the extreme for the already exhausted prisoners. It was freezing cold, their clothing offered no protection whatsoever against the wind. At night, shelter was very rare: every morning the column left many behind, frozen to death. The amount of food that was distributed was totally insufficient. Those unable to keep up were shot without mercy.

A large number of the prisoners from Auschwitz, some 20,000 were eventually housed in Bergen-Belsen. It was initially established as a camp for "privileged"Jews who were kept as hostages. From 1944 onwards, prisoners from other camps were locked up there as well. The Germans however had not taken care of required housing: the hygienic conditions defied all imagination. Dysentery, cholera, typhus further diminished the number of prisoners. The mortality was sky high, gassings and executions were not even necessary. Despite this enormous mortality rate, the British liberated some 60,000 prisoners in April 1945. After the liberation of the camp, another 14,000 former inmates perished.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Images

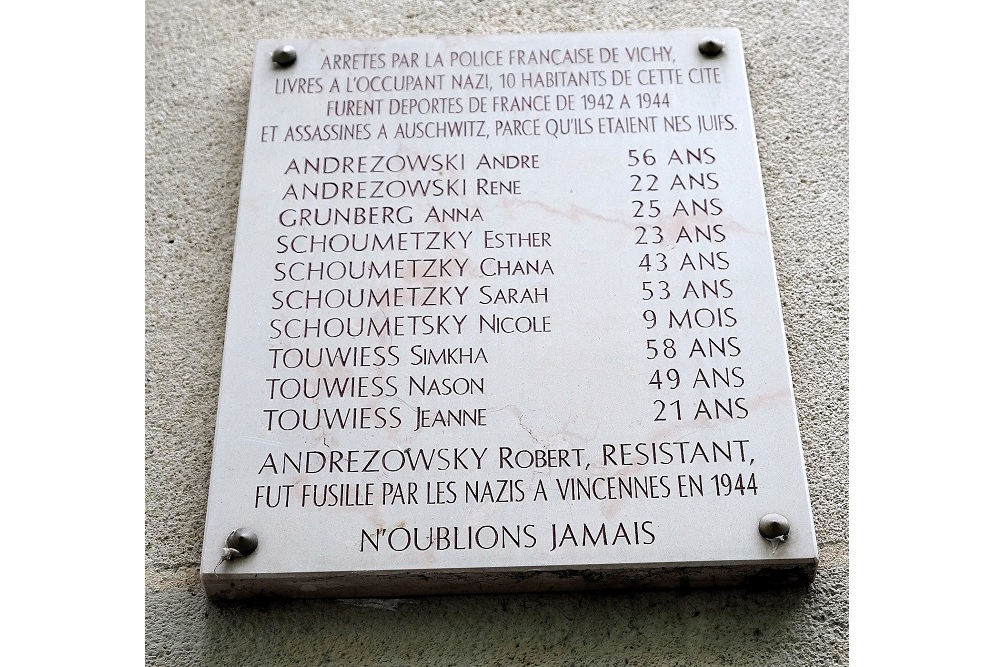

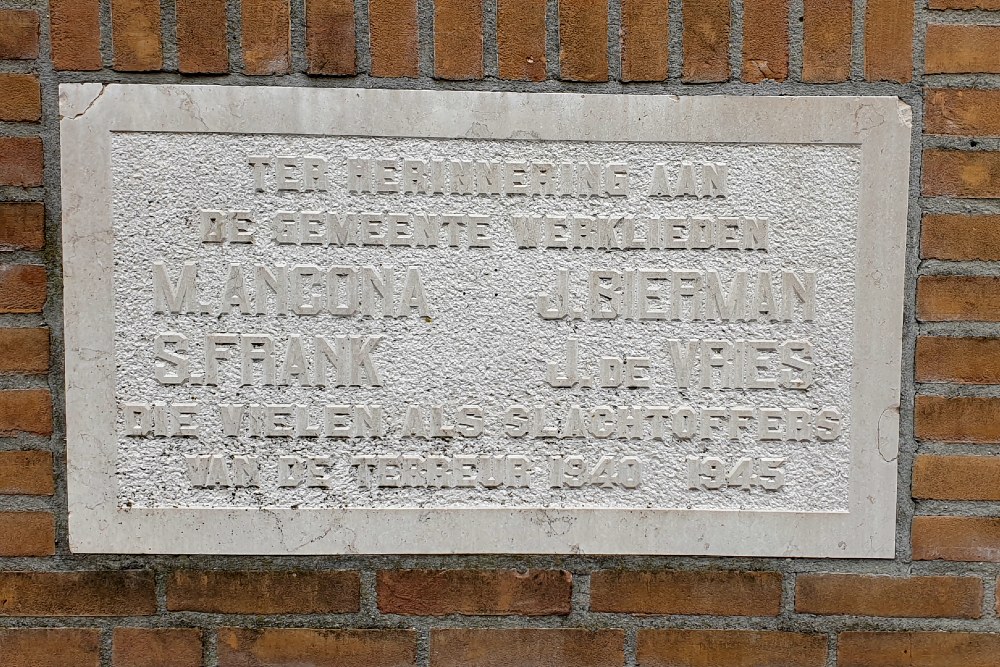

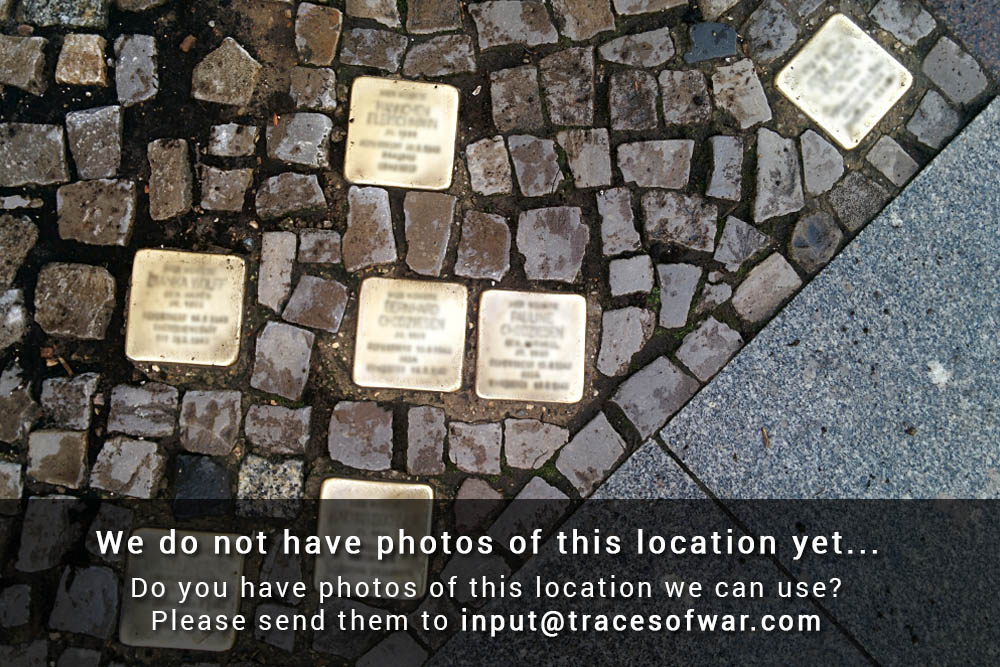

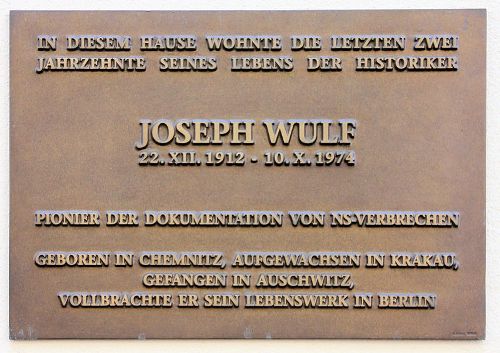

Remembrance

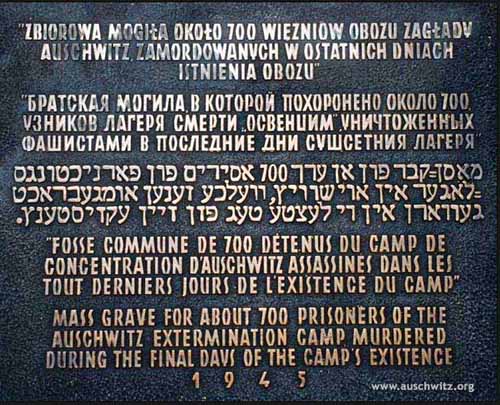

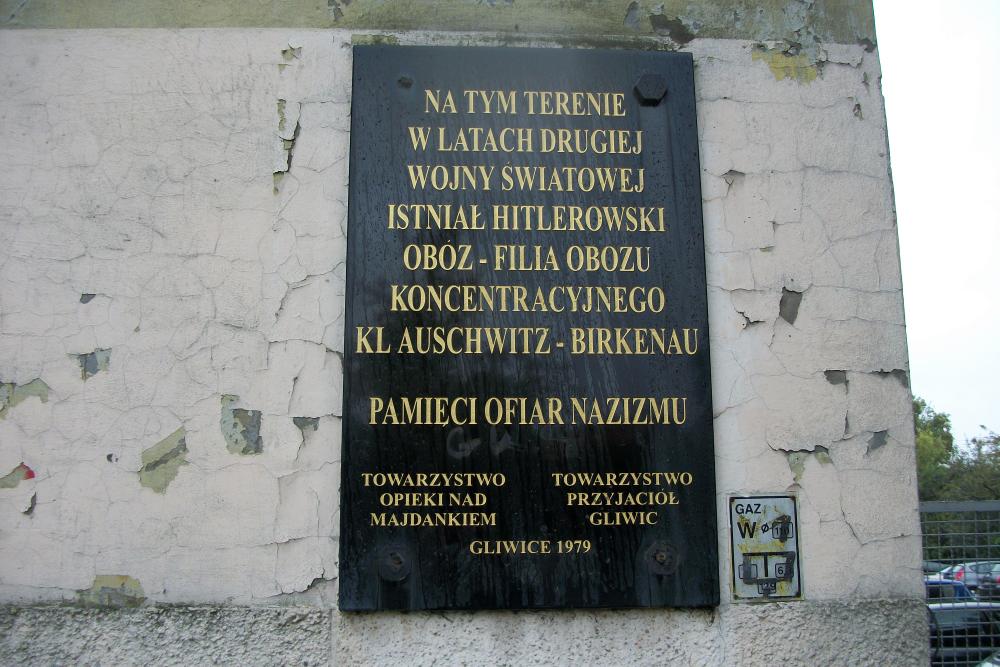

Exactly how many victims Auschwitz has claimed is hard to ascertain. The SS registered only 400,000 prisoners of which over half has died. The large majority has never been registered though. In most cases, 70 to 75% of every transport was gassed straight away and cremated. In recent publications, it is estimated that about 1,1 million Jews, 70,000 Poles, 20,000 Gypsies, 10,000 Soviet prisoners-of-war and over 10,000 prisoners of other nationalities have perished; a total of over 1,2 million.

All prisoners, without exception, are being commemorated and honored on the memorial site that former concentration camp Auschwitz is today. In 1947, the Polish government decided to establish a memorial center and a museum in the base camp. The camp complex was in serious disrepair at the time. Many people from the vicinity tore down the barracks as they could use the wood for their own houses. After the decision of the Polish government, little changed. It took years before the grounds of Auschwitz and Birkenau were being maintained and cared for in a proper manner.

In 1967, an international monument for the victims was unveiled while in the following years, the nations which had lost country men in Auschwitz were given the opportunity to establish a national pavilion in one of the former barracks. In 1979, UNESCO declared concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau a world heritage site. A number of barracks can be seen in the condition in which they were discovered in 1945; in other barracks, large show-windows can be found containing objects that were left behind prior to the liberation.

Definitielijst

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

- The largest German concentration camp, located in Poland. Liberated on 26 January 1945. An estimated 1,1 million people, mainly Jews, perished here mainly in the gas chambers.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

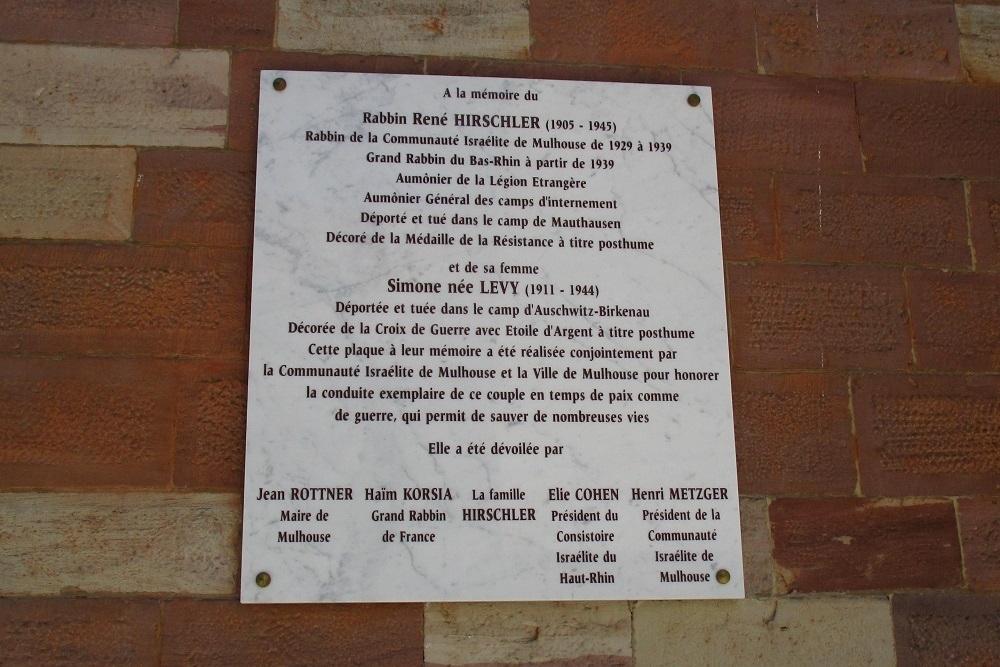

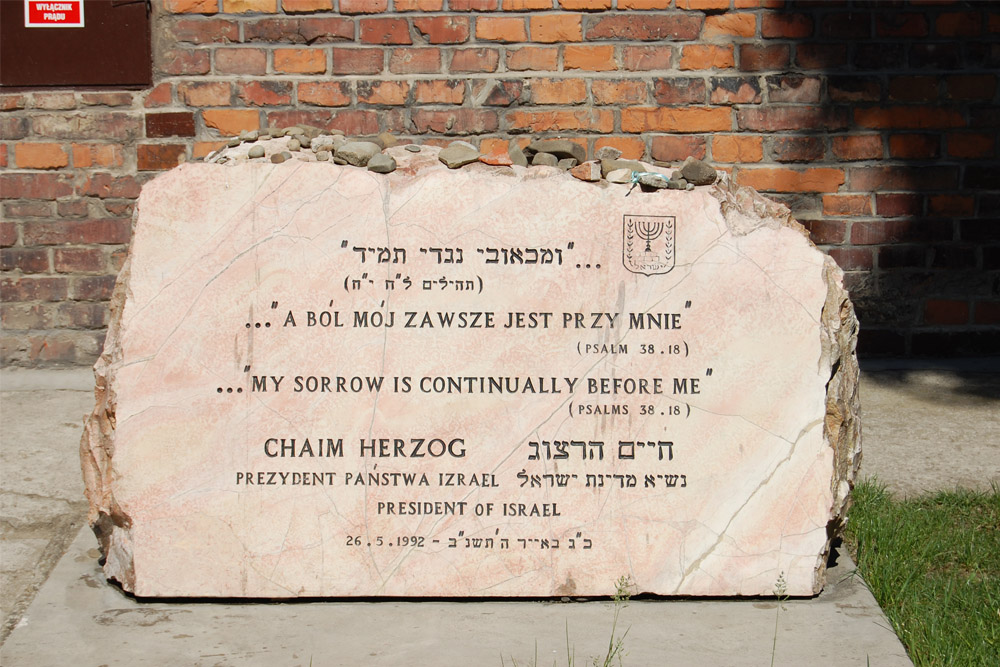

Images

The memorial monument in Auschwitz-Birkenau Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The memorial monument in Auschwitz-Birkenau Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau.Information

- Article by:

- Gerd Van der Auwera

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 07-09-2017

- Last edit on:

- 10-04-2021

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- ECK, L. VAN, Het boek der kampen, Kritak, Leuven, 1978.

- KNOPP, G., Hitlers Holocaust, Byblos, Amsterdam, 2001.

- REES, L., Auschwitz, Anthos, Amsterdam, 2005.

- FENELON, F. The Musicians of Auschwitz. London, 1977.

- KATZENSTEIN, P., VAN LAKERVELD, C., VAN THIJN, C., DA SILVA, T. Auschwitz. Nederlands Auschwitz Comité, Amsterdam, 1997.

- SMOLEN,K. Auschwitz-Birkenau Informatiegids. Oświęcim, 2003.

- Hitlers Derde Rijk. Nationale Handels Onderneming (NHA), Panningen, 2002-2003.

- Verzet in Auschwitz.

- officiële site Auschwitz.

- Rudolf Höss.

- Josef Mengele.